NOTE: This is the first part of a two-part article which fully explores and analyses the correlation between the insanity defence and the imposition of the death penalty. You can read the second part here.

In the symphony of Pakistan's legal realm, an often-muted melody resounds—a melody woven from the stories of minds caught in the vortex of mental illness. With a canvas as intricate as the human psyche, the intersection of law and mental health beckons us to explore the alleys of compassion, justice, and the relentless pursuit of equilibrium. As we unlock this evocative narrative, we find ourselves treading the path of empathy, seeking to unshroud the enigma of mental illness law in the heartbeat of Pakistan's legal consciousness.

A short while back, the repercussions of a groundbreaking decision shook the legal landscape of Pakistan. In an instance that drew both scrutiny and debate, the Supreme Court of Pakistan issued a landmark verdict that sent ripples through the understanding of mental health. In a turn that startled many, the court declared schizophrenia as a condition that did not merit the classification of a "mental illness."

The unfolding of this pivotal verdict echoes the case of Imdad Ali, which came before the same Supreme Court in April 2016. This case highlighted the complexities of the intersection between mental health and legal determinations. It underscored the challenge of comprehending the intricacies of psychological conditions within the context of justice.

In this milieu, the legal world faced an enigma — how to reconcile mental health's subjective contours with the law's objective framework. As the echoes of this decision continue to ripple across legal corridors, they compel us to reflect on the evolving nature of justice, the challenges of understanding mental health nuances within legal paradigms, and the critical need for a balanced approach when deciphering the intricate tapestry of the human mind within the realm of the law.

The court's determination rested on a meticulous examination, drawing from a dictionary delineation of schizophrenia and a precedent set by the Supreme Court of India in 1976 during the Amrit Bhushan case. This landmark ruling posited that schizophrenia does not universally entail a perpetual disorder and might not qualify as a legitimate defence in cases involving charges such as murder.

In Pakistan, the assimilation of the McNaughton Rules into its penal code serves as the foundational cornerstone for the jurisprudential handling of insanity within criminal law

The verdict rendered in Imdad Ali's case ignited a poignant dialogue within the legal and intellectual circles, both within Pakistan and reverberating far beyond its borders. This discourse assumed a deeply contemplative tone, weaving around the core inquiries that arose:

- Can the requirements stipulated by Article 10-A of the Constitution be considered as duly met if individuals beset by mental disabilities find themselves bereft of safeguards throughout the investigation and trial phases?

- To what extent do Pakistan's procedural protocols in criminal matters harmonise with the precepts enshrined within the 2011 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)? This international covenant mandates that endorsing nations allocate the necessary resources for individuals with disabilities to exercise their legal privileges effectively and be shielded from discriminatory practices.

- While acknowledging that utilising the insanity defence may elude those contending with schizophrenia, does this exception implicitly negate their intrinsic entitlement to medical intervention? The aftermath of this deliberation is tinged with a sombre reflection on the poignant interplay of justice, mental health, and human rights — a nexus wherein vulnerable individuals navigate intricate pathways within the legal framework. At the same time, society grapples with the bounden duty to uphold their well-being and rights.

This article meticulously explores the intricate correlation between the insanity defence and the imposition of the death penalty, contextualised explicitly within the Imdad Ali case. Central to this analysis are two widely acknowledged dimensions within the realm of insanity defence: its applicability during the criminal act and its relevance throughout the stages of interrogation, trial, and subsequent punishment. A central contention is presented, asserting the conspicuous absence of the latter facet of the insanity defence within Pakistan's legal structure.

Moreover, the article ventures into the dichotomy of enduring versus transient insanity, a conceptual framework introduced through the Supreme Court's verdict in the Imdad Ali case. This juxtaposition is subjected to a thorough evaluation, placed against the backdrop of established jurisprudence concerning the insanity defence. This evaluation is skillfully interwoven with pertinent global advancements in human rights.

The discourse then shifts to illuminate the inadequacies that permeate Pakistan's existing legislation concerning insanity. These deficiencies encompass the deficiency of competency assessments, the absence of an all-encompassing definition of insanity, and the conspicuous lack of provisions to ensure proficient legal representation.

As this analysis culminates, it's imperative to underscore the possible repercussions of this legal landscape. The intricate interplay between these nuanced concepts puts those accused under such circumstances in a precarious position. This precariousness teeters on the edge of an often elusive and ambiguous precipice. The fragile boundary separating sanity from culpability becomes a battlefield of susceptibility — a trial marked by opacity and enigma. A prevailing sense of vulnerability takes root in this intricate legal realm, evoking a poignant sentiment of helplessness for those entrapped within its convoluted confines.

