Mammoth exhibitions are increasing steadily with the growing popularity such huge international group shows as ‘Pearls of Peace’, the ‘First International Watercolour Biennale’ held in Jamshoro and Karachi not long ago, with 271 exhibits from 89 countries; and more recently a show including works by 20 Pakistani and 20 Portuguese watercolourists held at the Foundation for Museum of Modern Art in DHA. This is a travelling show, its itinerary including Rome, Karachi (Clifton Art Gallery), Jamshoro, Portugal and finally Fabriano, Italy.

Extensive solo exhibitions, too, are frequently held by such renowned and frequently awarded painters as Ghulam Mustafa, who delighted the public recently by displaying his oil-on-canvas show of 25 pieces titled ‘Landscapes of Pakistan’ at Clifton Art Gallery. As general secretary of the Punjab Artists’ Association, he encourages young artists and works unceasingly to see that all find a place in the Association’s annual exhibition in the Alhamra Cultural Complex, Lahore. Then, as to his endless list of prizes and awards, amongst the highest is the President’s Pride of Performance Award. His list of exhibitions, mostly in India and Pakistan, is also endless. Besides his skillful work with cityscapes, he has taken inspiration from nature, and one finds in his landscapes wonder and undeniable magnificence in his unspoiled views of majestic mountains, changing skies and rich colours. The well known painter, teacher, art critic and writer Mian Ijaz-ul-Hassan may be quoted as saying, however, “In the present works there is greater reliance on tone rather than on livid conflict of light and colour... The heavy textures are replaced by smooth surfaces glazed by soft tints of light that help Mustafa to establish a greater illusion of space. The eye can now with less strain retreat to the distant hills, recede along formations of trees or (concerning cityscapes), peer at monuments through wooden balconies... (These things) seem to point towards a new direction being pondered over by him.”

He belongs to the ‘plein air’ school - a French term meaning ‘open air’, particularly applied to painting outdoors, also referred to as ‘peinture sur le motif,’ and describing ‘what the eye actually sees at the time of painting.’ Artists have for long painted outdoors, but in the mid-19th century its popularity increased with the introduction of paint in tubes. French Impressionists advocated ‘plein air’ painting, and often Monet, Pissaro and Pierre-August Renoir, for example, followed this style in the diffuse light of a large white umbrella, while even in the New World, in places such as the Maui School of Art in Lahaina, Hawaii, ‘plein air’ painting is popular.

The history of painting is an ongoing river of creativity that continues into the 21st century. However, even as landscape became acceptable as a subject in the 17th century, they were still often created as settings for Biblical, mythical or historical scenes. But after the generations of Virgil’s influence on the popularity of Arcadia as a location, in the late 18th century, Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes changed the tide for landscapes with his book, Elements de Perspective Practique, which emphasised that, “Landscape must be based on the study of real nature.” Its success inspired the creation of a prize for landscapes in 1817. Then in the 19th century, landscape photography appeared, which as it gained acceptance, influenced greatly the landscape painter’s compositional choices, while in the 20th century we find the definition of ‘landscape’ including concepts like urban landscape, cultural landscape, industrial landscape and landscape architecture.

