Indian archaeologist RD Banerji, Superintendent of the Archaeological Survey of India, Western Circle, excavated Mohenjo-Daro in December 1922. He continued excavating this site 27 km in the south of Larkana up to January, February and March 1923. Banerji compiled and submitted his excavation report entitled “Mohen-Jo-Daro: A Forgotten Report” to Sir John Marshall in the Office of the Director General Archaeological Survey of India, which was never published until 1984.

DR Bhandarkar had visited the Deserted Site of Mohenjo-Daro in March 1912.

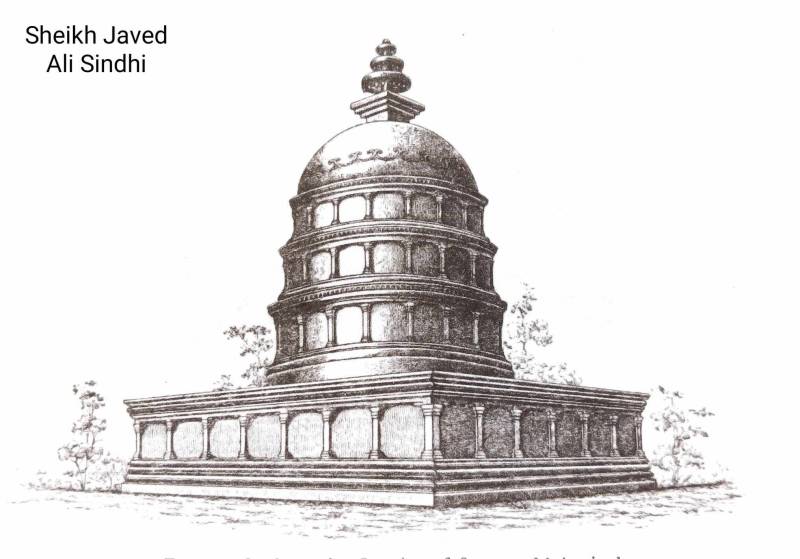

Describing the Buddhist Stupa of Mohenjo-Daro, RD Banerji writes in his report:

“My attention was drawn to the site on the occasion of my first visit to Mohenjodaro, on account of its mud or sun dried bricks, is visible for miles. The highest point of this tower is still 65 feet high from the ancient river bed and more than 70 feet in height from the cultivated area around the ruins. In December 1922 the excavation were begun at first in a small narrow valley between Site No. I & II which appear to have been originally a creek or inlet flowing between two islands. I looked for the last step or landing of the ground staircase which led up to the top of the building.

The villagers of the neighbourhood had unfortunately carried away all the bricks near the ground-level, and therefore I couldn’t find any trace of such a staircase. I turned my attention, then, to the top of Site No 1 or the space on the platform surrounding the stupa. At the time of my first visit in December 1919 only a small portion of mud tower was visible above the surrounding waste of bricks.” (Page 29)

The ground around Mohenjo-Daro was covered with low scrub, consisting of Babul (Acacia Arabica), Camel Thorns (Tamarisk Indica) and other wild plants. To the north of the Mohenjo-Daro ruins, there was a thick reserved forest on Lanyaro, a dried up bed of the River Indus. The Bagi Forest was in Gaji Dero forest block and it was first surveyed in 1887.

Who destroyed the Buddhist Stupa of Mohenjo-Daro?

The Pioneer Mail and Indian Weekly News, Allahabad-Bombay, India (dated 15 June 1923) published some details about “Excavations in Sindh: Interesting Finds, Discovery of Ancient Coins.” That publication noted that:

“In the centre of the first mound was a high stupa of sun dried bricks built on an oblong platform of burnt bricks. Surrounding this central structure there was a series of rooms on all four sides. The entrance to this shrine lies in the north eastern corner whence a broad sloping staircase leads down to the waterside. The structure which exists on the top of this mound was erected in the 2nd century A.D. during the reign of the great Kushan Emperor Vasudeva I. (158-177 A.D) many of whose coins have been discovered. The stupa of sun dried bricks was hollow and once contained a deposit of relics which had been ruthlessly destroyed by the Zamindars of the neighbouring villages who excavated the interior of the stupa a few decades ago with a view to finding buried treasure”. (Page 32)

Personally, I am of the opinion that as this Buddhist Stupa belonged to the Mahayana form of Buddhism, it was called, Mahayana Jo Daro, which means the mound or temple of Mahayana monks.

