A frightening silence is maintained in the country on Balochistan. It is described as an information black hole. However, a recently published research paper, titled Girls’ education in Balochistan, Pakistan: exploring a postcolonial Islamic governmentality’ offers some hope to the province.

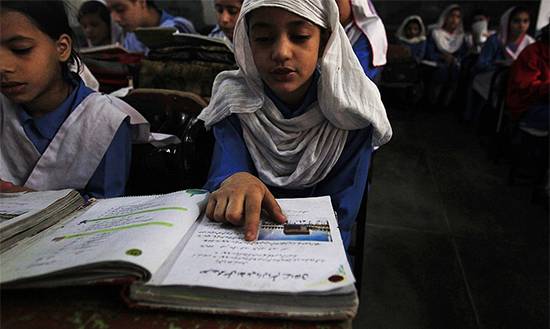

Authored by Javed Anwar, Peter Kelly and Emily Gray, and published in British Journal of Sociology of Education, the paper is an effort to understand gender disparities in rural schools of Balochistan.

Taking advantage of substantive political theories like Michel Foucault’s theory of governmentality, Mitchell Dean’s illiberal governmentalities, and Salehin’s pious governmentality in Bangladesh, it develops a productive theoretical approach of ‘post-colonial Islamic governmentality’ to broaden the discourse on education governance in Pakistan and rest of the world. The authors examine the ways in which the transnational organisations, colonial legacies and politics and culture of particular version of religious practices in different ways attempt to govern and shape girls’ access and participation in rural and remote areas. They suggest that at the intersection of Islamic principles and practices and modern education, the sustainable development goals can be achieved in the rural locations.

This qualitative study used data collected from 19 individuals and five focus groups through semi-structured interviews. The interviewees selected for data collection were involved in education policy and governance of Balochistan at different hierarchical levels.

Contending that the political rationalities mediate between Islamic and secular forms of governance, the paper looks at the global influences of education policy with regard to United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), conceptions of neoliberal globalisations along with the bearings of colonial legacies and religion on framing national, provincial and district policy narratives.

Balochistan has been chosen as a case study to investigate the problem of girls’ education as it presents a bird’s eye view of governing challenges due to its rural and urban and gender disparities in schools.

The study recommends two key applications for the conceptual framework of post-colonial Islamic governmentality: first, this framework might be useful in realising the promise of long-term progress in girls' education; second, it declares that this innovative framework is an attempt to contribute to academic debates in Foucault’s theoretical legacies.

Post-colonialism, in the paper, is understood in two different ways: first, the period following the departure of the British colonial rulers; second, as a theoretical lens it unfolds the ways through which geography, politics, social, and cultural lives are understood both within previously colonised as well as colonising nations.

Further, the paper stresses on two key education policy influences and policy shifts during the Cold War and the War on Terror. During the military regime of General Ziaul Haq, the objective of Islamisation was achieved through the development and implementation of the Education Policy of 1979. Pakistan committed to the global agendas of Education For All (EFA) and Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in the following years, creating hope for improved girls' education and closing the gender gap.

Despite these assurances, there has been inadequate improvement in the field of female education due to Zia's rigorous Islamisation policies. Conservative lobbies gained disproportionate representation in the policy arena that led to gender segregation and women/girls’ marginalisation across the country.

General Pervez Musharraf pressed for moderate Islam and attempted to accord more space to women/girls in the public sphere through multiple initiatives. This shift in the education policy attracted the international donors and transnational organisations to assist the girls’ education policy and practice. There was also an emphasis on the decentralisation of governance through the initiatives of Devolution of Powers Ordinance (2001), and later 18th constitutional amendment (2010) which transferred the education policy governance responsibilities to the provinces and districts. National Education Policy 2009, aided by tremendous technical and financial support of international donors could not achieve education-related UN millennium development goals (MGD) by a great margin. Pakistan recommitted to the UN sustainable development goals (SDG) objectives in 2015 and also made it a part of its national development strategy. Nonetheless, all gender inequalities across the urban-rural split and socioeconomic class remain significant, and are expected to worsen as a result of Covid 19.

The paper argues that the ‘sparse rurality’ of Balochistan poses multiple challenges. There are around 3,974 schools for girls and 9,700 for boys. Given the scattered population of the province more funds are required to educate all the children, including girls. The paper suggests for alternative solutions of mobile schools or flexible schools in the rural areas.

