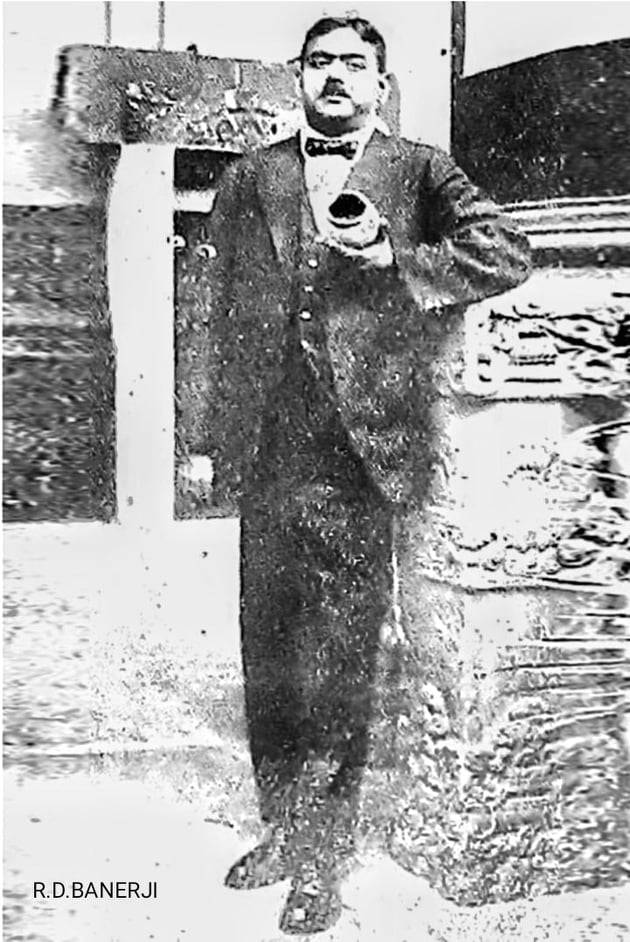

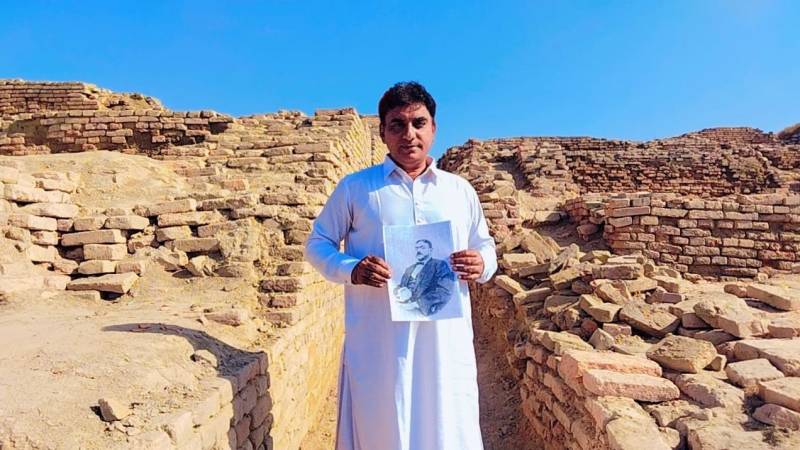

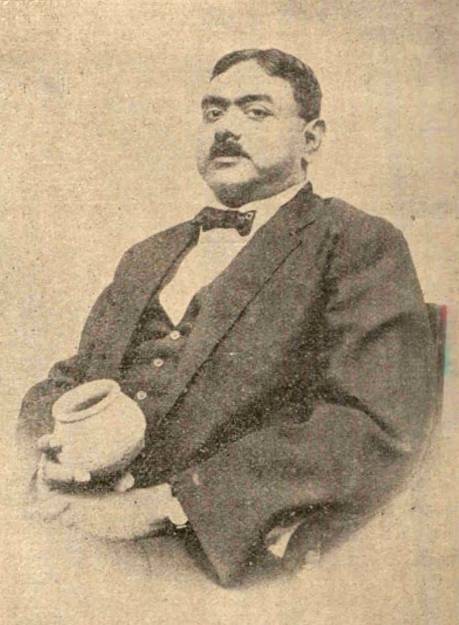

Rakhal Das Bandyopadhyay (RDB) was an Indian archaeologist, museum expert, epigraphist, numismatist, historian, linguist, novelist and photographer. Banerji was born on 12 April 1885 in Berhampore, in the District of Murshidabad, West Bengal, India. He died at Kolkata on 23 May 1930. He is also known as the first excavator of Mohenjodaro; the largest settlement of the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation, that flourished around 2600-1900 BC. Mohenjodaro is believed to be among the world's earliest major cities, contemporaneous with the civilisations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia & Minoan Crete.

