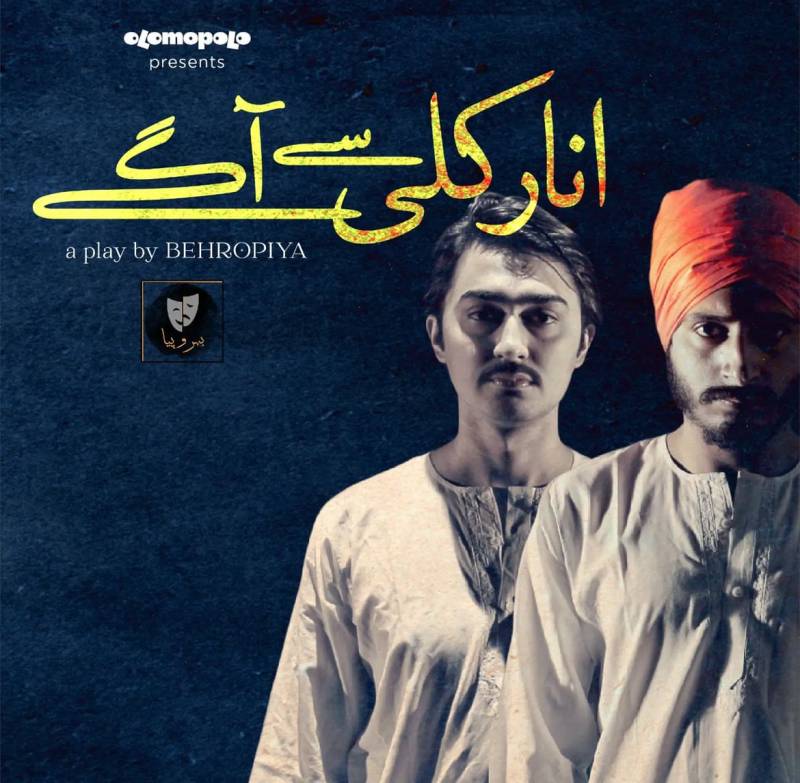

In the last week of October, I had the wonderful experience of attending Olomopolo’s staging of Behrupiya Production’s play– Anarkali Se Aagey. Director Fawad Khan, writer Abdul Rehman and the titular characters played by Abdul Rehman himself, alongside Rayyan Khan, put to stage a story of freedom, revolution and blood that mars the history marked by the search for both.

In light of conversations pertaining to the act of revolution stirring the media, print and otherwise, this was quite the experience. You see it every day, in statements polluting social media timelines with intricately typed, edited, and typed text. “I condemn all forms of violence,” because that is what is socially acceptable, is it not?

But when you say you condemn violence from the oppressor, why do you also condemn the years of anger and spite that brews in the hearts of the oppressed and results in violence as a direct result? Non-violence is the preferred act of resistance, holding placards in the face of gunfire and hurled slurs; and repeatedly I am reminded of Mao Zedong’s words: “Revolution is not a dinner party, nor an essay, nor a painting…revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another."

For my preliminary research, I did end up reading the summary of the play– an evening of December 27th, 1928, a white police officer is murdered. It is suspected that the act is carried out by HSRA, a revolutionary group, and police, searching for them, pore over the streets of Lahore and especially its universities. The story is set in the room of one of these universities.

I decided to read up on the HSRA before I saw the play, so I could fully grasp the full spectrum of what I was to experience. Of course, like any other leftist, I had heard of the man termed Shaheed-e-Azam of the pre-partition revolutionaries, Bhagat Singh, but I knew very little of HSRA as an organisation.

Leftism arose as a movement especially amongst Punjabi revolutionaries that saw their homeland crumble in face of the British empire’s massacre of India– they stole, ravaged, killed, looted, and no one seemed to answer their violence with violence. Who was to take up arms against the oppressor, had 1857’s War of Independence not been enough an example for anyone that even imagined doing so? Ghadar, a leftist newspaper published in 1913 published a regular record sheet of the British and their exploits in the motherland– stealing at least “fifty crore rupees annually… inflicting families, and sowing communal divide.” (Raza, Ali, “Revolutionary Pasts”).