The Sind Official Gazette of 05 May 1910 calls it “The Deserted Site of Mohan Jo Daro”. People also called this mound as Mohen Ji Maari. And a mahri means a place where Monks or Sanyasi faqirs live.

How was clearing work at Mohenjo-Daro started? RD Banerji writes in his report:

“We began by clearing the area in the immediate vicinity of the mud tower or stupa. At the same time a second gang was employed in clearing the debris just below the eastern retaining wall of the high platform on which the stupa had been built. The excavation along the eastern retaining wall was productive of excellent results, as during the excavations, Mr N.S. Chikte who was in charge of the trench, made the momentous discovery of two seals with pictograms or ideograms of the same class which had been discovered up to date, only at Harappa in the Montgomery District of the Multan Division of the Punjab.” (Page 29)

Mohenjo-Daro’s ruins supplied building material to the state and locals

Providing details of the theft of bricks, Banerji writes in his report:

“Though the ruins of Mohenjo-Daro have supplied building materials to the state as well as to the private people of the locality for centuries past, the first retaining wall is still 25 feet in height from the present level of the river bed and the third 44 feet. The preservation of these walls for millennia is due, no doubt, to the excellence of its masonry and bricks. The depredations of the villagers in this area have deprived us of all means of reconstructing the plan of these older structures.” (Page 32)

He again writes regarding the eastern side of the stupa:

“At that time the slope of the mound was much gentler than what I saw in December 1922. It appeared to me at the later date that the neighbouring villagers had carted away a good deal of bricks from that side alone.” (Page 29)

Hunting for gold, silver and treasure by unknown people

RD Banerji heard many stories about treasure hunting at Mohenjo-Daro in 1922. He writes:

“The villagers have excavated the centre of the solid platform up to the depth of 14 feet and some of them informed at the time of the visit of Mr J. L. Rieu, ICS, then Commissioner of Sindh, that some unknown people had excavated the centre of the platform in search of Gold, but they had failed to find anything except certain pots made of marble. These marble pots were the relic caskets in which the bones of Buddha or some local Buddhist saints might have deposited inside the hollow chaitya.

The treasure-seeker broke the relic casket and threw the fragments away into the courtyard. Some pieces of these relic caskets were recovered during our excavations, but as all fragments could not be recovered, they cannot be restored or repaired. One of the marble relic caskets was an ordinary bowl with a lid of the same material. The second one was shaped like a round casket, very small in size, and this was most probably covered with a lid made of conch-shell. Most probably there were other caskets made of precious metals like Silver and Gold, but there seem to have taken away and melted by the treasure-seekers.” (Page 42 & 43)

The stupa and the surrounding ground were full of saltpetre or some other salt which was carried away by villagers and sold as manure in nearby markets.

Describing the seven-feet-thick layer of ashes belonging to the earlier stupa at Mohenjo-Daro, RD Banerji writes:

“The space between the grand staircase and rooms No.1 to 3 is occupied by a deep pit or a room, which when excavated yielded tons of ashes mixed with moulds of lime, fragments of bones and charcoal. The entire amount of ashes excavated from this room alone, could not have been less than 5 to 6 tons. Rooms No. 1, 2 and partly 3 of the quadrangle were built right over this heap of ashes. Just at the north eastern corner of Room No.2 there are 5 different strata of ashes under the lowest buildings in that room.”

(Page 76)

“The lowermost pavements in Room No. 30 and 32 must therefore be earlier in date than the 3rd century BC. This level is slightly lower than the find spot of a large number of square die struck coins buried in a pot and found in Room No. 34.” (Page 38)

According to RD Banerji, there was a pre-historic Ziggurat, 100 feet high from the surrounding ground level, on which the Buddhist Stupa of Mohenjo-Daro was built. He writes as under “Under the platform of the stupa there is a layer of canes showing that some time in the 1st century A.D. an older shrine was burnt down, most probably by the Scythian invaders of India who occupied the North-Western frontier for nearly two centuries about the time of the birth of Christ. This shrine of the 1st century A.D. was decorated with bas relief in stucco, fragments of which have been recovered from sand beds in front of the shrine. One of these stucco heads represents a barbarian with a short-pointed beard and a long conical cap.” (See: The Pioneer Mail and Indian Weekly News, Allahabad-Bombay, India, dated 15 June 1923, Page 32)

