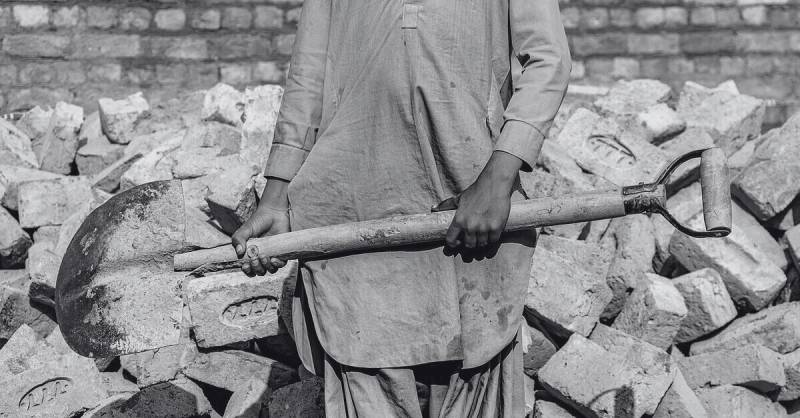

Iqbal, in his famous poem in Bal-e-Jibril, personifying God, penned:

"Find the field whose harvest is no peasant’s daily bread—

Garner in the furnace every ripening ear of wheat!"

Unfortunately, this divine message remains far from realisation, at least in Pakistan.

Since the 18th Amendment, which delegated the responsibility of formulating labor-related laws and policies to provinces, the terrain of minimum wage and health and safety has been poorly envisioned and, consequently, poorly enforced.

Initially, the Minimum Wages Ordinance (1961) was introduced to cover skilled workers. Later, the Minimum Wages for Skilled and Unskilled Workers Ordinance (1969) was enacted, to rope in unskilled workers as well. However, these laws excluded critical sectors such as public sector employees, agricultural workers, and those working for charities. Even after the 18th Amendment, ambiguities persist regarding inclusivity. Provinces now have boards to set minimum wages, but their recommendations are often disregarded, and wages are arbitrarily revised by governments, driven more by fiscal space or political expediency than genuine worker welfare.

Political gimmickry exacerbates the issue. Many legislators—an estimated 52%—are feudal landlords, deeply invested in preserving systemic inequality. Their unwillingness to contribute a fair share, as seen in the resistance to agricultural income tax and the lagging national fiscal pact, hampers progress. Meanwhile, the corporate sector fares no better. Approximately 93% of private-sector employees have not seen wage increases in the last three to four years, first due to COVID-19 and later due to stagnant economic growth.

Adding insult to injury, Pakistan has experienced a socio-economic bloodbath in recent years. With sluggish growth (a mere 3% compared to a 2.5% population growth and an annual addition of 2 million to the labor force), soaring inflation (114% food inflation over five years, and as per latest HIES, 36% of income is spent on food), and rising poverty (45.5% of the population, or 110 million people, living below the poverty line, with an increase of 31 million in the last four years, per Hafiz Pasha), the situation has become dire.

The failure to ensure a minimum standard of living for workers has far-reaching consequences: it erodes trust in institutions, fuels social unrest, and stifles economic dynamism

Spending on health and education has also declined significantly. As a percentage of GDP, combined expenditure rose from 1.53% in 2002-03 to a peak of 3.17% in 2017-18, only to fall to 2.41% in 2022-23. This drop reflects a decrease in education spending from 2.11% to 1.31%, while health spending saw a marginal rise from 1.06% to 1.10%. Signifying the state’s failure to safeguard the fundamental rights enshrined in the constitution, it forces the proles, for themselves and their families, to seek expensive educational and health solutions—if they can afford them at all.

Consequently, Pakistan's Human Development Index (HDI) ranking, by UNDP, has plummeted to 164th out of 193 countries, with an HDI of 0.540, placing it among nations with low human development. This is a stark decline from its 2020 ranking of 154th (HDI 0.557). Alarmingly, Pakistan trails behind Bangladesh (HDI 0.670, ranked 129th) and India (HDI 0.644, ranked 134th), both classified as medium-development countries.

Needless to say, without appreciated human capital, economic growth in the long run is a pipe dream. A system that perpetuates exploitation cannot expect sustainable growth or stability. Further, the failure to ensure a minimum standard of living for workers has far-reaching consequences: it erodes trust in institutions, fuels social unrest and stifles economic dynamism. It is, therefore, not just the workers who suffer but the entire economy that pays the price for systemic inequality.

These grim realities underscore the urgent need for a living wage. The Global Living Wage Coalition defines a living wage as the remuneration earned by a worker during a standard workweek in a specific location, sufficient to provide a decent standard of living for the worker and their family. Put differently, a living wage is a basic income ensuring a decent lifestyle, including nutritious diets, healthy housing, essential needs, and unforeseen expenses. Unlike minimum wage laws, which are designed to provide a baseline income, a living wage reflects the reality that wages should not merely cover survival but also enable workers to live and lead a life with dignity.

