“The act of painting is a means to confront, control and combat the acts of violence in our surroundings.”

This is the artist’s statement accompanying the latest show of Quddus Mirza’s work that opened on September 7 2021. Entitled “Once Upon Many Times,” this is the seventh solo show of Quddus’s work at Canvas Gallery in Karachi (he has also been part of a couple of earlier group shows at Canvas). The works are from 2021, with one exception from late last year. These are some of Quddus’s most political works and are a reflection not just of the random and overt acts of violence in his world and surroundings, but also evoke the psychic violence and toll resulting from the pandemic and the dread that the world has been living in for over a year and a half.

Rooted in his take on abstract expressionism, Quddus has embraced and appropriated the art form, making it his very own. He has given it a unique and distinctive flavour that propels it firmly into today’s (and his own) world by placing it in the specific context of his surroundings. A respected artist, art critic, art teacher and curator, he has been producing work for almost four decades. Quddus has had a distinguished career as an artist. After his art schooling in Lahore, he trained at the Royal Academy of Art in London, where he was the first Pakistani art student admitted to the prestigious Painting program. While completing his M.A., Quddus won the MacLellan Prize for painting. Over the years he has won several awards and distinctions. He has exhibited continually over the years, both in Pakistan and internationally. He has had sixteen solo shows in Pakistan and the UK and been a part of numerous group shows across the globe. His work is in the collections of the British Museum, the Royal College of Art, the Islamabad National Gallery and in numerous private collections around the world.

Abstract expressionism is not everyone’s cup of tea. It requires the viewer to cast aside preconceived notions of what constitutes art and demands patience and prolonged interaction between the viewer and the work

His first solo exhibition was after graduating with honours and distinction from the National College of Art, Lahore, but he was producing work even as a student. Although his early work experimented with various styles (as all students do) covering still life, landscapes, figurative and other forms, he was already experimenting with abstraction, and using mixed media and collage.

I came across his work a few years back and was immediately struck by the powerful images. Quddus was using expressionism in a way that was exciting and challenging. He seemed to be provoking me the viewer, and proudly proclaiming that his art was not for the fainthearted. You may be seeing pretty colors and strange images, but look closely and you will understand what is intriguing you. I was familiar with abstract expressionism as used by international, mainly American, artists but had not seen much expressionist work by any modern Pakistani artist.

Representational abstraction had been the hallmark of a number of earlier Pakistani artists, but over the years had declined in relative importance. The preference among most younger artists and art students was for newer, and redeveloped styles: miniature painting, figurative works, variations on cubism and pop art and some others. Quddus’s work was boldly using abstract expressionism. This struck me as radical and unorthodox. Abstract expressionism had shaken the art world and had been a shout out against the destruction that had roiled the Western world just before during and after the Second World War. But it had not gained much prominence in Pakistan.

While its roots lay in earlier twentieth century artists, in particular Arshile Gorky, but also Hans Hoffman and even earlier in the work of Wassily Kandinsky, it is recognized today as a post second world war phenomenon, beginning in the late 1940s and early 1950s. It also became the first and foremost art movement developed in the US, securing the position of New York as the new center of the art world, a position that had been held earlier by Paris. Like all art movements, it drew upon earlier forms, not least from pre-war German abstraction, Cubism, Dadaism, and others, including Surrealism.

The term abstract expressionism had been used in Germany as early as 1919, but as a movement and a distinct style it wasn’t until the so-called ‘action’ paintings of Jackson Pollock, William de Kooning and Franz Kline, the ‘white writing and near calligraphic’ canvases of Mark Tobey, and Robert Motherwell, the ‘color field’ paintings of Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman and the work of several others that the term came to be associated with a distinct movement. There were other early proponents of the style, including among others (in no particular order of importance) Lee Krasner, Clyfford Still, and Elaine de Kooning. Soon after, the pioneers were followed by Cy Twombly, Philip Guston, Helen Frankenthaler, Adolph Gottlieb and Agnes Martin and several others. Many of the later adherents moved away from action painting to variations on the colour field form. And other artists like Rauschenberg, in particular, were using multi-media with distinct influences of Surrealism.

