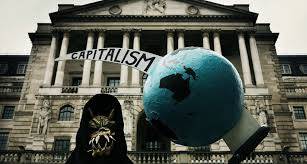

The long term future of capitalism

Looking at the history of the world over the last millennium, the phenomenon of modern capitalism only began with the Industrial Revolution in Britain in 1750. The appearance of nation States and the beginning of significant trade and allied commercial exchanges between them occurred about a hundred years earlier following the Conference of Westphalia in 1648. So, in a sense, the nation State, industrialization and commercial links between nation States were roughly contemporaneous phenomena that have been dominant features of the global economy only for about 300 plus years. Given that human society has passed through an extraordinary array of civilisational, cultural and organizational forms, domestic, regional and global power structures, rivalries, and wars between nation States over the last 300 years, the current state of affairs can by no means be described as the culmination of all human economic and social development.

Nor, for that matter, can the years beginning with the new millennium be described as the end-point of human understanding towards a better, more inclusive and more prosperous world. Notwithstanding major programmes of legal, economic and social reform, the extension of the electoral suffrage and the creation of the welfare State, we cannot thereby conclude that what human society has achieved today is as good as it is going to get for the vast majority of mankind, save occasional piecemeal ‘sticking plaster’ actions and half-hearted solutions to correct glaring economic and social shortcomings. In fact, even such actions take place only in response to a crisis. It is a standard, somewhat fatuous, cliché uttered by many, usually by politicians hoping to get re-elected, that ‘much remains to be done’. Yes, much will always remain to be done in all societies in that since human beings have themselves been instrumental in creating the problems in the first place it is they who will have to find the solutions to these problems and to many others that will surely follow if nothing is done.

In that regard, whether it is endemic global poverty, the absence of distributional justice internationally or within nations, or the looming challenges of global warming and environmental destruction – all are inter-linked – these challenges will first have to be genuinely accepted as real by the governing elites everywhere if the world is going to tackle them effectively. Thus far, there is an unmistakable tendency within the global fraternity of elites either to deny completely the existence of such problems or, as in the case of global warming, to minimize its likely adverse impact (Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin 2020). It is also the case that capitalism both provides and also takes away. Who can deny that for the majority of people in most capitalist economies, especially the poor, the constantly advertised pleasures of consumer choice in the media have always been tantalizingly out of reach as they struggle with precarious jobs, wildly expensive housing, shrinking public services and diminishing social protection.

Even the most incorrigible apologists for the current state of affairs will have to concede that endlessly patching up a system that has produced one crisis after another and has then only produced solutions in which the first priority is to leave the status quo untouched, is to accept defeat in all but name. Both history and common sense tell us that while the ‘greatest good of the greatest number’ has been the apparent driving force of change during the last 150 years, except for rare experiences, such as the post-World War II consensus that established the welfare State, it is always the rich and powerful ruling elites that have fared best. The reality is that, far from declaring victory in 1991, much of the capitalist world even today has only scratched the surface towards redressing the huge moral and material losses of unfulfilled human potential that it has itself generated over its chequered history.

When we look at capitalism over the last 300 years in its various guises we see the many technological breakthroughs in the 18th and 19th centuries that enabled the countries where these were made to take a huge leap from the low output, quasi-stability of feudalism to significant material abundance. The overall picture, however, is far less clear. In this picture, side-by-side with material abundance, widespread poverty, malnutrition, disease and the growth of slums that unchecked urbanization brought in its wake have persisted. In the 19th century the conquest of faraway militarily weaker peoples and their territories and in the enslavement of millions of others as dominant European powers sought to extend their spheres of influence and control in order to make capitalism more efficient by converting all human labour into a commodity was one of its essential features. The result was the emergence of huge economic and social disparities between and within countries, the relentless growth of national rivalries for resources and markets that led to unimaginable suffering in the form of two world wars in the 20th century, and of unending local and regional wars in the 21st century. But, most of all, unrestrained profit-maximising behaviour has resulted in the willful destruction of the earth’s physical ability to sustain the lives of those who live on it. Climate change and environmental destruction cannot simply be wished away by the proponents of capitalism.

