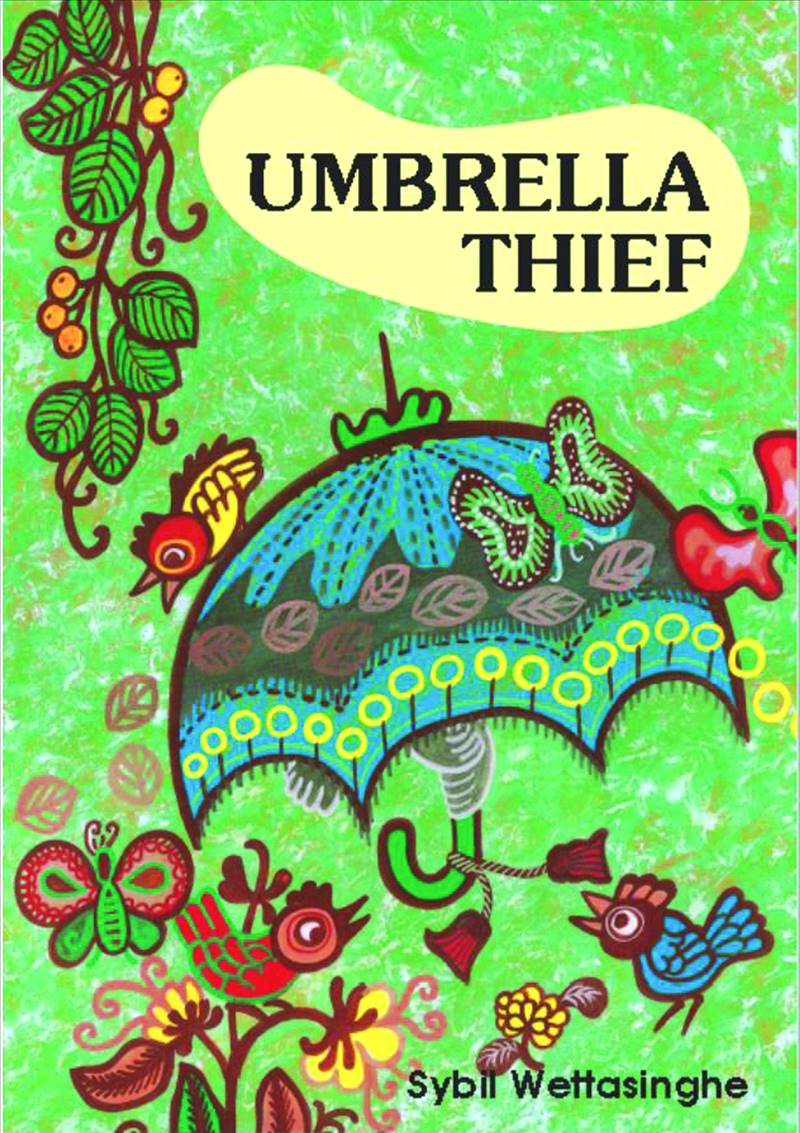

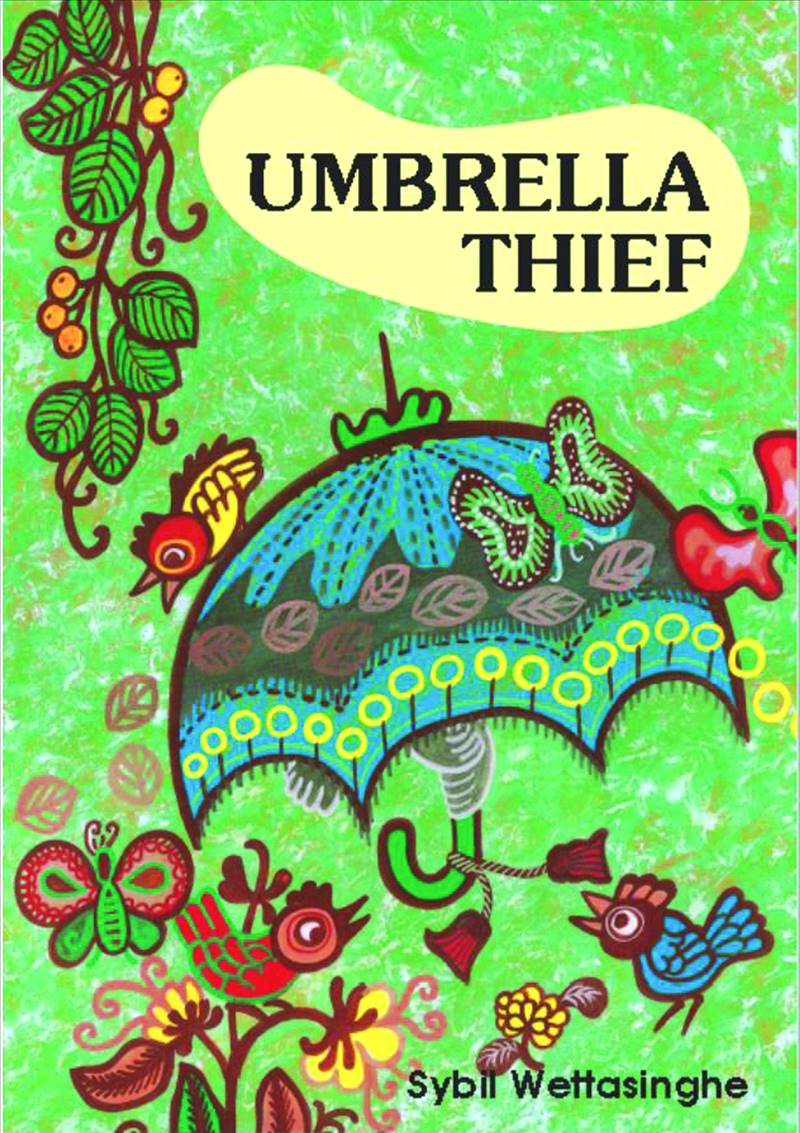

When the children’s section of the Sinhalese-language Janatha newspaper published a story with illustrations titled Kuda Hora (The Umbrella Thief) in 1956, Sybil Wettasinghe, then 29, had little idea that this would be the beginning of an acclaimed literary career that would bring her love and admiration well beyond the shores of her native Sri Lanka. The heart-warming tale of a monkey stealing umbrellas was the catalyst to her publishing more than 200 children’s stories over the span of six and a half decades.

Wettasinghe, who passed away in the early hours of the 1st of July, 2020, was a national icon in Sri Lanka, a symbol of the rapid strides in women’s empowerment the country made close on the heels of its independence. Born in the village of Gintota in the southern coast of what was then the British crown colony of Ceylon, her family, part of the early wave of rural to urban migration, moved to Colombo when she was a child.

In an autobiography of her childhood titled Eternally Yours, she gives us a rare glimpse of a life that is now unrecognizable in Colombo. Among the many vendors that would visit her home was the “bookman” who would carry a tall pile of books on his head visiting homes where there were children. “He could be called a walking library, for in his pile of books which he spread on our verandah floor were fantastic fairy tales,” she wrote. Her first introduction to children’s stories by Hans Christian Anderson was from this bookman. “I was fascinated with the pictures in these books that I yearned to read English,” Wettasinghe wrote.

