On Wednesday, the government laid before the Senate the ICJ (Review and Reconsideration) Ordinance 2020 to implement the ICJ verdict in the case of Indian spy Kulbhushan Jadhav sentenced to death by a military court four years ago for spying and fomenting terrorism in Pakistan. Two days earlier, it had been presented in the National Assembly as well. The ICJ verdict called for providing consular access to Jadhav and asked Pakistan to provide for right to appeal to the spy by enacting appropriate legislation.

Also on Wednesday, the foreign minister stated in the National Assembly that the ordinance was not Jadhav specific and it would also be applicable to similar cases in the future. He claimed that India wanted to drag Pakistan again to the ICJ but by following the ICJ instructions the Indian attempt had been foiled.

There is a window of opportunity.

That Pakistan must implement the ICJ verdict is not in the doubt. The government says it is to ward off Indian plans. The opposition has not opposed it. No opposition political party has opposed the implementation of ICJ verdict.

Also, not many believe that the military court’s sentence will be implemented and Jadhav actually hanged. When the US ambassador in Islamabad walked into the GHQ soon after the sentencing in April 2017, it was clear that carrying out the death sentence will not be easy. This perception is also reinforced by the mysterious silence of the extremist groups known to be in the good books of the military on the issue. They are not on the roads demanding Jadhav be hanged.

So what is the issue and why did the government promulgate the ordinance secretly without taking the opposition into confidence in May last?

The law minister says that the constitution does not require consultation with the opposition on the promulgation of an ordinance. This is not enough. Leave aside consultations with the opposition, why was it not laid in the parliament as required under the constitution, even when sessions of both the Senate and National Assembly were held after its promulgation?

Jadhav had already filed a mercy petition to the army chief and it provided a viable course for ‘effective reconsideration’ of the verdict as demanded by the ICJ. If hanging Jadhav was difficult, a decision by GHQ on the mercy decision was also not easy. Who would want to face the “Modi ka yaar” mantra? So the decision was taken to adopt the ordinance route. Fair enough, but why keep the ordinance a secret and not put before the parliament in the constitutionally stipulated period?

The ordinance enabled Jadhav or the Indian consulate to file a review petition before the Islamabad High Court within 60 days. It was hoped that in the event of a positive outcome of appeal, Jadhav would be set free even before the issue came up before the parliament. But things went awry when Jadhav refused to file review petition during the 60 day period and insisted that his mercy petition before the army chief be decided and laying of the ordinance in parliament could no longer be delayed.

This begs the question why a parliamentary debate is so dreaded?

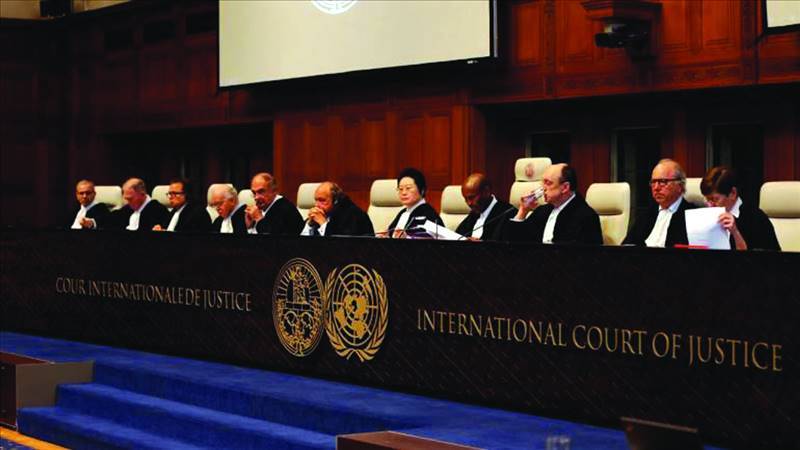

The ICJ verdict not only called upon Pakistan to provide “effective review and reconsideration” of Jadhav’s conviction and sentencing, it also laid down certain parameters for it.

The military courts and their verdicts under the Army Act are a parallel judicial system with scant respect for principles of a fair trial, due process, right of defence of the accused, right to engage a counsel of choice and mechanism for evidence gathering and evidence valuation. Their verdicts are not challengeable before courts.

However, through judicial verdicts the courts have assumed a limited jurisdiction of review. Under this extremely limited jurisdiction, the courts are still barred from re-examining every piece of evidence on the basis of which a military court has pronounced verdict. The courts are also barred from going into “controversial questions of facts” whatever it means in hearing appeals against military courts’ verdicts.

The ICJ verdict had thus opened the doors for reform of Pakistan’s notoriously flawed military justice system. This was anathema to some elements in the establishment, hence the need to keep the parliament and political parties out of the loop.

The ordinance now placed before both the houses of parliament must be debated threadbare in the light of ICJ verdict. It is a God sent opportunity to the parliament to critically examine the military justice system and make improvements in it.

The debate in the parliament should also provide an occasion to ponder over the mysterious cycle of acrimony between India and Pakistan.