These are the darkest works that Quddus has produced. Not dark in their colours, which, as always, are deceptively joyous and mostly bright. And they are painted onto the canvas in bold, exuberant style. It is the message embedded in the images

This was a movement that was characterized not by the similarity of each artist’s work to the other but by its rebelliousness, seeming spontaneity, visually anarchic style, idiosyncrasy and, to many critics, its nihilism. Abstract expressionism was a departure from representational abstraction, in particular as characterized by Cubism, and Dadaism, and a move towards pure abstraction. The primary focus became the expression of emotions and attitudes, using nonrepresentational means. Eliciting a visceral response became the primary purpose of the form, requiring prolonged interaction between the viewer and the art. Surrealism earlier had relied heavily on psychological underpinnings. Abstract expressionism went further and reflected the emotional mindset of the artists, eschewing representation and focusing instead on visual abstraction.

Seemingly apolitical, the movement was a response to the death and destruction, and nihilism of the second world war but also became a way to circumvent the stifling atmosphere and censorship of the post-war McCarthy era in the US. By relying on pure abstraction, it allowed for the politics of nihilism and rebellion to be ignored by the establishment. Later this was no longer a concern so artists such as Rauschenberg and Guston felt it was not necessary to avoid political messages. Abstract expressionism fell out of favor for a while, especially during the latter decades of the century but it never quite went away. Minimalism, pop art and several later forms drew heavily on it and the movement continued to inspire several generations of artists.

And this brings us to present day abstract expressionism. Recent turmoil around the globe has inspired many artists from various parts of the world to use similar forms or variations on it to give it new meaning and life. Whether it is a response to the world around them or an overt or subliminal reaction to personal and social trauma (not unlike and in many cases worse than that faced by post-war Europe) artists are continuing to use expressionism as a potent art form. In the case of Quddus Mirza, he has been using and developing this style for many years - and is perhaps the most prominent Pakistani artist of his generation, using it to great effect.

I see various influences and the transition that has occurred in Quddus’s work. The landscapes are reminiscent of the early impressionists, Pissarro, Monet (‘Water Lilies’ is a direct homage) and others

Using expressionism to express his take on his world in seemingly pure abstraction, doodles and mixed media collage, his work has become increasingly topical and political with inspiration drawn from various forms of the movement, from color field to Twombly style doodles to Rauschenberg inspired multi-media, to variations of pop art. As I delved deeper into his body of work I found that Quddus had since very early in his artistic practice been experimenting with various styles of expressionism and over the years has developed something unique, distinctive and inimitable.

Abstract expressionism is not everyone’s cup of tea. It requires the viewer to cast aside preconceived notions of what constitutes art and demands patience and prolonged interaction between the viewer and the work. Looking at the work may evoke indifference at first but it soon begins to produce feelings and emotions, a response that is unique to the viewer. Feelings that are impossible to describe in words alone. Sheer delight and joy, introspection, remembrance, anger, and even depression are some of the emotions that have been experienced and reported. Absurdity and nihilism may lie at the heart of the work but ultimately it becomes life affirming and a way to understand and overcome the travails of the world around the artist and us, the viewer.