Equally comfortable with writing in her native Sinhalese and English, The Umbrella Thief, which came out as a book in 1956, became one of the most read stories of all time on the island. The simple protagonist, Kiri Mama, who sees an umbrella for the first time when he visits Colombo from his village, and buys it and takes it home, is one of the most beloved characters in Sri Lankan literature.

The Umbrella Thief, which Wettasinghe wrote for her “best fan and critic,” her husband Don Dharmapala (who would later head Sri Lankan media giant Lake House Publications), was a path-breaker in children’s literature in the country. At that time Sinhalese literature for children basically comprised of translation of European classics. The Umbrella Thief, with its illustrations managed to herald in a new era in children’s literature in the country. “Kuda Hora was the first Sinhalese book to completely marry words and pictures,” Sri Lankan playwright, journalist and poet Regi Siriwardena once remarked.

It was Wettasinghe’s ability to connect deeply with her village roots from an urban setting that made her work resonate widely with Sri Lankans of all backgrounds.

Religion and folklore

Hailing from a religious family, Wettasinghe incorporated Buddhist art and legends into her stories. Her 1965 story Vesak Lantern is also considered a timeless classic in Sri Lanka and other countries with a large Buddhist population.

The story is a nostalgic look at the excitement and preparation for the most important festival for the followers of the Buddha. The occasion was something that Wettasinghe looked forward to from her early childhood, and she shared vivid memories of her grandfather making his paper lanterns: “Coloured paper, scissors, cutters, rice paste and bamboo strips were scattered all over our floor during the preceding Vesak festival,” she wrote excitedly from her childhood.

