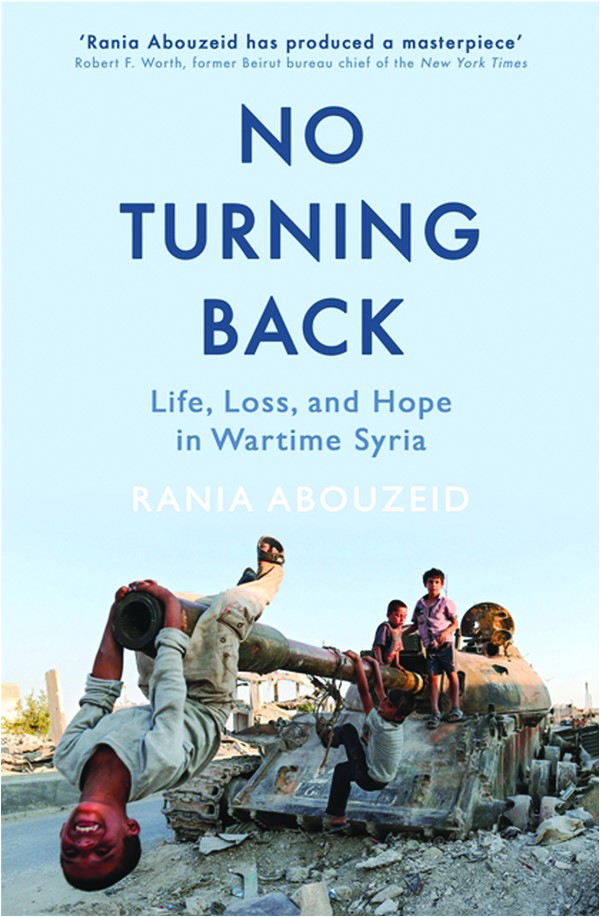

Most books deal with contemporary wars through the geopolitical lens and the interests they serve for major powers, pushing the people who bear the brunt of these conflicts to the peripheries. In a rare departure from tradition, Rania Abouzeid’s No Turning Back: Life, Loss and Hope in Wartime Syria makes emphasizes the people the focal point of the conflict. This book charts the trajectory of the war in Syria through the lives of more than a dozen characters, including children, social activists and militant rebels. No Turning Back covers Syria from 2011, when the first signs of discontent surfaced, to 2016, when the situation in Syria had metastasized into a brutal civil war. This account is a result of first-hand on-the-ground reporting over a period of six years.

Not unlike the book The Chronicle of A Death Foretold by Garcia Marquez, which beautifully captures the different interpretations of various witnesses to a murder, Rania Abouzeid’s account attempts to understand the Syrian civil war through the eyes of people whose lives have been ravaged by conflict, death, gore, devastation of social and familial bonds and displacement. There is Ruha and her extended family, cowering in the basement of their house as aerial strikes rain death and destruction. There is Suleiman, with his lacerated body languishing in a dungeon whose impenetrable and dark walls contain secrets of scores of anguished souls. There is Abu Azzam, a writer and a poet, thrust into a militant organisation that seeks to topple the government. Then, there are ‘legions of lost souls’ (Robert Fisk’s phrase for ISIS militants) that prey on chaos and instability and see Syria as a springboard for an impending Armageddon. They did not name their political organ Dabiq for no reason.

As you read the book, an important point is driven home that all the only thing missing in her narrative is the account of people who support the government and are living under in areas under its control or in areas besieged by rebel forces. The only exception is the story of Talal and his three daughters, but their story does not take up 10 pages in this 360-page tome. This omission can possibly be attributed to the fact that she was black-listed by the Syrian government in 2011, forcing her to focus on rebel forces in ‘liberated areas.’ Or it may be that her journalistic work was driven by an impulse to focus on victims bearing the brunt of war or disproportionately affected by it.