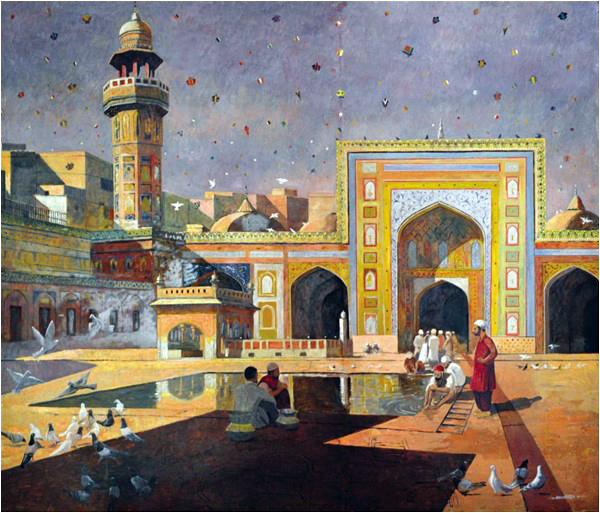

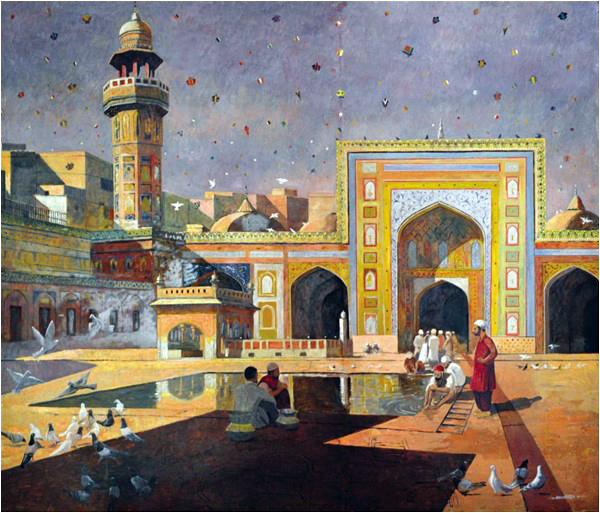

As for his own work, the artist is a familiar sight as he sits here and there in his beloved Lahore, painting with consummate skill its various buildings, its mosques and its bazaars. One of his favourite pieces is his rendering of Wazir Khan’s Masjid (in fact Wazir Khan owned substantial amounts of property near the Delhi Gate in that city). The aforementioned masjid, for those viewers not familiar with the city, was built during the reign of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, with construction beginning in 1634 and ending in 1641. It is renowned for its intricate faience work (known as kashi-kari). Ghulam has given us a faithful picture of the masjid, with all its beautiful features including its large, Timurid-style iwan flanked by 2 projecting balconies. Above the iwan is an Arabic declaration of faith written in intricate tile-work. Apart from all this, and his faithful colouring and skillful use of shadows, the artist has embellished the view with a sky filled with colourful kites, whilst pigeons strut and flutter about near the large pool.