The story Vesak Lantern propelled Wettasinghe to international fame, and it was awarded the Isabel Hutton Prize by the Women’s Council of England for Asian women writers in 1965. It was also featured in an anthology of Asian writing by UNESCO’s Asian Cultural Centre and in an anthology produced by the Pontificial Catholic University of Chile in 1998.

The Umbrella Thief and Vesak Lantern were both dramatized and adapted to children’s theatre.

Wettasinghe was also interested in the folklore and beliefs that predate and survived the Sinhalese community’s embracing of Buddhism. As a child, she heard many folktales from her Athamma (grandmother).

Her father had a friend who was an exorcist-cum-astrologer, who could perform ‘Kodivina’ or black magic to ward off evil eyes. She wrote about witnessing a “Mahanilanga Rakshya baliya”, an ancient devil dance to ward off evil spirits. The magic that was also so prevalent in her more than 200 stories was not of the dark kind.

Wettasinghe was also very familiar with Biblical stories as her primary education was at the Holy Family Convent in Colombo’s Bambalapitiya. In her autobiography she described her first encounter with a European nun, after gazing at a statue of Jesus Christ: “A rustle of beads, footsteps and the swish of a skirt fell on our ears. Instantly a strange looking fair person stood before us. Only her fair face and hands were visible, for she wore a long white gathered floor length skirt and on the top part of her body was a neck-hugging elbow length flared slip-on over a long sleeved blouse. Around her face was a pin frilled white bonnet, and the back of her head was covered with a black flimsy veil reaching down to her waist. A long bead chain dangled from her waistline with a silver cross at the end.” Wettasinghe, then six, froze, while her younger brother the wet the floor out of fear.

She would thrive in the cosmopolitan environment of the school and appreciate religious icons and paintings. Decades later, Wettasinghe would be invited to make illustrations for a Sinhalese edition of a children’s Bible (Deeptha Lama Maga). This was a task she took with the greatest care, especially when she had to illustrate the story of Adam and Eve. She won a special prize for those illustrations at the Biennial of Illustration Bratislava in 1989.

Success in Japan

Wettasinghe’s stories were well received in Japan. The Umbrella Thief (Kasadarobou in Japanese) was published in the country in 1982, when it became almost instantly famous by receiving an honourable mention at the third Noma Concours for Picture Book Illustrations. A few years later, it was voted the Japanese Library Association Award as the most popular children’s book.

Wettasinghe would make several trips to Japan for public exhibitions of her illustrations. Inspired by the aesthetic beauty of the country, her later artwork would have a clear hint of Aizuri-e or Japanese prints done in shades of blue.