Classification of Monuments by the orders of the Commissioner in Sindh

Sir Henry Staveley Lawrence served as Commissioner in Sindh from 1916 to 1919. Sir Henry Staveley Lawrence requested RD Banerji to classify the archaeological and historical sites in Sindh. RD Banerji writes that:

“In 1917, I was requested by the Commissioner in Sindh to advice him regarding the classification and the declaration of a number of ruins in Sindh as protected monuments according to the Ancient Monuments Preservation Act of India (Act VII of 1904 S.C) In accordance with this request I started examining all such ancient ruins and sites of Sindh in October 1917”. He writes that “My first visit to Alor was paid in October 1917” (Mohenjodaro: A Forgotten Report compiled by RDB, page 23). Later on Banerji toured Karachi and Hyderabad, as also Sukkur and Rohri. Again, in March 1918, he had taken his assistant superintendent VS Sukhthankar with him there.

There were 18 beds of the River Indus between Mohenjodaro & Khirthar Range

RD Banerji visited the ruins of Vinjnot on 20 December 1919. From December 1919 to December 1922, surveying between the present channel of the River Indus and the Khirthar Range, Banerji came across no fewer than 18 old beds of the River Indus. Banerji conducted this survey in the western parts of the Shahdadkot, Kamber, Ghaibidero, Kakar, Johi and Sehwan areas of Larkana District. Mostly these were backward and remote areas at that time.

RD Banerji travels from Larkana to Dokri and finally reaches Mohenjodaro

Nayanjot Lahiri writes in her book Finding Forgotten Cities, 2005 that:

“Banerji must have breathed the same Larkana dust on the train which took him to Dokri, the small urban headquarters of Labdarya taluka. The railway station near Dokri was the one closest to Mohenjodaro, 8 miles distant. From there, Banerji would have travelled by Tonga along a stretch of unmetalled road. On reaching the mounds of Mohenjodaro (which means Mound of the Dead), Banerji was surprised and delighted because, although the ruins were well known in the immediate neighbourhood, their character and importance had not been captured in any archaeological account of Sindh. As he well knew, Mohenjodaro was not listed as an ancient site in the revised list of ancient monuments within the Bombay Presidency. This was astonishing because what he saw before him was an extensive site of multiple rolling mounds over an area of about 2 square miles, visible from a great distance. Most significantly, a Buddhist stupa crowned the highest part of the ruins. Banerji spent a day there” (Page 209)

In Search of Alexander’s Greek Victory Pillars and Inscriptions

Dr Suniti Kumar Chatterji, Khaira Professor of Indian Linguistics, Calcutta University, writes:

“In the meanwhile, Mr. Rakhal Das Banerji, M.A. (then Superintendent of Archaeological Survey, Western Circle, now of the Eastern Circle) was surveying along the old dried up channels of the Satlaj, and the Indus, in South Panjab, Bikaner, Bahawalpur and Sindh, during the five winters of 1918-1922. His great object was to discover, if possible, the twelve stone altars with Greek and Indian inscriptions which were erected by Alexander the Great when he commenced his retreat from the Satlaj. He followed the dried course of the lost Hakro River in Bahawalpur State, up to the town of Reti in Sukkur District in Sindh. Here he found and surveyed numerous old beds of the Indus, which numbered as many as 17: and he noted remains of 27 big towns and of some 53 small ones in Upper Sindh Frontier, Sukkur and Larkana (“Dravidian Origins and the Beginnings of Indian Civilisation” by Dr. Suniti Kumar Chatterji, Calcutta University, The Modern Review, 1928, Page 671)

