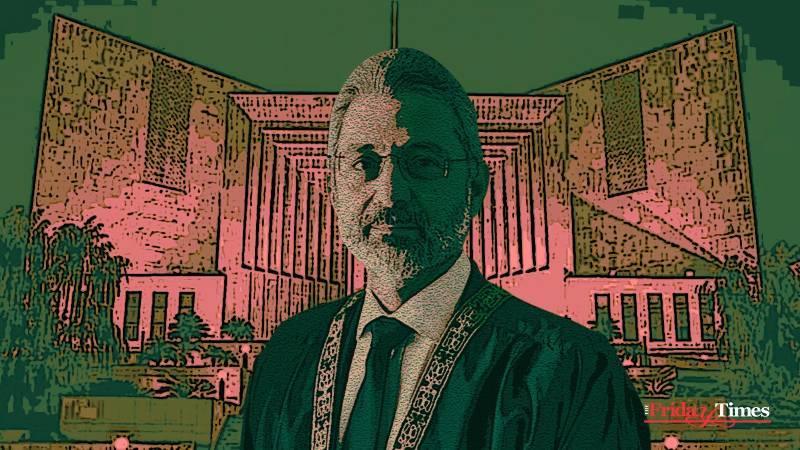

Beyond the prevailing arguments for or against former chief justice Faez Isa, this column is to offer a distinct perspective on his legacy, shaped by both his tenure as Chief Justice and the period leading up to it.

The peak of Justice Isa's legacy was marked by a highly controversial court ruling on the allocation of the reserved seats. In this case, eight out of thirteen judges ruled contrary to the remaining five, a split that both pleased and displeased various political and religious factions. The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), the primary beneficiary of the ruling, celebrated it with fervour, for obvious reasons.

In stark contrast, the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) expressed outrage, as the decision posed a major setback for the party if implemented. Immediately following the court's announcement, the PML-N held a press briefing, pointing out gaps in the verdict that they argued would set a troubling precedent: issuing a judgment that benefited a political party not directly involved in the appeal. The PML-N perceived this as an attempt by the judiciary to reshape the country’s Constitution.

Beyond the immediate controversy, the decision exposed unprecedented polarisation within the judiciary, crossing boundaries not seen before. Beyond its legal implications, the verdict reflected a profound ideological divide in society, with one view holding a significant majority. Interestingly, this divide is not a simple right-versus-left conflict; rather, it exists within right-leaning factions themselves. Each side claims to uphold the supremacy of parliament and the rule of law but interprets these principles according to differing frameworks and priorities.

While the Tamizuddin Khan case marked the first significant judicial split on a critical national issue, the case of the reserved seat represents a second divide of comparable magnitude

If implemented, the verdict would unseat the current government and restore the PTI to power, echoing previous instances of judicial intervention that have shadowed the Parliament since the landmark 1954 ruling against the Constituent Assembly, known as the Maulvi Tamizuddin Khan case. Initially, a two-judge bench of the Sindh High Court had ruled in favor of the Assembly, but a five-judge Supreme Court bench later overturned this decision unanimously on appeal. The judiciary introduced the "Doctrine of Necessity" to justify its ruling, a term that has since influenced similar decisions.

This decision ignited an ideological rift within ruling circles over the question of supremacy: should ultimate authority lie with the executive or with parliament? The years that followed saw coup after coup, culminating in 1958 with the rise of an unchallenged military ruler, Ayub Khan, just four years after the initial intervention in 1954. Since then, Pakistan has witnessed the removal of three prime ministers— Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Yousuf Raza Gilani, and Nawaz Sharif — each through a judiciary that played as pivotal a role as military leaders of the past.

While the Tamizuddin Khan case marked the first significant judicial split on a critical national issue, the case of the reserved seat represents a second divide of comparable magnitude. In the Tamizuddin case, most of the judiciary aligned with the establishment; in this latest case, however, it is a political party— specifically PTI —that fully supports the judges who issued a favourable ruling. Meanwhile, the establishment, claiming neutrality, appears to play a role that ultimately supports the ruling party and the dissenting judges.

One of the most troubling aspects of this political landscape is the targeting of former Chief Justice Faez Isa, who, along with four other judges, dissented from the majority verdict, calling it an attempt to alter the Constitution. Regardless of ideological stance, both the eight judges who issued the ruling and the five dissenters, including Justice Isa, deserve equal respect. Dissenting judgments are a normal part of court proceedings, open to review, analysis, and criticism within the bounds of freedom of speech and decorum.

Former Chief Justice Isa made deliberate efforts to shift that balance in favour of parliamentary supremacy, a move that many within the judiciary view as a threat to the institution’s integrity

Unfortunately, boundaries of civility were breached even while outgoing CJP Isa remained in office. This reached an unsettling level in England recently, where PTI protesters, led by Shayan Ali, surrounded and banged on former CJP Isa’s car to express opposition to his decisions, particularly those that conflicted with PTI’s interests. Later, in a media statement, Shayan Ali asserted: "I don't condone any act of violence by anyone. The HRA is clear in the rights it gives for peaceful protest and legal opposition. The right to assembly and the right to protest are enshrined in the UK legal system."

This situation marks a concerning shift in the country’s political landscape. Two prime ministers, Nawaz Sharif and Yousuf Raza Gilani were removed in the past decade through unanimous court verdicts delivered by five-judge and three-judge benches, respectively. In both cases, there was no backlash—no trolling, defamation, or public disorder. Even the judiciary and legal community remained silent, reinforcing the judiciary’s authority over executive powers.

However, former Chief Justice Isa has made deliberate efforts to shift that balance in favour of parliamentary supremacy, a move that many within the judiciary view as a threat to the institution’s integrity. The reserved seat case presented yet another opportunity for the judiciary to undo those efforts. PTI, historically critical of former CJP Isa, unexpectedly became a beneficiary of this judicial shift, without acknowledging a key point: if CJP Isa had, like his predecessors, appointed a three-judge bench for the reserved seats case, would the PTI have received the same favourable outcome they enjoyed under his new approach?

The behaviour adopted by the PTI supporters in London casts a poor light on those who supported the majority verdict. If this trend continues, it risks normalising a pattern where disputes are resolved through intimidation, force, and unruly mobs. Defending violence as a form of free expression reflects a troubling trajectory within the PTI faction, one that leans toward coercive majoritarian rule—where inclusivity and freedom are dictated solely by the majority. Under such a system, would judges and political opponents truly be able to operate independently?

Both sides of this divide must now consider what they envision for the country: a genuinely inclusive democratic system or an exclusive majoritarian rule. The choices are clear, but the decision rests with those actively shaping this political landscape.