Who was to take up arms against the oppressor, had 1857’s War of Independence not been enough an example for anyone that even imagined doing so? Ghadar, a leftist newspaper published in 1913 published a regular record sheet of the British and their exploits in the motherland– stealing at least “fifty crore rupees annually… inflicting families, and sowing communal divide.”

Even away from home, the population of the subcontinent were treated as subjects, enslaved at the hands of British imperialism, and according to Sohan Singh Bakhna, “...a slave can never attain dignity or respect in the world.” It is not surprising then, that the urban centres of Punjab, the pinnacles of higher education and oft frequented by embittered young men who just wanted change, grew to be the centres of such revolutionary groups – one of them, the HSRA or the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association or Army; that Bhagat Singh was a part of. This party roused the sentiments of young men tired of the “talks” and “protests,” all evoking nothing in the heart of the imperialists other than more violence and ridicule.

The story of Anarkali se Agey is set in the era of this divide, this rage and this anger. The storyline has such intricate attention to detail that you can not help but become deeply embedded in, as the viewer. It opened with a clipped voice over stating that it is a dark night on the 27th of December, 1928, and the setting is a hostel room in Government College Lahore, inhabited by two students– Baldev Singh, a Sikh and Riaz Ali, a Muslim. It opens with Riaz scrambling to hide something in his closet, just as Baldev steps in. A friend with me nudged me as the scene played out and commented on how the two seem to be the exact polar opposites, just as we were– Baldev, the loud, boisterous and opinionated English Literature student and Riaz, the toned-down, calm and logical History student. What I enjoyed about the play is merely the fact that it is a conversation between friends, one that transcends timelines and history to stand pertinent to today’s time and history. The two argue – Riaz firmly believes in non-violence as an act of revolution and has quit Congress to join Muslim League; he believes through peaceful protests, electoral procedures and talks, the British will leave the subcontinent and the masses will settle into their own states on the basis of majority and minority in religion. Baldev argues– “It is better to indulge in anarchy than to be a slave to the British.” Baldev argues for the minorities and their displacement in light of independence– as if they are objects that will be left to the mercy of borders.

Baldev argues against the education system the British have set up, and scoffs at Riaz’s appreciation of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan. “He actively worked for the education of Muslims, and their enlightenment, look at what feats MAO College has achieved!” Riaz yells, and he scoffs, answering in his quintessential Punjabi accent, so excellently done. “Sir. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan has introduced to the Muslims the British system of education, how inspirational.” To the soothing balm of Riaz’s words, Baldev’s words cut the tension filled air in a striking manner.

The open-ended conclusion also leaves a question for the audience– what is revolution? Is it a theatrical display, or is it something that must be radical? Is murdering for revolution really worth it, when one tyrant can skilfully be replaced by another, and is dismantling the system much more complex? You’re allowed to reach your own conclusions as a viewer.

They pace around the room, they eat together, and share a cigarette. It is in one of these scenes where they talk over a cigarette and stare into the distance that the viewer feels the 4th wall is broken, and they’re staring right into their souls. “This is not a system, Riaz, this is a swamp. All this mess is going to pollute the lands, even if the British leave.” All these conversations are happening in the backdrop of a white English officer, John P. Saunders, that has been shot– and all suspicion is falling on young men in universities. Riaz argues that Saunders was a white imperialist, yes, but he was a human, and no human deserves to die. Baldev snaps– the white imperialist does not consider the burdened Indian a human, then why must they?

The end of the play is marked by an accumulation of events that raise the level of anxiety you feel as a viewer skyrockets through the roof. Like the night, marred by secrecy and intrigue, the stage mirrors it too. Accusations of involvement in the murder come to light, as Riaz produces from his cupboard the pistol Baldev had hidden in his, and confronts him. “Are you not a part of the HSRA? Were you not there when that officer was murdered? And what about the Head Constable? You’re murdering your own people in the name of freedom?” That is when Baldev names the conspirators in the murder– revolutionaries, Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, Azad– they had wanted to avenge the murder of Lala Lajpat Rai, killed in the police’s lathi charge as he sat for a peaceful protest against the Simon Commission’s arrival in India. His voice trembling, his eyes resolute, reminding me of Vasily Perov’s portrait of Dostoevsky, he recounts the death of his father at the hands of General Dyer in the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre. “My mother set out to find him. There was no place to step there. Do you know, the ones who fired at Dyer’s command were Indians too? Dyer stated not wanting another 1857 to happen as the reason. So if the military can kill, why can’t the people?”

