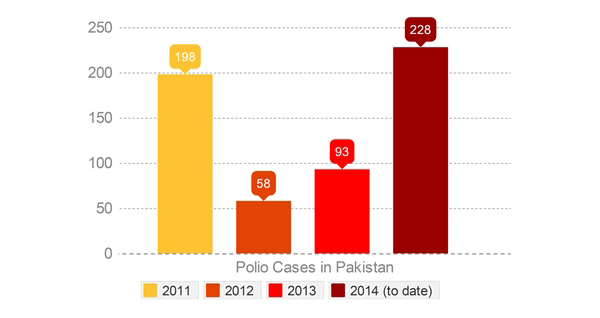

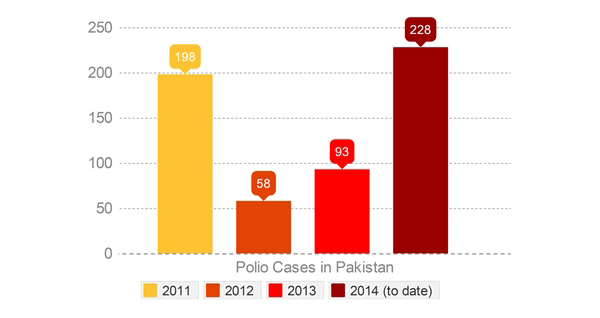

Pakistan is the last country in the world where polio continues to spread at an alarming rate. The other two countries, Nigeria and Afghanistan, have seen six and twelve cases in 2014 respectively, lower than their cumulative count for 2013. Pakistan saw 93 cases in 2013, which was a marked increase over the 58 cases in 2012. In October, a full two months before the year’s end, Pakistan has already recorded 228 cases of polio in the country, the highest in 14 years. Dr Elias Durry, the World Health Organization (WHO) appointed top polio specialist in the country says there is a realistic chance that in 2015, Pakistan might be the only affected country in the world.

It is a matter of great national embarrassment that well over 90% of the cases reported worldwide in 2014 are reported from Pakistan.

All of this is not to say that Pakistan has made no progress in the two decades long fight against the disease. In 1994, the country recorded 25,000 cases. The 228 cases today are less than a percent of that. But contextually, Pakistan has lost significant traction, as the lowest number of cases (28), was reported in 2005, nine years ago. Despite incredible progress, and an expanded immunization program that operates with the help of a network of nearly 200,000 workers to help vaccinate 33.4 million children under the age of five in over 100 districts simultaneously, Pakistan seems to have taken several steps back. It is a massive undertaking, one that requires a colossal amount of coordination, transparency and ownership for it to work properly.

This coordination, transparency, and ownership of the government is severely lacking, according to the International Monitoring Board’s (IMB) chairman Dr Liam Dolandson. The IMB’s damning report called the polio eradication program a disaster which should not be allowed to continue even another month. The accompanying letter demanded “nothing short of transformative action”, and that the eradication program should be handed over to the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA). Saira Afzal Tarrar, Minister of State for National Health Services, Regulation and Coordination (NHSRC) has already stated that the NDMA is short-staffed and lacks the capacity to deal with this challenge. The NDMA spokesperson mirrors these sentiments, stating that the NDMA is willing to take on the challenge, but needs to be properly equipped to meet it.

The second big problem, often admitted by officials, and alluded to by experts, are the security-compromised areas in the country. In January 2014, Peshawar, capital of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province, was declared the largest polio reservoir in the world by the WHO. The latest seven polio cases, reported on October 28, 2014 came from KP and the adjoining Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). A Taliban-enforced ban has kept polio vaccination teams at bay in certain areas of FATA since June 2012.

[quote]They have been led to believe the campaign is a conspiracy[/quote]

Other problems include a small number of families who also refuse vaccinations, either out of fear of militant backlash, or because they have been led to believe the campaign is a conspiracy. Additionally, 60 polio workers have been killed since December 2012 in militant attacks, affecting vaccination campaigns in certain parts of the country.

