Ambreen Butt is a leading Pakistani-American visual artist based in Dallas. She specialised in miniature painting from the National College of Arts, Lahore and moved in 1993 to the United States for her graduate studies. She did her Masters in Painting from Massachusetts College of Arts, Boston. Butt’s work has included drawing, sculpture, installation and painting and is displayed at several museums in the US.

Overall Butt has faithfully followed her traditionally honed miniature skills and the associated aesthetic sensibility to produce her body of work. “I am my lost diamond” and “I am all what is left of me” are some of her works done at larger scale. Despite the politically strong message in her works, Butt’s oeuvre has the visually pleasing colour schemes of traditional crafts. Moving countries has played an “enormous role in evolving her visual vocabulary” and as a “South Asian Muslim Woman” in the US she faced her own complex challenges. She worked hard to respond to those challenges through her faith and by successfully developing her own aesthetics.

Butt feels that her work would have always responded to the socio-political milieu around her, no matter where she lived. Her subject matter is mostly centred around “war, violence, women and human rights” – both locally and globally. She is of the view that “the individual events might be different but the work addresses larger global issues that are tied to us at different levels.” She provides example of two of her series that address a similar context. ‘I must utter what comes to my lips’ was, according to her, “in response to the events of September 11 and its effects on individual lives while living in the US”. Another series ‘I need a hero’ was inspired by the story of Mukhtaran Mai. These two sets of works involved completely different worlds but are connected through their themes of humanity, and more importantly for Butt, they show her experiences emerging from her “bicultural identity.”

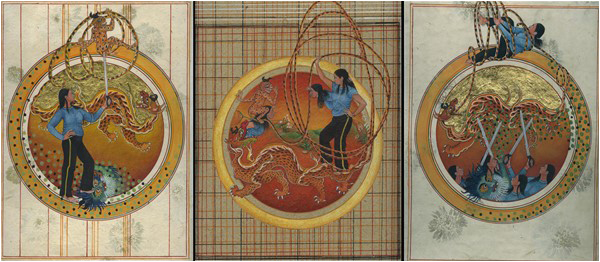

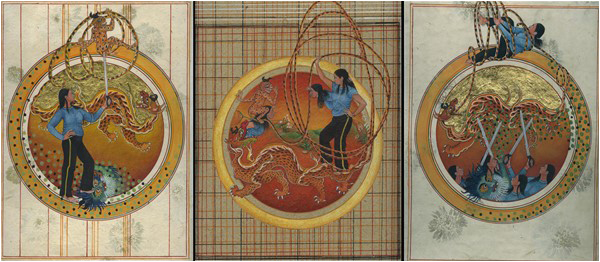

As part of her work she also challenged the stereotype of looking at a female from a male gaze. As a result her female characters emerge as protagonists in sweat pants and T-shirts, “sometimes holding a sword in her hand and engaged in a battle just like the old Amir Hamzah or Rustam and Suhrab.” In the series, “I need a hero”, the woman warrior fighting demons is beautiful like traditional miniature yet is fully empowered and confident.

Looking for unconventional materials to integrate her miniature sensibility, Butt used Mylar paper in the mid-90s and tried to create an alternate surface that could be a reminiscent of ‘wasli’ (multilayered paper prepared traditionally by miniature artists for their work). Later she also worked with resin to create large-scale installations using a one-mark-at-a-time strategy, which is also particular to miniature painting.

As an artist Butt deeply enjoys the repetitive processes involved in preparing a painting in miniature – she not only finds it meditative but uses it as a starting point to build a bigger body of work such as her “Pages of Deception” which is made of shredded paper – a technique that she has used to prepare some other interesting works including large-scale dollar bills from officially retired bills. In her view, using shredded paper in her body of work also shows how hollow or deceptive some of the substantive aspects of life are, such as the value of money or seeing only the image of a text without realising or understanding its true meaning.

During an artist residency by Butt at the Dartmouth College, famous US artist Frank Stella was also there as a Montgomery fellow. Butt recalls interacting with Stella, who saw her show and appreciated the work – especially the torn text pieces, commenting that the drawing was “pretty neat it looks like calligraphy and yet it’s not calligraphy.”

