Pakistan's economic situation is currently in a state of flux. Inflation has been on the rise and economic growth has been sluggish. The devaluation of the Pakistani Rupee has put further strain on the economy, making it difficult for individuals and businesses to cope with rising costs.

As per recent figures, released by the statistics bureau, inflation for January was recorded at 27.55 percent, highest since 1975. Further, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) reserves have also plunged to $3.09 billion, only sufficient to cover 20 days of imports.

Due to the bulk adjustment in currency and the subsequent fuel price hikes, experts are anticipating the inflation figures to breach the 30 percent barrier. This key drivers for the new wave of inflation would be commodities like fuel, edible oil and items for which Pakistan is a net importer.

In a recent report, the World Bank lowered Pakistan’s GDP growth forecast for 2023 to 2 percent, almost half of its earlier estimate.

Therefore, all eyes are on the Pakistan-IMF talks as the government is hopeful that the global financial institution will green light the $1 billion tranche and pave the way for other multilateral/bilateral funding.

Amidst all the chaos, experts have been pointing to the fact that this might be the worst economic crisis that the country has faced in the past 50 years. Therefore, it is worthwhile to explore that what transpired in the 1970s that many believe it to be a dark chapter in Pakistan’s economic history.

Situation in 1970s

The era was marked with political turmoil and the devastation caused by a war that broke the country in to two pieces.

The decade started with a conflict that resulted in a major hit on foreign currency reserves which plummeted to $160 million in January 1971, and Pakistan was unable to fulfil its obligation to commercial creditors.

“Arguably, the seeds for the (economic) slowdown were sown in the 1970s with the disruptions resulting from war and the break-up of the country, combined with ill-conceived populist policies and nationalization. While much of that was reversed in the 1980s, the decade was one of facile growth and one in which a different set of seeds was sown for the subsequent slowdown,” wrote economist Akbar Noman, in his 2015 Columbia University research paper.

The reign of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was a difficult economic period for Pakistan as it was fresh out of a war and was challenged with worldwide recession in exports, floods of 1974 and locust attacks, and Bhutto’s economic policies, including nationalization, didn’t help either.

“Until 1971 Pakistan didn’t have a chronic current account deficit, onwards from that year, there has been deficits every year,” said Khurram Husain, business and economy journalist, in an interview.

“His nationalization policies became the major reason for the loss of industrial units and the confidence of investors to invest in Pakistan. Meanwhile, his polices created misallocation of resources and the overall growth was declined, form 6.8% per annum in 1960’s to 4.8% per annum in 1970’s. Also, even though he introduced the land reforms, some criticize that his nationalization policies were feudal led, which were introduced to clip the wings of industrialist class that had grown tremendously in 1960’s,” read an article in Modern Diplomacy.

The situation back then has a lot of similarities when compared to Pakistan of 2023. The floods and global crisis have exacerbated the country’s problems to an extent where it stands at a crossroads and at the mercy of a financial institution.

“Inflation in the 1970s was triggered by these dramatic oil shocks. One that started in 1973, with the Arab embargo, and one toward the end of the decade with the Iranian revolution that led to a decrease in oil supply. In some ways that feels somewhat similar today, because Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has disrupted international oil markets,” read an article published in the Bloomberg.

Much like today, Pakistan didn’t have ample fiscal room to withstand the external pressures that mounted in the 1970s.

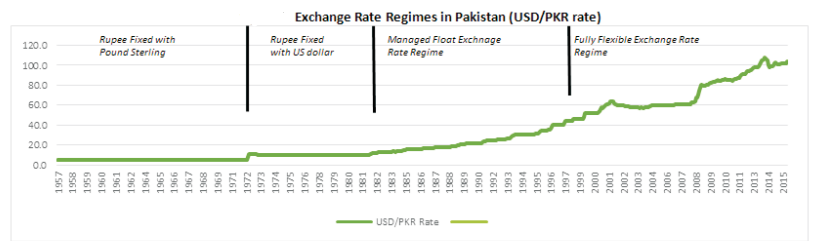

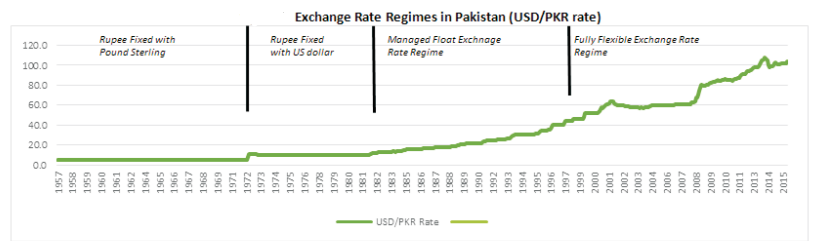

Source: SDPI

“Attempts to help the external sector pressures led to a 57% devaluation in 1972. This proved to be a major hit on public finances, which were already strained due to high defence expenditures. By the time Bhutto came to power in 1973, a drought was weighing down agriculture production while labour unrest and power shortages were hitting industrial production. As it turned out, the unbridled growth of the 1960s, driven by external aid, led to problems catalysed by the civil war and continued political unrest. That is when it became necessary for Pakistan to restructure its external debt,” writes Raza Agha, in an article for the Profit.

Source: Bank of Canada

Yet, there are key economic differences at global level between the two periods. “For instance, in the 1970s, ambivalence over how to fund the Vietnam War, which was unpopular, played a role in driving inflation. As for today, we had a once-in-a-century pandemic that destabilized the economy. And what we’re seeing is that this remarkable recovery in employment has not been entirely matched by a return of the supply chains that we need,” the Bloomberg article further added.

Way forward

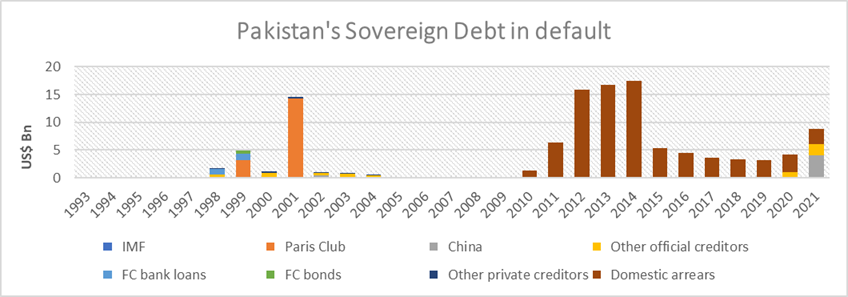

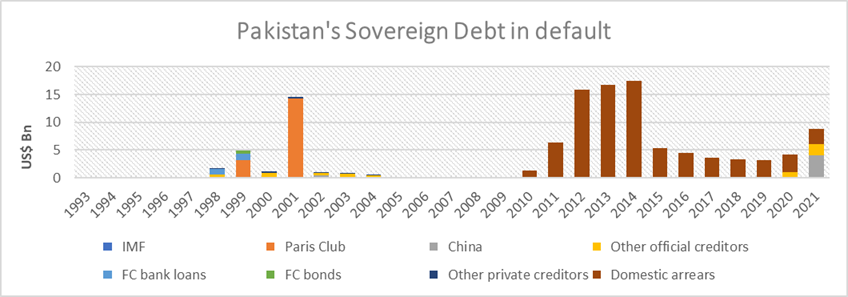

While the matter of immediate concern is gaining the IMF approval, Pakistan’s economic woes will continue as the debt burden has become unsustainable to a point where debt restructuring is a question of when rather than if.

Read More: Mounting Debt And Lack Of Alternatives Calls For A Debt Restructuring Of Pakistan’s Economy. But Would It Be Possible?

As per a report by RANE Risk Intelligence, “While Pakistan is likely to avoid a default in 2023, its debt woes will persist in the coming years. Political calculations will continue to influence economic policy, which means the government is unlikely to enact needed structural reforms before the next general elections.”

Further, the deteriorating security situation in the wake of the TTP’s resurgence can also take a toll on the country’s economy. “Political and economic instability will intensify the security risks in the country. Pakistan is already facing an increased threat from extremist militant groups like Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which has pledged to increase its attacks against security personnel and infrastructure in the country. Separatist groups like Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) may also intensify attacks against the government and infrastructure as economic grievances of Baloch people, allegedly deprived of the region's development gains, bolster their resolve,” the RANE report further added.

As per recent figures, released by the statistics bureau, inflation for January was recorded at 27.55 percent, highest since 1975. Further, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) reserves have also plunged to $3.09 billion, only sufficient to cover 20 days of imports.

Due to the bulk adjustment in currency and the subsequent fuel price hikes, experts are anticipating the inflation figures to breach the 30 percent barrier. This key drivers for the new wave of inflation would be commodities like fuel, edible oil and items for which Pakistan is a net importer.

In a recent report, the World Bank lowered Pakistan’s GDP growth forecast for 2023 to 2 percent, almost half of its earlier estimate.

Therefore, all eyes are on the Pakistan-IMF talks as the government is hopeful that the global financial institution will green light the $1 billion tranche and pave the way for other multilateral/bilateral funding.