For instance, the current animosity can be traced back to the dramatic visit by Prime Minister Modi to Lahore to attend the wedding of Nawaz Sharif’s granddaughter on the eve of Christmas in 2015. Within a week of Modi’s diplomatic leap, the Pathankot attack incident took place, pushing back prospects of any normalization.

In 1998, Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s visit to Lahore was similarly followed by the Kargil misadventure that brought the two countries to the brink of war.

In November 2008, President Zardari’s offer for talks on no first use of nuclear weapons was thwarted by the Mumbai attack within days of the offer.

Kulbhushan is unlikely to be hanged. Meanwhile, the parliament has an historic opportunity to revisit the military’s justice system and also debate the mysterious cycle of acrimony in relations between the two nuclear armed neighbours.

The writer is a former senator

Also on Wednesday, the foreign minister stated in the National Assembly that the ordinance was not Jadhav specific and it would also be applicable to similar cases in the future. He claimed that India wanted to drag Pakistan again to the ICJ but by following the ICJ instructions the Indian attempt had been foiled.

There is a window of opportunity.

That Pakistan must implement the ICJ verdict is not in the doubt. The government says it is to ward off Indian plans. The opposition has not opposed it. No opposition political party has opposed the implementation of ICJ verdict.

Also, not many believe that the military court’s sentence will be implemented and Jadhav actually hanged. When the US ambassador in Islamabad walked into the GHQ soon after the sentencing in April 2017, it was clear that carrying out the death sentence will not be easy. This perception is also reinforced by the mysterious silence of the extremist groups known to be in the good books of the military on the issue. They are not on the roads demanding Jadhav be hanged.

The ICJ verdict has opened the doors for reform of Pakistan’s notoriously flawed military justice system

So what is the issue and why did the government promulgate the ordinance secretly without taking the opposition into confidence in May last?

The law minister says that the constitution does not require consultation with the opposition on the promulgation of an ordinance. This is not enough. Leave aside consultations with the opposition, why was it not laid in the parliament as required under the constitution, even when sessions of both the Senate and National Assembly were held after its promulgation?

Jadhav had already filed a mercy petition to the army chief and it provided a viable course for ‘effective reconsideration’ of the verdict as demanded by the ICJ. If hanging Jadhav was difficult, a decision by GHQ on the mercy decision was also not easy. Who would want to face the “Modi ka yaar” mantra? So the decision was taken to adopt the ordinance route. Fair enough, but why keep the ordinance a secret and not put before the parliament in the constitutionally stipulated period?

The ordinance enabled Jadhav or the Indian consulate to file a review petition before the Islamabad High Court within 60 days. It was hoped that in the event of a positive outcome of appeal, Jadhav would be set free even before the issue came up before the parliament. But things went awry when Jadhav refused to file review petition during the 60 day period and insisted that his mercy petition before the army chief be decided and laying of the ordinance in parliament could no longer be delayed.

This begs the question why a parliamentary debate is so dreaded?

The ICJ verdict not only called upon Pakistan to provide “effective review and reconsideration” of Jadhav’s conviction and sentencing, it also laid down certain parameters for it.

The military courts and their verdicts under the Army Act are a parallel judicial system with scant respect for principles of a fair trial, due process, right of defence of the accused, right to engage a counsel of choice and mechanism for evidence gathering and evidence valuation. Their verdicts are not challengeable before courts.

However, through judicial verdicts the courts have assumed a limited jurisdiction of review. Under this extremely limited jurisdiction, the courts are still barred from re-examining every piece of evidence on the basis of which a military court has pronounced verdict. The courts are also barred from going into “controversial questions of facts” whatever it means in hearing appeals against military courts’ verdicts.

The ICJ verdict had thus opened the doors for reform of Pakistan’s notoriously flawed military justice system. This was anathema to some elements in the establishment, hence the need to keep the parliament and political parties out of the loop.

The ordinance now placed before both the houses of parliament must be debated threadbare in the light of ICJ verdict. It is a God sent opportunity to the parliament to critically examine the military justice system and make improvements in it.

The debate in the parliament should also provide an occasion to ponder over the mysterious cycle of acrimony between India and Pakistan.

For instance, the current animosity can be traced back to the dramatic visit by Prime Minister Modi to Lahore to attend the wedding of Nawaz Sharif’s granddaughter on the eve of Christmas in 2015. Within a week of Modi’s diplomatic leap, the Pathankot attack incident took place, pushing back prospects of any normalization.

In 1998, Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s visit to Lahore was similarly followed by the Kargil misadventure that brought the two countries to the brink of war.

In November 2008, President Zardari’s offer for talks on no first use of nuclear weapons was thwarted by the Mumbai attack within days of the offer.

Kulbhushan is unlikely to be hanged. Meanwhile, the parliament has an historic opportunity to revisit the military’s justice system and also debate the mysterious cycle of acrimony in relations between the two nuclear armed neighbours.

The writer is a former senator