The Ghorid Minaret of Afghanistan, also known as the Minaret of Jam, stands as an emblem of medieval Islamic architecture and one of Afghanistan's most significant historical sites. Nestled in the remote valleys of the Hari River in Ghor Province, this towering structure, estimated to have been constructed in the late 12th century, offers not only a glimpse into the architectural grandeur of the Ghori dynasty, but also deep insight into the political, cultural, and religious milieu of the time. Its isolated location and monumental design have earned it recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage site, symbolising both the achievements and the turbulent history of the Ghorids, a dynasty that played a pivotal role in the spread of Islam and the establishment of Afghan identity during the medieval period.

The Ghori dynasty, to which the Minaret of Jam owes its origins, was an Islamic dynasty of Eastern Iranian descent. Rising to prominence in the region of Ghor, which is a rugged, mountainous area in what is now central Afghanistan, the Ghorids established their power in the wake of the Ghaznavid Empire's decline. They expanded their reach through military means and strategic alliances, eventually controlling territories stretching across modern-day Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, and northern India. Under the leadership of Muhammad Ghori and his brother Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad, the Ghorids fostered a cultural renaissance in the region. They patronised art, architecture, and literature.

The construction of monumental structures like the Minaret of Jam served to broadcast their newfound influence and the legitimacy of their rule.

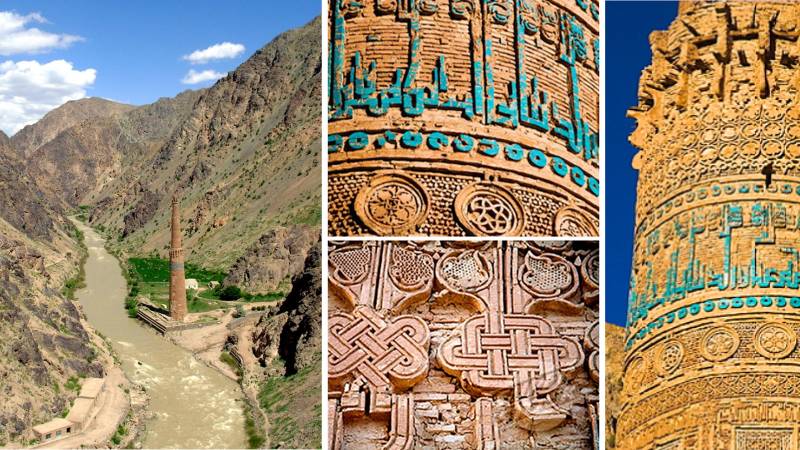

Standing over 62 meters tall, the Minaret of Jam is an architectural marvel. Built from fired bricks, it is an impressive example of Islamic architecture that incorporates intricate decoration and Quranic calligraphy on its surface. Its cylindrical structure, tapering slightly towards the top, is covered in an elaborate geometric and calligraphic design. The minaret is decorated with Kufic and Naskhi scripts, stylised as continuous bands, featuring verses from the Quran, most notably the Surah Maryam. The inscriptions highlight the Ghor dynasty’s dedication to Islam and their desire to present themselves as defenders of the faith, which was crucial for their rule's legitimacy in a predominantly Muslim region.

The minaret’s ornamentation is unique, blending Central Asian, Persian and overall Islamic artistic influences. The calligraphy and geometric patterns are a testament to the high level of craftsmanship that flourished under the Ghorid dynasty. The tower’s decoration also emphasises mathematical precision, a skill highly valued in Islamic architecture. The division of the tower into distinct sections through alternating bands of calligraphy and ornamentation creates a sense of verticality, drawing the viewer’s eye upwards and enhancing the tower’s visual impact against the surrounding landscape. This effect also serves to emphasise the spiritual purpose of the structure, with its soaring height symbolising a connection between the earthly realm and the divine.

The location of the Minaret of Jam is unusual. Unlike other Islamic minarets, which are typically situated adjacent to mosques, the Minaret of Jam stands alone in a remote valley, far from any major settlement. Scholars have debated the reasons behind this isolated location, with some suggesting that it may have served as a victory monument commemorating the Ghori conquests. Others posit that the minaret may have been part of the lost city of Firuzkuh, a prosperous Ghorid city mentioned in historical records but whose precise location remains unknown. If Firuzkuh indeed surrounded the minaret, it would indicate that the region was once a thriving cultural and economic centre.