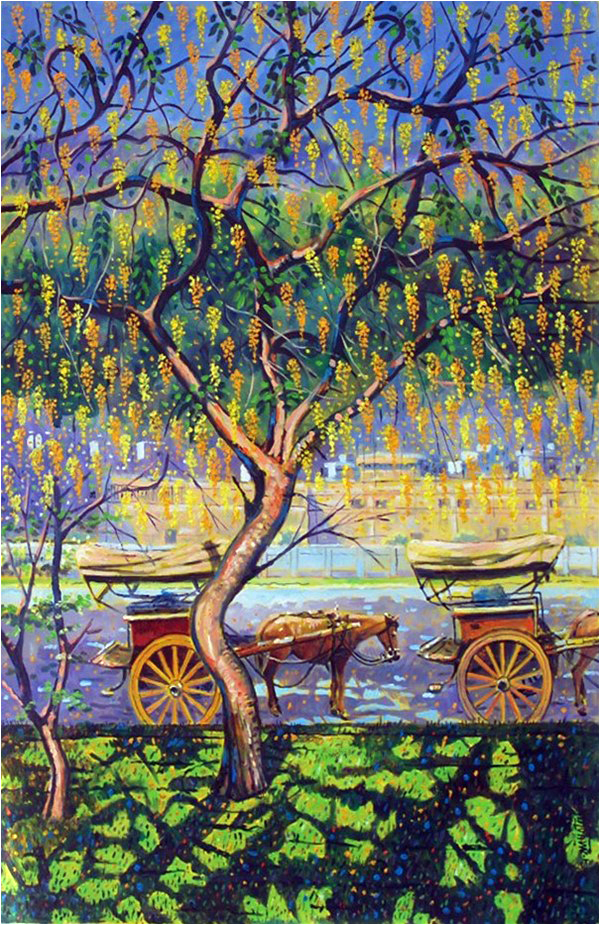

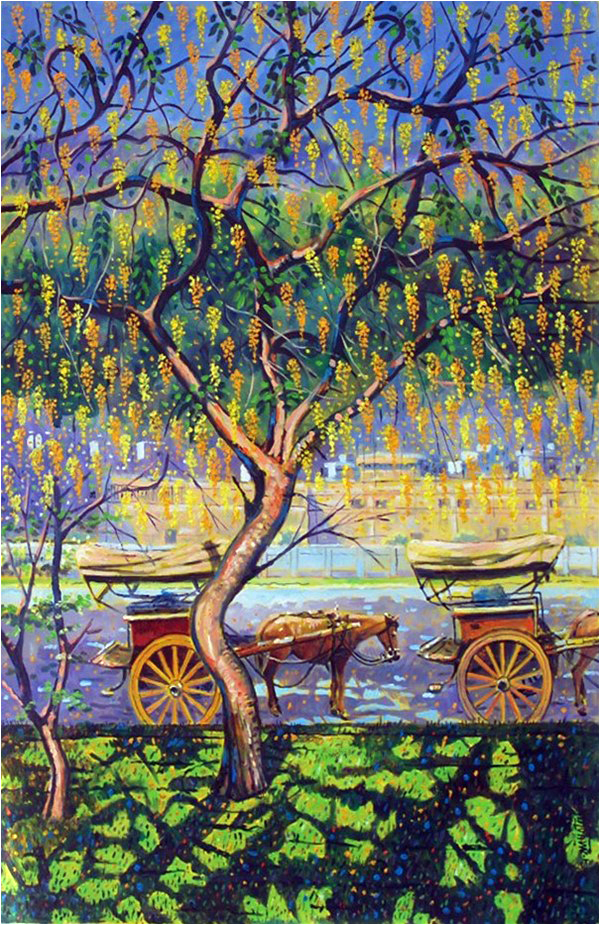

Bringing to mind the horse and carriage days of yore is a delightful study of a town or city street dominated by a large Indian laburnum tree in full bloom. The artist’s skillful use of shadow on the gracefully curving, slender trunk and branches is particularly attractive, as are the shadow patterns cast on the grass below and on the street. Meanwhile a couple of horses wait patiently, ‘sans drivers, sans passengers, sans feed bags and sans all’ in the street below, the woodwork and other features of the tongas – being mainly yellow, like the buildings across the street – help to create a harmonious and memorable picture. This is unlike the dusty atmosphere in pictures of far-off villages, though these pictures also have a certain charm. Interestingly, the laburnum is one of the most feared ‘poison plants’, though it does not justify its reputation.

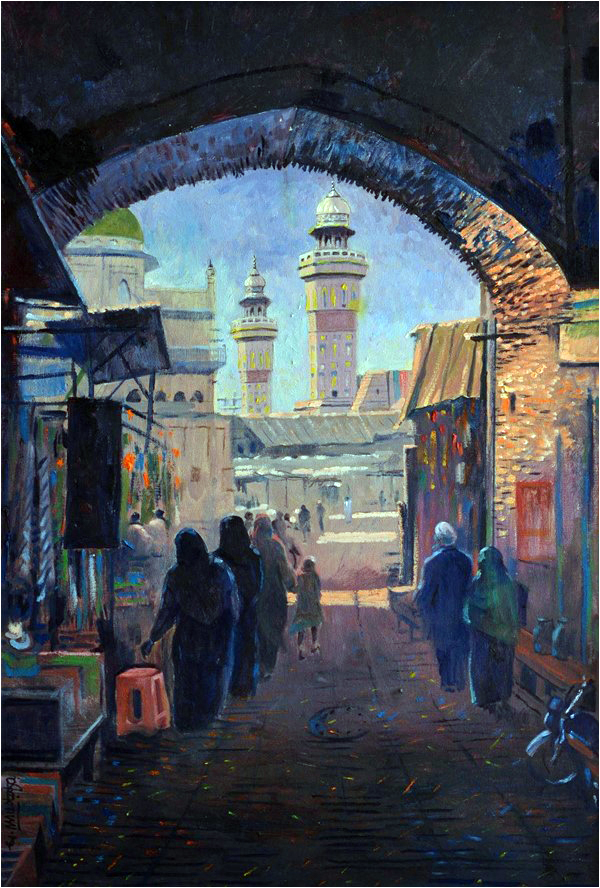

Also rather less formal are Ghulam’s numerous bazaar pictures, some of them showing dark alleys with their usual fascinating aspects: with shops and merchandise well displayed, whilst kites add their decorative touch and birds fly about far above, near where the sun gives its light to the upper storeys of buildings close to the ends of the alleys, and human figures may be seen indistinctly. An attractive, colourful bazaar fascinates us with its more generous allowance of light. Elsewhere we are fascinated by multicoloured, beautiful architectural details, such as lattice-work and arches, with customers wandering around down below in the sunlight. Ghulam, as a faithful ‘plein air’ adherent, has certainly painted “what the eye sees,” though these and other such paintings seem to belong to the days before kites and their accoutrements were banned.