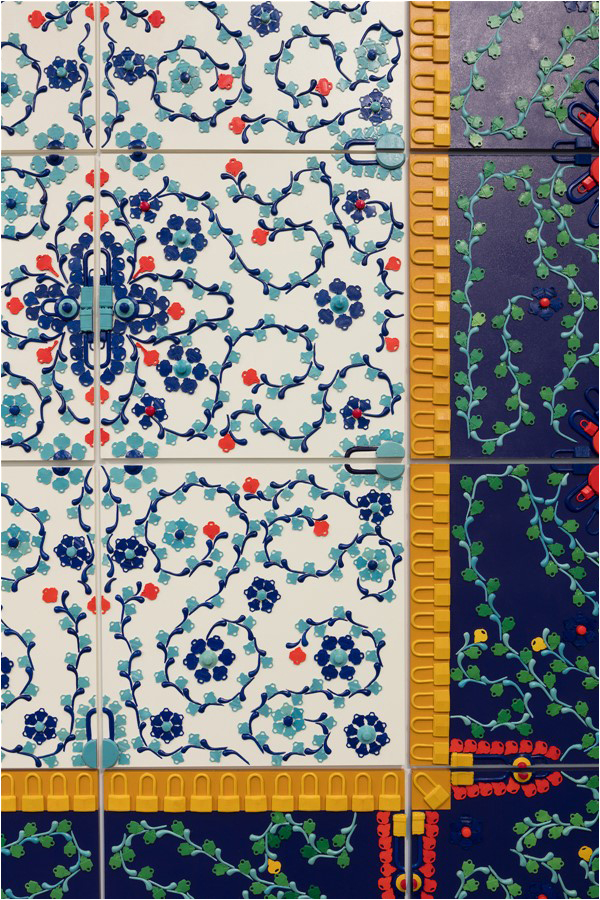

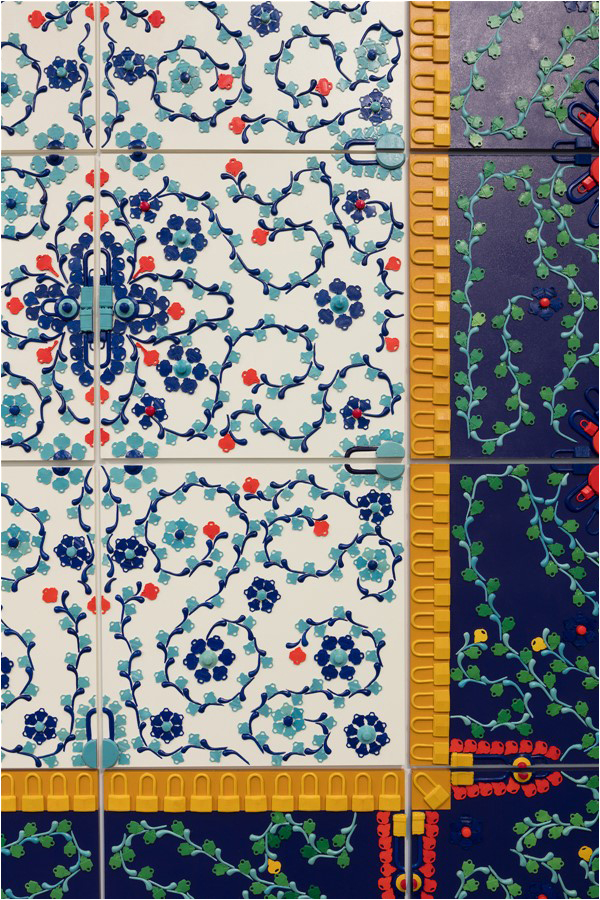

A continuous dialogue relating to her hybrid existence is evident in Butt’s work. She has now moved from figurative to more project-based work. Butt has worked on a commission from the US Embassy in Islamabad in which, according to her, the “text-based patterns in blues or greens are a reminiscent of traditional kashi-kari tile designs used for centuries to decorate prominent public buildings, mosques and palaces.”

She further explains: “After working with figures for many years,I am now exploring the role of redundant mark-making or ‘pardakht’ as a mean of creating patterns. And text as a visual image. I have done several works in multiple mediums, stretching the limits of mark-making – that includes text-based works and resin casted digits.”

As for how to place her work or where is situated as an artist in terms of locale, Butt is of the view that “labels are hard. As the trends in the art world keep changing, new hashtags are invented. Artists also try to fit their work in the contemporary dialogue. The truth is: it’s a matter of survival in an already marginalised field.”