Hunting Scene of Cheetul in the forest of Dokri, District Larkana 1917

RD Banerji writes that, “I stumbled upon Mohen-Jo-Daro by chance. In October, 1917, while I was out hunting for Cheetul-or red spotted deer-in the neighbourhood, I lost my way and strayed into its site. There, I found a Chert or Scraper of Nummulitic Flint of the same type as those discovered by Blanford at Rohri, -now in the Indian Museum, Calcutta,-in the neighbouring district of Sukkur and with which Sir Thomas Holland had made me familiar as early as 1903” (“An Indian City Five Thousand Years Ago” by Rakhaldas Banerjee, The Calcutta Municipal Gazette, 17 November 1928, Pages 92 & 93)

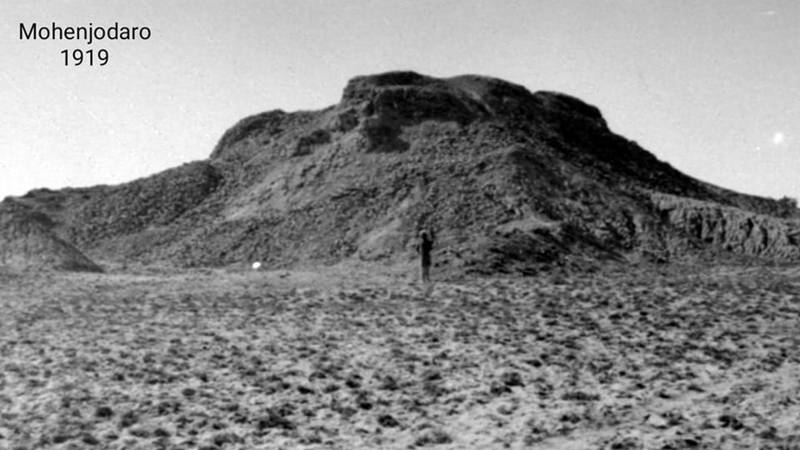

Mohenjodaro revisited by RD Banerji in December 1919

JL Rieu was appointed Commissioner in Sindh in May 1919. Previously he had served as an ICS Officer and was Collector of Shikarpur District in Sindh. The ruins of Mohenjodaro were situated in Bagi Forest of Taluka Dokri at that time. JW Smyth writes in the Gazetteer of the Province of Sindh Larkana District (1919), “Dokri, a small town in North Latitude 27 22 and East Longitude 68 8, is the headquarters of the Labdarya taluka and is situated on the right bank of the western Nara Canal. It has a railway station one and a half miles distant. The town had a population of 1,500 at the census of 1911 and contains a District Bungalow, Kecheri, Police Lines, Dispensary, Vernacular School, Post Office and Musafirkhana. The roads leading to this town are shaded by magnificent avenues of trees” (Page 38 & 39)

RDB mentions 15 December 1919 as the date on which he was at Dokri.

Submission of the first Report on Mohenjodaro

Mr RD Banerji submitted his first report on Mohenjodaro in 1920 which was published later in Archaeology: Progress Report of the Archaeological Survey of India, Western Circle, for the year ending 31 March 1920, Calcutta, 1921. This report reads as follows:

VIII. Muhen-Jo-Daro

55. The ruins at Muhen-Jo-Daro lie at a distance of 6 miles from the Railway Station at Dokri on the Rohri-Kotri Section of the N.W. Railway. The Locality does not seem to have attracted notice before though the height of mound and the extensity of the ruins is well known in the neighbourhood. The ruins cover an area of about 2 square miles and are visible from a distance. They are not mentioned in the revised list of ancient monuments in the Bombay Presidency, but were visited by my predecessor in 1913.

56. The ruins consist of vast mounds of burnt bricks surrounded by smaller ones. In the centre of this area is a very high mound about 80 to 90 feet above the level of the surrounding country. This is called Muhen-Jo-Daro. The top of the entire mound consists of debris and brick bats but here and there loose debris has slipped away exposing straight walls of burnt bricks. This mound is about 600 feet in length and 200 feet in breadth. In one place on this mound there is the drum of a stupa made of sun dried bricks. Only the shell of the drum remains as the core has been excavated to a depth of some 30 to 40 feet by treasure seekers. The inhabitants of the surrounding village have dug out and removed bricks from this mound from time immemorial and do so even now. Some of these people who do not acknowledge to have excavated this mound for bricks within the last ten or twelve years, state that when they dug for bricks previously, they found the entire mound to consist of a huge platform, of burnt bricks on which were built numerous round hemispherical objects of burnt as well as sundried bricks.