Moreover, in the absence of certified teachers, pesh imams of local mosques frequently teach children. The local communities trust them due to their role in spiritual, social and community activities. In such circumstances, the paper advocates for imams to be mainstreamed, by training them in contemporary education.

In this case, two advantages of application of conceptual framework of post-colonial Islamic governmentality are suggested: first, the participation of pesh imam improves girls' opportunities in rural areas to receive modern education as well as religious instruction; and second, it brings local religious actors, development organisations and public institutions closer, allowing for a productive relationship between religious and secular-modern forces.

The paper also discusses the challenges of lack of availability and low standard of public schools, which results in a growing tendency of girls’ enrollment in informal madrassahs. Around 3,200 of the province's numerous madrassahs are officially registered with the government. These madrassahs and/or mosques with pesh imams -- as teachers in locations where girls’ schools and female teachers are not available -- can become schools for girls up to levels primary level and beyond.

It highlights that social and gender relations in Balochistan are guided and understood by the discourse and practice of Balochi riwaj (traditions) in the province, whereby women/girls are thought to be honour and dignity of the family, clan and tribe. Islamic norms and practices interplaying with riwaj and shape girls’ schooling. The paper also shows that the intersection of local cultures and Islamic practices do not stop girls from going to school.

Balochistan’s culture in fact facilitates and supports girls’ education. It accommodates female teachers and their families in school premises to ensure girls get education. The decisions are taken by village malik (elder), and governance of girls’ schools strengthens his authority in the area.

This paper also provokes many questions: for example, what will be the mechanism of equating the qualification and skills of pesh imam to enable him to teach Science, IT and other courses in addition to spiritual? Will pesh imams stay in the same village if they are provided employment as teacher? How will malik find space in the education policy making? How will girls in primary education taught by imams pursue higher education? Girls may have to relocate to attend colleges and universities. In this sense, postcolonial Islamic governmentality as a theoretical approach can be applied at different junctures and locations to analyse girls’ education in the country.

The paper provides significant insights. It provides an academic understanding about the problem of girls’ schooling. It merits a thorough reading by the policymakers, scholars, academics, researchers, policy analysts and stakeholders to understand policy problems with regard to girls’ education in the country.

The writer is an undergrad student at Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad. He tweets at @amin_salal

Authored by Javed Anwar, Peter Kelly and Emily Gray, and published in British Journal of Sociology of Education, the paper is an effort to understand gender disparities in rural schools of Balochistan.

Taking advantage of substantive political theories like Michel Foucault’s theory of governmentality, Mitchell Dean’s illiberal governmentalities, and Salehin’s pious governmentality in Bangladesh, it develops a productive theoretical approach of ‘post-colonial Islamic governmentality’ to broaden the discourse on education governance in Pakistan and rest of the world. The authors examine the ways in which the transnational organisations, colonial legacies and politics and culture of particular version of religious practices in different ways attempt to govern and shape girls’ access and participation in rural and remote areas. They suggest that at the intersection of Islamic principles and practices and modern education, the sustainable development goals can be achieved in the rural locations.

This qualitative study used data collected from 19 individuals and five focus groups through semi-structured interviews. The interviewees selected for data collection were involved in education policy and governance of Balochistan at different hierarchical levels.

Contending that the political rationalities mediate between Islamic and secular forms of governance, the paper looks at the global influences of education policy with regard to United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), conceptions of neoliberal globalisations along with the bearings of colonial legacies and religion on framing national, provincial and district policy narratives.

Balochistan has been chosen as a case study to investigate the problem of girls’ education as it presents a bird’s eye view of governing challenges due to its rural and urban and gender disparities in schools.

The paper argues that the ‘sparse rurality’ of Balochistan poses multiple challenges. There are around 3,974 schools for girls and 9,700 for boys. Given the scattered population of the province more funds are required to educate all the children, including girls. The paper suggests for alternative solutions of mobile schools or flexible schools in the rural areas.

The study recommends two key applications for the conceptual framework of post-colonial Islamic governmentality: first, this framework might be useful in realising the promise of long-term progress in girls' education; second, it declares that this innovative framework is an attempt to contribute to academic debates in Foucault’s theoretical legacies.