She wants her work to be “universal enough to be able to transcend into any ideology and be accessible to any kind of audience based on their own history.” With the rigorous thinking involved and intensive labour undergirding her creativity, the message in Butt’s work resonates across borders.

The writer can be reached at smt2104@caa.columbia.edu

Overall Butt has faithfully followed her traditionally honed miniature skills and the associated aesthetic sensibility to produce her body of work. “I am my lost diamond” and “I am all what is left of me” are some of her works done at larger scale. Despite the politically strong message in her works, Butt’s oeuvre has the visually pleasing colour schemes of traditional crafts. Moving countries has played an “enormous role in evolving her visual vocabulary” and as a “South Asian Muslim Woman” in the US she faced her own complex challenges. She worked hard to respond to those challenges through her faith and by successfully developing her own aesthetics.

Butt feels that her work would have always responded to the socio-political milieu around her, no matter where she lived. Her subject matter is mostly centred around “war, violence, women and human rights” – both locally and globally. She is of the view that “the individual events might be different but the work addresses larger global issues that are tied to us at different levels.” She provides example of two of her series that address a similar context. ‘I must utter what comes to my lips’ was, according to her, “in response to the events of September 11 and its effects on individual lives while living in the US”. Another series ‘I need a hero’ was inspired by the story of Mukhtaran Mai. These two sets of works involved completely different worlds but are connected through their themes of humanity, and more importantly for Butt, they show her experiences emerging from her “bicultural identity.”

As part of her work she also challenged the stereotype of looking at a female from a male gaze. As a result her female characters emerge as protagonists in sweat pants and T-shirts, “sometimes holding a sword in her hand and engaged in a battle just like the old Amir Hamzah or Rustam and Suhrab.” In the series, “I need a hero”, the woman warrior fighting demons is beautiful like traditional miniature yet is fully empowered and confident.

Her female characters emerge as protagonists in sweat pants and T-shirts, "sometimes holding a sword in her hand and engaged in a battle just like the old Amir Hamzah or Rustam and Suhrab"

Looking for unconventional materials to integrate her miniature sensibility, Butt used Mylar paper in the mid-90s and tried to create an alternate surface that could be a reminiscent of ‘wasli’ (multilayered paper prepared traditionally by miniature artists for their work). Later she also worked with resin to create large-scale installations using a one-mark-at-a-time strategy, which is also particular to miniature painting.

As an artist Butt deeply enjoys the repetitive processes involved in preparing a painting in miniature – she not only finds it meditative but uses it as a starting point to build a bigger body of work such as her “Pages of Deception” which is made of shredded paper – a technique that she has used to prepare some other interesting works including large-scale dollar bills from officially retired bills. In her view, using shredded paper in her body of work also shows how hollow or deceptive some of the substantive aspects of life are, such as the value of money or seeing only the image of a text without realising or understanding its true meaning.

During an artist residency by Butt at the Dartmouth College, famous US artist Frank Stella was also there as a Montgomery fellow. Butt recalls interacting with Stella, who saw her show and appreciated the work – especially the torn text pieces, commenting that the drawing was “pretty neat it looks like calligraphy and yet it’s not calligraphy.”

A continuous dialogue relating to her hybrid existence is evident in Butt’s work. She has now moved from figurative to more project-based work. Butt has worked on a commission from the US Embassy in Islamabad in which, according to her, the “text-based patterns in blues or greens are a reminiscent of traditional kashi-kari tile designs used for centuries to decorate prominent public buildings, mosques and palaces.”

She further explains: “After working with figures for many years,I am now exploring the role of redundant mark-making or ‘pardakht’ as a mean of creating patterns. And text as a visual image. I have done several works in multiple mediums, stretching the limits of mark-making – that includes text-based works and resin casted digits.”

As for how to place her work or where is situated as an artist in terms of locale, Butt is of the view that “labels are hard. As the trends in the art world keep changing, new hashtags are invented. Artists also try to fit their work in the contemporary dialogue. The truth is: it’s a matter of survival in an already marginalised field.”

She wants her work to be “universal enough to be able to transcend into any ideology and be accessible to any kind of audience based on their own history.” With the rigorous thinking involved and intensive labour undergirding her creativity, the message in Butt’s work resonates across borders.

The writer can be reached at smt2104@caa.columbia.edu