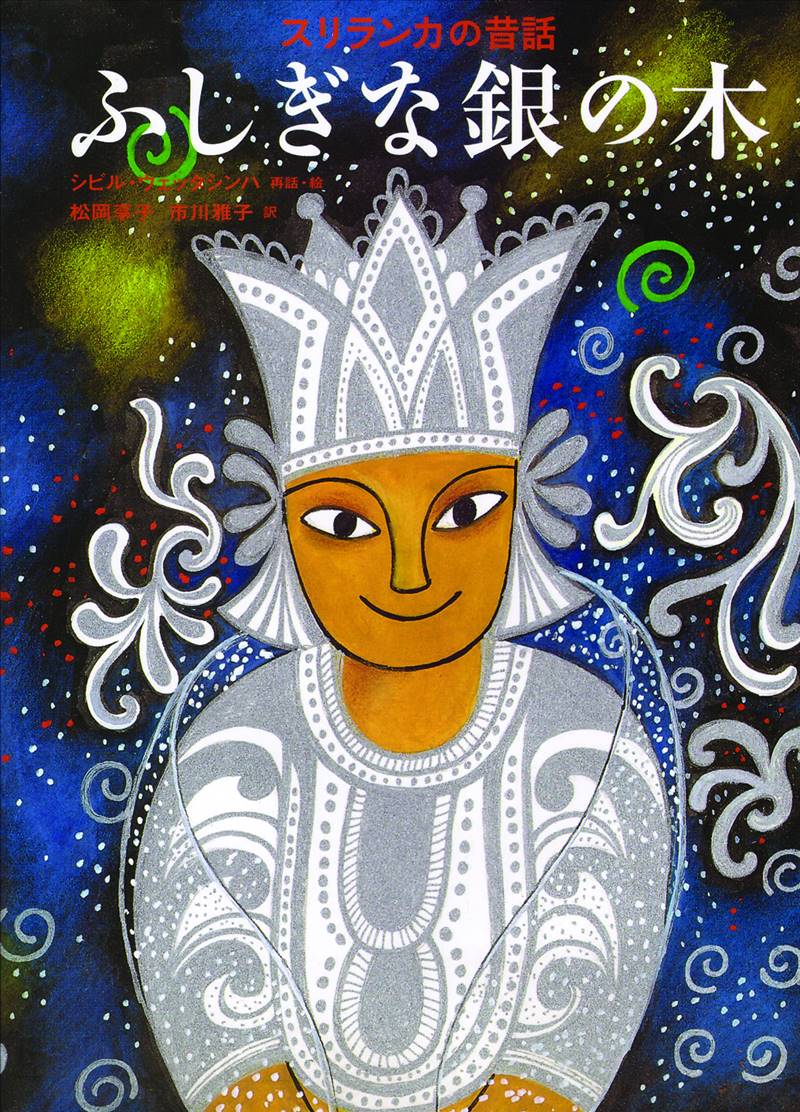

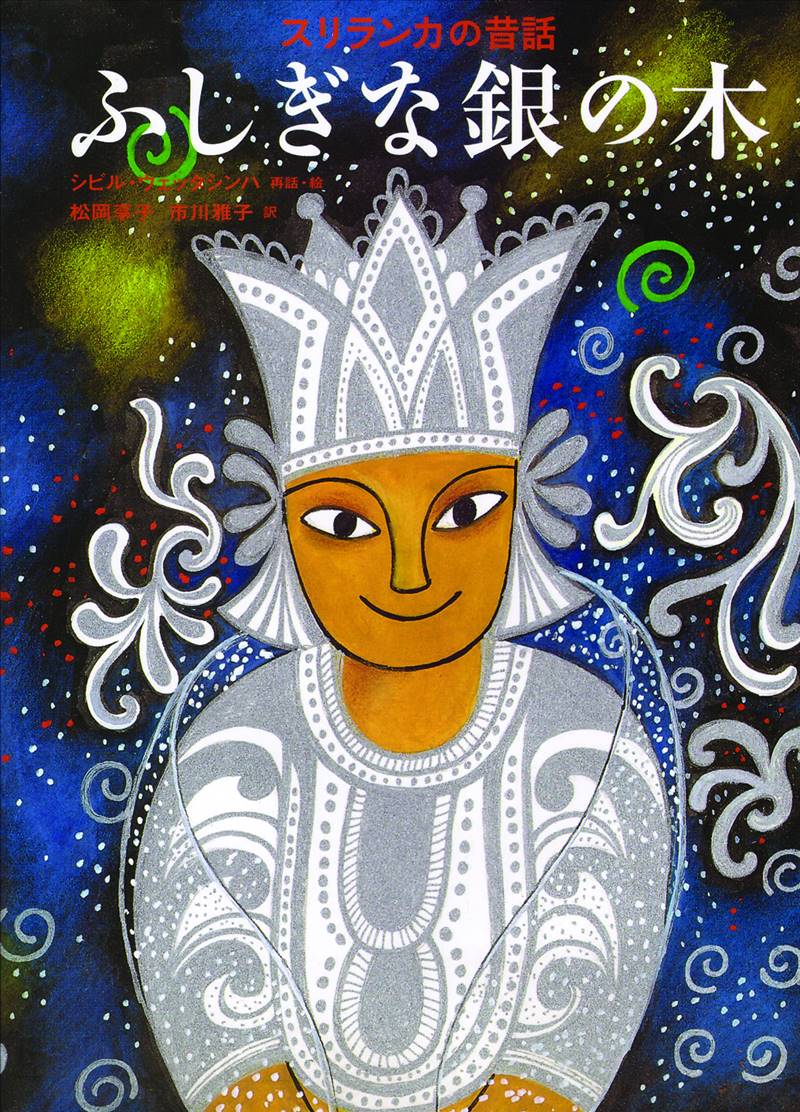

Among her more recent work, The Magic Silver Tree was well received in Japan. The illustrations from the story were a part of a popular exhibition of work in the country.

It took the efforts of a leading translator to get the stories of rural Sri Lanka to Japanese children. Kyoko Matsuoka (born in 1935) became friends with Wettasinghe in the early 1970s when they were both a part of the Asian Co-Publication Program. Matsuoka, who has been the director of the Tokyo Children’s Library translated The Child in Me, Podda and Poddi, Country Cat Visitors, Hoity the Fox and was a co-translator of The Magic Silver Tree.

