Note: This extract is from the author’s coming autobiography titled Not The Whole Truth: My Life and Times.

Click here for the fifth part

In the summer of 1983, I got a bursary to travel to the United States to read the manuscripts of the novels of E.M. Forster. While most of the manuscripts were at Cambridge where I had read them, some had been bought by the Humanities Research Centre at the University of Texas at Austin. Luckily, I was in correspondence with two young men – Randolph and David – who had approached me to contribute an article on ephebophilia (a word I had invented for boy-love as in Greece and certain Oriental societies) in the Urdu ghazal. They were a gay couple and they actually kept a room vacant for me though they could rent it out and tell me to find accommodation. This way they lost money but they were very decent people. I did not, however, know all this before I visited them but I was happy that I would have a room without looking for one.

I flew by Arrow Air, a cheap airline which operated like a bus, and landed at JFK airport at midnight. Just leaving the airport itself was something of an ordeal and then I was told that the flight to Houston would be from New Jersey. The city of New York glittered with lights as we sped through it, reaching New Jersey airport only to find it closed for the night. Other passengers went to spend the night in hotels but I could not afford to do so. Thus, I had to wait for the morning in a lounge which looked deserted and dangerous since a few people prowled menacingly around it. In the morning, I caught the Houston flight landing in a city where the skyscrapers dwarfed me as I walked by them to catch the Greyhound bus to Austin. The big business signs and huge roads, the vastness of the land itself, gave me the feeling that I was in the land of plenty –- the new world. At Austin David (called Dave by everybody) stood smiling in warm welcome just outside the bus station near his Volkswagen beetle in which he took me home. Both Randolph (called Randy) and Dave were very nice people and I liked them. They were decent, generous and very friendly throughout though they did have some rowdy friends who alarmed me the first night but never appeared later. I understood that people like them were persecuted only for their sexual orientation and knew how callous, insensitive and prejudiced people could be. However, at that time they themselves lived quietly and happily as they said. Their friends, whom I met at lunch, were sober, intelligent and very decent. I even met the family of Randy. In fact, right on the day of my visit when I was tired and had not slept the night before, they took me to visit Randy’s mother in San Antonio and showed me all the sights of Austin. But in those days, I had so much energy that I enjoyed the trip and admired Randy’s kind-looking mother who gave me tea and homemade cookies. From the very next day, my routine was that I worked in mornings in the Humanities Research Centre and talked about most things under the sun with them in the evening. Thus passed a most interesting fortnight. After it I caught the Greyhound and Dave waved me off.

I was bound for Kansas City where my cousins Arshad and Shahida lived. Pervez Shams was also living nearby. After a long journey – I forget just how long – I reached Kansas City at night. Arshad Bhai was there to take me home. They had a nice house with a large backyard which I liked very much. Their son, Taimur, was a cry-baby of three or four and Shahida was expecting another baby soon. This baby grew up to be Sameera, a beautiful child whom we watched grow into a graceful young lady who took up medicine as a profession. Arshad Bhai tried to impress upon me the virtues of America while I pointed out the inequities of aggressive capitalism, lack of adequate healthcare, lack of safe and reliable public transportation and criticised America’s foreign policy. Thus, we kept having loud arguments all the time but I enjoyed them and I liked my visit. Pervez also came and showed me his house. He was still obsessed with power which, in his case, meant showing off about being in the police. He was as immature as ever but he was fun too and I liked him.