But what explains her seemingly deliberate fudging of death figures of a massacre that took place in Alawite villages, when a coalition of close to half a dozen militant groups launched pre-dawn raid? The attack took place in August 2013. Human Rights Watch went on the ground and conducted an in-depth investigation, the findings of which are markedly different from what is presented in the book. This is what Rania writes about this incident in her book: “The muhajireen waited with the Syrian fighters - including Mohammad and Jabhat al-Nusra - in Salma and Doree, facing sleepy Alawite villages, until August, 2013, when in a pre-dawn raid, they seized eleven Alawite villages-and 106 women and children.” This is how the author describes the fate of women and children hostages: “The doctor from the rebel field clinic in Salma, Rami Habib, and the his nurses regularly checked on the women and children, supplying them with fresh vegetables, meat, rice, clothes, female sanitary products, and medical attention as required. The Alawite women were given utensils to cook for themselves and the children.”

Now compare the above account with this excerpt from HRW’s report titled You Can Still See Their Blood: “Human Rights Watch has collected the names of 190 civilians who were killed by opposition forces in their offensive on the villages, including 57 women and at least 18 children and 14 elderly men .The evidence collected strongly suggests they were killed on the first day of the operation, August 4. We identified these individuals as civilians through interviews, video and photographic evidence, or a review of hospital records. Given that many residents remain missing, and opposition fighters buried many bodies in mass graves, the total number of dead is likely higher.”

Does this put a question mark on the accounts of all the people mentioned in this book? Not really. Anyone who has carefully followed the Syrian conflict over the years must have read stories of human tragedy, much like the ones recorded in this book. The experiences, grisly and macabre to the point of incredulity, are not unique in the Syrian civil war context. Moreover, the organisation, whose findings make us question her account of a significant incident, has also come up with countless briefings and reports that substantiate her other stories: the agony of living in an area under constant aerial strikes; the dismal state of prisoners in government’s cells, et al.

Does this compromise the credibility of this book as an honest and impartial account of a civil war? This book does not claim to be an unbiased account of the war in Syria, and it is not. It just records the voices of people stuck in a brutal civil war. Her cast of characters, almost all from the rebel forces, and the way she deals with the incidence of massacre in Alawite villages, rightly prompt scepticism, but war reporting in Syria has been difficult, tinged with political biases and often times it has relied on information not independently verifiable, that hardly captures the complexity of the issue, and on pictures that evoke indignation but yield little political insight.

The Syrian conflict is a complex phenomenon, and demands appreciation of its multifarious factors that make it a particularly brutal and long-lasting war. The Syrian conflict is an insurrection against the government, sectarian tussle, fight for regional hegemony and major powers rivalry wrapped into one.

One of the most beautiful things about this book is how it beautifully captures the resilience of people in the face of adversity and how it demonstrates their sense of humour. “Do you know the joke about the genie in the lamp?” one of Mariam’s nieces asked. “A man found a lamp, rubbed it and summoned its genie. ‘Your wish is my command,’ the genie told the man. ‘Great,’ the man said. ‘I need a bottle of cooking gas.’ The next day, the man rubbed the lamp again, summoning an irate genie. ‘What do you want?’ the genie asked. ‘I have run out of diesel,’ the man said. ‘Could not you have waited a few days?’ the genie replied. ‘Now I have lost my spot in the queue for the cooking gas.” There are moments that show human capacity to salvage the best of humanity in the worst of circumstances. After having been stripped of his dignity in prison, this is what Suleiman wrote in his cell, “I’ll leave, I’ll leave, but before that I will give a rose to everyone who mistreated me. I will pardon all who hurt me.” May be such thoughts are the only hope in a country torn by civil war and sectarianism.

The author is a researcher at Islamabad Policy Research Institute

Not unlike the book The Chronicle of A Death Foretold by Garcia Marquez, which beautifully captures the different interpretations of various witnesses to a murder, Rania Abouzeid’s account attempts to understand the Syrian civil war through the eyes of people whose lives have been ravaged by conflict, death, gore, devastation of social and familial bonds and displacement. There is Ruha and her extended family, cowering in the basement of their house as aerial strikes rain death and destruction. There is Suleiman, with his lacerated body languishing in a dungeon whose impenetrable and dark walls contain secrets of scores of anguished souls. There is Abu Azzam, a writer and a poet, thrust into a militant organisation that seeks to topple the government. Then, there are ‘legions of lost souls’ (Robert Fisk’s phrase for ISIS militants) that prey on chaos and instability and see Syria as a springboard for an impending Armageddon. They did not name their political organ Dabiq for no reason.

