Modern Pakistani pop culture is a cultural extension of the upper echelons of urban middle-class Pakistan – in spite of the fact that acts such as Sajjad Ali, Nazia and Zoheb, Abrar-ul-Haq, Atif Aslam, and, to a certain extent, Junoon and Vital Signs, often managed to create some aesthetic and social relevance within the more populist sections of popular culture in Pakistan.

Modern pop acts in the country who have largely appeared from (and cater to) particular corners of the urban classes would not have been able to make it to the mainstream scheme of things on their own without the financial and promotional muscle of pop-friendly multinationals. Nor would they have been able to sprinkle modern electronic aesthetics over the world-weary and folk-tinged tastes of the majority of Pakistani music fans if not helped by the reach of the mainstream media on which the multinationals advertise their brands.

[quote]Shehzad Roy fell for the safe cliché of drone attacks[/quote]

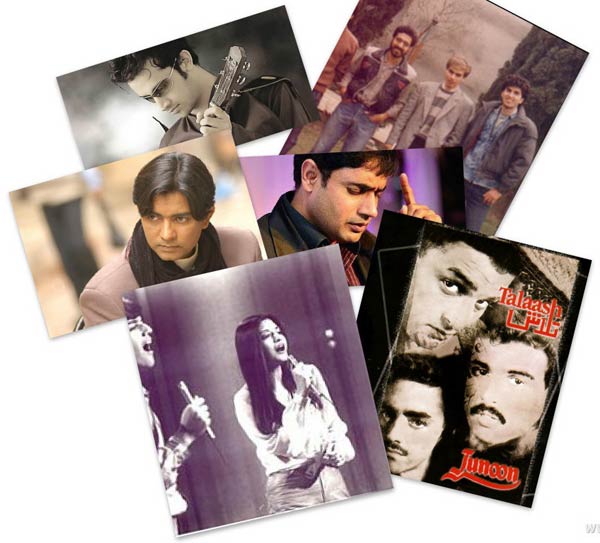

For long the social relevance of Pakistani pop musicians in the larger context of society and politics has remained a featherweight event, even though bands like Junoon made sincere efforts in this direction, albeit not always too convincingly.

Both Pakistani pop and rock music have remained an acquired taste among the masses, whose tastes are still deeply linked to conventional film music, folk music and music associated with South Asia’s ‘shrine culture,’; or music that emerged from the peripheries and surroundings of the tombs of Sufi saints.

Recently, with the country facing an unprecedented spate of political and social problems – such as gruesome terrorism, ‘Talibanisation,’ and economic downturns – pop acts have come under increasing pressure to step out of their comfort zones and state their stance on the more pressing socio-political issues of the hour.

The pressure has mounted also because a majority of Pakistanis – including certain theatre groups, journalists, TV personalities and even the more ‘moderate’ Islamic clerics – have now come out and openly denounced the beliefs and ways of the extremists.

This consensus against religious extremism and the violence it has generated has grown and strengthened. So the question now is, how come pop musicians – most of whom emerge from liberal and educated middle-class backgrounds – have remained eerily quiet about this issue?

Not taking into account songs in this context recorded by performing artistes such as the Baighariat Brigade, Laal and, to a certain extent, Ali Gul Pir, the conventional and more mainstream remnants of the country’s once thriving pop scene have largely decided to stick to singing about the birds and the bees and stay clear of commenting on the more thorny issues.

The most obvious answer has to do with their security. It is said that the musicians are afraid that if they address the issue of religious extremism, they will be attacked and harmed by the extremists.

But when those journalists, TV anchors, theatre groups, some performing artistes and TV personalities who come from the same class as most of their pop brethren, have spoken out against extremism, can the security factor be the only deterrent?

No, security (or lack thereof) is not the only reason. The issue also has a lot to do with the economics and ‘politics’ of the Pakistani pop scene.

In 2009 pop star Shahzad Roy suddenly turned political from being a boy-pop purveyor with an excellent song and video, ‘Laga Reh.’

He created a fantastic platform for himself by becoming one of the first local pop acts who was ready to question the ways and attitude of the clergy, the politicians, and the state.