“I enjoyed very much working with her books, as they are full of life… I have always been delighted in the sense of life and joy in Sybil’s picture books,” Matsuoka was cited as saying by The Nation in 2011. “I think every child, according to his/her nature would discover something he/she could treasure,” she added,

In 2012 Wettasinghe was awarded the Nikkei Asia Prize for Culture, recognising a lifetime of achievements.

Global impact

With her work being translated in Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, Dutch and other European languages, Wettasinghe was regularly invited for conferences and book exhibitions. She would fondly recall a productive period she spent in what was East Germany during the Cold War era.

What seemed to enamour Wettasinghe the most was the Buddhist pilgrimage in northern India and Nepal. She was able to undertake this pilgrimage on a few occasions and would recall to this writer of the feeling she’d have when she was in Sarnath, where the Buddha is believed to have given his first sermon. “I may have been an ant in a previous life listening to the sermon in Sarnath,” she said on more than one occasion.

As age began to catch up to Wettasinghe she would curtail and finally stop travelling abroad. She continued to work on her sketches in the study of her home in a leafy lane in the town of Nugegoda, just outside Colombo.

Wettasinghe would sit late in the evening listening to Pali chants and Buddhist sermons, while at the same time making sure that she was up well before the first rays of dawn shined on her home. Her daily ritual included feeding birds before she’d start writing and sketching.

In 2017, when she was invited by the Sri Lankan government to celebrate her 90th birthday, she’d recall how it was only such occasions that reminded her that she was actually old, while she still saw herself as a young girl, much like the girls who liked her stories.

In what would become her final major achievement, earlier this year, Wettasinghe, would connect with the children of Sri Lanka and set a Guinness World Record with the publication of her book Wonder Crystal. The book has 1,250 alternative endings. More than 20,000 children in Sri Lanka were invited to hone their imagination and suggest an ending for the book. It seems apt that a six and a half decade long writing career aimed at children was culminated with a world record that was made possible by the same audience Wettasinghe’s books were written for.

Her contributions to Sri Lankan literature were appreciated over the decades. These included the Vishwa Prasadini Award for Art and Children’s Literature, which was presented by Prime Minister

Sirimavo Bandaranaike in 1996 and in 2004, the Kala Keerthi, an national honour that is awarded for extraordinary achievements in the fine and performing arts.

In a condolence message on the day of her death, Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa said Wettasinghe “captured the hearts of children with her unique style of writing and helped develop the young minds.”

In 2017, the Sunday Times, Colombo called her “a grandmother to an entire nation of children.”

Wettasinghe wrote in her autobiography of spending her aging days placidly with a “mind as light as a feather” and no burdens. She ends the autobiography with this note: “When finally the day dawns for me to bid adieu I will be light hearted and free to begin my spiritual existence which will float smoothly with the whispering breezes and dwell on flower and fruit laden trees together with the singing birds and lilt on the gurgling brooks and rustling streams and meet the golden rays of the early morning sun at break of day, and finally float along with the fleecy white clouds in the vast blue skies on a long long peaceful journey in search of eternity.”

Ajay Kamalakaran is a journalist and writer based in Mumbai. He tweets @Ajaykamalakaran

Wettasinghe, who passed away in the early hours of the 1st of July, 2020, was a national icon in Sri Lanka, a symbol of the rapid strides in women’s empowerment the country made close on the heels of its independence. Born in the village of Gintota in the southern coast of what was then the British crown colony of Ceylon, her family, part of the early wave of rural to urban migration, moved to Colombo when she was a child.

In an autobiography of her childhood titled Eternally Yours, she gives us a rare glimpse of a life that is now unrecognizable in Colombo. Among the many vendors that would visit her home was the “bookman” who would carry a tall pile of books on his head visiting homes where there were children. “He could be called a walking library, for in his pile of books which he spread on our verandah floor were fantastic fairy tales,” she wrote. Her first introduction to children’s stories by Hans Christian Anderson was from this bookman. “I was fascinated with the pictures in these books that I yearned to read English,” Wettasinghe wrote.

Equally comfortable with writing in her native Sinhalese and English, The Umbrella Thief, which came out as a book in 1956, became one of the most read stories of all time on the island. The simple protagonist, Kiri Mama, who sees an umbrella for the first time when he visits Colombo from his village, and buys it and takes it home, is one of the most beloved characters in Sri Lankan literature.