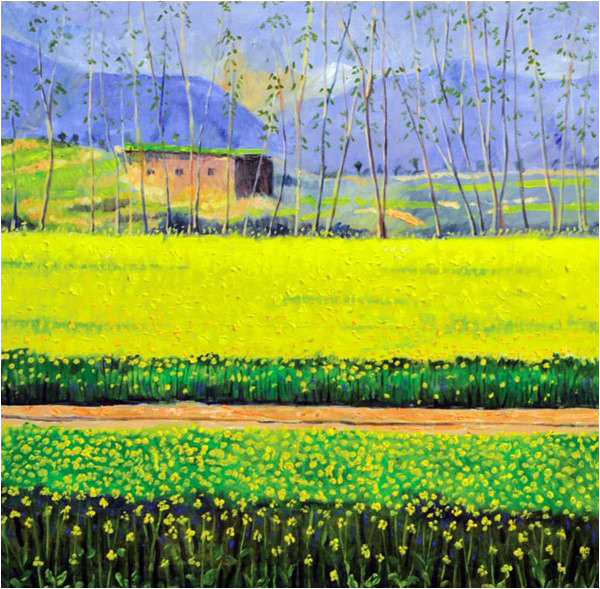

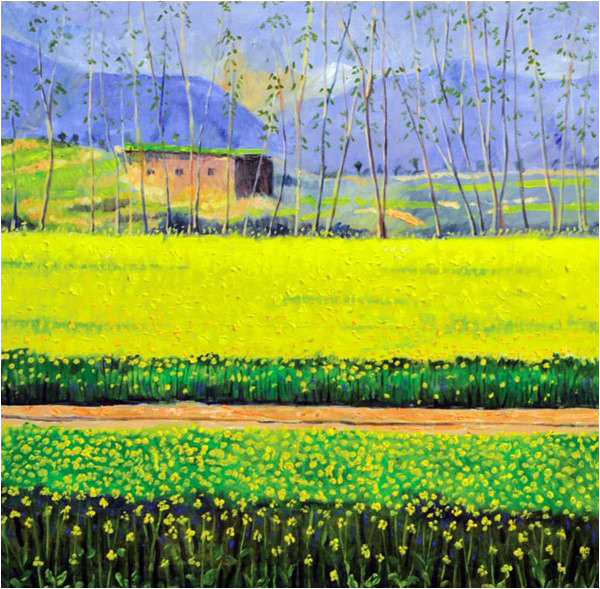

Amongst his village pictures, some showing signs of human habitation, some without, the artist has presented a number of Punjabi villages where mustard flowers – with their impressive history – dominate the scene. As the eye follows the neat arrangement of a certain piece, one is treated firstly to the sight of closely planted single blooms, whilst across the road is a regular, lucrative forest of yellow-flowering plants, terminated by a row of slender trees. Then, is it a cottage or a barn that follows, settled on a slight rise, where the patchy colours of the meadow add variety? The depth of field is skillfully composed, with a thin line of somewhat bulky, small trees leading the eye to the pleasing blue curves of the hills topped by a lilac sky. Buyiglikesfast

Mustafa is greatly attracted by the colour combination of mustard and lilac, and this we see in several of his mustard-producing villages – one in particular a collection of square mud huts, with such homely features as a line of clothes hung out to dry. Here and there are judiciously placed trees, including a line of stoutly formed trees in the background, beneath a lilac sky, whose colour deepens as the eye rises. It is said that Ghulam Sahib frequently spent the day in the company of Professor Anna Molka, one of the founders of the Fine Arts Department of Punjab University, painting famous spots in Lahore or venturing far into the countryside to capture nature’s beauty. Could it be that in such a village and its environs they were accosted by a band of heavily armed brigands on horseback, hostile fellows who were speedily mollified and dispersed by Professor Anna’s calm and courteous manner?

Mustard comes to the table as spice or oil, and the leaves can be eaten as mustard greens. Though making an attractive picture, they have an impressive history, some varieties being well established crops in Hellenistic and Roman times, whilst the Encyclopaedia Britannica states that it was grown by the Indus civilisation in 2500 to 1700 B.C. Some of the earliest references to mustard and its uses date back to the Sumerian and Sanskrit texts from 3000 B.C.

