The MQM and PTI are facing a strategic identity crisis. The MQM has concluded that the politics of “national mutahidaism” has not yielded any significant dividends in Sindh or any other province, therefore it is time to beat the drums of “provincial muhajarism” to stave off political threats to its traditional “muhajir” vote bank in the urban areas of Sindh. The PTI has concluded that the democratic route to elections is long and uncertain, therefore it is time to explore shortcuts to power via conspiracies with disgruntled elements in the military and judiciary. Both strategies are full of contradiction and confusion.

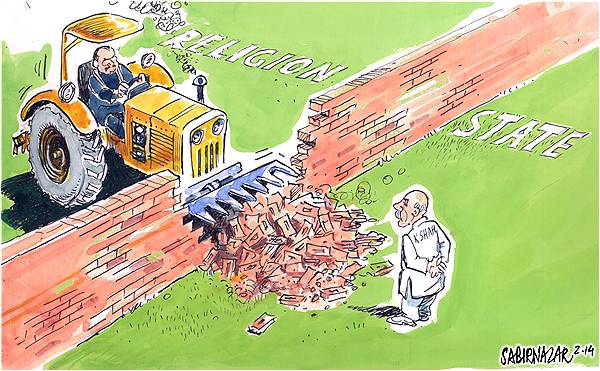

The MQM has quit the PPP government in Sindh for the umpteenth time. In the past, a parting of ways with the PPP was always part of the game of leveraging power and patronage. This time, however, the pretext is unprecedentedly “ideological”. The MQM has taken umbrage over a statement by the PPP Leader of the House in the Senate, Khurshid Shah, that it is an “insult” today to refer to the migrants from India into Pakistan at the time of partition as “mujahirs”. His argument is that the term “muhajir” connotes a temporary or transitional arrangement for foreigners whereas the “muhajirs” of 1947 have been fully and permanently integrated into the organs of the Pakistani state and society, to the extent that their Urdu language is the national language of the country.

Khurshid Shah has stated a fact. But it is tinged with the power politics of Sindhi ethnic nationalism and PPP provincialism. In the past such PPP provocations were par for the course for the MQM. But the MQM faces multiple threats within and without today that have required it to take such a shrill hardline position, going so far as to charge Mr Shah for “blasphemy” against “muhajirs” since the Prophet of Islam (pbuh) was also a “muhajir” from Mecca to Medina. Several factors are at stake here.

First, the MQM hasn’t been able to extract any significant mileage from changing its name from Muhajir Qaumi Movement (denoting a political-ethnic base) to Muttahida Qaumi Movement denoting a national platform. It has made no headway in the other provinces. Instead, the ANP and PTI are making inroads into its traditional vote bank in the urban areas of Sindh, especially Karachi, the former on the basis of Pasthtu-speaking “refugees” from KPK, FATA and even Afghanistan, and the latter on the basis of a demographic shift in population favouring the young between the ages of 18-29 who want “change” from the traditional pattern of political parties. Second, the MQM’s militant wing which used to call the shots in Karachi as a powerful tool for leveraging power, has suffered a setback following an effective Rangers-led federal operation to cleanse the city of criminal elements, many from the MQM. Third, the PPP is in the process of formulating a law for local body elections that will tilt power and patronage toward PPP appointed provincial administrators instead of local politicians, thereby depriving the MQM of its traditional right to administer Karachi on the basis of winning the local elections. Fourth, the MQM is facing some significant splits and desertions following pressure from the British government on Altaf Hussain in London regarding the murder of Imran Farooq and money laundering. Several stalwarts have left the party and are in hiding. Under the circumstances, it seems that its leadership has decided to hunker down and defend its core interests by raising the spectre of an erosion of Sindhi “muhajir” rights that always evokes a militant response from its traditional seats of support.