Wettasinghe set a Guinness World Record with the publication of her book Wonder Crystal. The book has 1,250 alternative endings. More than 20,000 children in Sri Lanka were invited to hone their imagination and suggest an ending for the book

The Umbrella Thief, which Wettasinghe wrote for her “best fan and critic,” her husband Don Dharmapala (who would later head Sri Lankan media giant Lake House Publications), was a path-breaker in children’s literature in the country. At that time Sinhalese literature for children basically comprised of translation of European classics. The Umbrella Thief, with its illustrations managed to herald in a new era in children’s literature in the country. “Kuda Hora was the first Sinhalese book to completely marry words and pictures,” Sri Lankan playwright, journalist and poet Regi Siriwardena once remarked.

It was Wettasinghe’s ability to connect deeply with her village roots from an urban setting that made her work resonate widely with Sri Lankans of all backgrounds.

Religion and folklore

Hailing from a religious family, Wettasinghe incorporated Buddhist art and legends into her stories. Her 1965 story Vesak Lantern is also considered a timeless classic in Sri Lanka and other countries with a large Buddhist population.

The story is a nostalgic look at the excitement and preparation for the most important festival for the followers of the Buddha. The occasion was something that Wettasinghe looked forward to from her early childhood, and she shared vivid memories of her grandfather making his paper lanterns: “Coloured paper, scissors, cutters, rice paste and bamboo strips were scattered all over our floor during the preceding Vesak festival,” she wrote excitedly from her childhood.

The story Vesak Lantern propelled Wettasinghe to international fame, and it was awarded the Isabel Hutton Prize by the Women’s Council of England for Asian women writers in 1965. It was also featured in an anthology of Asian writing by UNESCO’s Asian Cultural Centre and in an anthology produced by the Pontificial Catholic University of Chile in 1998.

The Umbrella Thief and Vesak Lantern were both dramatized and adapted to children’s theatre.

Wettasinghe was also interested in the folklore and beliefs that predate and survived the Sinhalese community’s embracing of Buddhism. As a child, she heard many folktales from her Athamma (grandmother).

Her father had a friend who was an exorcist-cum-astrologer, who could perform ‘Kodivina’ or black magic to ward off evil eyes. She wrote about witnessing a “Mahanilanga Rakshya baliya”, an ancient devil dance to ward off evil spirits. The magic that was also so prevalent in her more than 200 stories was not of the dark kind.

Wettasinghe was also very familiar with Biblical stories as her primary education was at the Holy Family Convent in Colombo’s Bambalapitiya. In her autobiography she described her first encounter with a European nun, after gazing at a statue of Jesus Christ: “A rustle of beads, footsteps and the swish of a skirt fell on our ears. Instantly a strange looking fair person stood before us. Only her fair face and hands were visible, for she wore a long white gathered floor length skirt and on the top part of her body was a neck-hugging elbow length flared slip-on over a long sleeved blouse. Around her face was a pin frilled white bonnet, and the back of her head was covered with a black flimsy veil reaching down to her waist. A long bead chain dangled from her waistline with a silver cross at the end.” Wettasinghe, then six, froze, while her younger brother the wet the floor out of fear.

She would thrive in the cosmopolitan environment of the school and appreciate religious icons and paintings. Decades later, Wettasinghe would be invited to make illustrations for a Sinhalese edition of a children’s Bible (Deeptha Lama Maga). This was a task she took with the greatest care, especially when she had to illustrate the story of Adam and Eve. She won a special prize for those illustrations at the Biennial of Illustration Bratislava in 1989.

Success in Japan

Wettasinghe’s stories were well received in Japan. The Umbrella Thief (Kasadarobou in Japanese) was published in the country in 1982, when it became almost instantly famous by receiving an honourable mention at the third Noma Concours for Picture Book Illustrations. A few years later, it was voted the Japanese Library Association Award as the most popular children’s book.

Wettasinghe would make several trips to Japan for public exhibitions of her illustrations. Inspired by the aesthetic beauty of the country, her later artwork would have a clear hint of Aizuri-e or Japanese prints done in shades of blue.

Among her more recent work, The Magic Silver Tree was well received in Japan. The illustrations from the story were a part of a popular exhibition of work in the country.