The site’s location on the Hari River also suggests that it might have been a waypoint for trade and pilgrimage routes, enhancing the minaret's strategic and symbolic significance.

The Qutub Minar in Delhi reminds us of the Minaret of Jam, both in its cylindrical shape and its intricate decoration

Historical accounts from the 12th and 13th centuries, such as those by Persian historian Minhaj al-Siraj Juzjani, mention the existence of Firuzkuh as a prominent city, flourishing under the Ghorids until it was ravaged by the Mongol invasions in the early 13th century. The Minaret of Jam would have been one of the tallest structures in Firuzkuh, possibly functioning as a symbol of the city’s wealth and as a beacon of the Ghorid dynasty’s influence in the region. The Mongol invasions, however, brought widespread destruction to the area, erasing much of the Ghorids’ legacy and turning Firuzkuh into a memory, with the minaret remaining as one of the few surviving testaments to the city’s former glory. The minaret’s survival through centuries of conflict and natural disasters highlights its resilience, though it now faces serious threats from erosion, earthquakes, and neglect.

The Ghorids, unlike their predecessors, the Ghaznavids, did not focus primarily on establishing a centralised empire. Instead, they utilised a more feudal approach, granting autonomy to local rulers and tribes within their territories. This strategy allowed them to exert influence over a vast region while avoiding direct confrontation with powerful enemies. The Minaret of Jam stands as a reminder of this delicate balance, a symbol of the Ghori dynasty's successful unification of diverse cultural and ethnic groups under the banner of Islam and shared artistic and architectural heritage.

The spread of Islam under the Ghorid dynasty was accompanied by an emphasis on Islamic education and the establishment of religious institutions. The Ghorids encouraged the construction of madrasas, mosques, and other religious buildings to promote Islamic learning and scholarship. The Minaret of Jam, with its inscriptions from the Qur'an, reflects this dedication to Islamic knowledge and the propagation of faith. Furthermore, it may have served as a symbol of guidance and inspiration for travellers and pilgrims who passed through the region, reinforcing the Ghorid dynasty’s role as patrons of Islamic civilisation in Central Asia.

The architectural style of the Minaret of Jam had a lasting impact on Islamic architecture in South Asia. Following the Ghori conquest of parts of northern India, the dynasty’s architectural and artistic influences began to permeate the Subcontinent, ultimately laying the groundwork for the architectural styles of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire.

The Qutub Minar in Delhi, for example, reminds us of the Minaret of Jam, both in its cylindrical shape and its intricate decoration, and is often considered to be inspired by the Afghan structure. When we note the spread of Ghori architectural elements, it shows the cross-cultural exchanges that occurred as a result of the dynasty’s expansion, with the Minaret of Jam serving as a bridge between Central Asian and South Asian architectural traditions.

Despite its historical and cultural importance for the entire region of Central and South Asia, the Minaret of Jam is currently under threat. The site’s remote location has contributed to its preservation over the centuries, but it has also left it vulnerable to natural erosion, flooding and seismic activity. In recent decades, the minaret has been subjected to significant damage from flooding caused by the Hari River, which flows nearby, as well as from the instability of the surrounding terrain. Afghanistan’s prolonged periods of political instability have made it difficult to implement effective conservation measures, and the minaret remains at risk of further deterioration. UNESCO has listed the Minaret of Jam as a World Heritage site in danger, recognising the urgent need for preservation efforts to protect this unique monument.

Efforts to safeguard the Minaret of Jam have encountered numerous challenges, including limited funding, a lack of technical expertise and ongoing security concerns in the region. Conservationists face the difficult task of stabilising the structure without altering its original design or compromising its historical integrity. International organisations have provided support for conservation projects, but progress has been slow, and the future of the minaret remains uncertain. Despite these challenges, the Minaret of Jam continues to capture the world’s imagination, drawing attention to the cultural and historical richness of Afghanistan and the need to protect its heritage.