“Elite Pakistan school turns prison for principal barred from doing his job” is a newspaper headline. And, yes, it is about Aitchison College and about its Principal. Yet, it is not today’s headline. It appeared nearly a decade ago, on 1st October 2015 to be precise. But, although it concerned an elite school in Pakistan, it did not appear in any Pakistani newspaper: it appeared in The Guardian.

However, before we proceed with this sorry tale, readers are invited to look up this link on the internet. That story is still there on The Guardian’s website. That is what makes this recall all the more propitious —-partly because Michael Thompson’s present difficulty can be likened to that of his predecessor, although, as a foreigner, he has been treated with our customary kindness when compared with the brutality of the treatment accorded 9 years ago to his predecessor, who was after all only a native. His name was Professor Dr. Agha Ghazanfar.

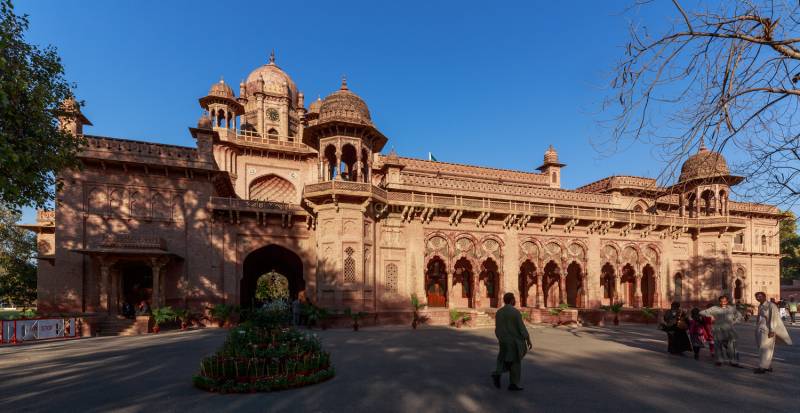

The more important, and timely, reason for the present recollection is that, when The Guardian was asked why they, an international paper of global distinction, had chosen to highlight what was merely a Pakistan school official’s internal squabble with its governing body, their reply was to quote the words of that ousted Principal (Ghazanfar) when he described his school as “like a microcosm of the country as a whole... that is rife with corruption, mismanagement and nepotism.” They said that they had been struck by the truism of that pithy encapsulation that Aitchison was verily a microcosm of Pakistan as a whole, especially its corruption, deceit, mismanagement, incompetence and vice-like control by a ruling elite that had transformed into a crime syndicate.

However, getting back to the storyline - Michael Thompson’s predecessor did not get to complete that “prisoner’s diary” that is mentioned in The Guardian story’s headline, because a fortnight later, he was physically removed from College premises. He chose self-exile in England, where he has lived the past 8 years in anonymity, in preference to the country of his birth, which he had served all his life.

While Michael’s exit is an honourable one, Ghazanfar’s was draconian and “without cause,” as the Board of Directors acknowledges and admitted as such to The Guardian – not wishing the public to see Aitchison’s “dirty linen,” as Khwaja Tariq Rahim is quoted to have said to that newspaper on behalf of the Board.

Readers are invited to draw their own comparisons, parallels and contrasts between the current story of Michael Thompson, the ongoing Aitchison saga, and the tale of his predecessor. History is indeed repeating itself, as it always does in Pakistan. I do not doubt that this unrest in front of the Governor’s House will soon die down; it always does. Status quo ante will prevail, even if Michael is persuaded once again, as he often has been in the past, to withdraw his resignation. Or, some face-saving device will be found very soon – it always is — and the venerable Syed Babar Ali will find a way to honour Michael’s memory, for he has, after all, done some commendable work for the College in the 8 years of his reputedly excellent stewardship of it. By contrast, Ghazanfar was not allowed even 8 months.

Here the similarity between the two cases ends. While Michael’s exit is an honourable one, Ghazanfar’s was draconian and “without cause,” as the Board of Directors acknowledges and admitted as such to The Guardian – not wishing the public to see Aitchison’s “dirty linen,” as Khwaja Tariq Rahim is quoted to have said to that newspaper on behalf of the Board. The second major difference is that Michael, an Australian school administrator of undoubted — and now proven– calibre was called upon, in continuation of a historic Aitchisonian tradition of imperial importation from 1886 onwards, to burnish its elitist image as the South Asian Eton. He was not required to cleanse its Augean stables. He succeeded quite spectacularly in his assigned task, which is why accolades are rightly being showered upon him by parents and Old Aitchisonians, including Babar Ali and myself, alike. A contributory, and perhaps not insignificant, factor is our historic and racial obeisance to Western authority and epidermis.

By contrast, Ghazanfar was homegrown and an Old Boy to boot: he had himself studied at Aitchison for 11 years from 1952 to 1961 and was thus privy to much of the school’s dirty linen. He may not have tried to wash it in public, but it came out nonetheless because he set out on a characteristically most un-Aitchisonian mission. He tried to break the elite consensus which is the bedrock of this institution. The Guardian story and a few other media outlets testified to that.

But, Ghazanfar’s case was different in yet another way. Michael Thompson would simply go away, back to his home country (Australia) and be remembered fondly thereafter, without subsequent angst – since he was after all an outsider and a very well-meaning and conscientious foreigner. But what do you do with an Insider who is bringing down the walls of your own Jericho?

Here Ghazanfar’s trajectory becomes very different from that of Michael Thompson. Michael’s story ends (or will end) with his departure from Aitchison. Ghazanfar’s begins with his ousting.

The Principal of that time, who happens to be the present author, never challenged the administrative authority of the Board of Directors or of the Governor. He merely sought a juridical opinion on the vires of one particular judicial order, and it was the Judiciary, not the Board or the Governor, that wouldn’t give an answer.

The present case of Michael Thompson’s resignation is one of administrative malfeasance. It is one of a political institutional tussle between privileged groups. On one side stands the political overlordship of a Party that has wielded political authority in Punjab since 1986 and one that has its own Prime Minister, Chief Minister and governor, and hence a claim to the fruits of Aitchison. On the other side is the Old Guard, which is a much older elite that also controls the rest of the private educational mafia of Lahore that is embedded in the upper tiers of the lucrative education business. The Old Guard’s interface with the parvenu political establishment is often not direct. In this case, it is an arms-length transaction carried out through professional management. When that management tries to exert its authority, especially when it is a foreign management, such as that of Michael Thompson, conflict is inevitable. This conflict is never in the public interest: it is always one of competing private interests. That is why it is always resolved through a bit of give and take, as this one will be.

By contrast, the 2015 conflict was of a different genre altogether. It was the epitome not of any administrative malfeasance, political interference (or otherwise), personality clash, misunderstanding or anything of that sort. Rather, it was the manifestation of a fractured judiciary and a dysfunctional State - which has nothing whatever to do with how well (or otherwise) a government machinery or a public educational institution runs or should run.

The Principal of that time, who happens to be the present author, never challenged the administrative authority of the Board of Directors or of the Governor. He merely sought a juridical opinion on the vires of one particular judicial order, and it was the Judiciary, not the Board or the Governor, that wouldn’t give an answer.

The essence of the two cases is also entirely different because the collisions in the two cases are between very different competing class interests. The present conflict is superficial and will be resolved soon, as it is simply between two officials of government and public institutions. But the 2015 collision was with the financial and political clout of a business class that is more permanently entrenched, not only in the microcosm of the school, but also in Pakistani society as a whole. That is why those conflicts could never be resolved because the interests upon which they are based are perhaps irreconcilable.