It was the summer of 1996 when I started experiencing things like massive weight loss, increased thirst and unexplainable lethargy. All of these were taken as part of growing pains. So, when a random lab test revealed my fasting blood sugar to be ‘high,’ my mother thought it was a freak result and brushed it under the table – till my dad’s younger brother (also a doctor) rang our doorbell at 3 am one night to check my sugar. The result was still ‘high.’

To elaborate: equipment back then had a limited range, which should explain why these home tests didn't generate a number. The ‘high’ that we saw meant that my blood sugars at the time were at least six times the normal range. And the second home test was what got my parents acting.

I guess everyone knows the drill. Run the usual tests, give the diagnosis, and then come up with a treatment plan. At the time, a myriad of thoughts was being encountered: confusion (what is this), stress (fear of the known) and fright (am I dying). But the treatment plan in place brought on multiple realisations:

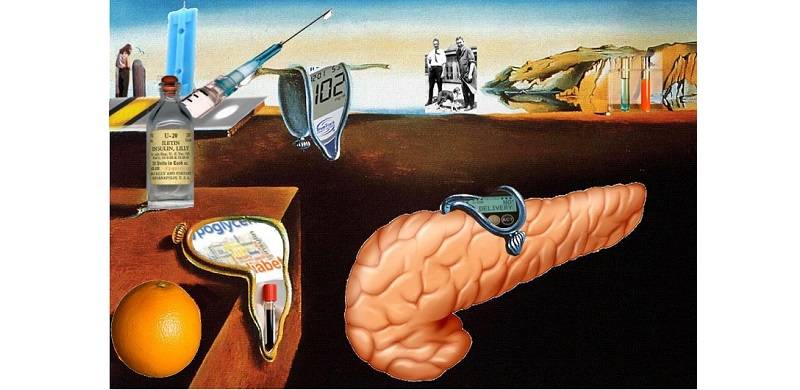

What is Type 1 diabetes? It means antibodies destroyed the beta cells of my pancreas that secrete insulin. Insulin converts food into energy and since my body doesn't naturally make its own anymore, I must inject it. I monitor my insulin to keep my sugar well in range without it going check-mate on me.

If my sugar goes low, I may pass out and would need to eat something sweet. (Oh, the joy!) And if it goes high, I'm all drowsy and slow and need to take more insulin, hydrate, and engage in some physical exertion to bring it down. That's pretty much the life of the approximately nine million people living with T1, including me.

Reporting on my disease is notoriously entertaining and I often deal with the most epic of misconceptions when talking about being a T1. Here's what I wish more people understood about what it's like to have Type 1 diabetes.

1) Part of my brain is dedicated to my blood sugar every moment, even if I'm sleeping or having fun

If you've seen The Babysitter’s Club on Netflix, there was this one episode when Stacey is nominated to be JDRF’s cover girl for the month and is honoured by them at one of its galas.

“Not being ashamed of your disease doesn’t mean you have to love it all the time. Sometimes it sucks,” Stacey said.

And it sometimes truly and really sucks. A small portion of my heart and brain always worries about my blood sugars, even if I'm trying to sleep. I’m on a thrice a day insulin regime along with oral medication to deter insulin resistance. Then there is the never-ending monitoring, precaution – the whole nine yards, basically. So, if you're wondering what a typical day in my life looks like, spoiler alert: the entertainment never ends.

2) I’ve got this, but I just want your understanding. Not your sympathy.

Despite being T1 for over 20 years now, I still get the occasional pitying, "So is your life over now or what?" look. No: it isn’t, and hey: I’ve got it.

And having Type 1 has often made me live like I'm on borrowed time: I'm an avid writer, won several accolades on this account, been on the student council while in school and am a qualified accountant, to name a few. People like me are preposterously competent at it and, by extension, often other things as well.

3) That said, if I do ask for help, you should probably consider it at least a minor emergency

I tend to always come prepared. I’ve survived several treks and road trips and camping trips, with my full-scale medical kit on hand: primary medications and then the backups.

But I'm human, and I'll make an error in judgment from time to time. And my sugar often doesn't like to cooperate with my plans either. Insulin is not like some medicines; the dose changes more often than we want it to. The amount of insulin I need to inject varies – based on not just what I'm eating but how much physical activity I’ve had, my hydration levels, the humidity and even whether Venus is in retrograde. Any if I need to immediately adjust a dose, it's at best an educated guess.