57. Close to this platform of Stupa there is another mound which is the second largest in this place. This appears to have been a temple or monastery as the old villager’s state that they found rows of small square chambers arranged around a square courtyard in this mound. Search among the ruins led to the discovery of numbers of carved bricks but no human figures or images were found. The villagers are unanimous in stating that no coins have even been found in any of these mounds.

58. These two mounds are surrounded by numerous small mounds which represent the ruins of the village or township which had grown around the Stupa and temple in the height of their glory. The Stupa at this place is much higher than the Stupas at Depar Ghanghro or Mirpur Khas and appears to have been the largest and highest Buddhist Stupa in the country of Sindh. The Stupas and the surrounding ground is full of Saltpetre or some other Salt which is carried away and sold as a manure. The digging for bricks and the removal of this sort of manure constitute a serious danger to the structures that may lie under the covering of loose brick bats and debris and therefore steps ought to be taken to stop excavation in this area immediately (Archaeology: Progress Report of the Archaeological Survey of India, Western Circle, for the year ending 31 March 1920, Calcutta, 1921, Page 79, 80)

Declaration of Mohenjodaro as Protected Site by the Government of India

On the orders of British Government of India dated 11 October 1920, the Buddhist Stupa and Monastery of Mohenjodaro were declared as Protected Monuments. Besides this the fort of Sehwan, Dhamraho Jo Daro and Jhukar were also declared as protected monuments in Larkana District. About Harrapa, E .J. H. Mackay writes, “In 1921, Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahini conclusively proved that the remains at Harrapa went back to a very early period, but to what period it was then impossible to say.” (Further Excavations at Mohenjodaro, 1934, Page 206)

Commissioner in Sindh transfers Ruins to the excavator…

Mr JL Rieu, ICS Commissioner in Sindh was pleased to transfer the entire area (750 Acres), then known to be covered with ruins to the Archaeological Department by Order No, 321 AHR.D, dated 10-1-1922 and handed over to RDB by an Assistant of the Deputy Conservator of Forest in Sindh. The area transferred was surveyed and a plan showing the general contour of the ruins was prepared.

Who were the influentials of Dokri Taluka during Mohenjodaro excavation in 1922?

When RDBanerji started excavations at Mohenjodaro in 1922 following were landlords, zamindars and notable figures in Dokri Taluka: 1) Rai Sahib Anandram of Badeh 2) Wadero Ghulam Umer Unar 3) Seth Kotu Mal of Garelo 4) Wadero Shafi Muhammad Junejo 5) Wadero Muhammad Musa Bughio 6) Wadero Abdul Kadir Bughio 7) Wadero Farid Khan Jatoi 8) Wadero Faqir Muhammad Unar & 9) Seth Jamiat Rai of Garelo. When His Excellency the Governor of Sindh Sir Robert Francis Mudie visited Mohenjodaro Archaeological Site on 13 January 1946 from 9:00 to 12:00 these notables were scheduled for interviews with the Governor and EX. Eng: ND/RC at Taluka Office Dokri. On arrival of His Excellency the Governor of Sindh, the party included Miss Mudie and Miss Meaqueen. The DC Larkana, Dy: S.P. Larkana and Mukhtiarkar of Dokri.

Geographical Situation of Mohenjodaro at the time of first excavation

RD Banerji writes in his report:

“At Mohenjodaro the oldest bed of the River (Indus) was found within a short distance of the ruins. This old bed is distinct from the Western Nara on the right bank of which the modern village of Dokri is situated. The road from Dokri crosses one deserted channel of the Indus before reaching Mohenjodaro. A second old bed from a loop around the ground covered with low scrub, consisting of Babul (Acacia Arabica) and Camel thorns (Tamarisk Indica) which surrounds the ruins pf the ancient city of Mohenjodaro. The second bed is still called a Dhandh, which means in Sindhi Language the dried up channel of a river. A small hamlet, consisting of a few huts, named Dhandh stands on the bank of this dry river bed. To the north of the ruins of Mohenjodaro there is a thick reserved forest at the north eastern end of which this second dried river bed broadens, and is called the Lanyaro. Portions of the Lanyaro contain water in deep pits at all times of year and one of these water holes is visited by water fowl in very large numbers. The land on the left bank of the Lanyaro has not been properly surveyed and we do not know whether a portion of the town or its suburbs existed on the north bank of the old river also or not…On the south bank of the river, where the old city proper stood a broad paved street ended on the river’s edge, just apposite Site No. 1. This street followed a south easterly direction and divided the ancient city into two unequal halves […] The majority of the buildings of the ancient city were built in the area between the south bank of the old bed of River Indus and this main street.” (RDB Page 26, 27 & 28)

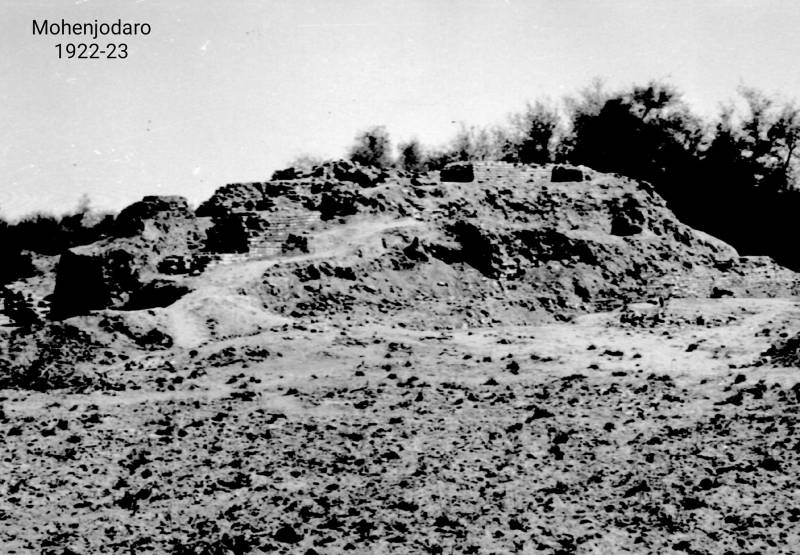

Mohenjodaro excavated by Mr. R.D Banerji in December 1922

RDB writes, “I decided to excavate at Mohen-Jo-Daro at the end of the working season of 1921-22 and paid my short visit to that site in December 1922. At my request, Mr J L Rieu, ICS Commissioner in Sindh was pleased to transfer the entire area (750 Acres), then known to be covered with ruins to the Archaeological Department by Order No, 321 AHR.D, dated 10-1-1922 and handed over to me by an Assistant of the Deputy Conservator of Forest in Sindh” (Page No 26)

He excavated Mohenjodaro at 3 sites from December 1922 to March 1923. He called those areas as (a) Site 1 (Stupa Complex Area) (b) Site 2 (Some 50 m north west of the Stupa) & (c) Site 3 (Some 120 m in the north edge of the stupa mound)

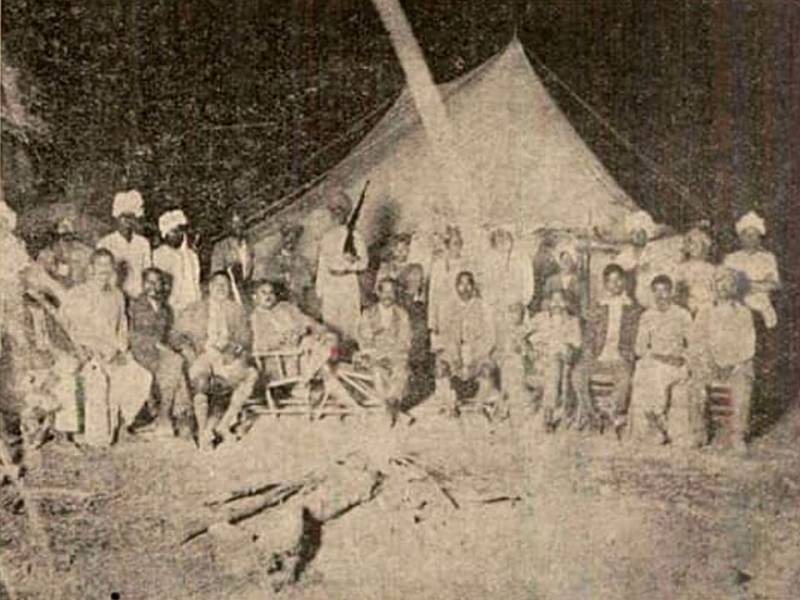

Who were the first excavators of Mohenjodaro?

