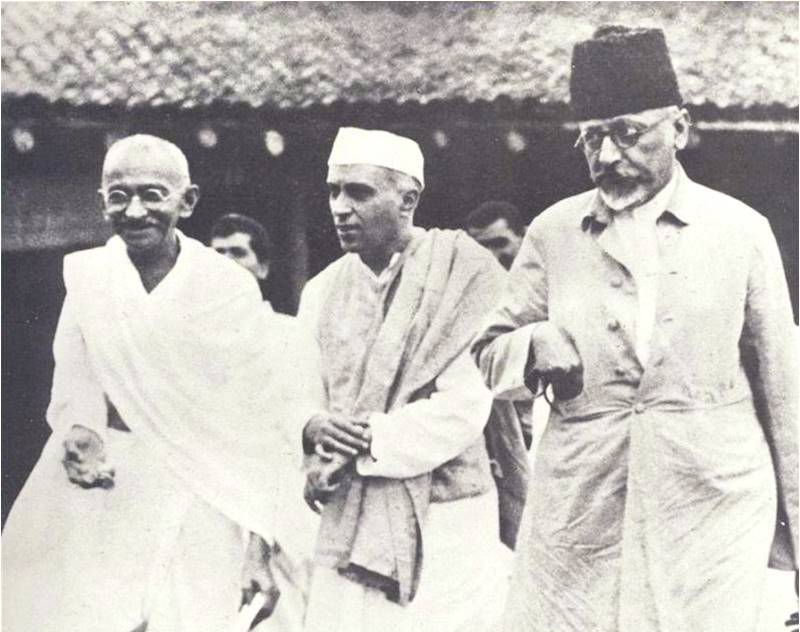

Since the word “Partition” has figured in the discourse on CAA, NCR, NPR the mind turns towards Maulana Azad, who was so fiercely opposed to the country’s division. By a coincidence, February 22 happens to be the 61st death anniversary of Maulana Azad. Exactly 30 years after that date, those 30 precious pages of India Wins Freedom were taken out of the National Archives which the Maulana had kept away so that all his contemporaries were not around to face embarrassment from the exposures, if any, contained in those pages.

And there were embarrassments galore. The Intelligentsia and the ruling class were disinclined to give much credence to what the Maulana wrote. The absence of debate after the publication of the “complete” edition of India Wins Freedom in 1988 was deafening. Nor were threads picked up subsequently in the interest of history. For instance, the Maulana’s assertion that towards the end of the negotiations with the British, Sardar Patel appeared to be more convinced of the Two Nation Theory than Jinnah deserves to be noted. Rebut it, if need be. To avoid the brutalities which followed the announcement of the Partition plan, an idea was mooted to keep the British Army united.

As a temporary measure, it seemed a sensible idea. But to the Maulana’s surprise, most adamantly opposed to a United Army “even for a day” was the arch pacifist Rajendra Prasad. His opposition was conditioned by a fear that a United Army would remain an “unfinished” business of Partition. And who knows how long this “unfinished business” would linger? What if a United Army becomes a pressure point for reversing Partition? The eagerness to hold onto Partition is manifest in the behaviour of a long list of leaders. The Maulana describes in detail how Sardar Patel had convinced even Mahatma Gandhi that Partition was the best course under the circumstances.

Just as it is today, Assam was the key state in focus in 1946-47. The crucial role it is playing today in the CAA, NRC discourse is not surprising. Fired by sub nationalism and cultural pride, Chief Minister Gopinath Bordoloi enlisted Mahatma Gandhi’s support in rejecting the Cabinet Mission proposal yoking Assam with Bengal in what was described as Zone C in the Mission’s plan. The country was to be stabilized under groups: A, B and C.