Just then, their conversation is interrupted by sharp raps at a door announcing the arrival of policemen wanting to search hostel rooms. They blindly try to hide the gun, Riaz urging Baldev to surrender, until the brilliant final scene– marked by a loud kick at the door and cut– darkness.

The open-ended conclusion also leaves a question for the audience– what is revolution? Is it a theatrical display, or is it something that must be radical? Is murdering for revolution really worth it, when one tyrant can skilfully be replaced by another, and is dismantling the system much more complex? You’re allowed to reach your own conclusions as a viewer.

Every minute of the play reminded me of why modern theatre, the likes of Ibsen (The Doll’s House), Shaw (Pygmalion) and Strindberg (Miss Julie), is so significant– it takes the simplicity of setting and a natural cadence to dialogue to create a setting and a story that resonates for centuries. That is what Anarkali Se Agey represented too. The humour is almost juvenile, the one that you share with your friends as an adolescent, and the dialect is sharp and crisp, very accurately portraying the nuances of Indian Punjabi dialects. It’s a delight to watch, away from the conventional stories we see on screen and stage, and brilliantly written and directed.

I had the chance to talk to the legendary Mr. Salman Shahid after the play. His review captured what I had on my mind as well. “Sara, I think it is incredible what they have managed to achieve in this small, minimal space. Plus, young people writing an original script, and you’re learning about original, recent history in a manner that you never do in your books. At least I have not, so it was refreshing to see another perspective on it. It was brilliantly done.”

The humour is almost juvenile, the one that you share with your friends as an adolescent, and the dialect is sharp and crisp, very accurately portraying the nuances of Indian Punjabi dialects. It’s a delight to watch, away from the conventional stories we see on screen and stage, and brilliantly written and directed.

In talks with the cast and the writer of the play, they gave me more insight into their work. All three of them are NAPA (National Academy of Performing Arts) graduates, with Fawad being a senior who graduated from NAPA’s first batch, and has been actively trying to direct original scripts and works, as well as writing and acting. Rayyan and Abdul Rehman are batchmates and good friends, which certainly explains the wonderful chemistry on stage, and are also both involved in acting, writing and directing. When I asked Abdul Rehan, who wrote the play and also acted the part of Baldev Singh, about his opinion on violence as an act of revolution, he quoted Paulo Freire’s “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” to me. I ended up reading it later–

“With the establishment of a relationship of oppression, violence has already begun. Never in history is violence initiated by the oppressed. How could they be initiators, if they were themselves an act of violence?” I agreed, quoting Arundhati Roy’s words about non-violence being a piece of theatre– “what can you do when you have no audience?”

I also talked to him about how he mastered the nuances of the Punjabi dialect, and he stated that his grandmother had spoken the Chandigarh dialect of Punjabi, very similar to the dialect spoken at the time in Pakistan and Lahore, so he ended up working to try and perfect the Chandigarh dialect for his character, Baldev, in the play. As for the humour, Rayyan, Fawad and Abdul Rehman agreed that it naturally seeped into the dialogues. “Well, would the play really be accurate if a Punjabi man was not the most humorous of the duo, even in the face of trouble?”

Working and rewiring the play multiple times since its inception had also been a task– I mentioned a previous review stating the ending had been too abrupt with a monologue to top it off. “You have really done your research,” he laughed, “but yes, you’re talking about a very early version we did at the Arts Council. We have very meticulously worked it through since then.”

On an ending note, they gave very wise bits of advice to anyone hoping to take their play on stage and to represent it at several places– “Make plays that are shorter, and easier to travel. Have a set that is minimalistic, so even if you’re on a stage that lacks the equipment you want to add to the setting, you can work without it, without taking from the integrity of the script.”

This play was extremely insightful, light-hearted at times, and dripping heavy with grief at others, holding a mirror to the current times, and often, laden with foreshadowing. I can only hope that mainstream media can divorce itself from continually representing stories that have been seen over and again, and bring nothing of substance, to more stories that feature our history and the complexities and nuances of being human. The excellent story-telling, the natural cadence of the dialogues and setting, as well as the chemistry between the actors made for a successful production– one that I hope finds many more venues.