In his address at the Afghan parliament on December 25, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi struck a great note of optimism on regional anti-terror cooperation. “We know that Afghanistan’s success will require the cooperation and support of each of its neighbors. And all of us in the region — India, Pakistan, Iran and others — must unite, in trust and cooperation, behind this common purpose and in recognition of our common destiny.”

The applause was even louder when Modi said: “I hope that Pakistan will become a bridge between South Asia and Afghanistan, and beyond.”

Only three days earlier, Karen Pierce, the British ambassador to Afghanistan, resonated international concerns at an event of a Pakistan-Afghan Track 1.5 exercise titled ‘Beyond Boundaries’. The “threat to Pakistan (from terrorism and militancy) is not as existential as it is to Afghanistan… the past decade or so proves that a military solution is no option.” Ms Pierce cautioned that “what is going on in Afghanistan is threatening to Afghans as well as the extended communities, and hence the need for a coordinated honest attempt to take the road to reconciliation through negotiations.”

Two days after that, in a meeting with Pakistani and Afghan delegates of Beyond Boundaries that lasted for more than two hours, the soft-spoken Afghan national security advisor Haneef Atmar reflected on the same challenges. “We commit that Afghanistan will never allow the use of its territory by anyone for terrorist activities,” he said. “We expect the same from Pakistan and are ready to use mutual friends like China and the US. Is Pakistan ready to do that?”

While appreciating the Operation Zarb-e-Azb, he said he hoped it would also target those “networks of terror which continue to kill our innocent women and children.” He praised Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s “recognition of the National Unity Government to be the only legitimate government in Afghanistan”, which he said Afghan political circles regarded as a confidence building step.

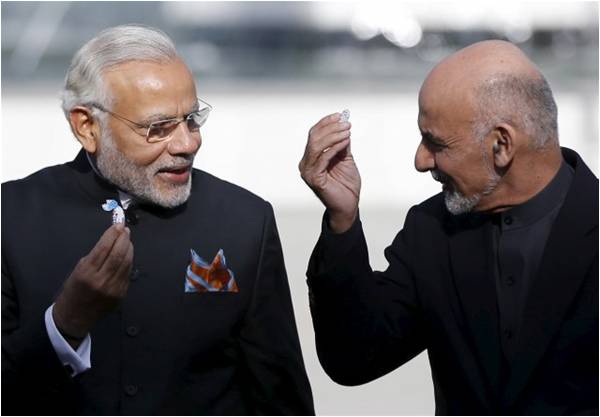

Then, on the heels of Modi’s visit to Kabul, Pakistan Army chief Gen Raheel Sharif met with Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and CEO Dr Abdullah Abdullah on December 27. They agreed to pursue peace and reconciliation with Taliban groups willing to join the process, and reiterated their resolve not to let anyone use their soil against each other. They also agreed to deal sternly with the elements crossing over and getting involved in violence on either side, through active intelligence sharing and intelligence-based operations.

They decided to establish a hotline between the directors-general of military operations and increase the frequency of military-to-military visits for better coordination.

In retrospect, these positive vibes from Afghan and foreign dignitaries marked a remarkable week of interactions – all converging on the need to reinitiate the reconciliation process as soon as possible. If the intentions are right, then Prime Minister Modi’s Lahore stopover is a huge step towards untying the complex gridlock involving India, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

A big consolatory feature of the week was that some of the policy convergences during Gen Sharif-President Ghani meetings resonated parts of a resolution that Pakistani and Afghan security experts had prepared a few days ago, urging both governments to join hands in the anti-terror war and pursue the path of reconciliation with the “reconcilable militants.”

“Elements who would still continue to pursue violence will be dealt with under a mutually worked out framework,” said an official statement. It said senior officials from Pakistan, Afghanistan, China and the United States will meet in January to devise a road map for the resumption of the stalled Afghan peace talks, with a clear demarcation of responsibilities of each stakeholder at all stages.

As a whole, the year-end activity revolving around Afghanistan sets the stage for a promising discourse in 2016. But that may not be easy. The path will be thorny and all sides will have to meet some challenges.

The first challenge for Pakistan is to neutralize the overriding misconception in Afghanistan, that Pakistan “benefits from a destabilized Afghanistan”. Former president Hamid Karzai is among the proponents of this narrative, although he admitted during a meeting with the Pakistani and Afghan security delegations that he does not read Pakistani newspapers any more.

The second challenge is to convince the Afghans that the Operation Zarb-e-Azb and Pakistan’s National Action Plan against terrorism mark a clear break from the past mistakes – the government’s writ has been extended to Waziristan, many pro-Al Qaeda clerics have been barred from appearing on TV, the TTP has been displaced, and the Supreme Court is fully supportive of the state’s efforts to enforce the rule of law. It would be easier to convince the Afghans of this if they saw that the groups they see as irreconcilable enemies are also being hunted down.

What most Afghan friends fail to recognize is that after a very long time, the US, the UK, Germany and China are empathetic towards Pakistan. This empathy has indeed instilled a new level of confidence in Pakistan, encouraging it to discard the cold-war era mindset and look at the security matrix through a new prism. Premier Modi’s statements in Kabul boost that optimism.

A combined challenge for New Delhi, Islamabad and Kabul is to gradually realign their interests in Afghanistan to minimize violence and to create space for the resumption of peace talks with the “reconcilable Taliban.” Trilateral suspicions currently trump all other aspects of bilateral or multi-lateral engagements.