Later on, RD Banerji wrote an article entitled “Mohenjodaro: An Indian City 5,000 years ago” which was published in The Calcutta Municipal Gazette, dated 17 November 1928. He writes,

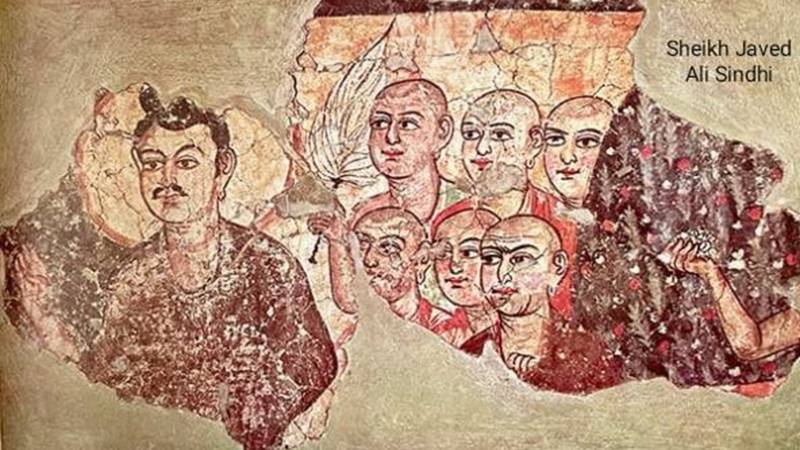

“So, in the first century, B.C, a Buddhist Stupa was built on the top of the ruins of what was, perhaps, the sanctuary of the sacred snake, and above it there was a later stupa of sun-burnt bricks decorated with fresco-paintings fragments of which I discovered in 1922-23, and brought to the Indian Museum, Calcutta, under instructions from Sir John Marshall.” (Page 95)

About the date of the mud drum (diameter 33 feet) of the Mohenjo-Daro Stupa, Banerji writes:

“The date of the mud drum of this stupa and therefore of the deposits of the relics in it, can be determined from the fact that the Kharoshthi characters found in the painted frescoes correspond to the form of the alphabet to be found in the Sue Vihar Copper Plate of Kanishka-I. This date agrees with that of the coins found in the topmost layers. Or pavements of the rooms on the western side of the quadrangle. In these rooms as well as the Room No.1 and 2 of the Site No.2 the Siva and Bull type copper coins of Vasudeva-I were found in the undisturbed upper layer.” (Page 41, 42 & 43)

This drum was a part of rectangular terrace of baked bricks or “a high artificial tower”. It was also called a stepped platform which had a small porch on its eastern side. Regarding original design of Mohenjo-Daro Stupa, Sir John Marshall thought that this stupa resembled with its contemporary monuments like Thul Mir Rukan, Kahu Jo Daro, and Taxila (See: Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Valley Civilization, Vol: 1, 1931, Page 116).

According to RD Banerji, this was the largest and highest stupa in the land of Sindh. He believed that fragments of fresco paintings were similar to those discussed by Sir Aurel Stein at Khotan, in Xinjiang, China. This Buddhist Monastery was a great centre of Mahayana studies in the 3rd century AD. It seems that there were social, cultural, economic and religious linkages between Kingdom of Sindh and Khotan in that era.

When Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang visited Sin Tu (Sindh) in 640 AD, he saw several hundred Sangharamas, occupied by about 10,000 priests. They studied the Hinayana or Little Vehicle according to the Sammatiya School. According to him, when Tathagatha was in the world, he frequently passed through this country; therefore Asoka had founded several tens of Stupas in places where the sacred traces of presence were found. Upagupta (3rd Century BC), the great Arahat, and spiritual teacher of Mauryan King Ashoka sojourned very frequently in the Kingdom of Sindh, explaining the law and convincing and guiding men. The places where he stopped and the traces he left were all commemorated by the building of Sangharamas or the erection of Stupas. Most probably The Buddhist Stupa & Monastery of Mohenjo-Daro were deserted at that time. Mahayana Sect encouraged Idol worship while Hinayana stressed individual salvation through self-discipline and meditation.