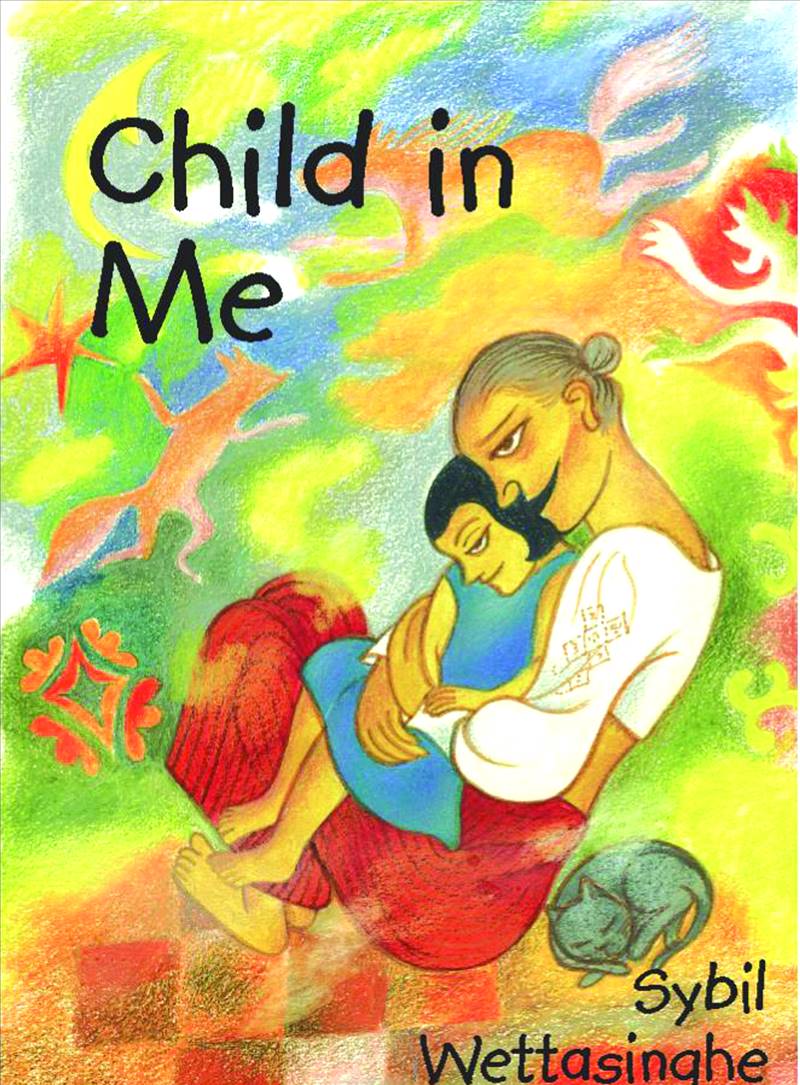

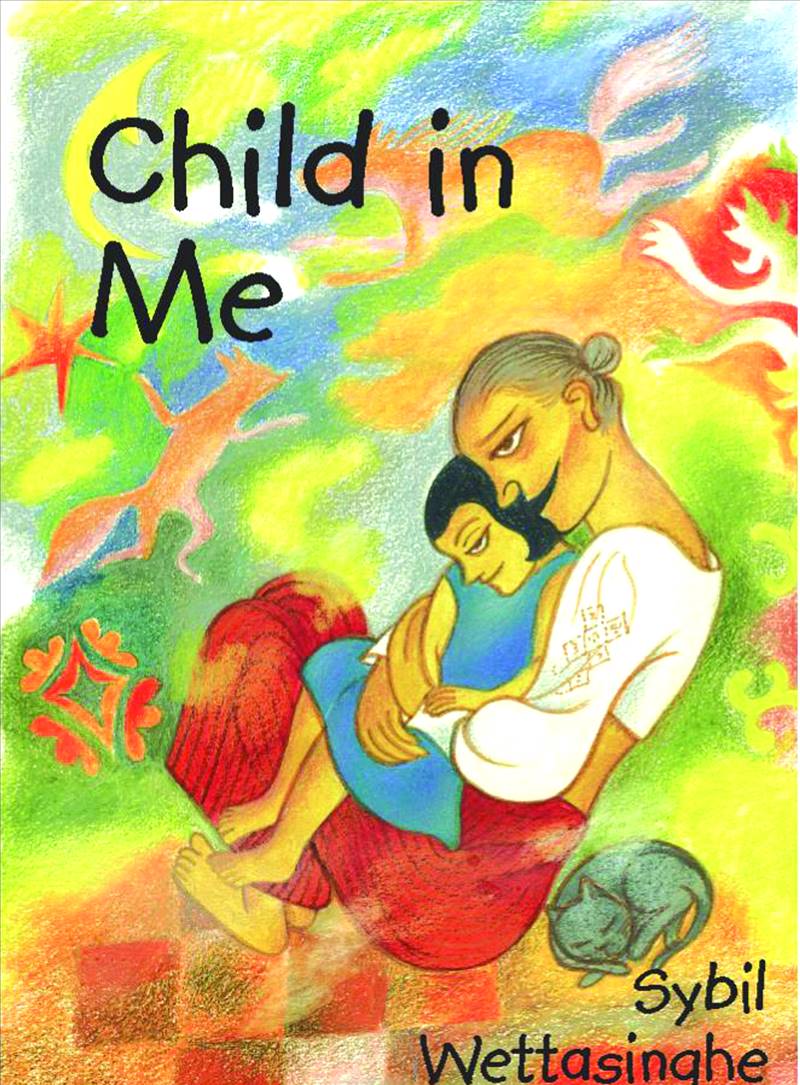

It took the efforts of a leading translator to get the stories of rural Sri Lanka to Japanese children. Kyoko Matsuoka (born in 1935) became friends with Wettasinghe in the early 1970s when they were both a part of the Asian Co-Publication Program. Matsuoka, who has been the director of the Tokyo Children’s Library translated The Child in Me, Podda and Poddi, Country Cat Visitors, Hoity the Fox and was a co-translator of The Magic Silver Tree.

“I enjoyed very much working with her books, as they are full of life… I have always been delighted in the sense of life and joy in Sybil’s picture books,” Matsuoka was cited as saying by The Nation in 2011. “I think every child, according to his/her nature would discover something he/she could treasure,” she added,

In 2012 Wettasinghe was awarded the Nikkei Asia Prize for Culture, recognising a lifetime of achievements.

Her 1965 story Vesak Lantern is also considered a timeless classic in Sri Lanka and other countries with a large Buddhist population

Global impact

With her work being translated in Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, Dutch and other European languages, Wettasinghe was regularly invited for conferences and book exhibitions. She would fondly recall a productive period she spent in what was East Germany during the Cold War era.

What seemed to enamour Wettasinghe the most was the Buddhist pilgrimage in northern India and Nepal. She was able to undertake this pilgrimage on a few occasions and would recall to this writer of the feeling she’d have when she was in Sarnath, where the Buddha is believed to have given his first sermon. “I may have been an ant in a previous life listening to the sermon in Sarnath,” she said on more than one occasion.

As age began to catch up to Wettasinghe she would curtail and finally stop travelling abroad. She continued to work on her sketches in the study of her home in a leafy lane in the town of Nugegoda, just outside Colombo.

Wettasinghe would sit late in the evening listening to Pali chants and Buddhist sermons, while at the same time making sure that she was up well before the first rays of dawn shined on her home. Her daily ritual included feeding birds before she’d start writing and sketching.