However, his next video betrayed the boldness that he had exhibited on ‘Laga Reh.’ The next logical step in the narrative he was trying to build should have been the addressing of the issue of terrorism and religious extremism. But Roy fell for a safe cliché instead: American drone attacks.

Courage regarding journalism and art in Pakistan these days should mostly amount to the addressing of issues that a majority of Pakistanis are afraid to raise. Thus, there is absolutely nothing brave or original anymore about registering an artistic protest against the issue of drone attacks. Everybody does it, so what’s the big deal?

How did Roy see the drone attacks as more condemnable than the unprecedented number of terrorist attacks, suicide bombings and the destruction of mosques, shrines and schools by the extremists?

Then in 2008, though a number of local pop acts got together to record a song that pleaded for peace – ‘Yeh Hum Nahin’ – the lyrics were highly ambiguous. Worse was the overall message of the song, ‘this is not us’ (who are causing terror).

The song seemed to have emerged from another narrative plaguing the Pakistani middle-classes regarding terrorism and extremism: the religious extremism and terrorism being experienced by Pakistanis is actually the doing of outside forces, whereas we are nothing short of being innocent saints.

[quote]Most pop acts' first political step was public support for General Pervez Musharraf[/quote]

Many journalists and intellectuals who have decided to break out of the box have now pleaded that the time has arrived for Pakistanis to face up to their own history of violence and intrigue.

They suggest that no serious political and social problem in this country can be convincingly solved if we do not stop to always look for ‘foreign hands’ and ‘sinister anti-Pakistan forces’ for all that goes kaput in Pakistan.

In the light of this, the song’s title should have been ‘Hum Itney Farishtey Bhi Nahein’ (‘We aren’t exactly angels’).

Unfortunately, and ironically, this just cannot be expected from the Pakistani pop scene. Because no matter how liberal and ‘educated’ their background, most pop acts are part of an urban middle-class generation whose first real political step was their public support for General Pervez Musharraf.

And this group also includes many TV artistes, fashion models and designers. Before Musharraf, they remained largely apolitical and highly suspicious of populist democracy which just doesn’t appeal to their fashion and music aesthetics, and, more so, to their economics.

Many pop acts struck gold under Musharraf through advertising, concerts and modelling as Pakistan too tasted the good times of healthy economics that prevailed around the world between 2001 and 2005.

They projected their good fortune as Musharraf’s doing, but when the international economic and political downturn swept aside the soft dictator, Pakistan’s showbiz circles went into a shock of sorts – a shock they are still to recover from, even five years after the renewal of populist democracy in the country.

Asif Zardari and Nawaz Sharif to them will always remain to be crooks, whereas characters like Mullah Fazlullah will never be spoken about or openly condemned. To them he remains to be a phantom.

Populist democracy does not cater well to elite arts, especially when this democracy is struggling. So this is actually a bad time, really, for pop acts to make a political statement. Because representing a class that has largely remained apolitical and with only a superficial and flimsy understanding of political history, most pop acts, both in public and in private, have ended up making a mockery of the whole concept of ‘politicised art.’

For example, musicians like Ali Azmat and fashion designers such as Maria B – though liberal and having a big stake in keeping the Pakistani society pluralistic and open – actually ended up publicly applauding convoluted conspiracy theorists and apologists of terror.

They readily fell in line with cranks who mate Iqbal’s Nietzschean construct of the ‘Shaheen’ with the anti-Semite babblings of Henry Ford, and a distorted history of Pakistan, debunked conspiracy theories, and assorted historical myths, to come up with instant, fast-food explanations about economics, politics and religion!

Who needs books when a self-centred chatterbox is doing all the thinking for you on the mini-screen (or in cyberspace)?

In 2010, Ali Noor of Noorie, who, while giving an interview to an American journalist, said he would never write a song about terrorism because ‘terrorism is not the main issue of the country.’

Wonder which country he was talking about?

