Mirza Madhu sat on the riverbank, unravelling the thread of his thoughts as he watched the waves rise and fall until they leapt onto the shore and tickled his feet. The scattered waves arranged and rearranged themselves in patterns he could not discern but felt he knew. The river spoke to him; its presence touched him the way it touched the earth beneath his feet, the birds above his head, and the trees surrounding him. He thought to himself:

دریا ایک ایسی دھارا ہے جس میں کوئ رکاوٹ نہیں۔ وہ اگے کو بہتا چلا جاتا ہے۔

کبھی میں بھی دریا سے پوچھوں وہ اگے کو کیوں بہتا ہے؟ کیوں نہ اپنا رخ موڑ کر آسمان کو چھولے؟

(The river is such an entity which faces no obstacle and flows freely. I wish to ask the river why it simply flows forward and does not raise itself to touch the sky?)

As the waves drew closer, he at once discovered the answer. He imagined the river as a saint who did not disparage. It flows from highs to lows, into every crevice, nook, and corner. With the same abundance, the river enters the farmer’s fields and traverses the paths of the forsaken. It treats everyone’s wounds, quenches everyone’s thirst, and purifies hearts until it reunites with the sea. The river flows downstream because it brings life to everything that falls in its path. The Ravi, which once gave life to Lahore, is now pushed to the margins of the city. The way it is disappearing from the urban landscape, it is also disappearing from our collective memory. The river is a body of wonders that forms the consciousness of a society and reconnects it to its past. By severing our connection with the river and its traditions, we have forgotten ourselves.

In a dreamy state, Mirza Madhu recalled his childhood memories, which felt like a lifetime ago. He saw before him his younger self, sheepishly standing beside his father, watching Bholu Pahalwan wrestle. He felt tense when he heard the Pahalwan roaring in anger and tackling his opponent to the ground, bringing the crowd to cheer him on. It was a fearful sight, perhaps too much for his childish heart to bear.

But there was something fascinating in watching grown men graze their bodies in mud—and not just any mud, but the alluvial fertile soil of the river. He thought they were so involved in their play that they seemed somehow removed from the world, yet they carried its very pulse in the traditions they celebrated. Impressed by the Pahalwan, Madhu took a handful of mud and pressed it to his heart. He then remembered his school days at Government College, where he was a member of the rowing club.

Every Saturday, he and his friends headed to the River Ravi and spent the most relaxing hours of their day drifting along its gentle currents. Moreover, the rhythmic sound of the oars was like music to the ear. The summer breeze carried the sweet scent of honeysuckle, which reminded Madhu of his budding youth.

The collage of memories drew a portrait of an idyllic childhood untouched by the harsh realities of the world. However, those days weren’t as innocent as one would like to imagine; Madhu had his fair share of fun causing mischief with his friends.

During Akbar’s reign, the river functioned as a trade highway where numerous boats and ships would carry grains, rice, spices, and silk from Lahore to Kandahar and Central Asia

One hot summer afternoon, the boys decided to skip school and went to the river for a picnic. Upon reaching the shore, Madhu slipped off his overalls and dived into the river, calling his friends to join him. All his fatigue and the summer heat disappeared in the cool water. He swam across the river, splashing water at his friends, until finally, he found a spot to rest. He placed a mat under a Peepal tree and lay down beneath the shade of the majestic tree.

As time slowly passed by, the blazing sun became less severe, the mynahs left their nests and flew into the brilliant sky, singing in a chorus that gently put the boys to sleep. After an hour, Madhu was awakened by the sound of a bee in his ear and quickly headed home before it got dark.

Madhu snapped out of his reverie and looked up at the desolate sky, clouded by dense smog. He wondered what the sky looked like in the past and imagined hundreds of colourful kites soaring in the sky.

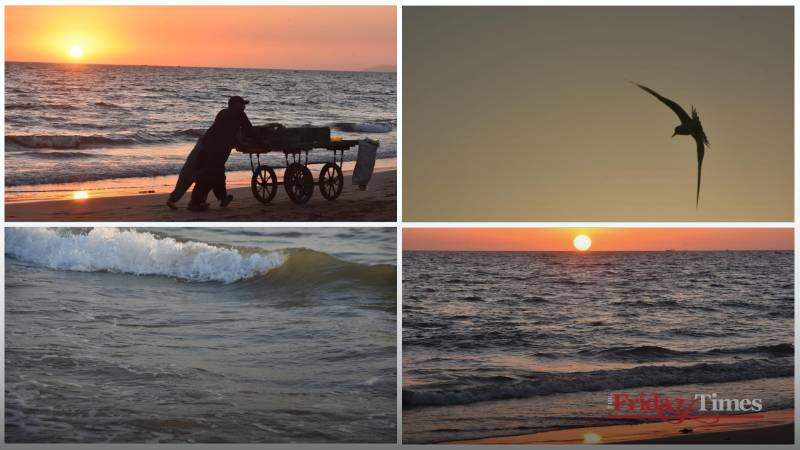

It was the year 1992; he had just received his salary and took his family out to celebrate Basant. He carried his youngest daughter on piggyback, showing her the kites flying overhead, while she, suddenly fascinated by a big pink kite, asked her father to get one for her too. Madhu, fishing out the money he had recently received, bought his daughter the loveliest kite. She was over the moon when he taught her how to fly it, but in her excitement, she let go of its string, and the kite drifted away until it became a speck in the sky. Madhu succeeded in pacifying his daughter by showing her the crowds of people who came to the Ravi to celebrate Basant.