So: if I foresee a situation when I realise something can potentially go wrong, I need to address my hunch before it's a catastrophe. This can mean me spacing out and not making sense, or if I ask you to grab me a juice box, I probably need it in the next 15 minutes. Stat. This can alternatively requesting ice packs to carry my insulin when I’m on an official outdoor excursion.

4) Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes are distinct illnesses, and your assumptions about both are probably wrong

Type 1 is an autoimmune disorder like Multiple Sclerosis, AIDS, hypothyroidism, etc. and Type 2 is metabolic. While they're not the same, they’re both a serious illness. The pseudo-truths and judgments people harbour about Type 2 are usually misguided and if applied to Type 1, are completely off base. And downright obnoxious.

For the record, my illness is affected by my daily lifestyle but was not brought on by my lifestyle and cannot be fixed with lifestyle changes. Yes, I'm sure it's Type 1; no, it's not just a "classification." Jamun, cinnamon and water from boiled okra will not cure me: because if I don't inject insulin, I die. Quickly.

5) I do not care about being stabbed with needles. At all. At. All.

To this day and age, I get the wide-eyed reactions to injecting my insulin – as if to say how terrible the needles must be. They come up with their thoughts on how breakthrough treatments improve control and how these treatments will be "painless" or "injection-free." HA!

Look, if the cure for diabetes was to stab myself with a rusty ice pick every hour – by God, I would do it. Don't get me wrong, repeatedly “stabbing” yourself is by any means reflexive. But it is way — way — less bad than untreated diabetes.

There are long and short-term effects of high and low blood sugars: blurry vision, fatigue, unquenchable thirst, dizziness, anxiety, rapid heartbeat, and general stupidity. Effects also experienced include dementia-like symptoms, numb feet, a lot of regurgitating followed by a coma. People seek injections for far less.

Don't look at me and say, "Oh I could never do that." Or “How do you do that?” You couldn't prick yourself with a needle to avoid violent vomit death? Of course: you could, and you would. So, please just stop.

6) I am grateful for all the treatments that are available to me today. But it is far from a cure.

We all know about how insulin was discovered by Frederick G Banting, Charles H Best and JJR Macleod at the University of Toronto in 1921 and later purified by James B Collip. It was one of the greatest medical breakthroughs in history, which went on to save millions of lives around the world.

There have been multiple advancements (in diabetes care) over time, including continuous glucose monitoring devices, and insulin patches, insulins of different types used for different treatment plans, etc. These are miracles: the product of so much hard work and innovation.

But this is far from a cure. Fortunately, though, there are hundreds of scientists looking for a cure that will (possibly) bring some semblance to normalcy in my life and a cure would enable my body to generate me new beta cells and keep my body from attacking them again. Anything that functions better than what I currently have, will be like that proverbial oasis in the desert; but till then, I'll unite with fellow T1s and try to (at least) enjoy the entertainment that people’s misconceptions about diabetes brings.

To elaborate: equipment back then had a limited range, which should explain why these home tests didn't generate a number. The ‘high’ that we saw meant that my blood sugars at the time were at least six times the normal range. And the second home test was what got my parents acting.

I guess everyone knows the drill. Run the usual tests, give the diagnosis, and then come up with a treatment plan. At the time, a myriad of thoughts was being encountered: confusion (what is this), stress (fear of the known) and fright (am I dying). But the treatment plan in place brought on multiple realisations:

- No, my life isn’t over.

- It’s a pain, by all definitions of the word pain.

- It’s terrifying, but the treatments would on average get me through the day.

What is Type 1 diabetes? It means antibodies destroyed the beta cells of my pancreas that secrete insulin. Insulin converts food into energy and since my body doesn't naturally make its own anymore, I must inject it. I monitor my insulin to keep my sugar well in range without it going check-mate on me.

If my sugar goes low, I may pass out and would need to eat something sweet. (Oh, the joy!) And if it goes high, I'm all drowsy and slow and need to take more insulin, hydrate, and engage in some physical exertion to bring it down. That's pretty much the life of the approximately nine million people living with T1, including me.

Reporting on my disease is notoriously entertaining and I often deal with the most epic of misconceptions when talking about being a T1. Here's what I wish more people understood about what it's like to have Type 1 diabetes.

1) Part of my brain is dedicated to my blood sugar every moment, even if I'm sleeping or having fun

If you've seen The Babysitter’s Club on Netflix, there was this one episode when Stacey is nominated to be JDRF’s cover girl for the month and is honoured by them at one of its galas.