Post-colonialism, in the paper, is understood in two different ways: first, the period following the departure of the British colonial rulers; second, as a theoretical lens it unfolds the ways through which geography, politics, social, and cultural lives are understood both within previously colonised as well as colonising nations.

Further, the paper stresses on two key education policy influences and policy shifts during the Cold War and the War on Terror. During the military regime of General Ziaul Haq, the objective of Islamisation was achieved through the development and implementation of the Education Policy of 1979. Pakistan committed to the global agendas of Education For All (EFA) and Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in the following years, creating hope for improved girls' education and closing the gender gap.

Despite these assurances, there has been inadequate improvement in the field of female education due to Zia's rigorous Islamisation policies. Conservative lobbies gained disproportionate representation in the policy arena that led to gender segregation and women/girls’ marginalisation across the country.

General Pervez Musharraf pressed for moderate Islam and attempted to accord more space to women/girls in the public sphere through multiple initiatives. This shift in the education policy attracted the international donors and transnational organisations to assist the girls’ education policy and practice. There was also an emphasis on the decentralisation of governance through the initiatives of Devolution of Powers Ordinance (2001), and later 18th constitutional amendment (2010) which transferred the education policy governance responsibilities to the provinces and districts. National Education Policy 2009, aided by tremendous technical and financial support of international donors could not achieve education-related UN millennium development goals (MGD) by a great margin. Pakistan recommitted to the UN sustainable development goals (SDG) objectives in 2015 and also made it a part of its national development strategy. Nonetheless, all gender inequalities across the urban-rural split and socioeconomic class remain significant, and are expected to worsen as a result of Covid 19.

The paper argues that the ‘sparse rurality’ of Balochistan poses multiple challenges. There are around 3,974 schools for girls and 9,700 for boys. Given the scattered population of the province more funds are required to educate all the children, including girls. The paper suggests for alternative solutions of mobile schools or flexible schools in the rural areas.

Moreover, in the absence of certified teachers, pesh imams of local mosques frequently teach children. The local communities trust them due to their role in spiritual, social and community activities. In such circumstances, the paper advocates for imams to be mainstreamed, by training them in contemporary education.

Balochistan’s culture in fact facilitates and supports girls’ education. It accommodates female teachers and their families in school premises to ensure girls get education. The decisions are taken by village malik (elder), and governance of girls’ schools strengthens his authority in the area.

In this case, two advantages of application of conceptual framework of post-colonial Islamic governmentality are suggested: first, the participation of pesh imam improves girls' opportunities in rural areas to receive modern education as well as religious instruction; and second, it brings local religious actors, development organisations and public institutions closer, allowing for a productive relationship between religious and secular-modern forces.

The paper also discusses the challenges of lack of availability and low standard of public schools, which results in a growing tendency of girls’ enrollment in informal madrassahs. Around 3,200 of the province's numerous madrassahs are officially registered with the government. These madrassahs and/or mosques with pesh imams -- as teachers in locations where girls’ schools and female teachers are not available -- can become schools for girls up to levels primary level and beyond.

It highlights that social and gender relations in Balochistan are guided and understood by the discourse and practice of Balochi riwaj (traditions) in the province, whereby women/girls are thought to be honour and dignity of the family, clan and tribe. Islamic norms and practices interplaying with riwaj and shape girls’ schooling. The paper also shows that the intersection of local cultures and Islamic practices do not stop girls from going to school.

Balochistan’s culture in fact facilitates and supports girls’ education. It accommodates female teachers and their families in school premises to ensure girls get education. The decisions are taken by village malik (elder), and governance of girls’ schools strengthens his authority in the area.

This paper also provokes many questions: for example, what will be the mechanism of equating the qualification and skills of pesh imam to enable him to teach Science, IT and other courses in addition to spiritual? Will pesh imams stay in the same village if they are provided employment as teacher? How will malik find space in the education policy making? How will girls in primary education taught by imams pursue higher education? Girls may have to relocate to attend colleges and universities. In this sense, postcolonial Islamic governmentality as a theoretical approach can be applied at different junctures and locations to analyse girls’ education in the country.

The paper provides significant insights. It provides an academic understanding about the problem of girls’ schooling. It merits a thorough reading by the policymakers, scholars, academics, researchers, policy analysts and stakeholders to understand policy problems with regard to girls’ education in the country.

The writer is an undergrad student at Quaid-e-Azam University, Islamabad. He tweets at @amin_salal