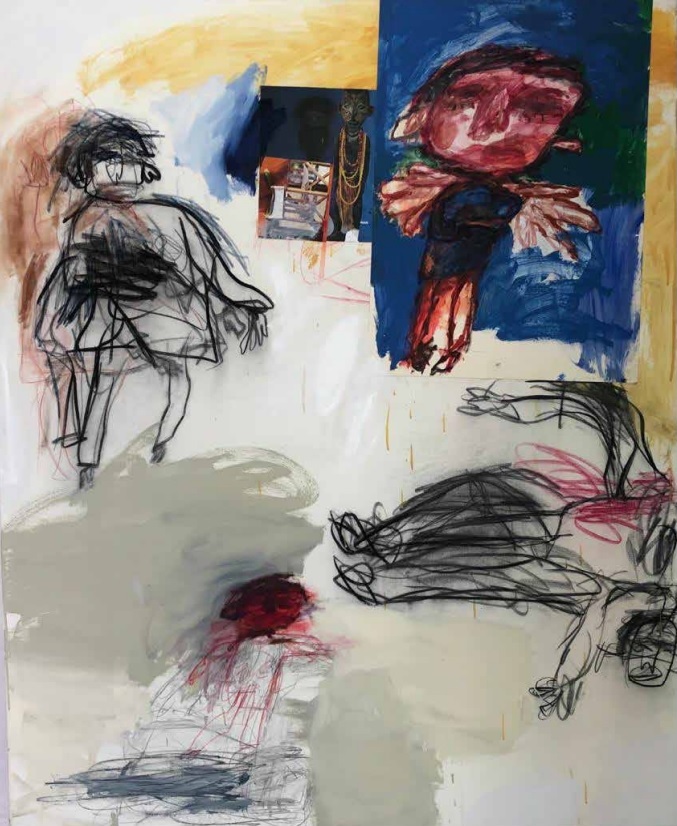

Unlike many practitioners of the form Quddus prefers to give titles to each work; titles that are seemingly simple but appear to reflect, to my mind, double meaning and a resounding challenge to the establishment. ‘Anatomy Lessons’ (2021) is a vision of the effect of violence in our society on the physical and mental state of people. Disembodied body parts, heads, hands and feet are carelessly doodled around flat color fields, with a large seemingly dead body lying at the bottom right. A map of Pakistan at the top right is pasted on the canvas with clearly marked explosions scattered across all sections of the map. As these images become apparent, the beauty of the colors is shattered, not unlike an explosion. A lesson in what violence can do to the anatomy.

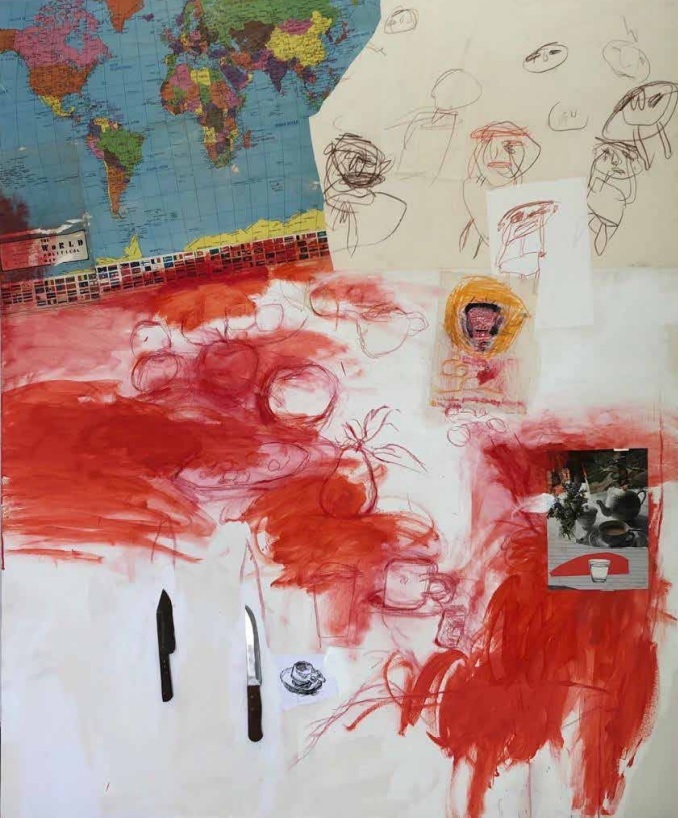

‘Still Life’ (2021) again uses a play on

words. Quddus places maps and other objects attached to the canvas to great effect. Here again a map is pasted, this time on the top left side; a map of the world. Why not go universal he seems to be saying. Small objects are drawn much as in a still life, cups, saucers, a teapot, and a plate of fruit but some of the objects are incongruous, a lone piece of fruit is thrown in among traumatized children and adults, and an actual knife, alongside its painted image added to the mix of what could be rockets, or drones. The predominant use of the color red, conveys the violence that has been wreaked on the world using both advanced and ordinary weapons. Has life been stilled by endless wars and continuing violence across the globe? Or perhaps the message is that even after all the destruction life still remains.