Greek geographer Claudius Ptolemy (b 100 AD – d 170 AD) mentioned Piska, a town of Indo Scythia on the River Indus in his map of the World/South Asia, prepared by him in 150 AD (See: Ptol.7.1.58). M U Erdosy (1997) has given both names Piska and Pardabathra in his Map 6 Asia Orientalis. Pardabathra was its neighbouring town in the west. MH Panhwar believes Piska was Mohenjo-Daro. (See: An Illustrated Historical Atlas of Soomra Kingdom of Sindh, 2003, Page 40)

Personally, I identify Pardabathra as Badeh Bothra, a historic town situated 10 km in the west of Mohenjo-Daro Archaeological Site. Close to Badeh City there are ruins of Dhamraho Jo Daro, a Buddhist stupa and monastery dating back to 400 AD. I have identified Piska with Portiska (Portica) or Porticanus, a King or Prince of Oxycanus or Upper Sindh whose country formed an Island of River Indus called Prasiane. After conquering the Kingdom of Musicanus (Sukkur/Rohri), Alexander the Great came to the country of Porticanus (Larkana) in 325 BC. Porticanus, who had fled for shelter into the Castle, was killed fighting in his own defence.

Discovery of Greek Coins from Mohenjo-Daro

RD Banerji, writes that:

“The western side of the platform is covered with in the uppermost levels of the rooms of the quadrangle. The fact that the hollow Chaitya was not built exactly in the centre of the solid oblong platform of burnt brick, proves that platform itself cannot be contemporary with the hollow stupa. While excavating the slope on the southern side of this platform a large quantity of ashes were discovered in the crevices of the masonry of burnt bricks proving that the original structure on this platform was burnt down and the hollow Chaitya of sun dried bricks was built in the place at some later date.

The platform of burnt bricks has, attached to it on its eastern side, a shrine with staircase for going up to the base of the stupa and a porch in front in the style of the Gandhara Stupas of the 1st Century B.C and AD. The discovery of a solitary but unique Greek coin in this area leads us to suppose that this structure was built in that period.” (Page 35)

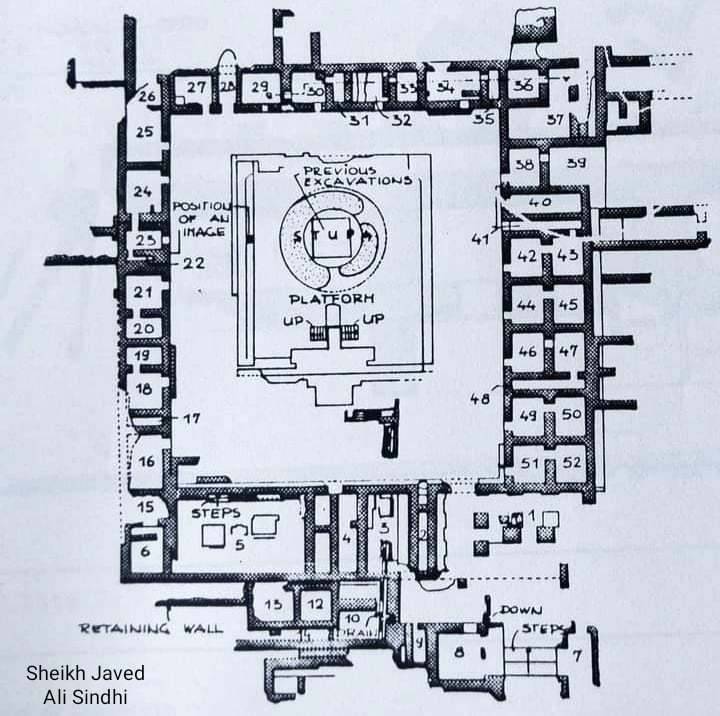

Quadrangle of Rooms, Buddhist Monks’ Cells and Chapel

The Plan of Excavations Mohenjo-Daro: Site No 1 (Stupa Area), 1922 & 1923 shows that Banerji had cleared a total of 52 large and small rooms or structures from the four sides of the Buddhist Stupa and Monastery. This plan was published by Dr Michael Jansen in the preliminary results of three years of documentation in Mohenjo-Daro, 1983. The number of excavated rooms around the Buddhist Complex reached 65 after Sir John Marshall’s excavations carried out between the years 1925-27 (See: Sir John Marshall, Vol 3, and Plate XVI). The cells on the north side are double, and correspond to a well-known type in northern India, for example from Nalanda and Taxila.