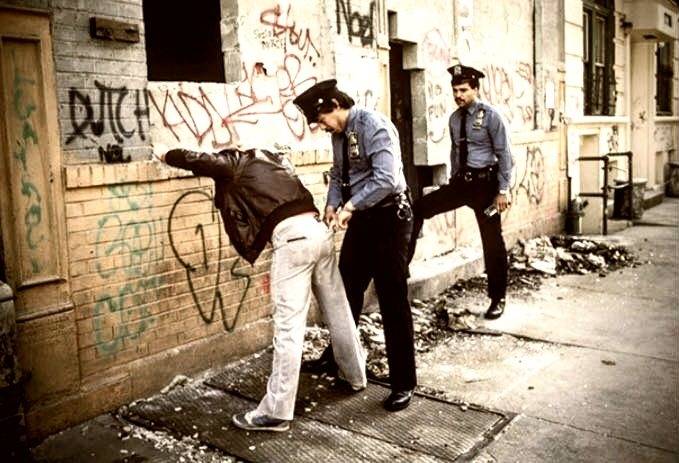

As my ex-student Afsheen had invited me to meet her family in Chicago, I took the Greyhound to that city at the end of my visit. As the bus neared Chicago, I saw the most glorious sunset of my life. For a very long time the sky was flaming red and the sun stood stationary like a huge ball of bright, luminous, enhanced red colour. The scene was awe inspiring in its majesty. But when I reached Chicago city centre (or downtown as they call it in America) it was dark and late at night. I could hardly afford a taxi so I started walking towards the underground station. I had been warned against crime in that area so I was alarmed but I could do nothing about it. It was, indeed, a frightening experience as I saw huge, fierce looking men lounging in corners. I also saw people looking for food in a drum of rubbish. It was a depressing scene. I was glad to reach the subway but that too seemed to be full of desperate characters. Anyway, there was no choice but to buy the ticket for the station Afsheen’s parents, the Afzals, had told me earlier on the phone. It turned out to be fifty miles away but when it did arrive, I was happy to see them waiting for me with a huge jalopy which must have seen better days. Afsheen and Sohail were really happy to see me and Farrukh seemed as worried and unsettled as ever. The parents had not found permanent work but they were very optimistic. I talked till the early hours of the morning and only a few hours later, I left by bus for Pittsburgh.

After a long journey over lovely countryside where I once had delicious ice cream, I reached Pittsburgh where I was received by Shaukat Bhai. I had seen him a long time back when he accompanied Khurshida Baji during his summer holidays to PMA. However, we recognized each other and he took me to his apartment. He cooked delicious chicken which we had for dinner. He also showed me the Carnegie-Mellon University and other memorable sights. Next morning, I wrote a letter of twenty pages outlining my views about American policies and the kind of aggressive no-holds-barred capitalism prevalent in the USA to Arshad Bhai and posted it. Only then did I leave for New York.

New York downtown was every bit as rough and dangerous as Chicago. There were booths showing violent pornographic movies – the kind which appalled me – all around me. I believe I must have been somewhere near Times Square but I am not sure. Anyway, I walked around to pass the time and, though hungry, I could not afford a decent meal. At last, I decided to watch some movies since they were very affordable even for me. Unfortunately, the first few moves I watched were not at all the risqué stuff at Soho or Berlin, they were real pornography at its worst: terrible, nauseating, dehumanizing and misogynistic and they were horribly violent—not my cup of tea at all! They could traumatize a person and I am sure such products cause much harm. I had already written in my paper on Lawrence that violence on TV and films should be banned and it exists to make money for the super-capitalists

I was, and still am, sure that violence of all kinds promotes violent behaviour, or trauma, among the viewers. And if it about sexual behaviour, men may treat women with the kind of violence they watch on the screen. My friends in England contested this view which they thought was the essence of freedom of expression but I thought this freedom, while necessary, should have limits when it comes to harming people. But returning to that afternoon in New York, after this bad experience, I did not watch any kind of movies since all American movies, from their posters at least, appeared violent and were in the kind of American slurred or drawled English I do not pretend to understand. In the end I confined myself to just walking around doing nothing. At last, after hours of walking, I caught the subway for the airport. Here Arrow Air let us down by announcing that they would be late. My hunger was now really so acute as to be distressing. However, they gave us meal coupons for the cheapest fast food available. This was a boon but what was one to do all evening and night? At last, we were boarded into the plane where people sat even on the floor until we took off at 2 a.m. It was a sunny morning in London when we finally landed and by the time I reached Sheffield it was a lovely, summer evening. Tania was charmed by the toy I had brought her and for Hana there were the usual chocolates. My first visit to America had been successful and I was so glad to be home.