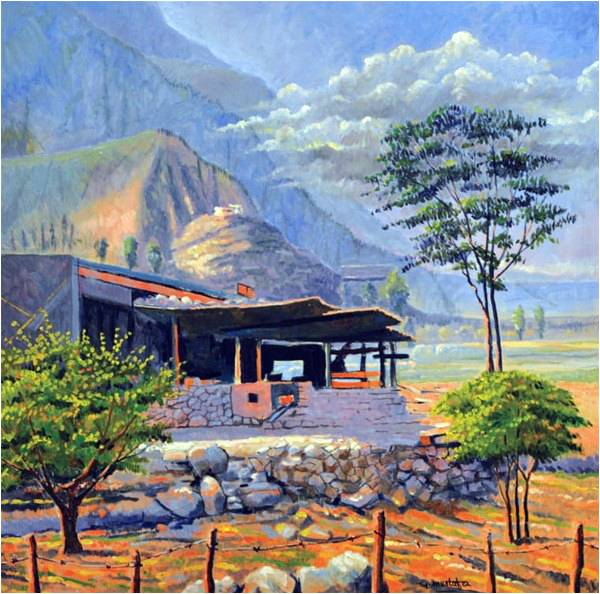

Perhaps a more likely spot for the appearance of brigands would be the sparsely populated village in the Gilgit region surrounded by majestic mountains, with their powerful diagonal slopes, typical of the Gilgit landscape, set under a graceful cloud formation. This is a picture with considerable impact, the main feature besides the clouds and dramatic blue-grey slopes being the large tea stall in the foreground, with its surrounding, neatly planted trees set on a tract of yellowish, barren land. Built of stones and partly of concrete, and with wooden supports for the haphazardly built verandah, it shows no sign of habitation, or indeed of any sort of activity at that particular time. On a distant hill is what appears to be a pukkah dwelling. This is an irresistible location, not only for landscape artists and photographers, but also for brigands and their nefarious deeds.

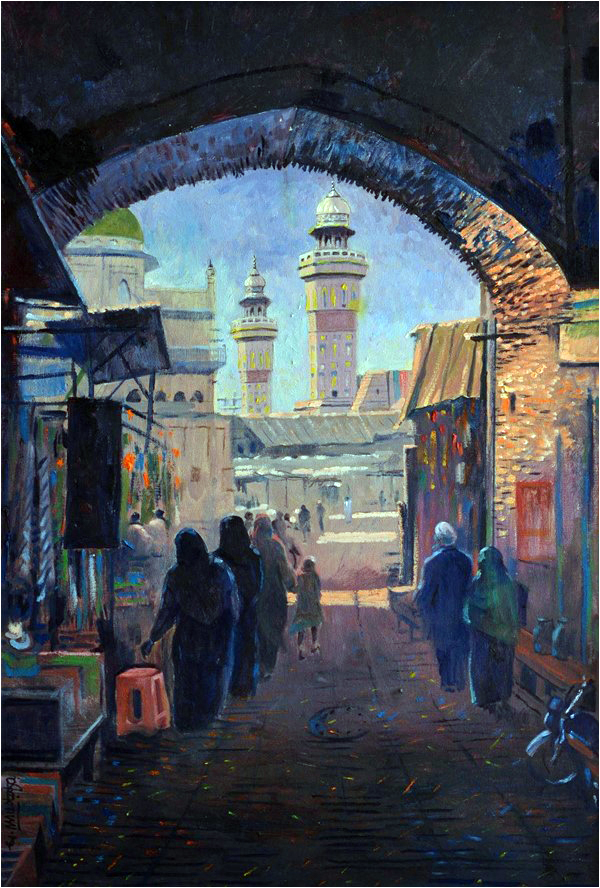

Most of Ghulam’s works in this show are painted in bright colours, an exception being his excellent rendering of the main gate of Wazir Khan’s Masjid. The striking contrast between areas of light nearer the masjid and the shadowy area within the gate is really impressive, though we can also see plainly individual red bricks where the sunlight strikes them, as a contrast to the silhouetted figures passing through, presumably to the masjid. The dim light identifies one or two stalls set up within the dark confines of this passage, but up ahead in the remaining sunlight are the clear images of two of the masjid’s minarets, beautifully designed, each having a height of 33 metres. A city of historic gates and mosques, owing much of its beauty to the individual rulers who have left their signatures upon it: that is Lahore. And we shall always be grateful to Ghulam Mustafa, the artist who has fascinated us with these images of Lahore and other picturesque spots.

