Afghanistan is slowly but surely headed towards an implosion. And that’s going to be an explosive problem for the entire region, especially Pakistan.

Violence has been increasing through the year but has seen a sharp spike since the US/NATO troops have begun to withdraw. The momentum of the withdrawal seems to corroborate reports that most US troops will have left Afghanistan by July 4, America’s Independence Day, with just a small contingent left behind for local protection of the US embassy.

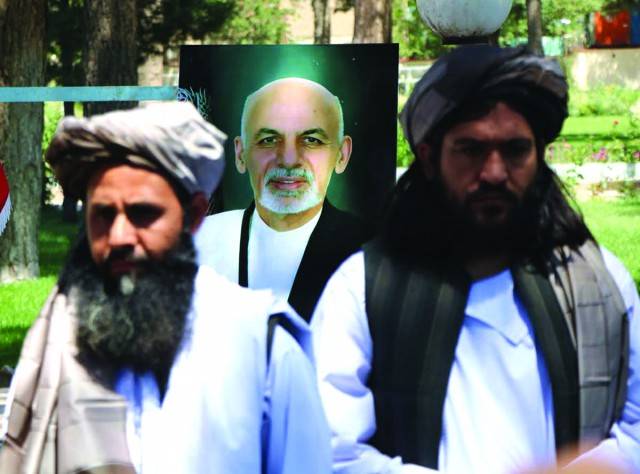

Be that as it may, the ground situation has undergone a major change since mid-April 2021 when US President Joe Biden announced an unconditional withdrawal, saying that it was ‘time to end’ America’s longest war. This was very different from an earlier effort in March when US Secretary of State Antony Blinken had written a letter to Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani, proposing new plans to break the intra-Afghan talks gridlock and advance the peace process.

The letter, leaked to Tolo News and reportedly widely, urged Ghani to “move matters more fundamentally and quickly toward a settlement and a permanent and comprehensive ceasefire.” The proposals included a UN-convened conference of key regional states, a meeting between the Afghan government and the Taliban hosted by Turkey and a 90-day reduction in violence “intended to prevent a spring offensive by the Taliban.”

Interestingly, Blinken had also recommended “a roadmap to a new, inclusive government” and sequenced it as preceding “the terms of a permanent, comprehensive ceasefire.” In other words, Blinken was proposing an interim power-sharing government composed of Taliban and other Afghan leaders. He also urged Ghani to work towards “building a more united Afghan front for peace,” a reference to disunity between Ghani and the disparate Afghan political opposition as well as tensions within Ghani’s own camp.

Predictably, the letter was rejected by the Afghan government. Ghani has on several occasions spurned the idea of an interim government, stressing instead a comprehensive ceasefire and intra-Afghan talks. The Taliban, on the other hand, dismiss this sequencing, calling for an interim set-up that would lead to a ceasefire and deliberations on a new constitution.

With Biden’s April announcement of a withdrawal that is neither linked to nor contingent on an intra-Afghan settlement, the warring sides in Afghanistan have dug in. To be precise, efforts are still on through both the Doha process and other channels to get a breakthrough but it does not seem likely that one or both sides will come round anytime soon. The Taliban seem to think they have scored a win with an unconditional US withdrawal while Kabul, sensing the Taliban will continue to press for a coup de grace, feels it has no option but to resist the Taliban.

Australia has already shuttered its embassy. Britain is expediting relocation of its Afghan staff. According to one report, under Britain’s relocation scheme for former and current Afghan staff, over 1,300 workers and their families have been brought to the UK. More than 3,000 Afghans are expected to be resettled under the accelerated plans. Defence Secretary Ben Wallace has said it was “only right” to speed up the plans with former Afghan staff at risk of reprisals from the Taliban and other insurgent forces in the country.

As violence reaches Kabul and its surrounding areas, more western diplomatic missions are likely to close. The signal is obvious: the US and its allies have no Plan B and are expecting the worst: i.e., Afghan forces folding before a Taliban onslaught and the possibility of a civil war with the country being divided among several armed factions.

The US is already pushing Pakistan to be prepared to take in more refugees. However, Pakistan is not inclined to concede because of the number of refugees already present in Pakistan as well as the problems associated with more refugees coming in. Nonetheless, a collapsing Afghanistan is a major problem for Pakistan. Like the US and its allies, Pakistan too does not have a Plan B. It invested a lot in facilitating the Afghan peace process, but its influence has reached its ceiling.