As for visiting Paris, it was planned when Hana’s brother Naseem sent her some money. It was 500 pounds, so we planned a trip immediately. That day, however, I drove to look at some research material to the library of the University of Leeds library. When returning I had very little petrol in my car and I missed the exit to Sheffield. So, I did a foolhardy thing since I tried to cross over to the other side from a gap which for some reason someone had been left open on the motorway. And right then a car came and crashed with mine and its door got crushed. The owner was in a terrible rage and I had no papers at all. All I could do was to give him my phone number and the car’s registration number. Next day he rang me saying the repair would cost 500 pounds so the whole amount went to him. But Hana thanked God that I escaped unhurt and even the car was fine. The immediate problem which loomed over us was that I did not have a proper driving licence. There was a piece of paper I did carry but it was a military driving licence issued by regiments to military drivers. Even this has to be properly ratified by competent authority but mine was only an ad hoc thing signed by the adjutant—who, as it happened, was none other than yours truly at that time. It was, in short, not the sort of thing anybody would accept as a Pakistani licence. In Pakistan, with the inordinate clout of the army, it served me well but here it would land me in the clink. Hearing this, Hana immediately rang her uncle Feroz Mamoon, who was a government officer, to get me a government driving licence which he did. I hate such devious methods as does she, but at that time it was the only thing which could save me from very serious consequences so we had to resort to such underhand practices. Again, I promised not to take such foolish risks as driving without a proper licence.

After seeing my two documents he wrote on one: “Don’t change a word.” Then he said he would “throw me to the lions.” These lions, it turned out, were two famous professors of English literature. He himself, true to British fashion at that time, would not even be there when the lions ate me up

After this aborted plan of visiting Paris came the actual visit. This happened in the summer of 1984 when I and Hana had saved enough for a holiday package just for this purpose. We went by ferry across the Channel and then by bus. They put us in a small hotel which was in the Latin Quarter. After our continental breakfast we spent all our time walking all over Paris with Tania pushing her pram or trying to walk on her own. She had just learned how to walk and she would not brook being pushed about in the pram. Once she slipped out of her mother’s arm and ran across the road. And a huge bus just screeched the brakes and stopped as this small, hardly visible little doll scampered ahead of her distracted mother who ran after her. I too jumped ahead and caught her and pulled her back while I heard Hana shriek. Hana says people clapped but I have no memory of it. We should really have thanked the bus driver but we just stood petrified with beating hearts. We really had a fright and after that we became even more careful about the independent little mademoiselle who almost gave us the slip.

Paris was fun and we saw all the sights and loved them. Our lunch would consist of a peach – a luscious, juicy peach the like of which I never ate anywhere else. The dinner was always at Champs Elysees in one of the many cafes on that famous avenue. I liked French cuisine though Hana was more appreciative of the ice cream even there. At the end of the three days, we went to the coach stand but, having misunderstood the announcement, we missed the bus. This left us stranded in Paris for another day with very little money. As we sat in garden near the bus stop, a Pakistani youth came and greeted us. He told us about all the crooked things the Pakistani illegal immigrants – of which he was one – did to stay and work in France. I was disgusted to find out how such people let us down by lying and cheating so much. Much later I sympathised with them because economic pressures made them so amoral. Besides, it was really the amorality (or immorality) of the rich – rich countries and rich people – which made the poor so devious. And, in any case, where was my own ethics when I drove without a proper driving licence? Who was I to cast the first stone on this poor youth who did not have a privileged place in society? Now I think of it and feel ashamed of my attitude towards him. However, at that time I did not even appreciate the fact that the young man bought us biscuits and gave us his company. We got the next bus to the ferry and so came back to rainy Sheffield.