An inner room served for sleeping and the other one for living. The sundried bricks and sand had been spread over the floors for facing summer temperature. The chapel, built with mud and plaster, was in the north of stupa.

Up to the end of the 3rd century, if not later, it was unusual to have kitchens, pantries, and the like attached to monasteries. Before that the monks seem to have begged and eaten their food in the towns, or to have prepared it, each for himself, in his own cell. It was not until conditions became more luxurious that common kitchens, storerooms, and amenities were provided, and the monks thus enabled to devote more time to their religious and literary activities. Sir John Marshall believed that the Buddhist Stupa of Mohenjo-Daro had kitchens, pantries and storage rooms (27a, 29a, 30a) on the west. As far as my own research is concerned, around 100 to 150 Buddhist monks lived inside this monastery.

Under a high priest, they learnt about Buddha’s life and performed rituals with texts. There was a customary ritual to clean stupa before first worship daily. The monks used a small bath in the south east of stupa beside refectory. Perhaps they went to banks of River Indus for ablutions. It is thought that they used makeshift toilets in the ruinous portion in the jungle. They lighted oil lamps at night and used red sandstone slabs as seats.

RD Banerji ended his excavations on 30 March 1923. He discovered seals, carved bricks, relic caskets, lids of vessels, stucco pieces, faience, bone, metal, stone and shell objects.

The courtyard had an entrance; shrine, hall of assembly, refectory (dining room) and bath from the east. The entrance to this shrine was situated in the north eastern corner whence a broad sloping staircase led down to the Riverside. Most probably the sides of staircase were covered with long trees, plants and wild bushes. Mr RDBanerji found broken pieces of Fresco Painting plaster from the neighbourhood of this stair. He wrote, “The only opening lies through a pillared hall in the north eastern corner and not through the middle or any of its sides. Outside the pillared hall began a grand staircase with broad landings”. Another doorway was from the western side of stupa.

There was a wooden verandah which protected pilgrims from the sun’s scorching beams, monsoon rains and winter severe cold. The stupa had two doorways, one from east while another from western side. The pieces of coal are still found around the stupa area.

Banerji reported about the eastern and southern Retaining Walls at the Stupa Area in Mohenjo-Daro.

He writes, “Like the architects of Babylon, ancient architects of Sindh in the earlier centuries, before and after Christ, built their religious shrines on the top of huge artificial platforms protected by retaining walls 40 to 50 feet in height in order to save them from the high floods to which a flat country like Sindh was subject. Mr Banerji excavated two more mounds containing the ruins of religious establishments or shrines built on islands in the ancient bed of River Indus. These 3 mounds were built in the 2nd century A.D. and consisted of high Buddhist Stupas”. (See: The Pioneer Mail and Indian Weekly News, Allahabad-Bombay, India, dated 15 June 1923, Page 32)

The western Retaining Wall was excavated by Mackay from 1927 to 1931 in the Divinity Street. These strong Retaining Walls had buttresses to support them from falling down.

Banerji believed that these walls belonged were not contemporary to Buddhist Stupa but were of much earlier period. Mr N.S. Chikte discovered two seals bearing figures of bulls – one entire and other broken in some structures which lay at the foot of the exterior retaining wall on the eastern face of the main general platform.