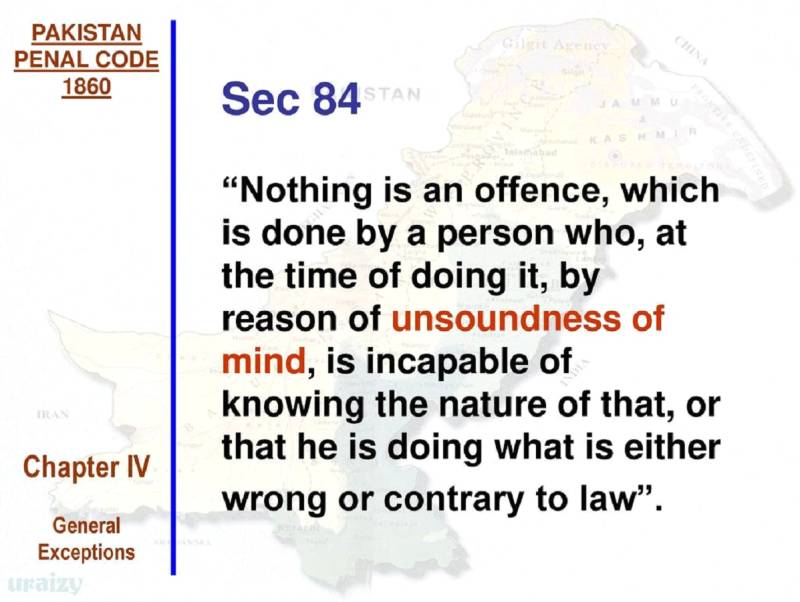

It is paramount to delve into the historical underpinnings that have shaped the very bedrock of Insanity laws. In Pakistan, the assimilation of the McNaughton Rules into its penal code serves as the foundational cornerstone for the jurisprudential handling of insanity within criminal law. This is impeccably demonstrated through the articulation found within Section 84 of the Pakistan Criminal Code of 1898. This section establishes a comprehensive and exhaustive framework, dealing intricately with matters about insanity within the intricate tapestry of the criminal justice system.

Section 84 is a singularly comprehensive provision that governs the legal treatment of insanity. Operating under the purview of this section, the guiding principle is that an individual cannot be held accountable if their mental faculties have been compromised to an extent where the capacity to distinguish right from wrong becomes grievously impaired. What is particularly noteworthy is the deliberate semantic choice within the legislative domain. The term "unsoundness of mind" is employed within Section 84 instead of the more traditional "insanity." This deliberate phrasing strategy is a calculated manoeuvre intended to broaden and meticulously delineate the scope of this legal concept. It encompasses a spectrum that spans persistent and transient incapacitation, a nuanced dimension vividly encapsulated in the legal precedent set forth by the case of Mehrban Alias Munna v. The State (2002). Crl. Appeal No. 65 of 2019 - Islamabad High Court.

From the outset, it is imperative to emphasise that most common law jurisdictions recognise the defense of insanity. This legal principle stipulates that if the accused cannot comprehend the ramifications of their actions when committing the offense, they cannot be subject to penalisation or execution. This defense is enshrined within Section 84 of the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC). Implementing the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) of 1966 and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) of 2011 introduced a further facet to this defense. This dimension necessitates the consideration of the mental well-being of the accused throughout their engagement with the criminal justice system, extending the relevance of insanity not solely to the moment of the crime but also encompassing stages such as interrogation, trial, and punishment.

Presently, it is judicious to affirm that global perspectives diverge on the latter dimension of this defense, specifically its applicability during the phases of interrogation, trial, and execution. Certain judicial instances have endorsed the contention that impairment of cognitive faculties constitutes a valid justification for postponing the execution of death sentences. Conversely, other jurisdictions have maintained that insanity does not warrant a deferment of execution. Legal systems aligned with the former viewpoint advocate that if the defendant is mentally incapacitated, a respite from capital punishment is justified to allow them to recuperate from their ailment. Within this perspective, extinguishing the life of an individual with a mental disorder is deemed to infringe upon the rights of individuals with disabilities. Additionally, it has been postulated that the execution of an individual who lacks comprehension of the rationale behind their punishment would fail to achieve the intended objectives of retribution or deterrence.

On the contrary, legal systems that do not endorse the defense of insanity during the stages of interrogation, trial, and execution assert that the plea of insanity should solely pertain to the moment of the offense and not extend after that. Within this paradigm, it is posited that if the accused could discern right from wrong precisely during the commission of the crime, there is no warrant for suspending the sentence.

In summary, the complexities of the insanity defense reflect divergent viewpoints across global legal landscapes. The evolving nature of legal interpretations underscores the intricate balance between considerations of mental health, justice, and the rights of persons with disabilities. The question of whether insanity should factor into the entirety of the criminal justice process continues to elicit robust debate within international legal discourse.