By the October of 1984 I was writing my PhD thesis. Besides working in Cambridge which I have already mentioned, I also went to the libraries in Manchester, Sheffield and London where I saw material which I used to write a number of research articles. Indeed, I got about five articles published in indexed journals before I submitted my thesis. My attitude towards publishing was not to go for journals which I thought would be very stringent in their approach. Thus, I published in Japan, India, France and the UK. However, at least two of the journals I somehow hit upon turned out to be highly regarded. Dr Mackerness told me that he had an article accepted in a journal in which one of mine had already been accepted. In those days doctoral students generally did not publish research articles before graduating. I did so not because of such a prudent thing as an eye to a future in academia but simply because it was in extension of my argumentative nature. Now I was, so to speak, having an argument with scholars in the reified atmosphere of academic journals. I had always this sneaking desire to be a scientist or a scholar and I relished the chance of publishing. Many of my literary theories and arguments, however, were not only against the British literary establishment (or so I was told) but also against what I thought were my own supervisor Heywood’s sacred cows. Of course, as was the fashion and my inclination, I published alone and did not have—nor did I ever have—any co-authors. In those days, except for science students, nobody wrote articles with supervisors. Indeed, in my subject it would have been considered absolutely immoral to do so. Thus, I published my work under my name and Heywood read my papers, if he read them at all, only after they were published.

By November 1984, I thought I was nearing the end of the thesis. Most people who have written doctoral dissertations will claim that it feels that one can see the light at the end of a dark tunnel. Well, this is how I felt at that time. However, Heywood was not convinced. His style of supervision suited me fine though other students, including my friend Chandramohan, complained against him since he was prone to losing the work they submitted to him. Moreover, they wanted more detailed comments than he gave. I was happy not to submit my work to him just as he was happy not to ask for it. We met sometimes but mostly socially when he talked about the Bronte sisters and that Heathcliffe was a slave abandoned by his mother in England. However, if I told him what I was doing, he understood at once and his words, laconic though they were, were very insightful. When I told him that my work was about to end he said:

“Tareeq, the animal called PhD does not walk in two years.”

I could have corrected him that it was only one year since I had started working on Forster since I had wasted one yar on publishing on Lawrence to prove him and his ilk wrong or on the “baggy monster” which was my earlier thesis. However, for once I kept quiet and Heywood said.

“Show me the interdiction and the conclusion and then we will see.”

After seeing these two documents he wrote on one: “Don’t change a word.” Then he said he would “throw me to the lions.” These lions, it turned out, were two famous professors of English literature. He himself, true to British fashion at that time, would not even be there when the lions ate me up. This made me start scribbling furiously.

By November, Hana decided to go back to Pakistan. She said it would cost us less as my scholarship would end by March. In fact, she confessed she was morbidly scared of a rapist, someone like the Yorkshire Ripper, who was reported to enter houses to rape women. I did not really want her to go but the argument about the money and the fear were both persuasive. So, one day we left our first house and went to stay with Laiqa. Hana had to leave in a month or so, and I would stay with Soomro Sahib and his friends till I submitted my thesis. We both regretted having left our house the very same day. We felt so out of place and powerless. Laiqa was trying to make us comfortable but we felt so bad. But the time passed and I said goodbye to Hana at Heathrow. Then I moved into the house of the three friends and washed the dishes while one of them cooked for everybody. Chandramohan’s scholarship had ended and we too did not have a house to lodge him and, since Heywood had not allowed him to move from MPhil to PhD, he had gone to Algeria to earn enough money to support his studies. Being a very good friend of mine, he came to see me but only once. Soomro Sahib was good company but I felt very lonely and bad and I missed my friends. However, I did not become so depressed as to stop functioning. The decision of being alone at that critical time of my work could have been disastrous especially as everybody went away later. I and Hana now look back with horror at what might have happened had I fallen ill then. Moreover, Hana did not like being dislocated and we think Tania too might have missed me. So, all in all, it was a wrong decision.

The snowy, desultory winter days were now upon us. The Christmas of 1984 was the worst and loneliest time of the year. I was all alone in that dark house when Jesus, who had been my neighbour at 18-Victoria Road, invited me to lunch. I was profoundly grateful to him. However, somehow, my thesis was submitted in February 1985 i.e. two years and two months after I had got admission in this doctoral programme. After that I read voraciously as usual but the best thing was that there were people once more to talk to. One evening my friend Naveed, the one who claimed to be a lady’s man, took me and Chandramohan to a discotheque. Naveed Sahib boasted all the way about his being a latter-day Casanova or Don Juan, and I and Chandramohan, he said with great pity, were greenhorns. Both of us pointed out that for a dance in a disco one would need girls. Naveed Sahib condescended to smile upon our ignorance.

