I vividly remember that it was mid-April 2021. I was teaching an MSc Rural Development class at the city campus of NED University Karachi. The topic of the session was “Villages, Their Types and Regulating Authority.” I finished the class as per schedule, but before I left the podium, the class representative asked me to give them some clues on “how to write about an old building.” Upon my inquiry, I was told that the class had to visit the Shri Swami Narayan Mandir (Karachi) and afterwards write a visit report. I instantly excused myself, stating that I am not an architect, but that I could provide them with some outlines if the class was willing to spare their time without compromising regular classes. Initially, they agreed, but the session didn’t take place. I don’t remember the reason; my notebook is also blank about it. I saved the would-be session’s notes into my laptop and forgot it.

Yesterday, I received an email from a student of the Department of Sociology, University of Sindh, Jamshoro. Interestingly, the email’s text was related to buildings. I wrote back immediately, thanking him for the email that has inspired me to write a full-fledged article. I retrieved the long-ago saved note and reorganized its text to make it relevant to the key points raised in the email. Now, allow me to start my write-up.

I begin with a generic statement: before writing about any type of building—house, hotel, hospital, church, temple, and even mosque—some general background research is essential. This can start with reading secondary sources, then moving back to the present situation of the building. Switching between sources and observation or visit of the building will help the writer identify the gap—what is present before him/her and what is portrayed in books. In fact, that ‘difference’ is the magical area where writing about the building must take root.

Traditionally, there are three main types of sources for writing the history of a building: physical sources, secondary sources, and documentary sources. Some scholars consider documentary sources as part of secondary sources; however, the nature and type of the material demand that it could be treated separately.

Another common question is: what tools should a writer carry in the field while visiting the building? Presently, there are many gadgets to record and write notes, but I still appreciate the old tools for recording observations. Therefore, I always suggest using a notebook and carrying a good camera while you are in the field. However, an invaluable ability that we human beings have is our senses. In fact, out of five, the use of four senses helps to observe critically. For instance, ‘hearing’ an audible wind blowing in an old empty building gives an idea of air circulation and the direction of ventilation. Similarly, ‘seeing’ helps us to understand the building’s layout, damp floors and connectivity with the neighbourhood. Likewise, ‘touching’ provides insight into the materials used, while ‘smelling’ helps us note if the building has been closed for a long time or if its drainage system has stopped functioning. Thus, writing about a building should begin with sharp observation, using freely available tools such as vision, hearing, touch, and smell, followed by noting observations in the notebook and supporting them with photographs.

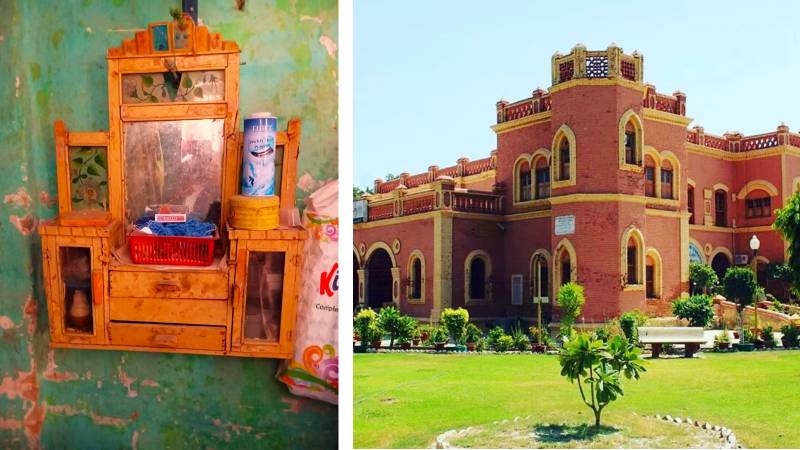

As I said earlier, the physical source is the building itself. Therefore, as a writer, one must note: what the building looks like now and what it looked like in old photos and drawings. If there are alterations, this indicates that physical changes have taken place. The researcher’s first task is to write about the background of these changes—listing the types of reasons. Has the owner made new additions or altered the size of rooms? Has a new association taken possession of the building and completely changed its old image? Other minor changes to observe and document include alterations in the colour of the building (explore the cause—environmental or anthropocentric); investigate why windows are permanently closed with bricks; and examine reasons for alterations in the roofline. Systematically, with a timeline, write down which parts of the building have been recently added or demolished, and find out reasons and documents in detail.

