You own a flat in Karachi’s Gulshan-e-Iqbal which you rent out to a family under a Tenancy Agreement. You make sure all the paperwork is in order so that you don’t run into any legal trouble. Two years down the road, however, when you tell them to vacate it so you get your flat back, the family refuses to leave despite being given notice and your nightmare begins. The thought of hiring a lawyer and making trips to the courts fills you with gloom, but you reluctantly go ahead, expecting a long drawn out ordeal. Mercifully it doesn’t turn out to be one and in 300 days you get your flat back.

As it turns out, this was a quick case. But most people have a poor opinion of the judicial system and they fearfully assume their cases will drag on for years, even decades. These opinions are based on either personal experience or stories heard from others, which may or may not be accurate. To discover the truth, I decided to conduct an empirical study with the Legal Aid Society on delays in civil (not criminal) court cases in the district judiciary from November 2016 till March 2017. The results were presented in April 2017 at an event organized by the Sindh Judicial Academy in Karachi. The full report is available at co.lao.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Final-Paper-1.pdf.

The study

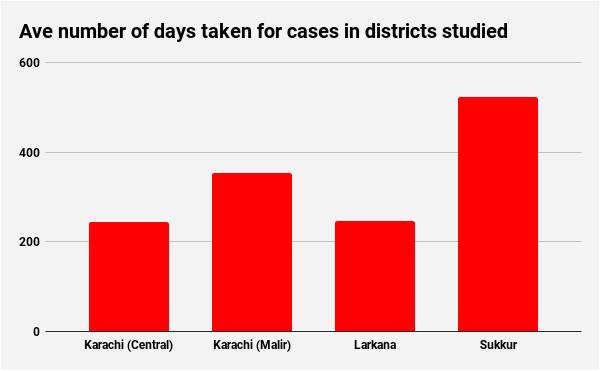

This study, titled Delays in Delivery of Justice in Civil Cases, began with the support of the Sindh Judiciary and their IT department. We chose two urban districts in Karachi (Central and Malir) and two peri-urban districts, Larkana and Sukkur. Since we wanted a current picture of the disposal of court cases, we chose October 2016 as our target month in the districts. The computerization of the records of cases helped considerably and we were given access to the Sindh Case Flow Management System-Software.

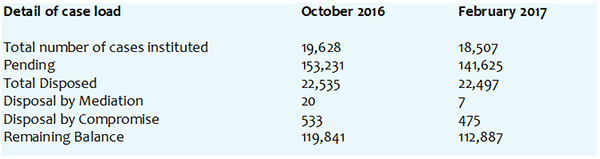

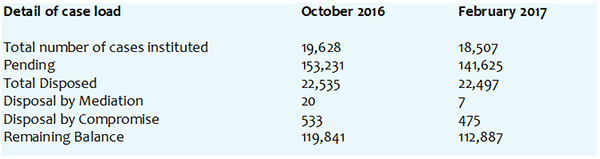

We studied a total of 429 cases manually along with the electronic reports provided by the IT department. The research team was made up of students of law from L’ecole for Advanced Studies in Karachi and lawyers of the Legal Aid Office in Sukkur and Larkana. Their work during December 2016 and January 2017 was instrumental in the study. We studied several types of cases ranging from ones on rent, appeals to executions. And we discovered that the rate at which cases are disposed of is better than we had imagined.

300-day average

We found that in Karachi Central and Malir, civil court cases can take an average of 300 days to wrap up. If the court decides that the tenant must leave the flat but the tenant disagrees, they can appeal the court’s decision; these kinds of appeals can take an average of 275 days to end. But the process doesn’t stop there. Even when the judge decides in your favour, the judgment must be ‘filed for execution’. This means that you must file or submit a separate request or application in court to have the court’s decision (for the tenant to leave) implemented. The court will appoint officials to be present to ensure that the tenant family is evicted and this process alone can take an average of 375 days. Therefore, if you file a civil case whose verdict is appealed (and then an execution is filed), you can expect to get your flat back in a little less than three years on average.

There is a law that applies to the way cases must take place and their deadlines. It is called the Civil Procedure Code, 1908 and it regulates a case from the time that it is filed until it ends. It gives specific timelines for each stage. For example: once you file your case against the tenants, they have 30 days to reply to your claims (or give a written statement). Unfortunately, the reality is that procedures are not necessarily followed. On average, it was noted that it can take almost six months for the written statement to be filed. If the tenant’s case is weak, their lawyer will try to drag the proceedings out to give their client more time by requesting adjournments and you will suffer. This time may also be used to attempt to reach a compromise between the litigating parties and it was noted that 27% of the cases studied ended in this manner.