Then Strings released a song just before the May 2013 election that joyfully threw lyrical darts at corruption and nepotism but conveniently ignored an issue that has become the country’s leading existentialist threat: Extremist violence and terrorism.

No wonder then, most of these guys eventually landed up in Imran Khan’s rallies.

The above are some of the reasons why I would personally like the local pop acts to remain apolitical because one is asking for a miracle from them to sound coherent, thoughtful and relevant in matters of politics – especially when it concerns terrorism and religious extremism. They have absolutely no clue.

And anyway, the state and environment of Pakistan’s polity and society is such these days that even when artistes (no matter what their art), venture into the open with their apolitical creation, theirs become a political act against those who want to rid society of all art.

So why bother speaking on issues that end up making one sound rather silly; or like someone with a tin-foil antenna on his head, claiming that he is getting all his information from a distant planet.

Modern pop acts in the country who have largely appeared from (and cater to) particular corners of the urban classes would not have been able to make it to the mainstream scheme of things on their own without the financial and promotional muscle of pop-friendly multinationals. Nor would they have been able to sprinkle modern electronic aesthetics over the world-weary and folk-tinged tastes of the majority of Pakistani music fans if not helped by the reach of the mainstream media on which the multinationals advertise their brands.

[quote]Shehzad Roy fell for the safe cliché of drone attacks[/quote]

For long the social relevance of Pakistani pop musicians in the larger context of society and politics has remained a featherweight event, even though bands like Junoon made sincere efforts in this direction, albeit not always too convincingly.

Both Pakistani pop and rock music have remained an acquired taste among the masses, whose tastes are still deeply linked to conventional film music, folk music and music associated with South Asia’s ‘shrine culture,’; or music that emerged from the peripheries and surroundings of the tombs of Sufi saints.

Recently, with the country facing an unprecedented spate of political and social problems – such as gruesome terrorism, ‘Talibanisation,’ and economic downturns – pop acts have come under increasing pressure to step out of their comfort zones and state their stance on the more pressing socio-political issues of the hour.

The pressure has mounted also because a majority of Pakistanis – including certain theatre groups, journalists, TV personalities and even the more ‘moderate’ Islamic clerics – have now come out and openly denounced the beliefs and ways of the extremists.

This consensus against religious extremism and the violence it has generated has grown and strengthened. So the question now is, how come pop musicians – most of whom emerge from liberal and educated middle-class backgrounds – have remained eerily quiet about this issue?

Not taking into account songs in this context recorded by performing artistes such as the Baighariat Brigade, Laal and, to a certain extent, Ali Gul Pir, the conventional and more mainstream remnants of the country’s once thriving pop scene have largely decided to stick to singing about the birds and the bees and stay clear of commenting on the more thorny issues.

The most obvious answer has to do with their security. It is said that the musicians are afraid that if they address the issue of religious extremism, they will be attacked and harmed by the extremists.

But when those journalists, TV anchors, theatre groups, some performing artistes and TV personalities who come from the same class as most of their pop brethren, have spoken out against extremism, can the security factor be the only deterrent?

No, security (or lack thereof) is not the only reason. The issue also has a lot to do with the economics and ‘politics’ of the Pakistani pop scene.

In 2009 pop star Shahzad Roy suddenly turned political from being a boy-pop purveyor with an excellent song and video, ‘Laga Reh.’

He created a fantastic platform for himself by becoming one of the first local pop acts who was ready to question the ways and attitude of the clergy, the politicians, and the state.

However, his next video betrayed the boldness that he had exhibited on ‘Laga Reh.’ The next logical step in the narrative he was trying to build should have been the addressing of the issue of terrorism and religious extremism. But Roy fell for a safe cliché instead: American drone attacks.

Courage regarding journalism and art in Pakistan these days should mostly amount to the addressing of issues that a majority of Pakistanis are afraid to raise. Thus, there is absolutely nothing brave or original anymore about registering an artistic protest against the issue of drone attacks. Everybody does it, so what’s the big deal?

How did Roy see the drone attacks as more condemnable than the unprecedented number of terrorist attacks, suicide bombings and the destruction of mosques, shrines and schools by the extremists?