Extensive solo exhibitions, too, are frequently held by such renowned and frequently awarded painters as Ghulam Mustafa, who delighted the public recently by displaying his oil-on-canvas show of 25 pieces titled ‘Landscapes of Pakistan’ at Clifton Art Gallery. As general secretary of the Punjab Artists’ Association, he encourages young artists and works unceasingly to see that all find a place in the Association’s annual exhibition in the Alhamra Cultural Complex, Lahore. Then, as to his endless list of prizes and awards, amongst the highest is the President’s Pride of Performance Award. His list of exhibitions, mostly in India and Pakistan, is also endless. Besides his skillful work with cityscapes, he has taken inspiration from nature, and one finds in his landscapes wonder and undeniable magnificence in his unspoiled views of majestic mountains, changing skies and rich colours. The well known painter, teacher, art critic and writer Mian Ijaz-ul-Hassan may be quoted as saying, however, “In the present works there is greater reliance on tone rather than on livid conflict of light and colour... The heavy textures are replaced by smooth surfaces glazed by soft tints of light that help Mustafa to establish a greater illusion of space. The eye can now with less strain retreat to the distant hills, recede along formations of trees or (concerning cityscapes), peer at monuments through wooden balconies... (These things) seem to point towards a new direction being pondered over by him.”

Most of Ghulam's works in this show are painted in bright colours, an exception being his excellent rendering of the main gate of Wazir Khan's Masjid

He belongs to the ‘plein air’ school - a French term meaning ‘open air’, particularly applied to painting outdoors, also referred to as ‘peinture sur le motif,’ and describing ‘what the eye actually sees at the time of painting.’ Artists have for long painted outdoors, but in the mid-19th century its popularity increased with the introduction of paint in tubes. French Impressionists advocated ‘plein air’ painting, and often Monet, Pissaro and Pierre-August Renoir, for example, followed this style in the diffuse light of a large white umbrella, while even in the New World, in places such as the Maui School of Art in Lahaina, Hawaii, ‘plein air’ painting is popular.

The history of painting is an ongoing river of creativity that continues into the 21st century. However, even as landscape became acceptable as a subject in the 17th century, they were still often created as settings for Biblical, mythical or historical scenes. But after the generations of Virgil’s influence on the popularity of Arcadia as a location, in the late 18th century, Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes changed the tide for landscapes with his book, Elements de Perspective Practique, which emphasised that, “Landscape must be based on the study of real nature.” Its success inspired the creation of a prize for landscapes in 1817. Then in the 19th century, landscape photography appeared, which as it gained acceptance, influenced greatly the landscape painter’s compositional choices, while in the 20th century we find the definition of ‘landscape’ including concepts like urban landscape, cultural landscape, industrial landscape and landscape architecture.

Mustafa is greatly attracted by the colour combination of mustard and lilac, and this we see in several of his mustard-producing villages

As for his own work, the artist is a familiar sight as he sits here and there in his beloved Lahore, painting with consummate skill its various buildings, its mosques and its bazaars. One of his favourite pieces is his rendering of Wazir Khan’s Masjid (in fact Wazir Khan owned substantial amounts of property near the Delhi Gate in that city). The aforementioned masjid, for those viewers not familiar with the city, was built during the reign of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, with construction beginning in 1634 and ending in 1641. It is renowned for its intricate faience work (known as kashi-kari). Ghulam has given us a faithful picture of the masjid, with all its beautiful features including its large, Timurid-style iwan flanked by 2 projecting balconies. Above the iwan is an Arabic declaration of faith written in intricate tile-work. Apart from all this, and his faithful colouring and skillful use of shadows, the artist has embellished the view with a sky filled with colourful kites, whilst pigeons strut and flutter about near the large pool.

Bringing to mind the horse and carriage days of yore is a delightful study of a town or city street dominated by a large Indian laburnum tree in full bloom. The artist’s skillful use of shadow on the gracefully curving, slender trunk and branches is particularly attractive, as are the shadow patterns cast on the grass below and on the street. Meanwhile a couple of horses wait patiently, ‘sans drivers, sans passengers, sans feed bags and sans all’ in the street below, the woodwork and other features of the tongas – being mainly yellow, like the buildings across the street – help to create a harmonious and memorable picture. This is unlike the dusty atmosphere in pictures of far-off villages, though these pictures also have a certain charm. Interestingly, the laburnum is one of the most feared ‘poison plants’, though it does not justify its reputation.