Given Pakistan's legal framework, specifically Section 84 of the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC), protection is afforded only to those with mental disabilities at the time of the crime. Consequently, Imdad Ali received no consideration for his schizophrenia during trial and sentencing

To grasp the contrasting viewpoints outlined above, it is essential to delve into the rationale behind deferring punishment for individuals with mental disabilities. Legal systems advocating for postponement assert that insanity renders a defendant susceptible to coerced confessions, undue compliance, and susceptibility during the interrogation phase, thereby undermining the fundamental tenets of a just trial. Moreover, it is contended that mental illness hampers effective communication between a suspect and their legal counsel, leaving the individual defenseless during trial and appellate proceedings. The incapacity stemming from mental illness obstructs the comprehension of the connection between criminal actions and subsequent penalties. In this context, executing an offender in a state of delirium fails to achieve the primary goals of punishment, namely deterrence and retribution.

In light of these considerations, it becomes evident that the insanity defense carries relevance not solely at the time of the crime's commission but throughout the entirety of the suspect's engagement with the criminal justice system. The initial ruling of the Supreme Court in the Imdad Ali case adopted a stance that regarded insanity as a defense exclusively applicable if the accused was mentally impaired during the crime's occurrence and not beyond.

Advancements in international law, which Pakistan has embraced through accedence, coupled with the underlying principles supporting theories of punishment as deterrence, necessitate reevaluating this approach. It is imperative to ensure that the criteria for providing a fair trial to individuals grappling with disabilities are fully met.

As previously elucidated, the Supreme Court's verdict in the Imdad Ali case stipulated that schizophrenia, a temporary mental disorder, should not be equated with a permanent impairment of mental faculties warranting clemency during execution. The court anchored its decision on a four-decade-old Indian legal precedent and a fifty-year-old dictionary definition of schizophrenia provided by the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

It is pivotal to highlight two pertinent points. Firstly, the Indian Supreme Court, whose verdict was invoked to support this stance, subsequently altered its perspective. The 2014 Shutrugan Chauhan case saw the Indian Supreme Court suspending the execution of a schizophrenic individual, reasoning that capital punishment primarily serves retribution and withholding execution until the prisoner comprehends the rationale is ethically imperative.

Secondly, given the rapid advancement in modern medical science, reliance on a fifty-year-old dictionary definition to ascertain the permanence or temporariness of an illness is precarious.

The approach endorsed by Pakistan's Supreme Court may yield two significant repercussions. A suspect might inadvertently relinquish their right to appeal, especially if their legal representative is not vigilant and the suspect grapples with periods of delirium. Moreover, a suspect in such a state might struggle to effectively communicate with their lawyer during post-trial and post-conviction proceedings. It is evident that both these scenarios bear implications for the right to a fair trial as enshrined in Article 10-A of Pakistan's Constitution.

In the Imdad Ali case, a government-appointed medical team concluded that he had schizophrenia 12 years after the murder. However, the lack of medical records before that assessment made it uncertain whether he had the condition during the commission of the crime.

Given Pakistan's legal framework, specifically Section 84 of the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC), protection is afforded only to those with mental disabilities at the time of the crime. Consequently, Imdad Ali received no consideration for his schizophrenia during trial and sentencing. While constrained by the existing insanity law, the pivotal issue was the request to postpone execution for treatment.

Section 464 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CRPC) provided some guidance, allowing a magistrate to assess mental health and potentially postpone proceedings through a medical board. However, such efforts could be futile if the accused is returned to inadequate prison conditions, where temporary ailments might evolve into permanent ones. In Imdad Ali's case, the Supreme Court deemed schizophrenia non-permanent, not under the Mental Health Ordinance's definition of a 'mental disorder,' permitting treatment before execution. Although execution was later stayed, the rationale was unprovided. This analysis focuses on the initial refusal of postponement, shedding light on the limitations within the legal framework governing the trial of mentally impaired suspects.

The legal landscape concerning the insanity defense has evolved significantly since 1968, when Karl Menninger of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) questioned the existence of schizophrenia. Contemporary jurisprudence has progressed to incorporate international legal standards from the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) of 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) of 2011. These conventions emphasise protection from cruel and degrading treatment, elimination of discrimination, and provision of necessary resources for individuals with disabilities to ensure the fair exercise of legal rights.

In 2006, the American Bar Association (ABA) endorsed a resolution stipulating that mentally ill defendants should be spared from execution if certain conditions are met:

⦁ Unclear intent during the commission of the crime.

⦁ Inability to effectively consult with their lawyer during various stages of legal proceedings.

⦁ Mental condition at the time of execution.

⦁ Capacity to waive appeals due to mental state.

These criteria underscore that temporarily insane suspects are just as vulnerable in presenting their defense as those with enduring mental disorders. Additionally, executing such individuals would be as futile as permanently deranged suspects if they fail to comprehend the link between their crime and punishment. Consequently, legal frameworks should be formulated to allow courts to place such suspects in mental health institutions for rehabilitation.

NOTE: This is the first part of a two-part series of articles which fully explore and analyse the correlation between the insanity defence and the imposition of the death penalty. For the second party, please click here.