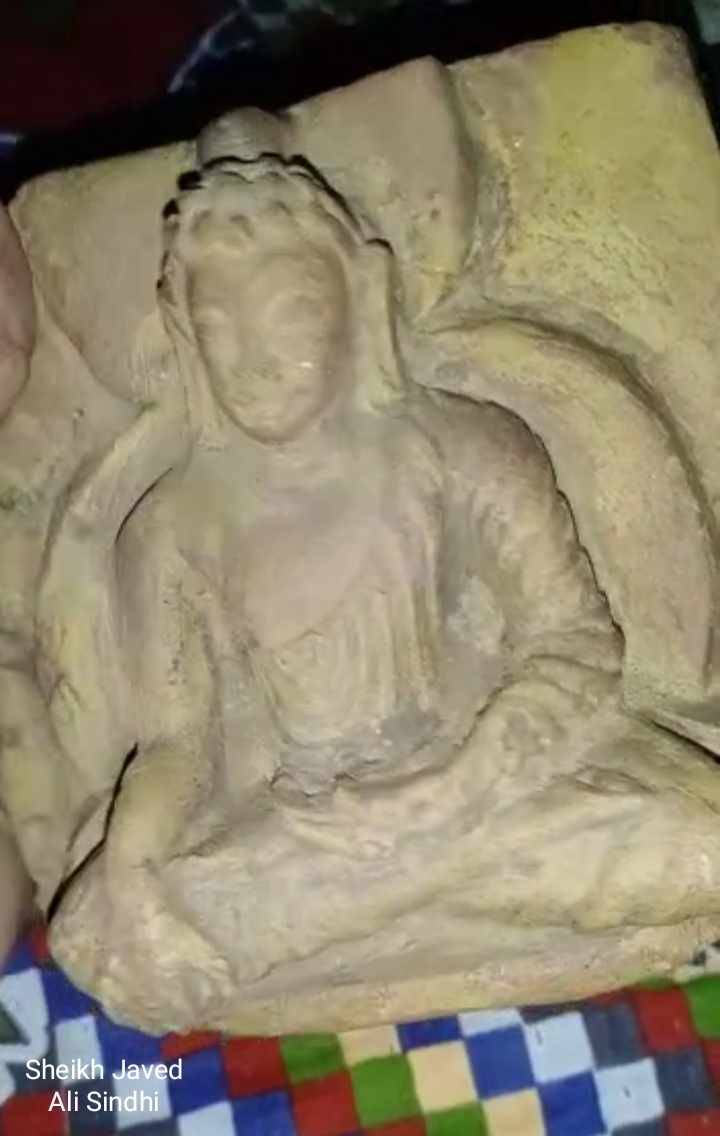

Regarding the discovery of Buddha’s Statue from Mohenjo-Daro, Banerji writes that:

“The eastern face of the platform of this stupa was the most elaborate, and contained a large niche with an image of Buddha, after the fashion of the Indo Greeks stupas of the North Western Frontier. “As the big stupa in Site No.1 is not far distant in date from the Indo Greek stupas of Afghanistan and North Western Frontier Provinces it is not surprising to find a similar niche with an image of Buddha in this structure. This niche or shrine occupies exactly the centre of the eastern façade of the platform, and consists of a porch in front, a passage running westward at right-angles to the porch, a staircase on each side of the passage and a narrow room with a higher floor at the western end of the passage. This niche is 7 feet in length and 4 feet in breadth. In the western wall of this recess there was an image of Buddha seated cross-legged, most probably on a lotus (throne).

The core of this image consisted of bricks placed in different positions and the positions of the knees of the main figure are still indicated by bricks which hold the coating of mud and which no doubt was painted and gilt. The position of the hollow, the head and shoulders can still be seen in outline against the mud and brick masonry of the back wall of this niche.” (Page 44)

Some Buddhist images of stucco were also discovered in 1922. Banerji writes that,

“The adjoining room on the south, No.3 is more interesting on account of the fragments of Buddhist images of stucco discovered there by Mr N.A. Wartekar… While clearing this area Mr N.A. Wartekar suddenly came across a circular piece of plaster with deep mouldings, the depths of which were touched with black. Subsequently 8 more pieces of stucco were brought to light. They formed parts of a loosely draped standing figure of Buddha in which the upper robe, (nanghall) was depicted in the peculiar manner characteristics of the northern or Gandharan School of Art.” (Page 52)

“They resemble similar pieces discovered by Sir Aurel Stein in different parts of Central Asia. The pieces recovered represent fragments of drapery only. No head, no leg or arm was found. When the entire mass of sand was shifted, only one fragment looks like a spindle-whorl was discovered which may have been the top-knot (chuda) of a Buddhist image. The stucco images were most probably destroyed during one of the river conflagration which destroyed this religious establishment at different periods. These fragments of stucco are painted with alternate bands of red and black and the colours are very bright even now. In addition to these stucco fragments we discovered the torso of a clay image of Bodhisattva made of fine alluvial clay with a red necklace or garland round his neck”. (Page 53)

This clay image of Buddha was found from the southern side of Stupa. Some of the bas relief stucco fragments had been recovered by Banerji from sand beds in front of the shrine.