The US continues to ask Pakistan to pressure the Taliban further. That is a tricky ask because Islamabad fears (quite reasonably) that if it were to coerce the Afghan Taliban, the effort could backfire. Rahimullah Yusufzai, probably one of the most incisive commentators on Afghanistan, said to me on my television programme that the Taliban were already unhappy with the pressure Pakistan was already applying on them. According to Yusufzai, they could begin to facilitate the regrouped TTP and even extend help to Baloch Raji Ajohi Sangar, the Baloch terrorist conglomerate which comprises three separatist terrorist groups and was formed in November 2018. In the meantime, the frequency of terrorist attacks in some parts of Balochistan and the erstwhile FATA has already increased. Pakistan does not want the problem to exacerbate.

In theory, the only way to head off the impending implosion is for regional state actors — Pakistan, Iran, China, Russia, Turkey and the CARs — to bring joint pressure to bear on both the Kabul government and the Taliban; to get Ghani to agree to an interim set-up and to force Taliban to reduce violence. The window for doing this is fast closing, though. As noted before, Ghani is averse to stepping down. Equally, the demand for an interim arrangement is not just what the Taliban want: Ghani’s political opposition also wants him to step down. This provides the regional actors with the leverage to put pressure on Ghani and his coterie. But, and this is important, such pressure will only be meaningful if the Taliban can also be forced into reducing violence. In other words, we are not looking for sequencing but simultaneity.

If this can be achieved — and it’s a big if — the next step should be to go for a comprehensive ceasefire and for all stakeholders to agree to the terms of an interim set-up which could then work towards a new constitution and system of government.

If this cannot be achieved, as is likely, regional actors should be prepared for a throwback to the nineties. That is a scenario in which anything could happen. How long could the current Afghan government and its security forces hold onto power; how much area would they control (they control about 30 per cent now with 50 per cent controlled by Taliban and 20 per cent being contested); how many satraps within the current ruling configuration would emerge with their own militias and areas of control; how will the Afghan economy fare, given that it already survives on external budgetary support; what kind of rule would we see in areas under Taliban control; what space would Daesh and other freelancers get in such a chaotic situation; what counterterrorism measures, if any, could the regional and extra-regional actors take to secure their interests; how effective would those measures be; what would stop regional and other actors from backing their preferred proxies… etc etc. The list of unknowns is long, but if the situation gets to that, Afghanistan will reflect Hobbes’s bellum omnium contra omnes.

In short, while efforts should and must be made to exploit the fast-closing window towards securing some kind of peace, we must also brace ourselves for storms ahead. This voyage is about to get rough.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He tweets @ejazhaider

Violence has been increasing through the year but has seen a sharp spike since the US/NATO troops have begun to withdraw. The momentum of the withdrawal seems to corroborate reports that most US troops will have left Afghanistan by July 4, America’s Independence Day, with just a small contingent left behind for local protection of the US embassy.

Be that as it may, the ground situation has undergone a major change since mid-April 2021 when US President Joe Biden announced an unconditional withdrawal, saying that it was ‘time to end’ America’s longest war. This was very different from an earlier effort in March when US Secretary of State Antony Blinken had written a letter to Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani, proposing new plans to break the intra-Afghan talks gridlock and advance the peace process.

The letter, leaked to Tolo News and reportedly widely, urged Ghani to “move matters more fundamentally and quickly toward a settlement and a permanent and comprehensive ceasefire.” The proposals included a UN-convened conference of key regional states, a meeting between the Afghan government and the Taliban hosted by Turkey and a 90-day reduction in violence “intended to prevent a spring offensive by the Taliban.”

Interestingly, Blinken had also recommended “a roadmap to a new, inclusive government” and sequenced it as preceding “the terms of a permanent, comprehensive ceasefire.” In other words, Blinken was proposing an interim power-sharing government composed of Taliban and other Afghan leaders. He also urged Ghani to work towards “building a more united Afghan front for peace,” a reference to disunity between Ghani and the disparate Afghan political opposition as well as tensions within Ghani’s own camp.

Regional actors should be prepared for a throwback to the nineties. That is a scenario in which anything could happen

Predictably, the letter was rejected by the Afghan government. Ghani has on several occasions spurned the idea of an interim government, stressing instead a comprehensive ceasefire and intra-Afghan talks. The Taliban, on the other hand, dismiss this sequencing, calling for an interim set-up that would lead to a ceasefire and deliberations on a new constitution.