“Not being ashamed of your disease doesn’t mean you have to love it all the time. Sometimes it sucks,” Stacey said.

And it sometimes truly and really sucks. A small portion of my heart and brain always worries about my blood sugars, even if I'm trying to sleep. I’m on a thrice a day insulin regime along with oral medication to deter insulin resistance. Then there is the never-ending monitoring, precaution – the whole nine yards, basically. So, if you're wondering what a typical day in my life looks like, spoiler alert: the entertainment never ends.

2) I’ve got this, but I just want your understanding. Not your sympathy.

Despite being T1 for over 20 years now, I still get the occasional pitying, "So is your life over now or what?" look. No: it isn’t, and hey: I’ve got it.

And having Type 1 has often made me live like I'm on borrowed time: I'm an avid writer, won several accolades on this account, been on the student council while in school and am a qualified accountant, to name a few. People like me are preposterously competent at it and, by extension, often other things as well.

3) That said, if I do ask for help, you should probably consider it at least a minor emergency

I tend to always come prepared. I’ve survived several treks and road trips and camping trips, with my full-scale medical kit on hand: primary medications and then the backups.

But I'm human, and I'll make an error in judgment from time to time. And my sugar often doesn't like to cooperate with my plans either. Insulin is not like some medicines; the dose changes more often than we want it to. The amount of insulin I need to inject varies – based on not just what I'm eating but how much physical activity I’ve had, my hydration levels, the humidity and even whether Venus is in retrograde. Any if I need to immediately adjust a dose, it's at best an educated guess.

So: if I foresee a situation when I realise something can potentially go wrong, I need to address my hunch before it's a catastrophe. This can mean me spacing out and not making sense, or if I ask you to grab me a juice box, I probably need it in the next 15 minutes. Stat. This can alternatively requesting ice packs to carry my insulin when I’m on an official outdoor excursion.

4) Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes are distinct illnesses, and your assumptions about both are probably wrong

Type 1 is an autoimmune disorder like Multiple Sclerosis, AIDS, hypothyroidism, etc. and Type 2 is metabolic. While they're not the same, they’re both a serious illness. The pseudo-truths and judgments people harbour about Type 2 are usually misguided and if applied to Type 1, are completely off base. And downright obnoxious.

For the record, my illness is affected by my daily lifestyle but was not brought on by my lifestyle and cannot be fixed with lifestyle changes. Yes, I'm sure it's Type 1; no, it's not just a "classification." Jamun, cinnamon and water from boiled okra will not cure me: because if I don't inject insulin, I die. Quickly.

5) I do not care about being stabbed with needles. At all. At. All.

To this day and age, I get the wide-eyed reactions to injecting my insulin – as if to say how terrible the needles must be. They come up with their thoughts on how breakthrough treatments improve control and how these treatments will be "painless" or "injection-free." HA!

Look, if the cure for diabetes was to stab myself with a rusty ice pick every hour – by God, I would do it. Don't get me wrong, repeatedly “stabbing” yourself is by any means reflexive. But it is way — way — less bad than untreated diabetes.

There are long and short-term effects of high and low blood sugars: blurry vision, fatigue, unquenchable thirst, dizziness, anxiety, rapid heartbeat, and general stupidity. Effects also experienced include dementia-like symptoms, numb feet, a lot of regurgitating followed by a coma. People seek injections for far less.

Don't look at me and say, "Oh I could never do that." Or “How do you do that?” You couldn't prick yourself with a needle to avoid violent vomit death? Of course: you could, and you would. So, please just stop.

6) I am grateful for all the treatments that are available to me today. But it is far from a cure.

We all know about how insulin was discovered by Frederick G Banting, Charles H Best and JJR Macleod at the University of Toronto in 1921 and later purified by James B Collip. It was one of the greatest medical breakthroughs in history, which went on to save millions of lives around the world.

There have been multiple advancements (in diabetes care) over time, including continuous glucose monitoring devices, and insulin patches, insulins of different types used for different treatment plans, etc. These are miracles: the product of so much hard work and innovation.

But this is far from a cure. Fortunately, though, there are hundreds of scientists looking for a cure that will (possibly) bring some semblance to normalcy in my life and a cure would enable my body to generate me new beta cells and keep my body from attacking them again. Anything that functions better than what I currently have, will be like that proverbial oasis in the desert; but till then, I'll unite with fellow T1s and try to (at least) enjoy the entertainment that people’s misconceptions about diabetes brings.