Disposals

There are two other ways in which a case reaches its end in the legal system: it can be disposed after a full hearing with evidence being recorded etc. This is called disposal on merit and on average, 50% of the rent cases filed in the two districts were disposed of in this manner.

The second way for a case to end is disposal because your lawyer does not appear in court or follows the procedures within time. This is called disposal on default and an average of about 23% of cases fell in this category for this study.

Costs

You may find that the financial cost of litigation can be quite steep. This includes the cost of filing the case in court and the legal fees charged by the lawyer for his or her service. It has been observed in district courts that the lawyers who practice within its jurisdiction generally charge in installments and do not ask for a lump sum payment. This means you end up paying your lawyer small amounts and though this may appear to be easier on your pocket in the short run, in the longer run it can spiral. Also, if for some reason you fail to pay an installment, your lawyer may refuse to appear in court when the case is fixed, which can prove quite dangerous for you because the case can be ‘dismissed in non-prosecution’.

Backlog

You may read about or hear of cases which have been pending in court for decades. You may wonder how they are dealing with this backlog. Since 1999 the district judiciary has followed a Unit System policy. Each type of case is allocated a certain number of units—so the older the case, the more units are attached to its disposal and vice versa.

According to this system, each judge has to complete a total of 75 units each month and the District Judge has to complete 65 units each month. This policy has helped dispose of cases faster but there is no clear way evaluate quality. Therefore, the focus is more on numbers rather than the quality of the judgment. This needs to be studied if any reforms can be proposed. Also, so far the superior courts (high courts and the Supreme Court) are exempted from this policy, which makes one wonder whether perception of delays in the delivery of justice is based on cases before these higher forums.

You may also complain that there are too many strikes and court work is often suspended for reasons that have nothing to do with you or your case. This is frustrating for litigants. We tried to put together the total number of strikes each year to calculate exactly how many days of court work are lost. But we learnt that there is no central database where these instances are recorded. The most reliable information comes from the court files which record the suspension of work in order sheets for cases fixed on that day. Research showed that within the first three months of 2017, there were at least six strikes/suspension of work. The Sindh High Court Bar Association passed a resolution in January 2017 limiting strikes and suspension of work to specific circumstances. Death of a judge (retired or serving) or an advocate would result in the suspension of work after noon. Work will be suspended for the whole day only if a member of the legal community has been murdered, or there is a major national calamity. These policies can only be effective if they are followed.

Results

The study proved that disposal of cases is not as bad as one thinks and it is reassuring that your rent case in the district court can wrap up in about two years (if its verdict not appealed). However, since the superior courts are not part of the study, we have no statistics on their disposal numbers. For any meaningful reform to be introduced more research on the nuances of cases and time frames needs to be conducted across the hierarchy of courts so that the rate of the delivery of justice in civil cases can improve.

Summaiya Zaidi is a legal researcher and is pursuing her PhD in law

As it turns out, this was a quick case. But most people have a poor opinion of the judicial system and they fearfully assume their cases will drag on for years, even decades. These opinions are based on either personal experience or stories heard from others, which may or may not be accurate. To discover the truth, I decided to conduct an empirical study with the Legal Aid Society on delays in civil (not criminal) court cases in the district judiciary from November 2016 till March 2017. The results were presented in April 2017 at an event organized by the Sindh Judicial Academy in Karachi. The full report is available at co.lao.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Final-Paper-1.pdf.

The study

This study, titled Delays in Delivery of Justice in Civil Cases, began with the support of the Sindh Judiciary and their IT department. We chose two urban districts in Karachi (Central and Malir) and two peri-urban districts, Larkana and Sukkur. Since we wanted a current picture of the disposal of court cases, we chose October 2016 as our target month in the districts. The computerization of the records of cases helped considerably and we were given access to the Sindh Case Flow Management System-Software.

We studied a total of 429 cases manually along with the electronic reports provided by the IT department. The research team was made up of students of law from L’ecole for Advanced Studies in Karachi and lawyers of the Legal Aid Office in Sukkur and Larkana. Their work during December 2016 and January 2017 was instrumental in the study. We studied several types of cases ranging from ones on rent, appeals to executions. And we discovered that the rate at which cases are disposed of is better than we had imagined.