Banerji writes about stairs leading to the northern and southern side:

“In front of the niche there is a narrow passage 7X4 feet, the flour level of which is 4 feet below that of the niche. From this passage two staircases, mentioned above; go up, one to the north and the other to the south. 6 or 7 steps of each of them were discovered undamaged. The purpose of these staircases is difficult to determine at the present date. It may be possible that they were used by later worshippers at the Buddhist Shrines, for going up to the base of the stupa and performing the circumambulation (Pradakshina) which forms a part of Buddhist, Hindu and Jain worship. But it is also possible that these steps were used by the priests of monks in charge of the shrine to reach the head of the image in the niche. These steps are exactly similar to those which are still to be seen in Jain temples at Khajuraho and Uri. The upper part of the niche was discovered in a damaged condition and it is not possible to determine, now, whether it was originally covered or not.” (Page 45)

Fragments of Relic Caskets, Vessels and Lids

According to Banerji’s Report on Mohenjo-Daro,

“While clearing the eastern portion of the quadrangle certain objects of stone were found at different places. In the north eastern corner a large slab of red sandstone measuring 2 feet in breadth was discovered. The exact length of the original objects cannot be determined as the ends are missing. Besides these fragments, the legs of these two different seats, also made of similar reddish sandstone, came to light. Two fragments of two different lids of vessels or relic caskets were also discovered at the same place. They are too fragmentary to admit of measurement; but one of them appears to resemble the upper part of a lotus petal and is double convex in form. The top of this fragment is polished. The upper part of the second fragment is also tapering in shape towards the end like a lotus petal, but there is no convex surface inside. Another round lid of a vessel made coarse marble or sandstone was also discovered in this area” (Page 46)

On another mound on the same island (Site No. 2) Banerji discovered another platform containing the ruins of another stupa(s), inside which were found nearly 200 relic caskets of marble, all of which had been broken to pieces by treasure seekers. The excavation of this site was undertaken, mainly, to find out the causes of the subsidence of this mound. Large tunnels, high enough to admit of a man’s passage were visible at the north eastern corner of this mound, which has fortunately been photographed in December 1919.

The local people took these tunnels to be the lairs of wild animal especially wolves called Baghghads (Wolves) in Sindhi who bored holes in such remote and secluded places. But during excavation it was found out that the tunnel had been excavated by treasure-seekers and was 6 feet in height, 6 feet in width and about 100 feet in length. A man could easily walk through the tunnel and entering it through the hole in the eastern face of the mound pass out through what subsequently proved to be a bay or shrine, No 23, in the western façade of the main shrine to the north eastern part of the site. (Page 81)

At different places, small glazed bricks neatly laid in the pavement were discovered during 1922.

Giving details about the small votive stupas at Mohenjo-Daro, Banerji writes:

“Numerous small platforms came to light on the eastern side of the platform. These probably represent the remains of small Votive Stupas built around the main stupa. Unfortunately none of them has survived in a complete state like the stupas discovered by Dr. DR Bhandarkar at Mirpur Khas in 1916-17” (Page 40) Mackay (1938), excavated 5 large brick circular constructions in the north of Great Bath in Block 8 SD Area . He claimed that these were the foundations of small Votive Stupas. Currently these stupas have been disappeared from the ground (Mosher: 2017, Page 300)

A Child’s Grave/Cist (Room No 27)

Explaining a new kind of burial, Banerji writes:

“Room No. 27 must have been a shrine of great importance and regarded with exceptional reverence. Its walls were plastered with fine mud and painted white and red. Two different systems of burials were discovered in this room. One of them consists of a brick cist containing the body of a young girl. The cist or tomb was built of bricks and a layer of debris and the wall consisted of a single bricks, while the covering was provided by bricks of the same size laid lengthwise. On account of the brick covering, it was at first taken to be a drain but on removing the covering the cavity was found to be filled with dry sand which had preserved the dead body almost entirely.

The bust and the hair of the head were in a fine state of preservation through shrunk, but the nose and eyes had disappeared, and the skull had rolled outside and was found on the lower pavement of the room. The bottom of the cist is 2.4’ above the lowest course of the bricks of the platform in centre of the courtyard on which the stupa had been built in later days.

