Readers may remember the scene in that marvelous movie, The Wizard of Oz, when Dorothy steps out of the sepia tones of her house which has landed in the fabled land of Oz, blown there by the fierce winds of a tornado, into a land bathed in color, primarily green. Well, after an absence of only a couple of years, my return to my home state of California has been almost the reverse of Dorothy’s landing in Oz—I feel like I have gone from the green and colorful California of my memory to the burnt-out tones of a desert.

I had not imagined either the visual effects or the real ones of the 4-year drought that has grabbed California by its throat. The green and bounteous state I grew up in has become brown and arid. To borrow words from a novel I once skimmed, “I grew up at the edge of the ocean and knew it was paradise, and better than Eden, which was only a garden.” But drought has killed the garden and the paradise is now a brown one.

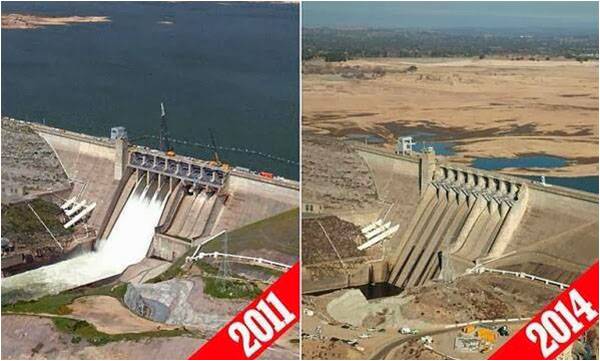

The photos above are taken from a site that charts the extent of the California drought. They are of Folsom Dam, which was built about 60 years ago for flood control in the Sacramento Valley. The photo on the left, taken as readers can see 5 years ago which, in the upper left hand corner shows dimly in the distance the beach at which I worked as a youth; the one on the right, taken 3 years later, shows that the great lake that was behind the dam is now mostly beach. In fact, I am told it has become worse a year later.

The effects are widespread, pervasive, and more worrying, cumulative. Nearly 90 percent of the state is suffering from severe or extreme drought. Satellite imaging shows that large swaths of California soil are bone dry, the cumulative effect of four straight years of drought. Hit worse, of course, is agriculture, and California has been the breadbasket of America for many decades. The drought is now estimated to result in a $2.7 billion dollar loss to the state’s agricultural economy according to The University of California, Davis, the State’s leading agricultural university.

That said, so far the losses are not that serious, for California or for the nation. The 2.7 billion is a relatively small decline for California’s massive economy. (California had the 8thlargest economy in the world, at about $2.2 trillion, in 2013, thus just a tad smaller than Brazil but larger than Russia and Italy and most of the other nations on the planet.) Agriculture accounts for only about 2 percent of California’s gross domestic product (GDP). Despite what seems a high number, the total expected loss to California’s $45 billion agricultural economy is 6 percent. Perhaps the most troublesome effect in the state so far is that about 17,000 agricultural jobs were lost last year, and that number could be doubled this year.

Much of that impact will, of course, be in my home territory of California’s Central Valley, a 450 mile long valley carved by two great rivers, the Sacramento, and the San Joaquin, a stretch of land that one analyst suggests may be the single most productive tract of land in the world, producing 230 varieties of vegetables and fruits and nuts, the botanical origins of which span the globe. Eighty percent of the world’s almonds come from this valley as well as most of the American tomatoes. In fact the list of produce that California is the major producer of (and mostly in the Central Valley) comprises just about every fruit and vegetable Americans eat.

From a national perspective, in the short run, the most worrisome aspect of the drought is the possible inflationary impact through higher food prices. Since California produces overall about one third of Americas fruits and vegetables, and much more of certain food items, a general escalation in their prices because of shortfalls in their production is possible if the California drought continues to worsen. But most economists discount this as very likely, believing that other producers in other parts of the US could pick up the slack, and more likely California producers will move production to areas in which the drought is not so severe.