Another pertinent challenge writer face is determining the age of old buildings. There are practical clues: if the building exists close to the city centre, it is likely old, but the writer must find out its exact construction date. For instance, some old settlements of Hyderabad are located near Paka Qilla and Shahi Bazaar, indicating that the neighbourhoods of these two main areas are the older parts of the city. However, the type, size, and material of the bricks used in construction can provide clues about its age. It is suggested that the ground floor’s materials be used to assess the building’s age because some apparent parts might have been added in the recent past. Another common clue is the architectural features of the building, which help to determine the era in which a particular building was constructed. For instance, old buildings in colonial Sindh, particularly government buildings, missionary schools, and official bungalows, feature designs blending British architectural elements and Sindhi characteristics, such as domes, arches, and intricate carvings. Moreover, local materials like limestone and clay were used to suit the climate. Sometimes, examining the type of building and the size of the beams can also help estimate the building's date.

Most researchers tend to avoid using oral evidence in their writings: and so, an opportunity is missed to learn about the previous inhabitants or even the previous uses of the building. The aspiring historian must remember that buildings are not just a blend of mortar and bricks; they are static storytellers of our shared history and cultural evolution

Without a doubt, the building’s date on its foundation stone is the most authentic source for knowing its age. However, the researcher must ensure that the foundation stone’s year matches the apparent age of the building. This observation is relevant to Hyderabad’s houses, where, in many cases, new allotees have removed or rubbed the old ownership stone and fixed a new one in the same slot. In all situations, it is essential to check with other sources and gather data in light of these questions:

Is the building listed or protected as a heritage site?

Does it belong to evacuee trust property?

Is its custodian the Auqaf Religious Affairs, Zakat and Ushr Department?

An aspiring historian should not forget that every building – particularly so in the case of public buildings – has a long social history. Some scholars use the term ‘the past of the building,’ but the social history of a building is a much more comprehensive. For instance, when writing about the Annie Besant Hall (now the Besant Hall Cultural Centre), one must discuss the historical context of that era, the role of the Theosophical Society in Indian politics, the Home Rule Movement, and Dr Annie Besant’s political, social, and educational ideas. It is important to chronologically set the context of the events that took place at the premises of the Annie Besant Hall.

It is true that the names and uses of buildings often change over time. A notable example is Holmsted Hall in Hyderabad, originally constructed by the British Government in recognition of Dr Holmsted’s services. It later became the broadcasting station for Radio Pakistan and is now known as the Hasrat Mohani District Central Library. This case illustrates how both the name and purpose of a building was changed.

While Holmsted Hall is a single example, a more widespread illustration can be seen in the temples of Hyderabad. Prior to the 1947 Partition, these structures served as places of worship. However, after the Partition, many of these sacred sites were repurposed as residences. A diligent historian must highlight these changes, examining the shifts in name and function of the temples. It is essential to explore why and how the government at that time allocated worship places to migrants, transforming them into homes.

Regarding present usage of all buildings – public or private - an authentic source can be photographs. Suggested themes include close-ups of features of the building from different angles. Comparing these recent photos with earlier drawings, photographs, sketches and plans of the building helps the researcher to understand how the building’s usage has been changed. Unpacking this change process with a historical perspective will provide the historian with ample material to write about both the past and present usage of the building.

Most researchers tend to avoid using oral evidence in their writings. They are often disinterested in talking to previous owners or occupants of old buildings. If such an attitude persists, an opportunity is missed to learn about the previous inhabitants or even the previous uses of the building. A difficult challenge for the writer is to obtain authentic information about private buildings. However, one source that is generally ignored is property’s title deeds. In addition to deed documents or lease agreements, other areas to explore are city survey numbers, city maps and architectural drawings. But, writing about private buildings, one must keep in mind that private property changes hands—but they have stories to tell.

The aspiring historian must remember that buildings are not just a blend of mortar and bricks; they are static storytellers of our shared history and cultural evolution. Each structure carries the weight of time, echoing the lives lived within its walls and the dreams that once flourished in its shadow.

Yet, as we gaze upon these architectural relics, we confront a bittersweet truth: many are slowly fading, their stories at risk of being lost to the relentless march of time. Thus, it is our solemn duty to preserve and celebrate these irreplaceable gems, ensuring they endure to inspire future generations.