While the American, Chinese and British trust in Pakistan is unparalleled as of now, Afghanistan and India need to take a fresh look at the gradual change in Pakistan, whose campaign against religious extremism and terrorism is constrained by a number of socio-political, ethnic and tribal considerations.

As 2016 begins, leaders in the three countries should bury the hatchet, give up proxy wars, and give way to confidence instead of suspicion. They must share responsibilities and together to defeat the enemies of peace and progress.

The writer heads the independent Centre for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad

Email: Imtiaz@crss.pk

The applause was even louder when Modi said: “I hope that Pakistan will become a bridge between South Asia and Afghanistan, and beyond.”

Only three days earlier, Karen Pierce, the British ambassador to Afghanistan, resonated international concerns at an event of a Pakistan-Afghan Track 1.5 exercise titled ‘Beyond Boundaries’. The “threat to Pakistan (from terrorism and militancy) is not as existential as it is to Afghanistan… the past decade or so proves that a military solution is no option.” Ms Pierce cautioned that “what is going on in Afghanistan is threatening to Afghans as well as the extended communities, and hence the need for a coordinated honest attempt to take the road to reconciliation through negotiations.”

Two days after that, in a meeting with Pakistani and Afghan delegates of Beyond Boundaries that lasted for more than two hours, the soft-spoken Afghan national security advisor Haneef Atmar reflected on the same challenges. “We commit that Afghanistan will never allow the use of its territory by anyone for terrorist activities,” he said. “We expect the same from Pakistan and are ready to use mutual friends like China and the US. Is Pakistan ready to do that?”

While appreciating the Operation Zarb-e-Azb, he said he hoped it would also target those “networks of terror which continue to kill our innocent women and children.” He praised Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s “recognition of the National Unity Government to be the only legitimate government in Afghanistan”, which he said Afghan political circles regarded as a confidence building step.

After a very long time, the US, the UK, Germany and China are empathetic towards Pakistan

Then, on the heels of Modi’s visit to Kabul, Pakistan Army chief Gen Raheel Sharif met with Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and CEO Dr Abdullah Abdullah on December 27. They agreed to pursue peace and reconciliation with Taliban groups willing to join the process, and reiterated their resolve not to let anyone use their soil against each other. They also agreed to deal sternly with the elements crossing over and getting involved in violence on either side, through active intelligence sharing and intelligence-based operations.

They decided to establish a hotline between the directors-general of military operations and increase the frequency of military-to-military visits for better coordination.

In retrospect, these positive vibes from Afghan and foreign dignitaries marked a remarkable week of interactions – all converging on the need to reinitiate the reconciliation process as soon as possible. If the intentions are right, then Prime Minister Modi’s Lahore stopover is a huge step towards untying the complex gridlock involving India, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

A big consolatory feature of the week was that some of the policy convergences during Gen Sharif-President Ghani meetings resonated parts of a resolution that Pakistani and Afghan security experts had prepared a few days ago, urging both governments to join hands in the anti-terror war and pursue the path of reconciliation with the “reconcilable militants.”

“Elements who would still continue to pursue violence will be dealt with under a mutually worked out framework,” said an official statement. It said senior officials from Pakistan, Afghanistan, China and the United States will meet in January to devise a road map for the resumption of the stalled Afghan peace talks, with a clear demarcation of responsibilities of each stakeholder at all stages.

As a whole, the year-end activity revolving around Afghanistan sets the stage for a promising discourse in 2016. But that may not be easy. The path will be thorny and all sides will have to meet some challenges.

The first challenge for Pakistan is to neutralize the overriding misconception in Afghanistan, that Pakistan “benefits from a destabilized Afghanistan”. Former president Hamid Karzai is among the proponents of this narrative, although he admitted during a meeting with the Pakistani and Afghan security delegations that he does not read Pakistani newspapers any more.

The second challenge is to convince the Afghans that the Operation Zarb-e-Azb and Pakistan’s National Action Plan against terrorism mark a clear break from the past mistakes – the government’s writ has been extended to Waziristan, many pro-Al Qaeda clerics have been barred from appearing on TV, the TTP has been displaced, and the Supreme Court is fully supportive of the state’s efforts to enforce the rule of law. It would be easier to convince the Afghans of this if they saw that the groups they see as irreconcilable enemies are also being hunted down.

What most Afghan friends fail to recognize is that after a very long time, the US, the UK, Germany and China are empathetic towards Pakistan. This empathy has indeed instilled a new level of confidence in Pakistan, encouraging it to discard the cold-war era mindset and look at the security matrix through a new prism. Premier Modi’s statements in Kabul boost that optimism.

A combined challenge for New Delhi, Islamabad and Kabul is to gradually realign their interests in Afghanistan to minimize violence and to create space for the resumption of peace talks with the “reconcilable Taliban.” Trilateral suspicions currently trump all other aspects of bilateral or multi-lateral engagements.

While the American, Chinese and British trust in Pakistan is unparalleled as of now, Afghanistan and India need to take a fresh look at the gradual change in Pakistan, whose campaign against religious extremism and terrorism is constrained by a number of socio-political, ethnic and tribal considerations.

As 2016 begins, leaders in the three countries should bury the hatchet, give up proxy wars, and give way to confidence instead of suspicion. They must share responsibilities and together to defeat the enemies of peace and progress.

The writer heads the independent Centre for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad

Email: Imtiaz@crss.pk