On June 15, 2014, the Pakistan armed forces launched a comprehensive military campaign to root out the extremist insurgency in North Waziristan, the most troublesome of all the agencies in FATA. With the operation’s success, and the establishment of the government’s writ in these areas, the hope is that vaccinators will finally have access to these areas, thus allowing for blanket vaccinations in the country in well over two years. However, the mass exodus of the local population, which carries the polio virus, has also resulted in the escalated spread of polio, especially in KP.

“There are risks and opportunities of this endeavor,” says Dr Durry. “The risk is the spread of the virus, but the response is the vaccination itself. The opportunity is to get into these areas where there was no prior access to for blanket coverage.” Simultaneous, blanket vaccinations in every part of the country is the sole, surefire method of polio eradication in the country. The access problem may improve in the coming months, but the real issue will remain the “moribund” polio eradication program, as chastised by the IMB report. The government needs radically alter its attitude towards polio eradication in the country, and enforce a system that is transparent, efficient and provides blanket polio vaccination to children nationwide.

The author is a journalist and a development professional, and holds a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, NY, USA

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail.com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin

It is a matter of great national embarrassment that well over 90% of the cases reported worldwide in 2014 are reported from Pakistan.

All of this is not to say that Pakistan has made no progress in the two decades long fight against the disease. In 1994, the country recorded 25,000 cases. The 228 cases today are less than a percent of that. But contextually, Pakistan has lost significant traction, as the lowest number of cases (28), was reported in 2005, nine years ago. Despite incredible progress, and an expanded immunization program that operates with the help of a network of nearly 200,000 workers to help vaccinate 33.4 million children under the age of five in over 100 districts simultaneously, Pakistan seems to have taken several steps back. It is a massive undertaking, one that requires a colossal amount of coordination, transparency and ownership for it to work properly.

This coordination, transparency, and ownership of the government is severely lacking, according to the International Monitoring Board’s (IMB) chairman Dr Liam Dolandson. The IMB’s damning report called the polio eradication program a disaster which should not be allowed to continue even another month. The accompanying letter demanded “nothing short of transformative action”, and that the eradication program should be handed over to the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA). Saira Afzal Tarrar, Minister of State for National Health Services, Regulation and Coordination (NHSRC) has already stated that the NDMA is short-staffed and lacks the capacity to deal with this challenge. The NDMA spokesperson mirrors these sentiments, stating that the NDMA is willing to take on the challenge, but needs to be properly equipped to meet it.

The second big problem, often admitted by officials, and alluded to by experts, are the security-compromised areas in the country. In January 2014, Peshawar, capital of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province, was declared the largest polio reservoir in the world by the WHO. The latest seven polio cases, reported on October 28, 2014 came from KP and the adjoining Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). A Taliban-enforced ban has kept polio vaccination teams at bay in certain areas of FATA since June 2012.

[quote]They have been led to believe the campaign is a conspiracy[/quote]

Other problems include a small number of families who also refuse vaccinations, either out of fear of militant backlash, or because they have been led to believe the campaign is a conspiracy. Additionally, 60 polio workers have been killed since December 2012 in militant attacks, affecting vaccination campaigns in certain parts of the country.

On June 15, 2014, the Pakistan armed forces launched a comprehensive military campaign to root out the extremist insurgency in North Waziristan, the most troublesome of all the agencies in FATA. With the operation’s success, and the establishment of the government’s writ in these areas, the hope is that vaccinators will finally have access to these areas, thus allowing for blanket vaccinations in the country in well over two years. However, the mass exodus of the local population, which carries the polio virus, has also resulted in the escalated spread of polio, especially in KP.

“There are risks and opportunities of this endeavor,” says Dr Durry. “The risk is the spread of the virus, but the response is the vaccination itself. The opportunity is to get into these areas where there was no prior access to for blanket coverage.” Simultaneous, blanket vaccinations in every part of the country is the sole, surefire method of polio eradication in the country. The access problem may improve in the coming months, but the real issue will remain the “moribund” polio eradication program, as chastised by the IMB report. The government needs radically alter its attitude towards polio eradication in the country, and enforce a system that is transparent, efficient and provides blanket polio vaccination to children nationwide.

The author is a journalist and a development professional, and holds a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, NY, USA

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail.com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin