Note: This extract is from the author’s coming autobiography titled Not The Whole Truth: My Life and Times.

Click here for part IV

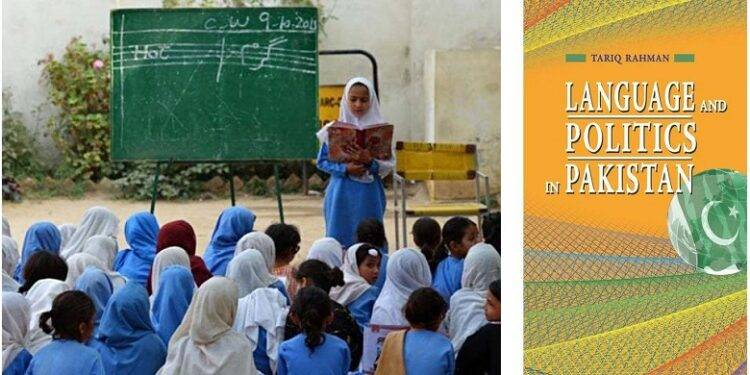

By January 1995 the manuscript of Language and Politics in Pakistan had been submitted to the Oxford University Press. Its proofs came to me when I was in America in early 1996 so I thought it would be out by the time I returned to Pakistan in June. However, it was November 1996 and my book was still not out. To add to my frustration the Islamists had forced the Oxford University Press office in Islamabad to close down as some book, probably part of children’s’ course, contained material which they considered offensive. Anyway, at last the OUP opened the office and it was in middle November that I held copies of Language and Politics in Pakistan in my hands. I was filled with a quiet joy I could not express. I took it home and Hana, never restrained in her expression of joy, was ecstatic with pleasure. My mother – the book was dedicated to my parents – also beamed with satisfaction. My father expressed his happiness by telling me to thank God. This was his only way of doing so. The children, aided by their mother, asked for a treat and so did Azam when he came to know about it. I gave the first copy, other than the one I kept for ourselves at home, to Dr. Inayatullah in his house. I respected his political analysis very much and hoped that he would review the book. He disappointed me by not reviewing it himself but he did get it reviewed in the Social Sciences Forum. But Language and Politics was reviewed by many people. Khalid Ahmad of the Friday Times gave it high praise and every major English-Language publication in Pakistan reviewed it. It was also reviewed in major South Asia and linguistic journals abroad. Talat Hussain invited me to his TV programme to talk about it and the OUP soon told me that they would print a paperback edition. By 2003, a number of paperback editions had been printed. The book also got the Pitras Bukhari Award for being the best book in English in the year by the Pakistan Academy of Letters. Personally, I thought the award was wrongly given since this was not a literary book. I was also given an award for the same book, this time for the social sciences, by the National Book Council. This was the second award for it and it was Dr. Sikandar Hayat of the History Department at QAU who had shown me my name as the recipient of this award. I had never known I was in the running for it at all. However, the cheque they sent me was for Rs. 50,000 whereas the more prestigious Pitras Bukhari Award was only worth Rs. 20,000 which came two months later. However, the Pitras Bukhari award also carried a shield and a certificate which I did not collect till 2019 when, after seeing the shield with Athar Tahir, I thought I should also collect mine. That it was still there was a minor miracle for me.

But I am anticipating. To go back to UT Austin in 1995-96, after some initial dithering, I decided to write another book, this time on the history of language-teaching among the Muslims of South Asia. So, as soon as I returned to Pakistan, and even before the previous book was published, I started working on it. One day, as I sat in my SDPI office, a lean, sharp-looking young man came to visit me. His name was Ashfaq Sadiq and he had been recommended by my colleague, Dr. Rukhsana Quamber – sister of my army friend Naveed Quamber with whom I had travelled from Nowshera to Pindi during the 1971 War. Ashfaq Sadiq told me that he wanted to work only to get experience. I said I could hire him as my personal research assistant as I needed source material from all over the country. I could not give him a monthly fixed salary but I would pay his travelling expenses, work-related phone bills and even pay him for the items be brought for me. He agreed and I employed him. He turned out to be very resourceful and efficient. I sent him on a research tour to Sindh and Peshawar and he brought useful material from there. However, I often felt that he was not scrupulous about some things. Even so I recommended him to Shahrukh who became the Executive Director of SDPI in 1997 when Banuri’s term expired. Much later I heard that he had used a pistol or threatened someone with it, brought a girl in the hostel and taken SDPI funds and not returned them because he stayed back in Britain when he went there on a visit. All this came as a surprise to me but, because he had worked hard for me, I thanked him in my book.

Among other things, I wanted to collect material on the role and position of Urdu in India after 1947. This became possible as my mother ardently desired to go to India to meet her ailing sister, nephew and his family. I volunteered to take her with me. Our historic trip together has been described in the last chapter in this autobiography so I will only mention my trip to Delhi for research on language. I went with my cousin Khalid Bhai and reached Delhi where, after registering with the police, we started looking for the IIT. This too turned out to be difficult and we were tired and hungry when we finally came to the IIT and started looking for Dr Makarand Paranjape. I had never seen him but had communicated with him by e-mail. He had invited me to the IIT to stay there and I had rung him up from Shahabad. Hence, I was very relieved when I found him. He seemed so mild, kind and intelligent that I felt confident and elated that he was my host. He took me and Khalid Bhai to the guest house of the IIT. This was a huge circular building with rooms all facing a veranda and open space outside. There was light in the rooms and I loved them. The dining room was large and clean and there was a sitting room with a T.V. I and Khalid ate something – leftovers mostly – with relish and then I bid Khalid goodbye. I gave him a parting gift of cash for his children but he, proud and hospitable as he was, returned it all in even greater measure in gifts for my family.

That afternoon I wandered around in the huge open spaces of the IIT enjoying the sights and sounds. I merged in easily as I spoke the same language as the others. Of course, I called it Urdu and they called it Hindi but we really used most words in common, our body language was the same and we looked alike. I personally was fairer than most Indians but then I was like the Pathans in Pakistan – different from Punjabis, Sindhis and Muhajirs. In India too Kashmiris were like me as were some other people from the north. So, I did not feel like an alien. However, there was a bomb blast in South India just before the elections and the Pakistani ISI was blamed by the Indian T.V. This worried me and I started feeling my Muslim and Pakistani identity as a source of anxiety for me though nobody ever said anything negative to me. Indeed, everybody was most welcoming, cordial and courteous. Hence, I went about collecting material for my book with great enthusiasm. I went to the Anjuman-e-Taraqqi-e-Urdu where Khalique Anjum welcomed me almost as if I were a VIP. He told me that Iftikhar Arif had rung him up to take care of me. I was incredulous but showed no feelings. He gave me as much material as he could including a manuscript he had prepared on the Gujral Report on Urdu. I also met Harish Narang whom I had met when he had visited Chandramohan in Sheffield. He had published my short stories in Delhi in 1989. Now he was the Chairman of the English Department at JNU. Meanwhile Makarand invited me to dinner at his house and presented with a book on Buddhism. I told him that the Dhammapada by Gautama Buddha had interested me since the age of twenty-two. I had read the verses and framed them in my room and even quoted them in Language and Politics in Pakistan which he had reviewed in The Hindu. He told me that that was the reason he had given me a book on Buddhism.

I was also invited to lecture at the IIT, the Jamia Millia Islamia and at the JNU. At the Jamia somebody questioned me on my book A History of Pakistani Literature in English which I regarded as something of a fossil. At the IIT Alok Rai, the grandson of Premchand, had a meeting with me. The JNU lecture came when I was actually living there and it was a success because the hall was nearly full and many people came up with good questions. Besides lectures, I also visited a book fair – a huge, colourful, meena bazaar kind of affair with more spicy delicacies and smart girls on scooters, than books. I was also invited to a house in the JNU campus, probably Narang’s, where I met Dr. Kaleem Bahadur, the author of a book on the Jamat-i-Islami. He was from an area my father often mentioned in his reminiscences about India.

I was happy at IIT guest house where the cooking was completely vegetarian. Instead of meat they used cottage cheese (paneer) and I loved their palak paneer (spinach and cheese) as well as other paneer dishes. I also enjoyed the openness of the rooms and the grounds around the guest house. As for company, I knew one or two people. There was an Englishman in quest of the Buddhist trail whom I often talked to. But Makarand was my main friend. However, even he could not prevent the IIT authorities from giving me notice since they needed all the rooms for an upcoming event. So, most reluctantly, I asked Narang for the favour of accommodating me at the JNU guest house. He arranged it for me and I moved there. Here the room was in a corridor and not as full of light as the one in the IIT. The food, though there were meat dishes, was not as good and, of course, there was no company at all. I did, however, inflict myself on Dr. Naseer Uddin, Professor of Urdu, whose house was on the campus. He could not violate norms of politeness so much as to tell me not to visit him but it was clear to me that I was not welcome. Yet, so lonely was I in the evening that I did intrude upon him twice or thrice. The end of this visit has been described in the last chapter so I will not repeat the details here.

Back again in Daira and QAU I started working on my book in earnest. As data poured in, the chapters started taking a rough outline. I now developed a questionnaire which I started getting filled out in government Urdu-medium schools, religious seminaries (madrasas) and elite English-medium schools. Students sometimes volunteered to help me. For instance, a major from the Army Education Corps, who was studying research methodology for his M. Phil from me, got many questionnaires filled out at the Military College Jhelum. Another helped me in meeting maulvis in the madrasas. As before, sometimes I travelled with my family and sometimes alone. A trip to Swat has a special place in my memory. I hired a vehicle in which all four of us and Ammi went to Saidu Sharif. Here I delivered a lecture at the local government college and visited madrasas where the medium of instruction was Pashto. Then we drove to Kalam along the snaking road clinging to the mountains. Below us was the gurgling of the Swat River as it flowed down to the sea. At some places the sound changed to a roar as the river rushed past. We stopped to have fried trout and then entered the bazaar of Kalam. The house we stayed in looked directly across a gleaming white majestic peak at which I kept gazing in sheer awe because of its romantic beauty. It was a rare sight. Our host, who was a relative of a lecturer who had invited us to Swat, displayed the fabled Pathan hospitality. Next day Dr and Mrs. Joan Baart, from the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL), gave us a good lunch in a hotel. Baart’s research assistant. Zaman Sagar, took us to the Kalami-speaking area up to a huge glacier from where we had to turn back. Then we drove down to Saidu Sharif and, without stopping there, all the way back to Pindi. Mother really enjoyed the trip as she enjoyed all trips with us.

The trip to Swat was part of the research I was doing on schools for the Asian Development Bank. They had given the project to the SDPI, I believe, which passed it on to me. I had written no proposal for it nor had I competed for it. My total budget was Rs 100, 000 out of which Ashfaq Sadiq got most of the money since I sent him to Sindh and Peshawar to get material for this project which I would also use for my book. This was the only time I got any project at the SDPI and, as I was told later, it was not well-paid in comparative terms. People got budgets of millions. But then they had to write proposals, compete and work to please the donors. I did nothing of the kind. I merely gave them the study I was doing anyway for my book making it clear that I would use the same data for my book. Meanwhile the one-day salary from the SDPI was very helpful. It was then that Tariq Banuri made me the chief editor at SDPI responsible for both the Urdu and the English sections. He wanted to give me three day’s salary but I felt it would make me more of an employee of the SDPI than QAU which I did not like. What I had most misgivings about was my independence. Being a paid editor would make me subservient to the SDPI management and responsible to the executive director in the way employees are. This I could not brook. Therefore, I suggested I should be made an honorary, unpaid editor. I did, however, accept a pay raise in the position of the research advisor but only a modest rise of 5000 rupees (1.5 days salary) but the editing would be free. Moreover, I would give the SDPI the same time as I did before though I would concern myself with editing now. When Shahrukh became the executive director, this was the state of affairs.

In these years I travelled very often to Karachi and stayed with Shakeel and his wife Humaira since Chacha Mian lived with them now. Riaz and his wife Ayesha lived downstairs but the relations between the wives, and even the two brothers, were cool. The children played together and I always gave them a treat. One of these winters I decided to go as far inside Sindh as possible. As my friend Khalid Khan, now a lieutenant colonel, lived in Hyderabad, it was fun to stay with him. As for the trip beyond Hyderabad I requested Brigadier Junaid, then chief of the ISI in Karachi, to help me. Junaid was the husband of one of my wife’s cousins and knew me very well. He sent word to one of his sector commanders in Hyderabad who gave me a jeep with a civilian officer to accompany me. We went to madrasas beyond Hyderabad up to Hala and then on to a college of the Jamat-i-Islami in Mansurah. The maulvis were generally very hospitable though they did not always allow me to get the questionnaires filled out from their students. They showed me their books and answered my questions. Meanwhile, unfortunately, the civilian officer became something of a headache for me. He started asking the typical spying questions about militancy and so on. This, I felt, would make the maulvis shut up about my questions about language teaching and my research would suffer. So, while I had to tag him along in Hyderabad city also, I dropped him as soon as I could. In subsequent trips Khalid helped me even more since by then, having retired from the army, he was in Preston University as an administrator. He sent me with one of his colleagues to Cadet College Pitaro, to colleges where there were Sindhi-speaking students and even the Jamat Khanas of the Agha Khani Ismaili community.

Click here for part IV

By January 1995 the manuscript of Language and Politics in Pakistan had been submitted to the Oxford University Press. Its proofs came to me when I was in America in early 1996 so I thought it would be out by the time I returned to Pakistan in June. However, it was November 1996 and my book was still not out. To add to my frustration the Islamists had forced the Oxford University Press office in Islamabad to close down as some book, probably part of children’s’ course, contained material which they considered offensive. Anyway, at last the OUP opened the office and it was in middle November that I held copies of Language and Politics in Pakistan in my hands. I was filled with a quiet joy I could not express. I took it home and Hana, never restrained in her expression of joy, was ecstatic with pleasure. My mother – the book was dedicated to my parents – also beamed with satisfaction. My father expressed his happiness by telling me to thank God. This was his only way of doing so. The children, aided by their mother, asked for a treat and so did Azam when he came to know about it. I gave the first copy, other than the one I kept for ourselves at home, to Dr. Inayatullah in his house. I respected his political analysis very much and hoped that he would review the book. He disappointed me by not reviewing it himself but he did get it reviewed in the Social Sciences Forum. But Language and Politics was reviewed by many people. Khalid Ahmad of the Friday Times gave it high praise and every major English-Language publication in Pakistan reviewed it. It was also reviewed in major South Asia and linguistic journals abroad. Talat Hussain invited me to his TV programme to talk about it and the OUP soon told me that they would print a paperback edition. By 2003, a number of paperback editions had been printed. The book also got the Pitras Bukhari Award for being the best book in English in the year by the Pakistan Academy of Letters. Personally, I thought the award was wrongly given since this was not a literary book. I was also given an award for the same book, this time for the social sciences, by the National Book Council. This was the second award for it and it was Dr. Sikandar Hayat of the History Department at QAU who had shown me my name as the recipient of this award. I had never known I was in the running for it at all. However, the cheque they sent me was for Rs. 50,000 whereas the more prestigious Pitras Bukhari Award was only worth Rs. 20,000 which came two months later. However, the Pitras Bukhari award also carried a shield and a certificate which I did not collect till 2019 when, after seeing the shield with Athar Tahir, I thought I should also collect mine. That it was still there was a minor miracle for me.

But I am anticipating. To go back to UT Austin in 1995-96, after some initial dithering, I decided to write another book, this time on the history of language-teaching among the Muslims of South Asia. So, as soon as I returned to Pakistan, and even before the previous book was published, I started working on it. One day, as I sat in my SDPI office, a lean, sharp-looking young man came to visit me. His name was Ashfaq Sadiq and he had been recommended by my colleague, Dr. Rukhsana Quamber – sister of my army friend Naveed Quamber with whom I had travelled from Nowshera to Pindi during the 1971 War. Ashfaq Sadiq told me that he wanted to work only to get experience. I said I could hire him as my personal research assistant as I needed source material from all over the country. I could not give him a monthly fixed salary but I would pay his travelling expenses, work-related phone bills and even pay him for the items be brought for me. He agreed and I employed him. He turned out to be very resourceful and efficient. I sent him on a research tour to Sindh and Peshawar and he brought useful material from there. However, I often felt that he was not scrupulous about some things. Even so I recommended him to Shahrukh who became the Executive Director of SDPI in 1997 when Banuri’s term expired. Much later I heard that he had used a pistol or threatened someone with it, brought a girl in the hostel and taken SDPI funds and not returned them because he stayed back in Britain when he went there on a visit. All this came as a surprise to me but, because he had worked hard for me, I thanked him in my book.

I was invited to a house in the JNU campus, probably Narang’s, where I met Dr. Kaleem Bahadur, the author of a book on the Jamat-i-Islami. He was from an area my father often mentioned in his reminiscences about India

Among other things, I wanted to collect material on the role and position of Urdu in India after 1947. This became possible as my mother ardently desired to go to India to meet her ailing sister, nephew and his family. I volunteered to take her with me. Our historic trip together has been described in the last chapter in this autobiography so I will only mention my trip to Delhi for research on language. I went with my cousin Khalid Bhai and reached Delhi where, after registering with the police, we started looking for the IIT. This too turned out to be difficult and we were tired and hungry when we finally came to the IIT and started looking for Dr Makarand Paranjape. I had never seen him but had communicated with him by e-mail. He had invited me to the IIT to stay there and I had rung him up from Shahabad. Hence, I was very relieved when I found him. He seemed so mild, kind and intelligent that I felt confident and elated that he was my host. He took me and Khalid Bhai to the guest house of the IIT. This was a huge circular building with rooms all facing a veranda and open space outside. There was light in the rooms and I loved them. The dining room was large and clean and there was a sitting room with a T.V. I and Khalid ate something – leftovers mostly – with relish and then I bid Khalid goodbye. I gave him a parting gift of cash for his children but he, proud and hospitable as he was, returned it all in even greater measure in gifts for my family.

That afternoon I wandered around in the huge open spaces of the IIT enjoying the sights and sounds. I merged in easily as I spoke the same language as the others. Of course, I called it Urdu and they called it Hindi but we really used most words in common, our body language was the same and we looked alike. I personally was fairer than most Indians but then I was like the Pathans in Pakistan – different from Punjabis, Sindhis and Muhajirs. In India too Kashmiris were like me as were some other people from the north. So, I did not feel like an alien. However, there was a bomb blast in South India just before the elections and the Pakistani ISI was blamed by the Indian T.V. This worried me and I started feeling my Muslim and Pakistani identity as a source of anxiety for me though nobody ever said anything negative to me. Indeed, everybody was most welcoming, cordial and courteous. Hence, I went about collecting material for my book with great enthusiasm. I went to the Anjuman-e-Taraqqi-e-Urdu where Khalique Anjum welcomed me almost as if I were a VIP. He told me that Iftikhar Arif had rung him up to take care of me. I was incredulous but showed no feelings. He gave me as much material as he could including a manuscript he had prepared on the Gujral Report on Urdu. I also met Harish Narang whom I had met when he had visited Chandramohan in Sheffield. He had published my short stories in Delhi in 1989. Now he was the Chairman of the English Department at JNU. Meanwhile Makarand invited me to dinner at his house and presented with a book on Buddhism. I told him that the Dhammapada by Gautama Buddha had interested me since the age of twenty-two. I had read the verses and framed them in my room and even quoted them in Language and Politics in Pakistan which he had reviewed in The Hindu. He told me that that was the reason he had given me a book on Buddhism.

I was also invited to lecture at the IIT, the Jamia Millia Islamia and at the JNU. At the Jamia somebody questioned me on my book A History of Pakistani Literature in English which I regarded as something of a fossil. At the IIT Alok Rai, the grandson of Premchand, had a meeting with me. The JNU lecture came when I was actually living there and it was a success because the hall was nearly full and many people came up with good questions. Besides lectures, I also visited a book fair – a huge, colourful, meena bazaar kind of affair with more spicy delicacies and smart girls on scooters, than books. I was also invited to a house in the JNU campus, probably Narang’s, where I met Dr. Kaleem Bahadur, the author of a book on the Jamat-i-Islami. He was from an area my father often mentioned in his reminiscences about India.

I was happy at IIT guest house where the cooking was completely vegetarian. Instead of meat they used cottage cheese (paneer) and I loved their palak paneer (spinach and cheese) as well as other paneer dishes. I also enjoyed the openness of the rooms and the grounds around the guest house. As for company, I knew one or two people. There was an Englishman in quest of the Buddhist trail whom I often talked to. But Makarand was my main friend. However, even he could not prevent the IIT authorities from giving me notice since they needed all the rooms for an upcoming event. So, most reluctantly, I asked Narang for the favour of accommodating me at the JNU guest house. He arranged it for me and I moved there. Here the room was in a corridor and not as full of light as the one in the IIT. The food, though there were meat dishes, was not as good and, of course, there was no company at all. I did, however, inflict myself on Dr. Naseer Uddin, Professor of Urdu, whose house was on the campus. He could not violate norms of politeness so much as to tell me not to visit him but it was clear to me that I was not welcome. Yet, so lonely was I in the evening that I did intrude upon him twice or thrice. The end of this visit has been described in the last chapter so I will not repeat the details here.

Back again in Daira and QAU I started working on my book in earnest. As data poured in, the chapters started taking a rough outline. I now developed a questionnaire which I started getting filled out in government Urdu-medium schools, religious seminaries (madrasas) and elite English-medium schools. Students sometimes volunteered to help me. For instance, a major from the Army Education Corps, who was studying research methodology for his M. Phil from me, got many questionnaires filled out at the Military College Jhelum. Another helped me in meeting maulvis in the madrasas. As before, sometimes I travelled with my family and sometimes alone. A trip to Swat has a special place in my memory. I hired a vehicle in which all four of us and Ammi went to Saidu Sharif. Here I delivered a lecture at the local government college and visited madrasas where the medium of instruction was Pashto. Then we drove to Kalam along the snaking road clinging to the mountains. Below us was the gurgling of the Swat River as it flowed down to the sea. At some places the sound changed to a roar as the river rushed past. We stopped to have fried trout and then entered the bazaar of Kalam. The house we stayed in looked directly across a gleaming white majestic peak at which I kept gazing in sheer awe because of its romantic beauty. It was a rare sight. Our host, who was a relative of a lecturer who had invited us to Swat, displayed the fabled Pathan hospitality. Next day Dr and Mrs. Joan Baart, from the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL), gave us a good lunch in a hotel. Baart’s research assistant. Zaman Sagar, took us to the Kalami-speaking area up to a huge glacier from where we had to turn back. Then we drove down to Saidu Sharif and, without stopping there, all the way back to Pindi. Mother really enjoyed the trip as she enjoyed all trips with us.

The trip to Swat was part of the research I was doing on schools for the Asian Development Bank. They had given the project to the SDPI, I believe, which passed it on to me. I had written no proposal for it nor had I competed for it. My total budget was Rs 100, 000 out of which Ashfaq Sadiq got most of the money since I sent him to Sindh and Peshawar to get material for this project which I would also use for my book. This was the only time I got any project at the SDPI and, as I was told later, it was not well-paid in comparative terms. People got budgets of millions. But then they had to write proposals, compete and work to please the donors. I did nothing of the kind. I merely gave them the study I was doing anyway for my book making it clear that I would use the same data for my book. Meanwhile the one-day salary from the SDPI was very helpful. It was then that Tariq Banuri made me the chief editor at SDPI responsible for both the Urdu and the English sections. He wanted to give me three day’s salary but I felt it would make me more of an employee of the SDPI than QAU which I did not like. What I had most misgivings about was my independence. Being a paid editor would make me subservient to the SDPI management and responsible to the executive director in the way employees are. This I could not brook. Therefore, I suggested I should be made an honorary, unpaid editor. I did, however, accept a pay raise in the position of the research advisor but only a modest rise of 5000 rupees (1.5 days salary) but the editing would be free. Moreover, I would give the SDPI the same time as I did before though I would concern myself with editing now. When Shahrukh became the executive director, this was the state of affairs.

In these years I travelled very often to Karachi and stayed with Shakeel and his wife Humaira since Chacha Mian lived with them now. Riaz and his wife Ayesha lived downstairs but the relations between the wives, and even the two brothers, were cool. The children played together and I always gave them a treat. One of these winters I decided to go as far inside Sindh as possible. As my friend Khalid Khan, now a lieutenant colonel, lived in Hyderabad, it was fun to stay with him. As for the trip beyond Hyderabad I requested Brigadier Junaid, then chief of the ISI in Karachi, to help me. Junaid was the husband of one of my wife’s cousins and knew me very well. He sent word to one of his sector commanders in Hyderabad who gave me a jeep with a civilian officer to accompany me. We went to madrasas beyond Hyderabad up to Hala and then on to a college of the Jamat-i-Islami in Mansurah. The maulvis were generally very hospitable though they did not always allow me to get the questionnaires filled out from their students. They showed me their books and answered my questions. Meanwhile, unfortunately, the civilian officer became something of a headache for me. He started asking the typical spying questions about militancy and so on. This, I felt, would make the maulvis shut up about my questions about language teaching and my research would suffer. So, while I had to tag him along in Hyderabad city also, I dropped him as soon as I could. In subsequent trips Khalid helped me even more since by then, having retired from the army, he was in Preston University as an administrator. He sent me with one of his colleagues to Cadet College Pitaro, to colleges where there were Sindhi-speaking students and even the Jamat Khanas of the Agha Khani Ismaili community.