Then in 2008, though a number of local pop acts got together to record a song that pleaded for peace – ‘Yeh Hum Nahin’ – the lyrics were highly ambiguous. Worse was the overall message of the song, ‘this is not us’ (who are causing terror).

The song seemed to have emerged from another narrative plaguing the Pakistani middle-classes regarding terrorism and extremism: the religious extremism and terrorism being experienced by Pakistanis is actually the doing of outside forces, whereas we are nothing short of being innocent saints.

[quote]Most pop acts' first political step was public support for General Pervez Musharraf[/quote]

Many journalists and intellectuals who have decided to break out of the box have now pleaded that the time has arrived for Pakistanis to face up to their own history of violence and intrigue.

They suggest that no serious political and social problem in this country can be convincingly solved if we do not stop to always look for ‘foreign hands’ and ‘sinister anti-Pakistan forces’ for all that goes kaput in Pakistan.

In the light of this, the song’s title should have been ‘Hum Itney Farishtey Bhi Nahein’ (‘We aren’t exactly angels’).

Unfortunately, and ironically, this just cannot be expected from the Pakistani pop scene. Because no matter how liberal and ‘educated’ their background, most pop acts are part of an urban middle-class generation whose first real political step was their public support for General Pervez Musharraf.

And this group also includes many TV artistes, fashion models and designers. Before Musharraf, they remained largely apolitical and highly suspicious of populist democracy which just doesn’t appeal to their fashion and music aesthetics, and, more so, to their economics.

Many pop acts struck gold under Musharraf through advertising, concerts and modelling as Pakistan too tasted the good times of healthy economics that prevailed around the world between 2001 and 2005.

They projected their good fortune as Musharraf’s doing, but when the international economic and political downturn swept aside the soft dictator, Pakistan’s showbiz circles went into a shock of sorts – a shock they are still to recover from, even five years after the renewal of populist democracy in the country.

Asif Zardari and Nawaz Sharif to them will always remain to be crooks, whereas characters like Mullah Fazlullah will never be spoken about or openly condemned. To them he remains to be a phantom.

Populist democracy does not cater well to elite arts, especially when this democracy is struggling. So this is actually a bad time, really, for pop acts to make a political statement. Because representing a class that has largely remained apolitical and with only a superficial and flimsy understanding of political history, most pop acts, both in public and in private, have ended up making a mockery of the whole concept of ‘politicised art.’

For example, musicians like Ali Azmat and fashion designers such as Maria B – though liberal and having a big stake in keeping the Pakistani society pluralistic and open – actually ended up publicly applauding convoluted conspiracy theorists and apologists of terror.

They readily fell in line with cranks who mate Iqbal’s Nietzschean construct of the ‘Shaheen’ with the anti-Semite babblings of Henry Ford, and a distorted history of Pakistan, debunked conspiracy theories, and assorted historical myths, to come up with instant, fast-food explanations about economics, politics and religion!

Who needs books when a self-centred chatterbox is doing all the thinking for you on the mini-screen (or in cyberspace)?

In 2010, Ali Noor of Noorie, who, while giving an interview to an American journalist, said he would never write a song about terrorism because ‘terrorism is not the main issue of the country.’

Wonder which country he was talking about?

Then Strings released a song just before the May 2013 election that joyfully threw lyrical darts at corruption and nepotism but conveniently ignored an issue that has become the country’s leading existentialist threat: Extremist violence and terrorism.

No wonder then, most of these guys eventually landed up in Imran Khan’s rallies.

The above are some of the reasons why I would personally like the local pop acts to remain apolitical because one is asking for a miracle from them to sound coherent, thoughtful and relevant in matters of politics – especially when it concerns terrorism and religious extremism. They have absolutely no clue.

And anyway, the state and environment of Pakistan’s polity and society is such these days that even when artistes (no matter what their art), venture into the open with their apolitical creation, theirs become a political act against those who want to rid society of all art.

So why bother speaking on issues that end up making one sound rather silly; or like someone with a tin-foil antenna on his head, claiming that he is getting all his information from a distant planet.