The raid to get Osama bin Laden was one of the most dramatic events in recent world history. The founder of the first truly global non-state terror group Al Qaeda (AQ), Osama bin Laden - known more commonly by his initials OBL - was the most wanted man in the world at one point in time. Scion of a wealthy Saudi family, bin Laden was a veteran of the Soviet war in Afghanistan, having fought on the mujahideen side. He rose to global prominence in September 2001, when his operatives carried out the 9/11 attacks, hijacking passenger planes and crashing them into the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon.

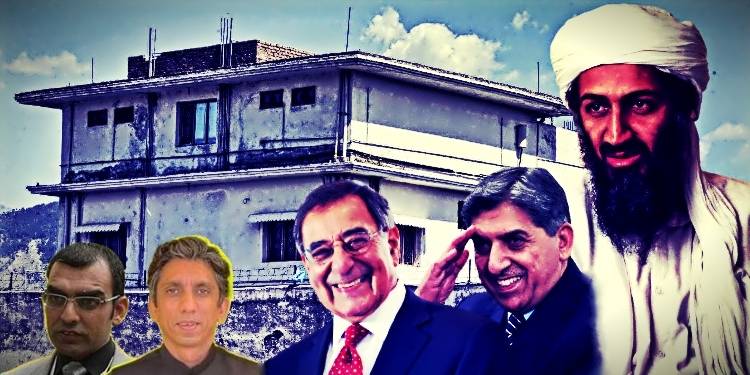

That horrific incident redefined the world as we knew it, unleashing a chain of events that still presents humanity today as interlocked in a 'clash of civilizations' along religious identity. Hunted for a decade in Afghanistan and around the world, Osama bin Laden was finally killed by US special forces in Abbottabad, Pakistan, on May 1-2, 2011: the late hours of May 1 in the US, and the early hours of May 2 in Pakistan. Sources say that the mission - first called Operation Geronimo, then Operation Neptune Spear, to avoid offending Native American sentiments - started at 1am Pakistan time, but movies like 'Zero Dark Thirty', and books published by US military warfighters who claim to have been part of the operation, leave little else to the imagination.

While many believe that Osama bin Laden has become an infamous figure now buried in the annals of history, his death and its aftermath still loom large over Pakistan, its state, and its Muslim majority populace even today.

"The crux of the story is that Osama bin Laden was located on Pakistani soil, and this was not a positive omen for Pakistan at all," senior journalist Azaz Syed says in his latest TalkShock vlog, where he discusses excerpts from his book 'The Secrets of Pakistan's War on Al Qaeda'.

The operation to neutralise OBL 'exposed' Pakistan's perfidious policy of supporting extremism and 'like-minded' militant groups while simultaneously claiming 'front-line' status as an American ally in its war on terror. The Osama bin Laden raid marked the beginning of a visible erosion in Pakistan's credibility and trustworthiness as a responsible member of the international community, and thereafter, India's allegations of Pakistan being the 'epicentre of terror' began attaining credence in the West.

Even before May 2011, there were evident signs of mutual suspicion between the US and Pakistan. Azaz Syed says that in a visit to the US, then-PM Yousaf Raza Gillani was informed by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that US intelligence knew OBL was hiding in Pakistan. "Even then, American intelligence was not willing to trust Pakistan," Azaz Syed says, and adds that, "they (US) complained that whenever we inform Pakistan about a high value target, the target suddenly disappears or escapes". These instances obviously made the US cease sharing vital intelligence with their Pakistani counterparts.

Azaz Syed also remembers that then-CIA director Leon Panetta said that Pakistan was either an accomplice in harbouring bin Laden, or incompetent to not detect him under their nose. But Azaz also states that then-ISI chief Lt Gen (retd) Pasha spoke on the phone with Panetta the night of the Osama bin Laden raid, and congratulated his US counterparts on a successful operation.

Eventually, the Pakistani state chose to be perceived as incompetent, and in fact, engaged in whataboutery: the mainstream narrative peddled by Pakistan at the time was if the ISI was incompetent to not have found Osama bin Laden for so many years, then the CIA was also incompetent because they could not prevent the 9/11 attacks by Al Qaeda. "It was an intelligence double-failure," Azaz Syed says, adding "if they didn't know he was there, that's bad, but if they knew he was there and did nothing, that's even worse".

TalkShock co-host and senior investigative journalist Umar Cheema shares an anecdote that he was in the US during May 2011 giving lectures at universities, and felt very hopeful about Pakistan. But a few days before his planned return, at a dinner in New York, the story of the Osama bin Laden raid broke. "It not only caused me a lot of embarrassment, but also destroyed all the hope and positivity I had been feeling about returning to Pakistan," Cheema says.