But, not so fast there, please. If the drought persists, it could have a greater economic impact on prices than this rather rosy analysis suggests. Food represents nearly 5% of gross domestic product, 13% of household expenditures. Over 9% of US employment and 14% of manufacturing jobs involve food production of some sort. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that if the drought endures for several more years, there will be an inflationary impact.

There is a longer-run problem that is not much discussed or even recognized. This is that, perhaps, the US is too reliant on California for its fresh veggies and fruit. Most of the produce grown in California can be grown elsewhere in the country. California became the nation’s food basket by a combination of climate, soil and vast water resources in its rivers and in its soil (the ground water aquifers have been life savers during this drought, but are quickly being used up now, the ground is sinking, and farmers are drilling down thousands of feet to get more ground water). Even if the drought ends next year, and the rain and snowfall exceed past good years, it will take decades to rebuild the ground water resources.

However, I guess what my generation misses most is the greenness and freshness of the Oz we grew up in. All over Sacramento, trees are dying and grass is brown from a lack of water. The State Government has decreed a rather Spartan regime of water restrictions which outlaw watering a lawn and trees more than twice a week. In a climate in which, even in good years it doesn’t rain in the summer, and the daytime temperature often flirts with three figures (Fahrenheit), this is surely a way to kill off the trees and grass. The photo below is, perhaps, a view of the future—a Sacramento in which cactus and rocks decorate the houses, not trees and grass.

Mark Twain said that what makes California special is its people who, he wrote in “Roughing It” his account of his journey to the State and to Nevada to become a silver miner (he became a newspaper writer instead proving not very good at mining), “gave to California a name for getting up astounding enterprises and rushing them through with a magnificent dash and daring and a recklessness of cost or consequences…and when she projects a new surprise the grave world smiles as usual and says, “Well, that is California all over.” Maybe Californians will rise to the challenges of water insufficiency, even to the point of growing cactus.

About 100 years after Mark Twain gave Californians such good marks, in 1977, the Eagles, great favorites among my age group in those years, and popular abroad also, produced “Hotel California,” one of their big hits, and one of the more obscure. Their view of Californians, however, seemed distinctly different than Twain’s. The song ended with the narrator trying to flee, and saying “Last thing I remember, I was running for the door, I had to find the passage back to the place I was before. Relax said the night man, we are programmed to receive. You can check-out any time you like, but you can never leave! “

There were many questions about the meaning of this song, especially the last verse. One of its writers explained it as “a journey from innocence to experience...that’s all.” Perhaps California, having come from too much water to now, maybe, too little, has taken the same journey.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Chief of Mission in Liberia

I had not imagined either the visual effects or the real ones of the 4-year drought that has grabbed California by its throat. The green and bounteous state I grew up in has become brown and arid. To borrow words from a novel I once skimmed, “I grew up at the edge of the ocean and knew it was paradise, and better than Eden, which was only a garden.” But drought has killed the garden and the paradise is now a brown one.

The photos above are taken from a site that charts the extent of the California drought. They are of Folsom Dam, which was built about 60 years ago for flood control in the Sacramento Valley. The photo on the left, taken as readers can see 5 years ago which, in the upper left hand corner shows dimly in the distance the beach at which I worked as a youth; the one on the right, taken 3 years later, shows that the great lake that was behind the dam is now mostly beach. In fact, I am told it has become worse a year later.

The effects are widespread, pervasive, and more worrying, cumulative. Nearly 90 percent of the state is suffering from severe or extreme drought. Satellite imaging shows that large swaths of California soil are bone dry, the cumulative effect of four straight years of drought. Hit worse, of course, is agriculture, and California has been the breadbasket of America for many decades. The drought is now estimated to result in a $2.7 billion dollar loss to the state’s agricultural economy according to The University of California, Davis, the State’s leading agricultural university.