Amidst all the chaos, experts have been pointing to the fact that this might be the worst economic crisis that the country has faced in the past 50 years. Therefore, it is worthwhile to explore that what transpired in the 1970s that many believe it to be a dark chapter in Pakistan’s economic history.

The situation back then has a lot of similarities when compared to Pakistan of 2023. The floods and global crisis have exacerbated the country’s problems to an extent where it stands at a crossroads and at the mercy of a financial institution.

Situation in 1970s

The era was marked with political turmoil and the devastation caused by a war that broke the country in to two pieces.

The decade started with a conflict that resulted in a major hit on foreign currency reserves which plummeted to $160 million in January 1971, and Pakistan was unable to fulfil its obligation to commercial creditors.

“Arguably, the seeds for the (economic) slowdown were sown in the 1970s with the disruptions resulting from war and the break-up of the country, combined with ill-conceived populist policies and nationalization. While much of that was reversed in the 1980s, the decade was one of facile growth and one in which a different set of seeds was sown for the subsequent slowdown,” wrote economist Akbar Noman, in his 2015 Columbia University research paper.

The reign of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was a difficult economic period for Pakistan as it was fresh out of a war and was challenged with worldwide recession in exports, floods of 1974 and locust attacks, and Bhutto’s economic policies, including nationalization, didn’t help either.

“Until 1971 Pakistan didn’t have a chronic current account deficit, onwards from that year, there has been deficits every year,” said Khurram Husain, business and economy journalist, in an interview.

“His nationalization policies became the major reason for the loss of industrial units and the confidence of investors to invest in Pakistan. Meanwhile, his polices created misallocation of resources and the overall growth was declined, form 6.8% per annum in 1960’s to 4.8% per annum in 1970’s. Also, even though he introduced the land reforms, some criticize that his nationalization policies were feudal led, which were introduced to clip the wings of industrialist class that had grown tremendously in 1960’s,” read an article in Modern Diplomacy.

The situation back then has a lot of similarities when compared to Pakistan of 2023. The floods and global crisis have exacerbated the country’s problems to an extent where it stands at a crossroads and at the mercy of a financial institution.

“Inflation in the 1970s was triggered by these dramatic oil shocks. One that started in 1973, with the Arab embargo, and one toward the end of the decade with the Iranian revolution that led to a decrease in oil supply. In some ways that feels somewhat similar today, because Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has disrupted international oil markets,” read an article published in the Bloomberg.

Much like today, Pakistan didn’t have ample fiscal room to withstand the external pressures that mounted in the 1970s.

Source: SDPI

“Attempts to help the external sector pressures led to a 57% devaluation in 1972. This proved to be a major hit on public finances, which were already strained due to high defence expenditures. By the time Bhutto came to power in 1973, a drought was weighing down agriculture production while labour unrest and power shortages were hitting industrial production. As it turned out, the unbridled growth of the 1960s, driven by external aid, led to problems catalysed by the civil war and continued political unrest. That is when it became necessary for Pakistan to restructure its external debt,” writes Raza Agha, in an article for the Profit.

Source: Bank of Canada

Yet, there are key economic differences at global level between the two periods. “For instance, in the 1970s, ambivalence over how to fund the Vietnam War, which was unpopular, played a role in driving inflation. As for today, we had a once-in-a-century pandemic that destabilized the economy. And what we’re seeing is that this remarkable recovery in employment has not been entirely matched by a return of the supply chains that we need,” the Bloomberg article further added.

Way forward

While the matter of immediate concern is gaining the IMF approval, Pakistan’s economic woes will continue as the debt burden has become unsustainable to a point where debt restructuring is a question of when rather than if.

Read More: Mounting Debt And Lack Of Alternatives Calls For A Debt Restructuring Of Pakistan’s Economy. But Would It Be Possible?

As per a report by RANE Risk Intelligence, “While Pakistan is likely to avoid a default in 2023, its debt woes will persist in the coming years. Political calculations will continue to influence economic policy, which means the government is unlikely to enact needed structural reforms before the next general elections.”

Further, the deteriorating security situation in the wake of the TTP’s resurgence can also take a toll on the country’s economy. “Political and economic instability will intensify the security risks in the country. Pakistan is already facing an increased threat from extremist militant groups like Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), which has pledged to increase its attacks against security personnel and infrastructure in the country. Separatist groups like Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) may also intensify attacks against the government and infrastructure as economic grievances of Baloch people, allegedly deprived of the region's development gains, bolster their resolve,” the RANE report further added.