Also rather less formal are Ghulam’s numerous bazaar pictures, some of them showing dark alleys with their usual fascinating aspects: with shops and merchandise well displayed, whilst kites add their decorative touch and birds fly about far above, near where the sun gives its light to the upper storeys of buildings close to the ends of the alleys, and human figures may be seen indistinctly. An attractive, colourful bazaar fascinates us with its more generous allowance of light. Elsewhere we are fascinated by multicoloured, beautiful architectural details, such as lattice-work and arches, with customers wandering around down below in the sunlight. Ghulam, as a faithful ‘plein air’ adherent, has certainly painted “what the eye sees,” though these and other such paintings seem to belong to the days before kites and their accoutrements were banned.

Amongst his village pictures, some showing signs of human habitation, some without, the artist has presented a number of Punjabi villages where mustard flowers – with their impressive history – dominate the scene. As the eye follows the neat arrangement of a certain piece, one is treated firstly to the sight of closely planted single blooms, whilst across the road is a regular, lucrative forest of yellow-flowering plants, terminated by a row of slender trees. Then, is it a cottage or a barn that follows, settled on a slight rise, where the patchy colours of the meadow add variety? The depth of field is skillfully composed, with a thin line of somewhat bulky, small trees leading the eye to the pleasing blue curves of the hills topped by a lilac sky. Buyiglikesfast

Mustafa is greatly attracted by the colour combination of mustard and lilac, and this we see in several of his mustard-producing villages – one in particular a collection of square mud huts, with such homely features as a line of clothes hung out to dry. Here and there are judiciously placed trees, including a line of stoutly formed trees in the background, beneath a lilac sky, whose colour deepens as the eye rises. It is said that Ghulam Sahib frequently spent the day in the company of Professor Anna Molka, one of the founders of the Fine Arts Department of Punjab University, painting famous spots in Lahore or venturing far into the countryside to capture nature’s beauty. Could it be that in such a village and its environs they were accosted by a band of heavily armed brigands on horseback, hostile fellows who were speedily mollified and dispersed by Professor Anna’s calm and courteous manner?

Mustard comes to the table as spice or oil, and the leaves can be eaten as mustard greens. Though making an attractive picture, they have an impressive history, some varieties being well established crops in Hellenistic and Roman times, whilst the Encyclopaedia Britannica states that it was grown by the Indus civilisation in 2500 to 1700 B.C. Some of the earliest references to mustard and its uses date back to the Sumerian and Sanskrit texts from 3000 B.C.

Perhaps a more likely spot for the appearance of brigands would be the sparsely populated village in the Gilgit region surrounded by majestic mountains, with their powerful diagonal slopes, typical of the Gilgit landscape, set under a graceful cloud formation. This is a picture with considerable impact, the main feature besides the clouds and dramatic blue-grey slopes being the large tea stall in the foreground, with its surrounding, neatly planted trees set on a tract of yellowish, barren land. Built of stones and partly of concrete, and with wooden supports for the haphazardly built verandah, it shows no sign of habitation, or indeed of any sort of activity at that particular time. On a distant hill is what appears to be a pukkah dwelling. This is an irresistible location, not only for landscape artists and photographers, but also for brigands and their nefarious deeds.

Most of Ghulam’s works in this show are painted in bright colours, an exception being his excellent rendering of the main gate of Wazir Khan’s Masjid. The striking contrast between areas of light nearer the masjid and the shadowy area within the gate is really impressive, though we can also see plainly individual red bricks where the sunlight strikes them, as a contrast to the silhouetted figures passing through, presumably to the masjid. The dim light identifies one or two stalls set up within the dark confines of this passage, but up ahead in the remaining sunlight are the clear images of two of the masjid’s minarets, beautifully designed, each having a height of 33 metres. A city of historic gates and mosques, owing much of its beauty to the individual rulers who have left their signatures upon it: that is Lahore. And we shall always be grateful to Ghulam Mustafa, the artist who has fascinated us with these images of Lahore and other picturesque spots.