In 2017, when she was invited by the Sri Lankan government to celebrate her 90th birthday, she’d recall how it was only such occasions that reminded her that she was actually old, while she still saw herself as a young girl, much like the girls who liked her stories.

In what would become her final major achievement, earlier this year, Wettasinghe, would connect with the children of Sri Lanka and set a Guinness World Record with the publication of her book Wonder Crystal. The book has 1,250 alternative endings. More than 20,000 children in Sri Lanka were invited to hone their imagination and suggest an ending for the book. It seems apt that a six and a half decade long writing career aimed at children was culminated with a world record that was made possible by the same audience Wettasinghe’s books were written for.

Her contributions to Sri Lankan literature were appreciated over the decades. These included the Vishwa Prasadini Award for Art and Children’s Literature, which was presented by Prime Minister

Sirimavo Bandaranaike in 1996 and in 2004, the Kala Keerthi, an national honour that is awarded for extraordinary achievements in the fine and performing arts.

In a condolence message on the day of her death, Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa said Wettasinghe “captured the hearts of children with her unique style of writing and helped develop the young minds.”

In 2017, the Sunday Times, Colombo called her “a grandmother to an entire nation of children.”

Wettasinghe wrote in her autobiography of spending her aging days placidly with a “mind as light as a feather” and no burdens. She ends the autobiography with this note: “When finally the day dawns for me to bid adieu I will be light hearted and free to begin my spiritual existence which will float smoothly with the whispering breezes and dwell on flower and fruit laden trees together with the singing birds and lilt on the gurgling brooks and rustling streams and meet the golden rays of the early morning sun at break of day, and finally float along with the fleecy white clouds in the vast blue skies on a long long peaceful journey in search of eternity.”

Ajay Kamalakaran is a journalist and writer based in Mumbai. He tweets @Ajaykamalakaran