Today, it is true that, in discussing the central thesis of this paper, namely, the phenomenon of capitalism evolving from competition to monopolization and then to rent-seeking, it must be conceded that it does not apply equally to all developed countries. For instance, Germany in Europe, the much smaller Scandinavian economies and Japan in East Asia still appear to be following a different trajectory with a somewhat greater stress on the benefits of equity and this may allow them, the rightward lurch in global politics permitting, to avoid the pattern of evolution that the UK economy has fallen prey to since 1980. But here, too, the challenges of growing inequality, pressure on the delivery of public goods and tackling climate change continue to remain mired in unending debates with real solutions as far away as ever.

So, what clues does the evolution of the UK economy provide about the future evolution of capitalism at a systemic level? Over the short term, say, the next 10-15 years, the role of massive corporations will almost certainly remain dominant in the global economy with State authority playing a subsidiary role. This Marx called the centralization or concentration of capital, all done in order to maximize monopoly profits. This is visible right across the world. Furthermore, the process of monopolization is being accompanied by ‘promoter’s profits’ whereby mergers, acquisitions and IPOs provide huge rewards to the financial sector, on the one hand, and intensify the ‘winner takes all’ phenomenon for the promoters, on the other. Who can deny that the resultant monopoly corporations have greatly exacerbated inequality in all societies, including during the Covid 19 pandemic, and strengthened class-based political structures in favour of the ruling elite in most capitalist economies.

Marx had noted that social stratification is the product of historical development and the State is an instrument in the hands of the ruling elite for enforcing and guaranteeing the stability of the class structure itself primarily by ensuring property rights. Engels explained that the highest purpose of the State was the protection of private property (Joan Robinson 1966). Today, capitalist private property does not consist primarily of physical things; it extends to stocks, shares, patents, trademarks, patents and platforms. Indeed, it extends, perhaps most of all in the UK to the output of the creative industries where it can foster an overall climate of opinion for the whole of society and in this respect the ruling elite in the UK are very much in the driving seat with their cheer leaders and hangers-on in the media. Study after study shows that the proceeds of economic growth in most capitalist economies now accrue to the richest 10 per cent and average real wages for the bottom 40 per cent have simply stopped rising since the beginning of the millennium with scarcely a raised eyebrow. More alarmingly, in the developed world as a whole, apart from some left-leaning academics and think tanks, no one is particularly concerned over these trends. This model of capitalism may not have been the result of any conscious plan on the part of the ruling elites of most countries. But, neither can it be put down to the inexorable working of any mysterious external disembodied forces. However, no one in the UK or elsewhere is willing to talk about its real cause: abject political failure.

Looking at the history of the world over the last millennium, the phenomenon of modern capitalism only began with the Industrial Revolution in Britain in 1750. The appearance of nation States and the beginning of significant trade and allied commercial exchanges between them occurred about a hundred years earlier following the Conference of Westphalia in 1648. So, in a sense, the nation State, industrialization and commercial links between nation States were roughly contemporaneous phenomena that have been dominant features of the global economy only for about 300 plus years. Given that human society has passed through an extraordinary array of civilisational, cultural and organizational forms, domestic, regional and global power structures, rivalries, and wars between nation States over the last 300 years, the current state of affairs can by no means be described as the culmination of all human economic and social development.

Nor, for that matter, can the years beginning with the new millennium be described as the end-point of human understanding towards a better, more inclusive and more prosperous world. Notwithstanding major programmes of legal, economic and social reform, the extension of the electoral suffrage and the creation of the welfare State, we cannot thereby conclude that what human society has achieved today is as good as it is going to get for the vast majority of mankind, save occasional piecemeal ‘sticking plaster’ actions and half-hearted solutions to correct glaring economic and social shortcomings. In fact, even such actions take place only in response to a crisis. It is a standard, somewhat fatuous, cliché uttered by many, usually by politicians hoping to get re-elected, that ‘much remains to be done’. Yes, much will always remain to be done in all societies in that since human beings have themselves been instrumental in creating the problems in the first place it is they who will have to find the solutions to these problems and to many others that will surely follow if nothing is done.

In that regard, whether it is endemic global poverty, the absence of distributional justice internationally or within nations, or the looming challenges of global warming and environmental destruction – all are inter-linked – these challenges will first have to be genuinely accepted as real by the governing elites everywhere if the world is going to tackle them effectively. Thus far, there is an unmistakable tendency within the global fraternity of elites either to deny completely the existence of such problems or, as in the case of global warming, to minimize its likely adverse impact (Noam Chomsky and Robert Pollin 2020). It is also the case that capitalism both provides and also takes away. Who can deny that for the majority of people in most capitalist economies, especially the poor, the constantly advertised pleasures of consumer choice in the media have always been tantalizingly out of reach as they struggle with precarious jobs, wildly expensive housing, shrinking public services and diminishing social protection.