The killing of bin Laden on Pakistani soil, some kilometres away from the Pakistan military academy (PMA) at Kakul, also damaged the reputation of Pakistan's powerful army. The people of Pakistan started questioning how foreign military forces could penetrate so deep into Pakistani territory, conduct an operation and retreat safely, when Pakistan had the world's 'number one' army.

Moreover, the international community now had the perfect reason to at least be hesitant in trusting the Pakistani military and intelligence institutions for serious counterterrorism operations. It was not just OBL's death, but his presence in Pakistan for years, which raised serious questions that have yet to receive plausible answers even today.

After the Osama bin Laden raid, civil-military relations in Pakistan also turned sour, and a memo came to public knowledge which allegedly revealed plans by the then-PPP government to seek American diplomatic and military assistance against a potential coup by the-then miltablishment, led by Gen (retd) Musharraf's successor Gen (retd) Ashfaq Kayani, and then-DG ISI Lt Gen (retd) Ahmad Shuja Pasha. That memo was apparently addressed to then-US chairman joint chiefs, Admiral (retd) Mike Mullen, who had called the Taliban's Haqqani network - which now controls the Afghan interior ministry and intelligence service - a veritable arm of the ISI.

But at that time, the Pakistani establishment's links with the enemies of the 'global war on terror' - groups like Al Qaeda, and insurgent militias like the Taliban - were downplayed and contextualised (or whitewashed) as remnants or unauthorised holdovers from the Afghan jihad era. Pakistan conducted military operations in its tribal regions bordering Afghanistan, and the Musharraf regime apprehended many suspected terrorists and handed them over to the US. Meanwhile, as it turns out, it is becoming more likely that elements affiliated with Pakistani intelligence could have known that Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden was being housed in Abbottabad - but Azaz Syed is at pains to clarify that this could be at a personal level, and is alleged but has yet to be confirmed at the institutional or policy levels.

According to Azaz Syed, construction of the Abbottabad compound that housed Osama bin Laden started sometime in 2004, and was completed by sometime in 2005, after which the Al Qaeda (AQ) leader came to live there. Attacks by AQ and its affiliated Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP) against Pakistani targets declined in frequency from 2005-06 onwards, according to Azaz Syed. This corresponds to the time that OBL settled in Abbottabad, as well as the rise of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). TTP founder Baitullah Mehsud was a fan of Osama bin Laden fan, according to Azaz Syed, who says that bin Laden also wrote letters to Mehsud.

Osama bin Laden only left his Abbottabad compound thrice between 2005 and his death in 2011, according to new revelations by Azaz Syed.

One of those times was to visit the tribal areas, according to Azaz Syed, in reference to the tribal districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Azaz says that in 2005, after setting up in the Abbottabad compound, Osama bin Laden made his first trip out to meet someone that Azaz does not identify. Azaz says that the person was informed by a Pakistani intelligence official that he should prepare for an important guest, and the guest turned out to be OBL. "The rest is history," Azaz concludes without elaborating further.

Another one of those times was in 2006 to go to Haripur to meet Ilyas Kashmiri, a militant commander who led the Kashmir-focused militant group HuJI at one time, and later became Al Qaeda's central military commander. Kashmiri was reported to operate militant training camps in Razmak, North Waziristan, where he would prepare terrorists and then dispatch them to carry out attacks in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Azaz Syed reveals that in their 2006 meeting, Kashmiri told OBL about the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) terror group planning the Mumbai attacks, which eventually occurred in November 2008, and offered that he could "hijack" their operation and mold it towards their goals; focusing on American and Jewish targets in Mumbai. Azaz purports that one of the cells that infiltrated Mumbai and attacked a Jewish outreach centre, Nariman House, was actually affiliated more with AQ than LeT.

Azaz Syed concedes that at that time (2000s) there were many in the Pakistan military rank-and-file who sympathized with bin Laden and his agenda, but that still does not equate with institutional support for him or his proscribed outfit. "There are footprints of individuals, but time will tell whether these were just individuals or whether they were following policy decisions," Azaz says.

Abbottabad residents living close to the OBL compound told Azaz Syed that they could never have believed that such a high profile terror leader was living there. "To this day, they still don't believe it, they say it is an American conspiracy," Azaz says.

Azaz Syed also recalls that a few days before the Osama bin Laden raid, then-army chief Gen (retd) Kayani visited PMA Kakul, and an intelligence sweep of the area was done, which still did not reveal the presence of the Al Qaeda supremo. Azaz also reveals that the local sector office of the military intelligence (MI) was close to the OBL compound, but instead of being reprimanded, officers posted there were transferred to other stations. In fact, Azaz says, the entire blame was shoveled on the local police for not knowing that the world's most wanted terrorist was in their jurisdiction. "But it was not in the SHO's domain," Azaz says as he refers to the local police station incharge.

