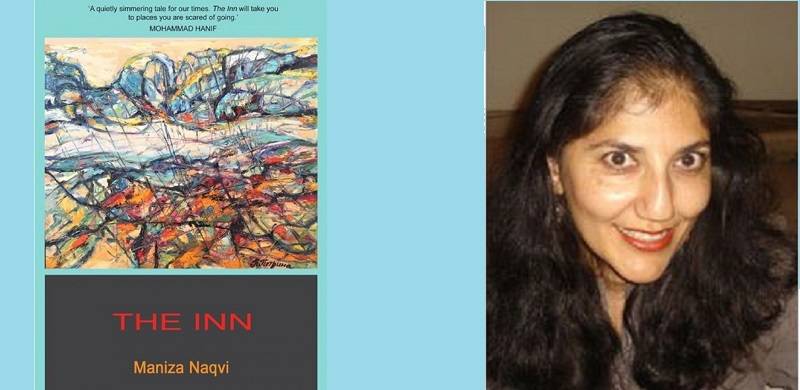

From reluctant initial steps towards finding its own idiom as well as a politics that picks itself up and graduates from abject apologia to informed introspection to bold questioning, the Pakistani novel has taken important strides in desirable directions. Having assessed and reconciled to an appreciable extent their own identity while living on foreign shores, Pakistani writers are now engaging much more self-assuredly with how the world – essentially the West that controls trade, aid, and publishing – often chooses to define and stereotype us. Also, how such categorising and judgmental behavior often hides behind veneers of noble intentions, political correctness or old-fashioned duplicity. Finally, how it all reveals the ignorance, insecurities, paradoxes, and at times, agendas, of those who categorise and judge. The Inn from Maniza Naqvi comes to us as an excellent representative of this advanced phase of political consciousness and contestation in Pakistani fiction. It’s a novel that meets the necessary criteria of a good read, but more importantly it provokes questions and provides insights that can only be offered by someone with nuanced multi-cultural sensitivity, which Naqvi fully possesses.

The protagonist is a Washington DC-based Pakistani origin doctor who escapes regularly to the pleasant Virginia countryside to take breaks from his routine. However, these are not mere mindless escapades, and mercifully, the gent thinks deeply and questions the world around him rather than holding forth on all things based on rudimentary understanding of how societies, politics and cultures work. Understandably, therefore, his response to stereotyping, mischaracterisation and casual racism isn’t sheepish and submissive. Instead, his encounters with a whole host of characters during his retreats give rise to engagements where he draws on his rich multicultural experiences and assessments to invigorate conversations that are vital to our times. Race, class, nationality and background remain, as we know, extraordinarily important distinguishing as well as discriminating factors, even as we move towards the second quarter of the 21st century. Naqvi’s novel provides multiple instances of how good fiction can continue telling an engaging story whilst exploring multiple sombre themes and issues that influence and impact millions of lives, mostly for the worse.

A vast and growing chasm in our society is based on language. Whereas our literary giants of the latter half of the previous century – Qurat-ul-Ain Haider, Faiz, Rashid, Faraz, Ashfaq Ahmad, Abdullah Hussain, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi and so many others – were cosmopolitan as well as locally grounded, multi-lingual, well-versed in global literature and at ease with the civilisational and cultural spectrum, we today face an unenviable situation.

With exceptions, those writing in English approach local languages, literature and lore with the reticence and awkwardness of foreigners on a summer of cultural discovery, whereas those writing in Urdu and regional languages – again exceptions notwithstanding – hide their inadequacy in English and thereby weak exposure to global literature (our translation culture and output is not what it used to be) with insularity and resentment against writing in English. Both suffer not only in terms of losing out on much that would enhance their own growth and understanding to become better writers but also because they increasingly don’t talk to each other anymore.

Naqvi on the other hand – both due to her lineage from an august family of great literary and artistic high achievement and her own life-long passion for and commitment to books and writing – possesses the vast appreciation of and comfortable coexistence with Eastern and Western cultures to be able to convincingly create a character like the protagonist. Her own progression as a person and a writer – through her early novels to her later writing as well as her tremendous contributions to the Pakistani literary scene through successful initiatives such as the revival of the iconic Pioneer Book House in Karachi and the pioneering launch of e-publishing through The Little Book Company – is much on display in what is a highly well-crafted novel in terms of technique as well as thought. In books such as these it is easy to fall prey to becoming preachy and didactic or for the narrative voice to utterly overwhelm plot and characterization. But Naqvi is an adept practitioner and steers clear of these traps, even when her inherent intent is to write a book of ideas of our times. Like all good literature this can’t and shouldn’t be typecast as a Pakistani novel written by an expat. For indeed it ought to resonate with many across different nationalities and cultures who have been caught up in the tumultuous events and experiences of the past quarter of a century that have formulated global attitudes and policies. Especially when it comes to defining and ‘othering’ those who belong to different milieus. In that sense, some of the preoccupations, conversations and observations here reminded me of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s excellent Americanah which, though from a Nigerian perspective, is again deeply universal in its relevance and outlook.