John Ryan, a moral theologian, in his book A Living Wage, postulates that the claim to a living wage is a natural right, derived from man’s rational essence and his recognition as a being of intrinsic worth. A living wage, therefore, is a fundamental natural right, rooted in the dignity of the individual and stemming from the right to subsist upon the bounty of the earth. Ryan further argues that the right to a living wage, which ensures a decent livelihood, is as essential to human well-being as subsistence or security of life and limb. This is not merely an economic or social matter but a moral imperative. Thus, when society rejects the intrinsic value of the individual and fails to recognise their entitlement to a decent livelihood, it undermines the very foundation of human rights. In support of this view, Article 23 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms that: "Everyone who works has the right to just and favorable remuneration ensuring for himself and for his family an existence worthy of human dignity.”

The outdated system of maintaining registers and wage slips for compliance needs to be replaced with modern cross-verification mechanisms

However, the global recognition of the right to a living wage does not necessarily translate into reality in many countries, including Pakistan. Despite being a signatory to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Pakistan has yet to realise the right to a living wage. According to Dawani and Sayeed, the gross living wage in rural KP, rural Sialkot, and urban Sialkot is PKR 67,035, PKR 45,718, and PKR 51,357, respectively—significantly higher than the current minimum wage for unskilled workers, which stands at PKR 36,000 in KP, and PKR 37,000 for all other provinces and Islamabad. This staggering disparity between the minimum wage and the living wage highlights the wide chasm and incongruity between the official recognition of the living wage as a fundamental human right and the lived realities of workers in Pakistan.

To move toward a living wage law as an inviolable human right, one that guarantees not only the sustenance of a decent livelihood but also provides individuals with the opportunity to develop their physical, intellectual, moral, and spiritual faculties, it is the need of the hour that a well-thought-out policy be designed and implemented in its entirety to facilitate the transition from the minimum wage to a living wage.

In practical terms, this requires a robust reform of the existing inadequate minimum wage system, ensuring the inclusion of all sectors. A detailed framework for measurement and implementation, integrated with advanced data analytics, must be developed alongside vigilant living wage boards across provinces. These boards should be well-informed about the prevailing socio-economic conditions of their respective regions. Achieving this requires strong political will.

The outdated system of maintaining registers and wage slips for compliance needs to be replaced with modern cross-verification mechanisms. Capacity building of labor inspectors through targeted training and the establishment of effective inspection protocols is crucial. Such measures would ensure systematic compliance with living wage laws as well as may help in the curtailment of the informal sector.

Apart from the government, civil society and labor unions must also mobilise to demand equitable policies, while private sector stakeholders should recognise that fair wages are not merely an obligation but an investment in human capital, productivity, and long-term profitability

Technology can play a significant role in bridging the gap. Leveraging digital tools to monitor compliance, creating transparent databases of wages, and ensuring mobile-based reporting systems for workers can eliminate many of the challenges posed by traditional methods. Additionally, digital payment platforms can be mandated for wage disbursement, reducing the risks of underpayment or non-payment altogether.

To lift workers above the poverty line, a bottom-up approach, rather than a politically motivated top-down strategy, is essential. The National Socio-Economic Registry (NSER), developed under BISP, can be leveraged to expand targeted cash transfers for workers whose wages fall below a certain threshold. Furthermore, eliminating elitist expenditures, such as around PKR 4 trillion in tax exemptions and more than a trillion in unfunded pension payments, could create fiscal space to support the nation's most vulnerable. These measures must be complemented by ensuring that workers receive fair opportunities for employment benefits, promotions, social security, and career advancement—free from discrimination based on race, gender, religion, political opinion, or any other identity marker, fostering equity and inclusivity in the labor force.

Apart from the government, civil society and labor unions must also mobilise to demand equitable policies, while private sector stakeholders should recognise that fair wages are not merely an obligation but an investment in human capital, productivity, and long-term profitability. Without collective action, the cycle of inequality will only deepen.

Lastly, merely increasing wages without addressing broader macroeconomic issues risks triggering a wage-price spiral. Prudent macroeconomic interventions are essential to ensure economic stability and growth. This includes curtailing rent-seeking expenditures, implementing efficient revenue mobilisation strategies focused on broadening the tax base rather than relying on extractive and presumptive taxation—which taxes transactions rather than income—expanding exports base, axing non-essential imports, and employing exquisite debt management.

A living wage is not just an economic imperative; it is a moral one. By prioritising the well-being of workers, Pakistan can begin to address the structural inequalities that have plagued its economy and society for decades, for poverty anywhere is a threat to prosperity anywhere.