The Cabinet Mission’s was the last effort to keep India united. It was endorsed by the Congress on July 7, 1946. But two surprising events made Partition inevitable. One was Assam’s firm rejection of being grouped with Bengal. It feared then as it does now, of being inundated with migration. Second was the new Congress President Jawaharlal Nehru’s fateful press conference in Mumbai on July 10. Nehru declared that all that had been agreed with the Cabinet Mission and Jinnah would have to be ratified by a constituent assembly. This stipulation was not in the agreement. Little wonder Jinnah picked up the marbles and walked out of the game. Partition became inevitable.

The Maulana’s opposition to Partition was absolute. He was eloquent about the cultural commerce of over 1,100 years which he always described as his heritage. “We handed over our wealth to her (Bharat) and she unlocked for us the door of her own riches.” He was unambiguous: “Partition would be unadulterated Hindu Raj.” In the light of experience, was he wrong? Was Partition the Congress’s gift to the Hindu right? A Muslim country next door to be hated in perpetuity; an unresolved problem of Muslim majority Kashmir. A 200 million Muslim population – a lethal mix for dedicated Hindu Rashtra Bhakts – all under the canopy of global Islamophobia.

If Pakistan was so much against the interests of Muslims themselves, as the Maulana never tired of saying, why should such a large section of Indian Muslims be swept away by its lure? The Maulana’s response to this query was unique:

“The answer is to be found in the attitude of certain communal extremists among the Hindus. When the Muslim League began to speak of Pakistan, they (Hindus) began to read into the scheme a sinister pan Islamic conspiracy. They opposed the idea out of the fear that it foreshadowed a combination of Indian Muslims with trans-Indian Muslim states. This fierce opposition acted as an incentive to the adherents of the League. With simple though untenable logic, they argued that if Hindus were so opposed to Pakistan, surely, it must be of benefit to Muslims. Reason was impossible in an atmosphere of emotional frenzy thus created.” Is the ogre of three Muslim majority states a continuation of the line the Maulana had spotted 75 years ago?

He was convinced that the “chapter of communal differences was a transient phase of Indian Life.” “Differences would persist just as opposition among political parties will continue but, it will be based not on religion but on economic and political issues.”

Nehru’s last interview with Arnold Michaelis in May, 1964, shortly before his death is revealing. First, he dismisses Jinnah almost as a non-entity in the freedom struggle. “He was not in the fight for freedom.” In fact the Muslim League was set up by the British to “divide us,” he said. He further said that he, like Gandhiji and others, were opposed to Partition. “Then why did you accept Partition?” Michaelis asks. Nehru’s reply is cryptic.

“I decided it was better to part than to have constant trouble.” The trouble Nehru refers to was clearly the continuous bickering between the Congress and Muslim League in the interim government of 1946. Obviously Nehru was exasperated by the apparent incompatibilities in the interim government. While giving vent to his exasperation, did India’s first Prime Minister spare a thought for the minorities, primarily Muslims, 200 million at current reckoning who were riveted on him as their leader. Maulana Azad spelt out exactly what their fate would be. And surprising though it is, the Maulana was nowhere near Nehru’s charismatic hold on a community which learnt only in retrospect that they had been let down by the leader they adored.

The writer is a journalist based in India

And there were embarrassments galore. The Intelligentsia and the ruling class were disinclined to give much credence to what the Maulana wrote. The absence of debate after the publication of the “complete” edition of India Wins Freedom in 1988 was deafening. Nor were threads picked up subsequently in the interest of history. For instance, the Maulana’s assertion that towards the end of the negotiations with the British, Sardar Patel appeared to be more convinced of the Two Nation Theory than Jinnah deserves to be noted. Rebut it, if need be. To avoid the brutalities which followed the announcement of the Partition plan, an idea was mooted to keep the British Army united.

Just as it is today, Assam was the key state in focus in 1946-47. The crucial role it is playing today in the CAA, NRC discourse is not surprising

As a temporary measure, it seemed a sensible idea. But to the Maulana’s surprise, most adamantly opposed to a United Army “even for a day” was the arch pacifist Rajendra Prasad. His opposition was conditioned by a fear that a United Army would remain an “unfinished” business of Partition. And who knows how long this “unfinished business” would linger? What if a United Army becomes a pressure point for reversing Partition? The eagerness to hold onto Partition is manifest in the behaviour of a long list of leaders. The Maulana describes in detail how Sardar Patel had convinced even Mahatma Gandhi that Partition was the best course under the circumstances.