Before the camera could be brought up the torso crumbled to dust though muscles and flesh can still be seen adhering to the bones in the photograph. The eastern wall of this room (27) which bears on it the brick cist containing the dead body of the young girl may belong to the 2nd century BC, but it is certain that the brick cist belongs to an older structure which was not demolished when Room No 27 of the 2nd century AD was constructed.” (Page 120)

Pataliputra was an ancient city built by Magadha Ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BC. It also became a capital of Mauryan Empire. Describing a polished black vessel, Banerji writes that,

“The most peculiar finds in this burial jar were 10 fragments of a highly polished black vessel, which appears to have been pieced together before its deposit. The different pieces were found together by means of little hole bored in many of them. The texture and the polish of these black fragments resemble the similar pottery discovered by Rai Saheb Monoranjan Ghosh, M.A, Curator of the Patna Museum during the excavations of Pataliputra”. (Page 63)

“A fragmentary of a round marble relic casket, a toy jar, a horse made of terracotta and a round copper coin were discovered here” (Page 65)

“A round lid of some vessel possibly a relic casket, made of conch shell was discovered in this room”. (42) “The size and make of this lid is exactly similar to that discovered in shrine No 22 on the south; the only difference being that instead of a hole in the centre, this one is fitted with a copper ring attached to the hole”. (C.221) (Page 73)

According to Banerji, NA Wartekar, Head Draftsman of the Western Circle, discovered a number of fragments of frescoes with painted Kharoshthi and Brahmi inscriptions (2nd century AD), from the slope of the platform on the northern side of the stupa.

“This stupa was once decorated with fresco paintings in the manner of similar stupas discovered by Sir Aurel Stein at many places in Central Asia. Fragments of these fresco paintings show the use of indigenous Indian colour. In spite of exposure to the sun and rain of nearly 17 centuries, the colour are remarkably well preserved. Those fragments show the use of deep blue as a background and deep indigo instead of real black. Floral decorations in white on a blue ground or in yellow on a ground of chocolate and Buddhist mythological fragments showing the use of green, blue, yellow, red, white, and black have been recovered from the ruins”. (The Pioneer Mail and Indian Weekly News, Allahabad-Bombay, India, 15 June 1923, Page 32)

Banerji had brought fresco painting fragments to the Indian Museum Calcutta, under instructions from Sir John Marshall. Many of these antiquities were lent by the Director General Archaeology in India for exhibition held at Simla in September 1927.

Many Brahmi and Kharoshthi inscriptions were also found. Mr RDBanerji writes that,

“These frescoes are in an excellent condition in spite of their fragmentary nature. Despite the long exposure they have preserved their colours wonderfully, and their age can be determined by the forms of the characters of their painted inscriptions, both in Kharoshthi and in Brahmi. Same letters were discovered by Sir Aurel Stein in Central Asia. We find the word Samana written in Kharoshthi on one fragment. The word Samana is equivalent to Sanskrit Sramana and most probably to form part of the Buddhist creed. It means “a person who labours, toils or exerts themselves for some higher or religious purpose” or “Seeker, one who performs acts of austerity, ascetic”. Mackay and NG Majumdar also found some inscriptions from Buddhist Stupa of Mohenjo-Daro. Shaman is a local popular Sindhi name.

Discovery of Kushan Copper Coins

Banerji, describing copper coins writes:

“These copper coins are of the Siva and Bull type of the Great Kushan Emperor Vasudeva-I. It may therefore be taken for granted that the hollow Chaitya of sun dried bricks was erected on the platform of burnt bricks sometimes in the 2nd century AD. If we take this date as our starting point in the determination of the different strata discovered in Site No.1, then we must admit that all structures lying below the hollow Chaitya are anterior to the 2nd century A.D in date.”

According to NG Majumdar, Banerji discovered 2,170 copper coins from the Buddhist Stupa of Mohenjo-Daro. Sir John Marshall (1926-28) unearthed a hoard of about 1,100 copper coins. Ernest JH Mackay found a hoard of 1,078 coins between 1927 to 1931.

Recently on 15 November 2023, a hoard of Kushan copper coins weighing 5.5 kg was found from the Buddhist Stupa of Mohenjo-Daro during conservation work led by the Directorate of Archaeology Sindh.