As you read the book, an important point is driven home that all the only thing missing in her narrative is the account of people who support the government and are living under in areas under its control or in areas besieged by rebel forces. The only exception is the story of Talal and his three daughters, but their story does not take up 10 pages in this 360-page tome. This omission can possibly be attributed to the fact that she was black-listed by the Syrian government in 2011, forcing her to focus on rebel forces in ‘liberated areas.’ Or it may be that her journalistic work was driven by an impulse to focus on victims bearing the brunt of war or disproportionately affected by it.

But what explains her seemingly deliberate fudging of death figures of a massacre that took place in Alawite villages, when a coalition of close to half a dozen militant groups launched pre-dawn raid? The attack took place in August 2013. Human Rights Watch went on the ground and conducted an in-depth investigation, the findings of which are markedly different from what is presented in the book. This is what Rania writes about this incident in her book: “The muhajireen waited with the Syrian fighters - including Mohammad and Jabhat al-Nusra - in Salma and Doree, facing sleepy Alawite villages, until August, 2013, when in a pre-dawn raid, they seized eleven Alawite villages-and 106 women and children.” This is how the author describes the fate of women and children hostages: “The doctor from the rebel field clinic in Salma, Rami Habib, and the his nurses regularly checked on the women and children, supplying them with fresh vegetables, meat, rice, clothes, female sanitary products, and medical attention as required. The Alawite women were given utensils to cook for themselves and the children.”

Now compare the above account with this excerpt from HRW’s report titled You Can Still See Their Blood: “Human Rights Watch has collected the names of 190 civilians who were killed by opposition forces in their offensive on the villages, including 57 women and at least 18 children and 14 elderly men .The evidence collected strongly suggests they were killed on the first day of the operation, August 4. We identified these individuals as civilians through interviews, video and photographic evidence, or a review of hospital records. Given that many residents remain missing, and opposition fighters buried many bodies in mass graves, the total number of dead is likely higher.”

Does this put a question mark on the accounts of all the people mentioned in this book? Not really. Anyone who has carefully followed the Syrian conflict over the years must have read stories of human tragedy, much like the ones recorded in this book. The experiences, grisly and macabre to the point of incredulity, are not unique in the Syrian civil war context. Moreover, the organisation, whose findings make us question her account of a significant incident, has also come up with countless briefings and reports that substantiate her other stories: the agony of living in an area under constant aerial strikes; the dismal state of prisoners in government’s cells, et al.

Does this compromise the credibility of this book as an honest and impartial account of a civil war? This book does not claim to be an unbiased account of the war in Syria, and it is not. It just records the voices of people stuck in a brutal civil war. Her cast of characters, almost all from the rebel forces, and the way she deals with the incidence of massacre in Alawite villages, rightly prompt scepticism, but war reporting in Syria has been difficult, tinged with political biases and often times it has relied on information not independently verifiable, that hardly captures the complexity of the issue, and on pictures that evoke indignation but yield little political insight.

The Syrian conflict is a complex phenomenon, and demands appreciation of its multifarious factors that make it a particularly brutal and long-lasting war. The Syrian conflict is an insurrection against the government, sectarian tussle, fight for regional hegemony and major powers rivalry wrapped into one.

One of the most beautiful things about this book is how it beautifully captures the resilience of people in the face of adversity and how it demonstrates their sense of humour. “Do you know the joke about the genie in the lamp?” one of Mariam’s nieces asked. “A man found a lamp, rubbed it and summoned its genie. ‘Your wish is my command,’ the genie told the man. ‘Great,’ the man said. ‘I need a bottle of cooking gas.’ The next day, the man rubbed the lamp again, summoning an irate genie. ‘What do you want?’ the genie asked. ‘I have run out of diesel,’ the man said. ‘Could not you have waited a few days?’ the genie replied. ‘Now I have lost my spot in the queue for the cooking gas.” There are moments that show human capacity to salvage the best of humanity in the worst of circumstances. After having been stripped of his dignity in prison, this is what Suleiman wrote in his cell, “I’ll leave, I’ll leave, but before that I will give a rose to everyone who mistreated me. I will pardon all who hurt me.” May be such thoughts are the only hope in a country torn by civil war and sectarianism.

The author is a researcher at Islamabad Policy Research Institute