Just as it is today, Assam was the key state in focus in 1946-47. The crucial role it is playing today in the CAA, NRC discourse is not surprising. Fired by sub nationalism and cultural pride, Chief Minister Gopinath Bordoloi enlisted Mahatma Gandhi’s support in rejecting the Cabinet Mission proposal yoking Assam with Bengal in what was described as Zone C in the Mission’s plan. The country was to be stabilized under groups: A, B and C.

The Cabinet Mission’s was the last effort to keep India united. It was endorsed by the Congress on July 7, 1946. But two surprising events made Partition inevitable. One was Assam’s firm rejection of being grouped with Bengal. It feared then as it does now, of being inundated with migration. Second was the new Congress President Jawaharlal Nehru’s fateful press conference in Mumbai on July 10. Nehru declared that all that had been agreed with the Cabinet Mission and Jinnah would have to be ratified by a constituent assembly. This stipulation was not in the agreement. Little wonder Jinnah picked up the marbles and walked out of the game. Partition became inevitable.

The Maulana’s opposition to Partition was absolute. He was eloquent about the cultural commerce of over 1,100 years which he always described as his heritage. “We handed over our wealth to her (Bharat) and she unlocked for us the door of her own riches.” He was unambiguous: “Partition would be unadulterated Hindu Raj.” In the light of experience, was he wrong? Was Partition the Congress’s gift to the Hindu right? A Muslim country next door to be hated in perpetuity; an unresolved problem of Muslim majority Kashmir. A 200 million Muslim population – a lethal mix for dedicated Hindu Rashtra Bhakts – all under the canopy of global Islamophobia.

If Pakistan was so much against the interests of Muslims themselves, as the Maulana never tired of saying, why should such a large section of Indian Muslims be swept away by its lure? The Maulana’s response to this query was unique:

“The answer is to be found in the attitude of certain communal extremists among the Hindus. When the Muslim League began to speak of Pakistan, they (Hindus) began to read into the scheme a sinister pan Islamic conspiracy. They opposed the idea out of the fear that it foreshadowed a combination of Indian Muslims with trans-Indian Muslim states. This fierce opposition acted as an incentive to the adherents of the League. With simple though untenable logic, they argued that if Hindus were so opposed to Pakistan, surely, it must be of benefit to Muslims. Reason was impossible in an atmosphere of emotional frenzy thus created.” Is the ogre of three Muslim majority states a continuation of the line the Maulana had spotted 75 years ago?

He was convinced that the “chapter of communal differences was a transient phase of Indian Life.” “Differences would persist just as opposition among political parties will continue but, it will be based not on religion but on economic and political issues.”

Nehru’s last interview with Arnold Michaelis in May, 1964, shortly before his death is revealing. First, he dismisses Jinnah almost as a non-entity in the freedom struggle. “He was not in the fight for freedom.” In fact the Muslim League was set up by the British to “divide us,” he said. He further said that he, like Gandhiji and others, were opposed to Partition. “Then why did you accept Partition?” Michaelis asks. Nehru’s reply is cryptic.

“I decided it was better to part than to have constant trouble.” The trouble Nehru refers to was clearly the continuous bickering between the Congress and Muslim League in the interim government of 1946. Obviously Nehru was exasperated by the apparent incompatibilities in the interim government. While giving vent to his exasperation, did India’s first Prime Minister spare a thought for the minorities, primarily Muslims, 200 million at current reckoning who were riveted on him as their leader. Maulana Azad spelt out exactly what their fate would be. And surprising though it is, the Maulana was nowhere near Nehru’s charismatic hold on a community which learnt only in retrospect that they had been let down by the leader they adored.

The writer is a journalist based in India