The PTI is facing a serious dilemma too. Its dharnas and jalsas have failed to overthrow Nawaz Sharif because the “third umpire” – disgruntled elements in the military who have been egging Imran Khan on —has not raised his finger. Tahirul Qadri has packed his bags and quit. A degree of fatigue has set in among his supporters. This is reflected in internal party dissent over the logic of resigning from the National Assembly while staying put in KPK as a device to hasten the end of the Nawaz regime. The Supreme Court, too, has refused to entertain PTI petitions to declare the 2013 elections as rigged. If Imran insists on continuing on his current path without success, his supporters will drift away and think twice before returning to his fold the next time. If he retreats like Qadri, he would erode his image of infallibility. In a last ditch effort he has summoned his supporters to Islamabad on November 30 to hurl a final threat to Nawaz Sharif. Whether the crowds become violent or disperse peacefully, the outcome is not likely to be favourable.

Both Altaf Hussain and Imran Khan need a reality check. Their current tactics and strategies are flying against the grain of popular mood. They should disavow shortcuts to power and dig in for the long democratic haul.

The MQM has quit the PPP government in Sindh for the umpteenth time. In the past, a parting of ways with the PPP was always part of the game of leveraging power and patronage. This time, however, the pretext is unprecedentedly “ideological”. The MQM has taken umbrage over a statement by the PPP Leader of the House in the Senate, Khurshid Shah, that it is an “insult” today to refer to the migrants from India into Pakistan at the time of partition as “mujahirs”. His argument is that the term “muhajir” connotes a temporary or transitional arrangement for foreigners whereas the “muhajirs” of 1947 have been fully and permanently integrated into the organs of the Pakistani state and society, to the extent that their Urdu language is the national language of the country.

Khurshid Shah has stated a fact. But it is tinged with the power politics of Sindhi ethnic nationalism and PPP provincialism. In the past such PPP provocations were par for the course for the MQM. But the MQM faces multiple threats within and without today that have required it to take such a shrill hardline position, going so far as to charge Mr Shah for “blasphemy” against “muhajirs” since the Prophet of Islam (pbuh) was also a “muhajir” from Mecca to Medina. Several factors are at stake here.

First, the MQM hasn’t been able to extract any significant mileage from changing its name from Muhajir Qaumi Movement (denoting a political-ethnic base) to Muttahida Qaumi Movement denoting a national platform. It has made no headway in the other provinces. Instead, the ANP and PTI are making inroads into its traditional vote bank in the urban areas of Sindh, especially Karachi, the former on the basis of Pasthtu-speaking “refugees” from KPK, FATA and even Afghanistan, and the latter on the basis of a demographic shift in population favouring the young between the ages of 18-29 who want “change” from the traditional pattern of political parties. Second, the MQM’s militant wing which used to call the shots in Karachi as a powerful tool for leveraging power, has suffered a setback following an effective Rangers-led federal operation to cleanse the city of criminal elements, many from the MQM. Third, the PPP is in the process of formulating a law for local body elections that will tilt power and patronage toward PPP appointed provincial administrators instead of local politicians, thereby depriving the MQM of its traditional right to administer Karachi on the basis of winning the local elections. Fourth, the MQM is facing some significant splits and desertions following pressure from the British government on Altaf Hussain in London regarding the murder of Imran Farooq and money laundering. Several stalwarts have left the party and are in hiding. Under the circumstances, it seems that its leadership has decided to hunker down and defend its core interests by raising the spectre of an erosion of Sindhi “muhajir” rights that always evokes a militant response from its traditional seats of support.

The PTI is facing a serious dilemma too. Its dharnas and jalsas have failed to overthrow Nawaz Sharif because the “third umpire” – disgruntled elements in the military who have been egging Imran Khan on —has not raised his finger. Tahirul Qadri has packed his bags and quit. A degree of fatigue has set in among his supporters. This is reflected in internal party dissent over the logic of resigning from the National Assembly while staying put in KPK as a device to hasten the end of the Nawaz regime. The Supreme Court, too, has refused to entertain PTI petitions to declare the 2013 elections as rigged. If Imran insists on continuing on his current path without success, his supporters will drift away and think twice before returning to his fold the next time. If he retreats like Qadri, he would erode his image of infallibility. In a last ditch effort he has summoned his supporters to Islamabad on November 30 to hurl a final threat to Nawaz Sharif. Whether the crowds become violent or disperse peacefully, the outcome is not likely to be favourable.

Both Altaf Hussain and Imran Khan need a reality check. Their current tactics and strategies are flying against the grain of popular mood. They should disavow shortcuts to power and dig in for the long democratic haul.