300-day average

We found that in Karachi Central and Malir, civil court cases can take an average of 300 days to wrap up. If the court decides that the tenant must leave the flat but the tenant disagrees, they can appeal the court’s decision; these kinds of appeals can take an average of 275 days to end. But the process doesn’t stop there. Even when the judge decides in your favour, the judgment must be ‘filed for execution’. This means that you must file or submit a separate request or application in court to have the court’s decision (for the tenant to leave) implemented. The court will appoint officials to be present to ensure that the tenant family is evicted and this process alone can take an average of 375 days. Therefore, if you file a civil case whose verdict is appealed (and then an execution is filed), you can expect to get your flat back in a little less than three years on average.

There is a law that applies to the way cases must take place and their deadlines. It is called the Civil Procedure Code, 1908 and it regulates a case from the time that it is filed until it ends. It gives specific timelines for each stage. For example: once you file your case against the tenants, they have 30 days to reply to your claims (or give a written statement). Unfortunately, the reality is that procedures are not necessarily followed. On average, it was noted that it can take almost six months for the written statement to be filed. If the tenant’s case is weak, their lawyer will try to drag the proceedings out to give their client more time by requesting adjournments and you will suffer. This time may also be used to attempt to reach a compromise between the litigating parties and it was noted that 27% of the cases studied ended in this manner.

Disposals

There are two other ways in which a case reaches its end in the legal system: it can be disposed after a full hearing with evidence being recorded etc. This is called disposal on merit and on average, 50% of the rent cases filed in the two districts were disposed of in this manner.

The second way for a case to end is disposal because your lawyer does not appear in court or follows the procedures within time. This is called disposal on default and an average of about 23% of cases fell in this category for this study.

The study proved that disposal of cases is not as bad as one thinks and it is reassuring that a rent case in the district court can wrap up in about two years (if its verdict not appealed). We studied a total of 429 cases from Karachi Central and Malir and Sukkur and Larkana in October 2016

Costs

You may find that the financial cost of litigation can be quite steep. This includes the cost of filing the case in court and the legal fees charged by the lawyer for his or her service. It has been observed in district courts that the lawyers who practice within its jurisdiction generally charge in installments and do not ask for a lump sum payment. This means you end up paying your lawyer small amounts and though this may appear to be easier on your pocket in the short run, in the longer run it can spiral. Also, if for some reason you fail to pay an installment, your lawyer may refuse to appear in court when the case is fixed, which can prove quite dangerous for you because the case can be ‘dismissed in non-prosecution’.

Backlog

You may read about or hear of cases which have been pending in court for decades. You may wonder how they are dealing with this backlog. Since 1999 the district judiciary has followed a Unit System policy. Each type of case is allocated a certain number of units—so the older the case, the more units are attached to its disposal and vice versa.

According to this system, each judge has to complete a total of 75 units each month and the District Judge has to complete 65 units each month. This policy has helped dispose of cases faster but there is no clear way evaluate quality. Therefore, the focus is more on numbers rather than the quality of the judgment. This needs to be studied if any reforms can be proposed. Also, so far the superior courts (high courts and the Supreme Court) are exempted from this policy, which makes one wonder whether perception of delays in the delivery of justice is based on cases before these higher forums.

You may also complain that there are too many strikes and court work is often suspended for reasons that have nothing to do with you or your case. This is frustrating for litigants. We tried to put together the total number of strikes each year to calculate exactly how many days of court work are lost. But we learnt that there is no central database where these instances are recorded. The most reliable information comes from the court files which record the suspension of work in order sheets for cases fixed on that day. Research showed that within the first three months of 2017, there were at least six strikes/suspension of work. The Sindh High Court Bar Association passed a resolution in January 2017 limiting strikes and suspension of work to specific circumstances. Death of a judge (retired or serving) or an advocate would result in the suspension of work after noon. Work will be suspended for the whole day only if a member of the legal community has been murdered, or there is a major national calamity. These policies can only be effective if they are followed.

Results

The study proved that disposal of cases is not as bad as one thinks and it is reassuring that your rent case in the district court can wrap up in about two years (if its verdict not appealed). However, since the superior courts are not part of the study, we have no statistics on their disposal numbers. For any meaningful reform to be introduced more research on the nuances of cases and time frames needs to be conducted across the hierarchy of courts so that the rate of the delivery of justice in civil cases can improve.

Summaiya Zaidi is a legal researcher and is pursuing her PhD in law