"The heads of the top level officials that were supposed to roll, that never happened. Nobody was given a proper punishment," Azaz laments. He adds that the May 2, 2011 operation is considered akin to "the 1971 surrender, because American forces infiltrated Pakistani territory, came in and picked up whoever they wanted to pick up, and we could do nothing but watch".

"There are even questions whether the Pakistan air force's radars were working or not," Azaz says, at which his co-host Umar Cheema quipped, "maybe they were only working 8 hours a day, during office hours".

Cheema also laments that the report of the Abbottabad Commission, formed to investigate the incident and headed by former Supreme Court Judge and former NAB chairman Javed Iqbal, has still not been made public despite 12 years having passed. "The lesson for us is that Pakistan is not willing to learn any lessons," Cheema states.

That horrific incident redefined the world as we knew it, unleashing a chain of events that still presents humanity today as interlocked in a 'clash of civilizations' along religious identity. Hunted for a decade in Afghanistan and around the world, Osama bin Laden was finally killed by US special forces in Abbottabad, Pakistan, on May 1-2, 2011: the late hours of May 1 in the US, and the early hours of May 2 in Pakistan. Sources say that the mission - first called Operation Geronimo, then Operation Neptune Spear, to avoid offending Native American sentiments - started at 1am Pakistan time, but movies like 'Zero Dark Thirty', and books published by US military warfighters who claim to have been part of the operation, leave little else to the imagination.

While many believe that Osama bin Laden has become an infamous figure now buried in the annals of history, his death and its aftermath still loom large over Pakistan, its state, and its Muslim majority populace even today.

"The crux of the story is that Osama bin Laden was located on Pakistani soil, and this was not a positive omen for Pakistan at all," senior journalist Azaz Syed says in his latest TalkShock vlog, where he discusses excerpts from his book 'The Secrets of Pakistan's War on Al Qaeda'.

The operation to neutralise OBL 'exposed' Pakistan's perfidious policy of supporting extremism and 'like-minded' militant groups while simultaneously claiming 'front-line' status as an American ally in its war on terror. The Osama bin Laden raid marked the beginning of a visible erosion in Pakistan's credibility and trustworthiness as a responsible member of the international community, and thereafter, India's allegations of Pakistan being the 'epicentre of terror' began attaining credence in the West.

Even before May 2011, there were evident signs of mutual suspicion between the US and Pakistan. Azaz Syed says that in a visit to the US, then-PM Yousaf Raza Gillani was informed by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton that US intelligence knew OBL was hiding in Pakistan. "Even then, American intelligence was not willing to trust Pakistan," Azaz Syed says, and adds that, "they (US) complained that whenever we inform Pakistan about a high value target, the target suddenly disappears or escapes". These instances obviously made the US cease sharing vital intelligence with their Pakistani counterparts.

Azaz Syed also remembers that then-CIA director Leon Panetta said that Pakistan was either an accomplice in harbouring bin Laden, or incompetent to not detect him under their nose. But Azaz also states that then-ISI chief Lt Gen (retd) Pasha spoke on the phone with Panetta the night of the Osama bin Laden raid, and congratulated his US counterparts on a successful operation.

Eventually, the Pakistani state chose to be perceived as incompetent, and in fact, engaged in whataboutery: the mainstream narrative peddled by Pakistan at the time was if the ISI was incompetent to not have found Osama bin Laden for so many years, then the CIA was also incompetent because they could not prevent the 9/11 attacks by Al Qaeda. "It was an intelligence double-failure," Azaz Syed says, adding "if they didn't know he was there, that's bad, but if they knew he was there and did nothing, that's even worse".

TalkShock co-host and senior investigative journalist Umar Cheema shares an anecdote that he was in the US during May 2011 giving lectures at universities, and felt very hopeful about Pakistan. But a few days before his planned return, at a dinner in New York, the story of the Osama bin Laden raid broke. "It not only caused me a lot of embarrassment, but also destroyed all the hope and positivity I had been feeling about returning to Pakistan," Cheema says.

The killing of bin Laden on Pakistani soil, some kilometres away from the Pakistan military academy (PMA) at Kakul, also damaged the reputation of Pakistan's powerful army. The people of Pakistan started questioning how foreign military forces could penetrate so deep into Pakistani territory, conduct an operation and retreat safely, when Pakistan had the world's 'number one' army.

Moreover, the international community now had the perfect reason to at least be hesitant in trusting the Pakistani military and intelligence institutions for serious counterterrorism operations. It was not just OBL's death, but his presence in Pakistan for years, which raised serious questions that have yet to receive plausible answers even today.