That said, so far the losses are not that serious, for California or for the nation. The 2.7 billion is a relatively small decline for California’s massive economy. (California had the 8thlargest economy in the world, at about $2.2 trillion, in 2013, thus just a tad smaller than Brazil but larger than Russia and Italy and most of the other nations on the planet.) Agriculture accounts for only about 2 percent of California’s gross domestic product (GDP). Despite what seems a high number, the total expected loss to California’s $45 billion agricultural economy is 6 percent. Perhaps the most troublesome effect in the state so far is that about 17,000 agricultural jobs were lost last year, and that number could be doubled this year.

The green and bounteous state I grew up in has become brown and arid

Much of that impact will, of course, be in my home territory of California’s Central Valley, a 450 mile long valley carved by two great rivers, the Sacramento, and the San Joaquin, a stretch of land that one analyst suggests may be the single most productive tract of land in the world, producing 230 varieties of vegetables and fruits and nuts, the botanical origins of which span the globe. Eighty percent of the world’s almonds come from this valley as well as most of the American tomatoes. In fact the list of produce that California is the major producer of (and mostly in the Central Valley) comprises just about every fruit and vegetable Americans eat.

From a national perspective, in the short run, the most worrisome aspect of the drought is the possible inflationary impact through higher food prices. Since California produces overall about one third of Americas fruits and vegetables, and much more of certain food items, a general escalation in their prices because of shortfalls in their production is possible if the California drought continues to worsen. But most economists discount this as very likely, believing that other producers in other parts of the US could pick up the slack, and more likely California producers will move production to areas in which the drought is not so severe.

But, not so fast there, please. If the drought persists, it could have a greater economic impact on prices than this rather rosy analysis suggests. Food represents nearly 5% of gross domestic product, 13% of household expenditures. Over 9% of US employment and 14% of manufacturing jobs involve food production of some sort. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that if the drought endures for several more years, there will be an inflationary impact.

There is a longer-run problem that is not much discussed or even recognized. This is that, perhaps, the US is too reliant on California for its fresh veggies and fruit. Most of the produce grown in California can be grown elsewhere in the country. California became the nation’s food basket by a combination of climate, soil and vast water resources in its rivers and in its soil (the ground water aquifers have been life savers during this drought, but are quickly being used up now, the ground is sinking, and farmers are drilling down thousands of feet to get more ground water). Even if the drought ends next year, and the rain and snowfall exceed past good years, it will take decades to rebuild the ground water resources.

However, I guess what my generation misses most is the greenness and freshness of the Oz we grew up in. All over Sacramento, trees are dying and grass is brown from a lack of water. The State Government has decreed a rather Spartan regime of water restrictions which outlaw watering a lawn and trees more than twice a week. In a climate in which, even in good years it doesn’t rain in the summer, and the daytime temperature often flirts with three figures (Fahrenheit), this is surely a way to kill off the trees and grass. The photo below is, perhaps, a view of the future—a Sacramento in which cactus and rocks decorate the houses, not trees and grass.

Mark Twain said that what makes California special is its people who, he wrote in “Roughing It” his account of his journey to the State and to Nevada to become a silver miner (he became a newspaper writer instead proving not very good at mining), “gave to California a name for getting up astounding enterprises and rushing them through with a magnificent dash and daring and a recklessness of cost or consequences…and when she projects a new surprise the grave world smiles as usual and says, “Well, that is California all over.” Maybe Californians will rise to the challenges of water insufficiency, even to the point of growing cactus.

About 100 years after Mark Twain gave Californians such good marks, in 1977, the Eagles, great favorites among my age group in those years, and popular abroad also, produced “Hotel California,” one of their big hits, and one of the more obscure. Their view of Californians, however, seemed distinctly different than Twain’s. The song ended with the narrator trying to flee, and saying “Last thing I remember, I was running for the door, I had to find the passage back to the place I was before. Relax said the night man, we are programmed to receive. You can check-out any time you like, but you can never leave! “

There were many questions about the meaning of this song, especially the last verse. One of its writers explained it as “a journey from innocence to experience...that’s all.” Perhaps California, having come from too much water to now, maybe, too little, has taken the same journey.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Chief of Mission in Liberia