Quite apart from being a seasoned international social protection and development professional, writer, publisher, and bookseller, over the years Naqvi has also played the commendable roles of an astute commentator on – and champion of – Pakistani fiction in English. Her own highly informed sense of where it is headed, what it has gained and what it now aspires to, appears to have influenced her decision to write this unusual book, so different from past attempts at appreciating the Pakistani emigrant experience. Also, so much bolder.

The desi protagonist is no longer just being questioned but is now the questioner, who doesn’t shy away from asking probing and uncomfortable questions. That it offers a rich tapestry of cultural, historical, and literary references – reflecting Naqvi’s keen observation and careful reflection – make both the narrative as well as the protagonist highly compelling. Prejudice and alienation remain two of the biggest banes of humankind even after all these millennia. The Inn is a highly intelligent and lyrical exploration of these themes and tells a story that all serious readers of literature ought to read.w

The protagonist is a Washington DC-based Pakistani origin doctor who escapes regularly to the pleasant Virginia countryside to take breaks from his routine. However, these are not mere mindless escapades, and mercifully, the gent thinks deeply and questions the world around him rather than holding forth on all things based on rudimentary understanding of how societies, politics and cultures work. Understandably, therefore, his response to stereotyping, mischaracterisation and casual racism isn’t sheepish and submissive. Instead, his encounters with a whole host of characters during his retreats give rise to engagements where he draws on his rich multicultural experiences and assessments to invigorate conversations that are vital to our times. Race, class, nationality and background remain, as we know, extraordinarily important distinguishing as well as discriminating factors, even as we move towards the second quarter of the 21st century. Naqvi’s novel provides multiple instances of how good fiction can continue telling an engaging story whilst exploring multiple sombre themes and issues that influence and impact millions of lives, mostly for the worse.

A vast and growing chasm in our society is based on language. Whereas our literary giants of the latter half of the previous century – Qurat-ul-Ain Haider, Faiz, Rashid, Faraz, Ashfaq Ahmad, Abdullah Hussain, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi and so many others – were cosmopolitan as well as locally grounded, multi-lingual, well-versed in global literature and at ease with the civilisational and cultural spectrum, we today face an unenviable situation.

With exceptions, those writing in English approach local languages, literature and lore with the reticence and awkwardness of foreigners on a summer of cultural discovery, whereas those writing in Urdu and regional languages – again exceptions notwithstanding – hide their inadequacy in English and thereby weak exposure to global literature (our translation culture and output is not what it used to be) with insularity and resentment against writing in English. Both suffer not only in terms of losing out on much that would enhance their own growth and understanding to become better writers but also because they increasingly don’t talk to each other anymore.

Naqvi on the other hand – both due to her lineage from an august family of great literary and artistic high achievement and her own life-long passion for and commitment to books and writing – possesses the vast appreciation of and comfortable coexistence with Eastern and Western cultures to be able to convincingly create a character like the protagonist. Her own progression as a person and a writer – through her early novels to her later writing as well as her tremendous contributions to the Pakistani literary scene through successful initiatives such as the revival of the iconic Pioneer Book House in Karachi and the pioneering launch of e-publishing through The Little Book Company – is much on display in what is a highly well-crafted novel in terms of technique as well as thought. In books such as these it is easy to fall prey to becoming preachy and didactic or for the narrative voice to utterly overwhelm plot and characterization. But Naqvi is an adept practitioner and steers clear of these traps, even when her inherent intent is to write a book of ideas of our times. Like all good literature this can’t and shouldn’t be typecast as a Pakistani novel written by an expat. For indeed it ought to resonate with many across different nationalities and cultures who have been caught up in the tumultuous events and experiences of the past quarter of a century that have formulated global attitudes and policies. Especially when it comes to defining and ‘othering’ those who belong to different milieus. In that sense, some of the preoccupations, conversations and observations here reminded me of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s excellent Americanah which, though from a Nigerian perspective, is again deeply universal in its relevance and outlook.

Quite apart from being a seasoned international social protection and development professional, writer, publisher, and bookseller, over the years Naqvi has also played the commendable roles of an astute commentator on – and champion of – Pakistani fiction in English. Her own highly informed sense of where it is headed, what it has gained and what it now aspires to, appears to have influenced her decision to write this unusual book, so different from past attempts at appreciating the Pakistani emigrant experience. Also, so much bolder.

The desi protagonist is no longer just being questioned but is now the questioner, who doesn’t shy away from asking probing and uncomfortable questions. That it offers a rich tapestry of cultural, historical, and literary references – reflecting Naqvi’s keen observation and careful reflection – make both the narrative as well as the protagonist highly compelling. Prejudice and alienation remain two of the biggest banes of humankind even after all these millennia. The Inn is a highly intelligent and lyrical exploration of these themes and tells a story that all serious readers of literature ought to read.w