“Girls,” he pontificated, “the problem is keeping them away; not allowing just anybody to dance with you. One selects the best. They will fight with each and fall over each other to dance – with me.”

Naveed Sahib did not put this boast in these very words but this was the gist of his remarks. So off we went to the disco where deafening noise greeted us. I had been in a disco once with Dave and Billie so I knew about the torture. Chandramohan had also been thorough it but in Algeria where, he said, the noise had been impossible. Whether he actually got to dance with any girl was a moot point and I, knowing Chandramohan’s incompetence in that department, assumed that he sat in some corner discussing Marx and Alex La Guma with somebody just as I had done in England. Anyway, Naveed Sahib seemed unfazed. He was almost blasé. We followed him about like little lambs. Soon it became clear to the meanest intelligence that three men, smiling sheepishly and nursing drinks, could not possibly get dancing partners. Naveed Sahib, however, boldly plunged into the gyrating couples and abandoned himself to solo acrobatics. I and Chandramohan followed him and found him moving as if doing PT in a South Asian college all alone. We discussed Marx and then ducked out within ten minutes. We got no female company – except, of course, the daughter of the grape – and Naveed Sahib put all the blame upon us. He plunged in again to a part of the hall where we could not see him. But after an hour of acrobatics even Naveed Sahib settled for the daughter of the grape. Then we went home – definitely not “the six hundred!” of the “Charge of the Light Brigade” fame.

My examination was scheduled on the 1st of April 1985. Professor Saunders was the external examiner and the internal one was Professor Norman Blake, Professor of English at Sheffield and author of several research works. In our department he had a formidable reputation. When I went in one of the examiners said:

“You approve of biographical criticism. This means that what this professor has been saying for twenty-eight years is wrong.”

I explained that I did not say it was wrong but that there could be other ways of looking at a work of literature and biography was one. I gave examples from many writers and not only Forster. Then the other examiner came to the symbolic aspects of my study and I told him that without understanding the symbols which related to Forster’s life, his real meaning could not be understood. There was a surface level and there was a deeper level and the latter was available when one knew Forster’s sexual orientation. At last, the viva was over and I was told to go out for a while. After about five minutes I was called in. Both the examiners beamed and congratulated me. They told me that my thesis had passed. As my supervisor and others told me, this was a triumph because the conservative British academics did not give such pride of place to sexual orientation in the understanding of literature at that time. It was still a tabooed topic and I had, as it were, “rocked the boat of the British academic establishment” as my supervisor Christopher Heywood put it. However, since the examiners had suggested only minor corrections, all typographical errors, I did them in three days and that was that.

My few friends, Naveed Sahib, Soomro Sahib etc. wished me joy and I rang home about the good news. Then, on 14 April I got my beard shaved. It was a huge, bushy, Marx (or Sir Syed) type of beard of which I have fond photographs. I had allowed it to grow to such a majestic length only to avoid shaving. Then I went to Uncle Barni’s house in London. That evening, while shopping for gifts, I finished all my money. Next morning when I boarded the airport bus, I had no cash. I offered a box of chocolates to the driver and he accepted it. So, when I boarded the Turkish Airlines plane at Heathrow, I had no cash at all. This perhaps was the last adventure, the last foolhardy thing, I did by choice. I travelled all the way to Pakistan, changing planes at Ankara, without a penny in my pocket. As I was flying over some Arab country, I saw fires below (oil wells perhaps?) and just then I thought I would write a history of Pakistani literature in English. This topic had no connection with what I saw but the moment of the genesis of my research project is engraved on my mind. I had a vague idea that, though people had written histories of other non-native literatures in English, there was no such history of Pakistan’s literature written originally in English. So, with two ideas—that I would look for an academic position and write this book—I was being hurtled through space. When I arrived at Karachi airport Riaz was there to receive me. I spent a day with Uncle Shafi Ullah. Azam arrived with visiting cards for me from Hyderabad where he was posted. Then I flew to Lahore reaching Pindi by the afternoon of 15 April 1985. Seeing my parents, and especially Ammi, and Hana and little Tania was overwhelming. I could hardly believe my good luck. I was overjoyed at being in Pakistan and with my family.