With Biden’s April announcement of a withdrawal that is neither linked to nor contingent on an intra-Afghan settlement, the warring sides in Afghanistan have dug in. To be precise, efforts are still on through both the Doha process and other channels to get a breakthrough but it does not seem likely that one or both sides will come round anytime soon. The Taliban seem to think they have scored a win with an unconditional US withdrawal while Kabul, sensing the Taliban will continue to press for a coup de grace, feels it has no option but to resist the Taliban.

Australia has already shuttered its embassy. Britain is expediting relocation of its Afghan staff. According to one report, under Britain’s relocation scheme for former and current Afghan staff, over 1,300 workers and their families have been brought to the UK. More than 3,000 Afghans are expected to be resettled under the accelerated plans. Defence Secretary Ben Wallace has said it was “only right” to speed up the plans with former Afghan staff at risk of reprisals from the Taliban and other insurgent forces in the country.

As violence reaches Kabul and its surrounding areas, more western diplomatic missions are likely to close. The signal is obvious: the US and its allies have no Plan B and are expecting the worst: i.e., Afghan forces folding before a Taliban onslaught and the possibility of a civil war with the country being divided among several armed factions.

The US is already pushing Pakistan to be prepared to take in more refugees. However, Pakistan is not inclined to concede because of the number of refugees already present in Pakistan as well as the problems associated with more refugees coming in. Nonetheless, a collapsing Afghanistan is a major problem for Pakistan. Like the US and its allies, Pakistan too does not have a Plan B. It invested a lot in facilitating the Afghan peace process, but its influence has reached its ceiling.

The US continues to ask Pakistan to pressure the Taliban further. That is a tricky ask because Islamabad fears (quite reasonably) that if it were to coerce the Afghan Taliban, the effort could backfire. Rahimullah Yusufzai, probably one of the most incisive commentators on Afghanistan, said to me on my television programme that the Taliban were already unhappy with the pressure Pakistan was already applying on them. According to Yusufzai, they could begin to facilitate the regrouped TTP and even extend help to Baloch Raji Ajohi Sangar, the Baloch terrorist conglomerate which comprises three separatist terrorist groups and was formed in November 2018. In the meantime, the frequency of terrorist attacks in some parts of Balochistan and the erstwhile FATA has already increased. Pakistan does not want the problem to exacerbate.

In theory, the only way to head off the impending implosion is for regional state actors — Pakistan, Iran, China, Russia, Turkey and the CARs — to bring joint pressure to bear on both the Kabul government and the Taliban; to get Ghani to agree to an interim set-up and to force Taliban to reduce violence. The window for doing this is fast closing, though. As noted before, Ghani is averse to stepping down. Equally, the demand for an interim arrangement is not just what the Taliban want: Ghani’s political opposition also wants him to step down. This provides the regional actors with the leverage to put pressure on Ghani and his coterie. But, and this is important, such pressure will only be meaningful if the Taliban can also be forced into reducing violence. In other words, we are not looking for sequencing but simultaneity.

If this can be achieved — and it’s a big if — the next step should be to go for a comprehensive ceasefire and for all stakeholders to agree to the terms of an interim set-up which could then work towards a new constitution and system of government.

If this cannot be achieved, as is likely, regional actors should be prepared for a throwback to the nineties. That is a scenario in which anything could happen. How long could the current Afghan government and its security forces hold onto power; how much area would they control (they control about 30 per cent now with 50 per cent controlled by Taliban and 20 per cent being contested); how many satraps within the current ruling configuration would emerge with their own militias and areas of control; how will the Afghan economy fare, given that it already survives on external budgetary support; what kind of rule would we see in areas under Taliban control; what space would Daesh and other freelancers get in such a chaotic situation; what counterterrorism measures, if any, could the regional and extra-regional actors take to secure their interests; how effective would those measures be; what would stop regional and other actors from backing their preferred proxies… etc etc. The list of unknowns is long, but if the situation gets to that, Afghanistan will reflect Hobbes’s bellum omnium contra omnes.

In short, while efforts should and must be made to exploit the fast-closing window towards securing some kind of peace, we must also brace ourselves for storms ahead. This voyage is about to get rough.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He tweets @ejazhaider