It seemed as if all of a sudden, the river came to life; the cheerfulness was in the air as people rejoiced at the mela. Several stalls sold gol guppay, ice cream, kites, and toys. As the evening wore on, the oil lamps were lit up, and their reflection glowed into the river. With bright eyes and glowing faces, his overjoyed children got into the car, and Madhu drove back home.

Like the turbulent river, Madhu was swept into the tempest of his memories and kept recalling his past as if it would somehow inform the present. Madhu lived an ordinary life; the events that brought colour to his dull life were somehow tied to the river. He was extremely fond of the river and the beautiful memories it brought him. Those were the memories that kept him going in the darkest period of his life.

Madhu was a construction worker who worked on top of high-rise buildings, but that was only when he got work; for the most part, he remained unemployed. All his children left him as they moved abroad to study and settled down there. His youngest child and wife died in a car accident while he was busy working three shifts to pay off the bills. His loss broke his spirit to live, and he often contemplated jumping off the high-rise building. It was perhaps this anguish that brought him to the river. He hoped to make sense of his life by returning to the very source of life—the river. But to his utter dismay, he found that the river was dying; lamenting in agony, but the world refused to hear, it refused to see the river that was once the lifeblood, now drained of life.

He reached out and collected water into his palm. The water was black; he quickly threw it back, but the acid had already left a mark on his hands. The river was bubbling with chemicals and untreated industrial waste; plastic bottles floated on its surface. The developed cities of Lahore, Faisalabad, and Sheikhupura had disposed of all their urban and industrial waste into the Ravi, turning it into a cesspool of development. Owing to the pharmaceutical industries, the water was infused with paracetamol, nicotine, and concentrates of epilepsy and diabetes drugs.

This was the reason why the air surrounding the river hung with a deathly odour that reeked of chemicals, faeces, pesticides, and garbage. Madhu struggled to breathe in the air; he felt his innards churn with the smell of the river. He could only imagine the waterborne diseases it carried. There was a time when the river water was so clean that people would drink and bathe in it.

Now, even a mosquito wouldn’t want to come near it. Two hundred species of fish had gone extinct in the polluted river. Madhu looked around and realised that the river felt ashamed and, like a guilty culprit, hid beneath the bridge, hoping the earth would swallow it and leave no traces behind of its fall from grace.

The Ravi has an immense history rooted in local traditions, preserved in the form of folklore, poetry, and legends. The earliest human settlement flourished at the southern banks of the River Ravi in 3800 BC with the founding of Harappa

In its former glory, the river meandered at the heart of the city, which today is known as ‘Buddha Darya.’ Buddha Darya was far from old; it was full of vitality, vibrancy, and enriched by the annual floods that expanded its flow. In the monsoon season, the river would flood and spill over onto the floodplains, which came to life with the alluvial deposits. All the fields near the river were an array of lush green and yellow vibrancy. The river ran adjacent to the Shahi Qila, reaching the steps of Data Darbar and bidding the saints farewell as it curled around the walled city, providing it with a natural border for protection.

During Akbar’s reign, the river functioned as a trade highway where numerous boats and ships would carry grains, rice, spices, and silk from Lahore to Kandahar and Central Asia. The Khizri Gate (also known as Sheranwala Gate) was a dockyard where ships stopped and offloaded their cargo. Khizri Gate was named after Khawaja Khizr, who was believed by boatmen to rule the kingdom of the rivers.

There are many legends attached to Khawaja Khizr; some believe he was a saint, an angel, or something even greater. The enigmatic figure of Khawaja Khizr emulates the myriad mysteries wrapped in the river. Moreover, the Ravi Mela is celebrated in the monsoon season to commemorate Khawaja Khizr, Abdul Qadir Jilani, and Mai Bairian.

These personalities are revered by the community of fishermen, boatmen, and traders, who get together on the riverbank and observe certain rituals connected with the river. Young boys and girls make paper boats decorated with petals, candles, and grains and float them in the river. The big festival is celebrated with great enthusiasm as people dance to the music of the drums while holding out little boats offered as presents to the river.

Furthermore, the Ravi has an immense history rooted in local traditions, preserved in the form of folklore, poetry, and legends. The earliest human settlement flourished at the southern banks of the River Ravi in 3800 BC with the founding of Harappa. Moreover, in the Vedic period, the hymns of the Rig Veda were revealed to rishis who meditated and compiled the Vedas on the banks of the Ravi, which was then called Iravati.

According to the Rig Veda, the famous battle of the ten kings was fought on its banks, whereby King Bharata emerged victorious and defeated the other ten kings. Likewise, Guru Nanak founded the city of Kartarpur near the River Ravi. He built the first Sikh Gurdwara at Kartarpur and spent his life cultivating crops in the fertile lands of Punjab, teaching his disciples the tenets of Sikhism. The crops that he harvested on the riverbank were distributed among the poor in Langar, which celebrated the spirit of local humanism.

In short, the two great religions of South Asia—Hinduism and Sikhism—were founded on the banks of the River Ravi. Guru Nanak’s poetry is grounded in the culture, traditions, and landscape of Punjab. He famously stated, “Pavan Guru Pani Pita Mata Dharath Mahat,” whereby he meant that the air is guru, water is father, and earth is mother.

Madhu sadly looked at the river and whispered, “Pavan Guru Pani Pita Mata Dharat Mahat.” He held his breath as the smog hung in the air like a grim reaper. At that moment, a fiendish hand produced a plastic bottle from the black, sludgy water. He felt the earth beneath him shaking, and to his horror, he saw a skyscraper erect out of nowhere. Madhu could not tell whether he was standing on the shore or drowning underwater. The river had receded so much that he could not find himself in time and space, although he desperately clung to the remains of the dying river.