‘Landscape’ from the same show is a deceptively simple work. A sheet of paper pasted onto the upper middle section of the canvas evokes a desert or a barren mountain. The colors here are more varied ranging from bright red, yellow and blue to much darker shades of green, brown and black. A couple of bodies are vaguely visible, one a seemingly dead person, the other a mangled and distorted horse. A few cars are also visible. But catching the eye most prominently are two separate images. The first are the words RAIN with a bright blue cloud above it; and the other are several graves in varying sizes with gravestones. Adding to the mystery is a lightly drawn figure lying prone on what may be a double bed. A death bed or a place of rest? And rain may fall but even nature cannot wash away the blood that has been spilled.

The other three works in the show are in a similar vein. The ‘Obedient Angel’, a figure with flapping arms or perhaps wings, is following the instructions of a mysterious figure wielding a hammer like weapon. Is this an angel of death, with the body of a dead person and a bloodied child the victims of the perpetrator or puppet master? ‘Cityscape’ is divided into two distinct quadrants. The right showing rooftops and city squares with a large upside down female cadaver, showing anatomical details of the innards. The spinal column looking deceptively like a reptile, perhaps a crocodile, straddling the back of the dead woman. The left shows a very large cat like creature lying dead at the base, and above it an interior of a room with a window and a person in the room. ‘Black Crow” is also in two sections. Here is another symbol of death and below the eponymous bird is a large figure with the words ‘chair’ written below. A place of rest or execution? On the right is another large, clearly mangled and distorted figure taking up most of the space. The color palette in all the work is both deceptively bright, coupled with ominously dark colors, with red being the most prominent.

These are the darkest works that Quddus has produced. Not dark in their colours, which, as always, are deceptively joyous and mostly bright. And they are painted onto the canvas in bold, exuberant style. It is the message embedded in the images. At his previous show just a little over two and a half years earlier, the work - while still dealing with death as one of the themes - was combined with love as the antithesis. This time it is death and desolation, brought about by violence that is the sole theme. It is as if the artist was struggling in his own mind to come to terms with the futility of existence, a sign of the present times, and further resulting from the health crisis that the world has been facing for well over a year and a half. All boundaries or antidotes to violence appear to have disappeared.

In 2019, loneliness was the subject of ‘How to be Alone’, and unrequited love in ‘It Must’. Death featured prominently in ‘B 4 Blood’ but here it was referenced through the twin towers being struck by an airplane and animals seemingly slaughtered. In ‘Death and the Maiden’ there was again an airplane but this time accompanied by a military map charting sites being attacked. Alongside that is a lone female figure being subjected to violence by an ominous looking man, portraying perhaps a crime of passion, the negation of love. ‘In Between the Two’ was portraying either a choice between two loves, or between love and death. The bleakest of the works ‘A Brief History of Our Time’ portrayed a lone figure staring into darkness and the abyss.

Going through images of his work from his entire art practice, I see various influences and the transition that has occurred in Quddus’s work. The landscapes are reminiscent of the early impressionists, Pissarro, Monet (‘Water Lilies’ is a direct homage) and others. The still life works are channeling Cezanne, and Gauguin with bold, almost flat colors. Portraits are reminiscent of Van Gogh and early Picasso. Later the work becomes more playful, and humorous, drawing upon Rauschenberg, and Twombly, and various pop artists. Soon collages, mixed media and some silk screen prints start to appear. Explicit writing, doodles and maps are used more frequently.

Soon abstraction and expressionist abstraction becomes the dominant style. However, the playfulness and humor in the works remains. Colors become flatter and brighter, interspersed with dark areas. It was only in the early part of this century that seriousness and darkness begin to take center stage, and that is where the artist finds himself today. It signals a maturity in the work, but also a more considered response to his surroundings. Is Quddus saying that he feels there is less to laugh about? He appears to be struggling and trying to come to terms with this through art. The apparent turmoil in his mind has become the centerpiece of his practice. I, for one, cannot wait to see where his art will go next.