Even the most incorrigible apologists for the current state of affairs will have to concede that endlessly patching up a system that has produced one crisis after another and has then only produced solutions in which the first priority is to leave the status quo untouched, is to accept defeat in all but name. Both history and common sense tell us that while the ‘greatest good of the greatest number’ has been the apparent driving force of change during the last 150 years, except for rare experiences, such as the post-World War II consensus that established the welfare State, it is always the rich and powerful ruling elites that have fared best. The reality is that, far from declaring victory in 1991, much of the capitalist world even today has only scratched the surface towards redressing the huge moral and material losses of unfulfilled human potential that it has itself generated over its chequered history.

When we look at capitalism over the last 300 years in its various guises we see the many technological breakthroughs in the 18th and 19th centuries that enabled the countries where these were made to take a huge leap from the low output, quasi-stability of feudalism to significant material abundance. The overall picture, however, is far less clear. In this picture, side-by-side with material abundance, widespread poverty, malnutrition, disease and the growth of slums that unchecked urbanization brought in its wake have persisted. In the 19th century the conquest of faraway militarily weaker peoples and their territories and in the enslavement of millions of others as dominant European powers sought to extend their spheres of influence and control in order to make capitalism more efficient by converting all human labour into a commodity was one of its essential features. The result was the emergence of huge economic and social disparities between and within countries, the relentless growth of national rivalries for resources and markets that led to unimaginable suffering in the form of two world wars in the 20th century, and of unending local and regional wars in the 21st century. But, most of all, unrestrained profit-maximising behaviour has resulted in the willful destruction of the earth’s physical ability to sustain the lives of those who live on it. Climate change and environmental destruction cannot simply be wished away by the proponents of capitalism.

Today, it is true that, in discussing the central thesis of this paper, namely, the phenomenon of capitalism evolving from competition to monopolization and then to rent-seeking, it must be conceded that it does not apply equally to all developed countries. For instance, Germany in Europe, the much smaller Scandinavian economies and Japan in East Asia still appear to be following a different trajectory with a somewhat greater stress on the benefits of equity and this may allow them, the rightward lurch in global politics permitting, to avoid the pattern of evolution that the UK economy has fallen prey to since 1980. But here, too, the challenges of growing inequality, pressure on the delivery of public goods and tackling climate change continue to remain mired in unending debates with real solutions as far away as ever.

So, what clues does the evolution of the UK economy provide about the future evolution of capitalism at a systemic level? Over the short term, say, the next 10-15 years, the role of massive corporations will almost certainly remain dominant in the global economy with State authority playing a subsidiary role. This Marx called the centralization or concentration of capital, all done in order to maximize monopoly profits. This is visible right across the world. Furthermore, the process of monopolization is being accompanied by ‘promoter’s profits’ whereby mergers, acquisitions and IPOs provide huge rewards to the financial sector, on the one hand, and intensify the ‘winner takes all’ phenomenon for the promoters, on the other. Who can deny that the resultant monopoly corporations have greatly exacerbated inequality in all societies, including during the Covid 19 pandemic, and strengthened class-based political structures in favour of the ruling elite in most capitalist economies.

Marx had noted that social stratification is the product of historical development and the State is an instrument in the hands of the ruling elite for enforcing and guaranteeing the stability of the class structure itself primarily by ensuring property rights. Engels explained that the highest purpose of the State was the protection of private property (Joan Robinson 1966). Today, capitalist private property does not consist primarily of physical things; it extends to stocks, shares, patents, trademarks, patents and platforms. Indeed, it extends, perhaps most of all in the UK to the output of the creative industries where it can foster an overall climate of opinion for the whole of society and in this respect the ruling elite in the UK are very much in the driving seat with their cheer leaders and hangers-on in the media. Study after study shows that the proceeds of economic growth in most capitalist economies now accrue to the richest 10 per cent and average real wages for the bottom 40 per cent have simply stopped rising since the beginning of the millennium with scarcely a raised eyebrow. More alarmingly, in the developed world as a whole, apart from some left-leaning academics and think tanks, no one is particularly concerned over these trends. This model of capitalism may not have been the result of any conscious plan on the part of the ruling elites of most countries. But, neither can it be put down to the inexorable working of any mysterious external disembodied forces. However, no one in the UK or elsewhere is willing to talk about its real cause: abject political failure.