After the Osama bin Laden raid, civil-military relations in Pakistan also turned sour, and a memo came to public knowledge which allegedly revealed plans by the then-PPP government to seek American diplomatic and military assistance against a potential coup by the-then miltablishment, led by Gen (retd) Musharraf's successor Gen (retd) Ashfaq Kayani, and then-DG ISI Lt Gen (retd) Ahmad Shuja Pasha. That memo was apparently addressed to then-US chairman joint chiefs, Admiral (retd) Mike Mullen, who had called the Taliban's Haqqani network - which now controls the Afghan interior ministry and intelligence service - a veritable arm of the ISI.

But at that time, the Pakistani establishment's links with the enemies of the 'global war on terror' - groups like Al Qaeda, and insurgent militias like the Taliban - were downplayed and contextualised (or whitewashed) as remnants or unauthorised holdovers from the Afghan jihad era. Pakistan conducted military operations in its tribal regions bordering Afghanistan, and the Musharraf regime apprehended many suspected terrorists and handed them over to the US. Meanwhile, as it turns out, it is becoming more likely that elements affiliated with Pakistani intelligence could have known that Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden was being housed in Abbottabad - but Azaz Syed is at pains to clarify that this could be at a personal level, and is alleged but has yet to be confirmed at the institutional or policy levels.

According to Azaz Syed, construction of the Abbottabad compound that housed Osama bin Laden started sometime in 2004, and was completed by sometime in 2005, after which the Al Qaeda (AQ) leader came to live there. Attacks by AQ and its affiliated Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP) against Pakistani targets declined in frequency from 2005-06 onwards, according to Azaz Syed. This corresponds to the time that OBL settled in Abbottabad, as well as the rise of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). TTP founder Baitullah Mehsud was a fan of Osama bin Laden fan, according to Azaz Syed, who says that bin Laden also wrote letters to Mehsud.

Osama bin Laden only left his Abbottabad compound thrice between 2005 and his death in 2011, according to new revelations by Azaz Syed.

One of those times was to visit the tribal areas, according to Azaz Syed, in reference to the tribal districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Azaz says that in 2005, after setting up in the Abbottabad compound, Osama bin Laden made his first trip out to meet someone that Azaz does not identify. Azaz says that the person was informed by a Pakistani intelligence official that he should prepare for an important guest, and the guest turned out to be OBL. "The rest is history," Azaz concludes without elaborating further.

Another one of those times was in 2006 to go to Haripur to meet Ilyas Kashmiri, a militant commander who led the Kashmir-focused militant group HuJI at one time, and later became Al Qaeda's central military commander. Kashmiri was reported to operate militant training camps in Razmak, North Waziristan, where he would prepare terrorists and then dispatch them to carry out attacks in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Azaz Syed reveals that in their 2006 meeting, Kashmiri told OBL about the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) terror group planning the Mumbai attacks, which eventually occurred in November 2008, and offered that he could "hijack" their operation and mold it towards their goals; focusing on American and Jewish targets in Mumbai. Azaz purports that one of the cells that infiltrated Mumbai and attacked a Jewish outreach centre, Nariman House, was actually affiliated more with AQ than LeT.

Azaz Syed concedes that at that time (2000s) there were many in the Pakistan military rank-and-file who sympathized with bin Laden and his agenda, but that still does not equate with institutional support for him or his proscribed outfit. "There are footprints of individuals, but time will tell whether these were just individuals or whether they were following policy decisions," Azaz says.

Abbottabad residents living close to the OBL compound told Azaz Syed that they could never have believed that such a high profile terror leader was living there. "To this day, they still don't believe it, they say it is an American conspiracy," Azaz says.

Azaz Syed also recalls that a few days before the Osama bin Laden raid, then-army chief Gen (retd) Kayani visited PMA Kakul, and an intelligence sweep of the area was done, which still did not reveal the presence of the Al Qaeda supremo. Azaz also reveals that the local sector office of the military intelligence (MI) was close to the OBL compound, but instead of being reprimanded, officers posted there were transferred to other stations. In fact, Azaz says, the entire blame was shoveled on the local police for not knowing that the world's most wanted terrorist was in their jurisdiction. "But it was not in the SHO's domain," Azaz says as he refers to the local police station incharge.

"The heads of the top level officials that were supposed to roll, that never happened. Nobody was given a proper punishment," Azaz laments. He adds that the May 2, 2011 operation is considered akin to "the 1971 surrender, because American forces infiltrated Pakistani territory, came in and picked up whoever they wanted to pick up, and we could do nothing but watch".

"There are even questions whether the Pakistan air force's radars were working or not," Azaz says, at which his co-host Umar Cheema quipped, "maybe they were only working 8 hours a day, during office hours".

Cheema also laments that the report of the Abbottabad Commission, formed to investigate the incident and headed by former Supreme Court Judge and former NAB chairman Javed Iqbal, has still not been made public despite 12 years having passed. "The lesson for us is that Pakistan is not willing to learn any lessons," Cheema states.