VV Karandikur of The Bombay Public Works Department (PWD) conducted the survey with the assistance of four lower subordinates of the same department, all attached to the Western Circle of the Archaeological Survey of India viz. Messrs. NS Chikte, BG Punee, Dharamjay Samua and Daulatram Beliram Rajput. While excavating the slope of the platform on the northern side of the hollow stupa, NA Wartekar, Head draftsman of the Western Circle, discovered a number of fragments of frescoes with painted Kharoshthi and Brahmi inscriptions, JP Joglekar was the only photographer during first excavation season 1922-23. The contour survey was begun in the middle of December 1922 and was finished by the end of March 1923. All of the team was supervised by RD Banerji. According to Archaeology, Progress Report of the Archaeological Survey of India 1922, NS Chikte was deputed by the Superintending Engineer, Central Division, from the Sholapur District and joined his duties at Poona on 8 December 1920.

Mr Banerji bled his little finger while exploring Ghaibidero site

Nayanjot Lahiri writes in her book that,

“Ghaibi-daro in Larkana, according to Banerji, was quite crucial in confirming his intuition on the antiquity of Mohenjodaro. Apparently, his visit to it had coincided with a winter rain shower that accidently revealed a brick tower. Inside it, he found large-sized jars arranged in a row. When Banerji casually put his right hand into topmost of these, he found it poked by something sharp which apparently bled his little finger. This alarmed the local people, who suspected he had been bitten by a snake. However, when they broke the jar, instead of a serpent they found a stone scraper! One imagines that they must have been very relieved. But for Banerji the relief was combined with delight because this was the first time he had found a stone scraper in its original context and not on the other jars in the brick tower of Ghaibi-daro, were necropolitan in character and contained human bones. As he put it: “this was the first discovery of Neolithic or sub-neolithic stone implements underground and not on the surface. The discovery at Ghaibi-daro proved definitely that knives or scrapers of Neolithic flint was associated with pre-historic cremation burials and the specimen found by me at Reti, Alor, Mithodaro, Dhamraho, Badin and Mohen-Jo-Daro were not exactly chance finds”. According to Banerji, it was this discovery-of a stone tool in its original context-“which prompted me to start the excavation of Mohen-Jo-Daro immediately as I felt sure that it was one of the oldest sites in India”. (Page 220)

Banerji’s letter to Sir John Marshall, March 1923

Nayanjot Lahiri writes:

“For the moment, though, Banerji decided that it was time to touch base with Marshall and send him word of his finds. The field season was nearing its end and so, in March 1923, he wrote from Mohenjodaro to Sir John Marshall at Taxila the very letter with which we began our tryst with Rakhaldas Banerji. In that letter, Banerji asked Marshall for his advice regarding certain finds just made at Mohenjodaro”. (Page 225)

Marshall was full of warm praise. He replied to Banerji:

“I am immensely interested in your discovery of the Harappa seals at Mohenjo daro and I shall look very eagerly forward to hearing more about them when I come to Bombay. If you can establish the date and give any indication of the cultural connection of the people who produced these seals, you will achieve a great thing. It may be that the site at Mohenjo daro is smaller and in better preservation that the one at Harappa. In any case it will be well worth while following up your excavations. What I specially want to know is whether these seals were found in association with any of the coins or in circumstances which give an indication as to their age. At Harrapa Mr. Daya Ram came to the conclusion that they were pre-Mauryan. I wonder if this conclusion is borne out by your finds at Mohenjo daro.”

Last days of Banerji’s camp life at Mohen-Jo-Daro

Nayanjot Lahiri writes about the last days of Banerji’s camp life at Mohen-Jo-Daro as follows:

“If the dramatic discovery of Harappa-type seals at Mohenjodaro was the high point before Banerji’s exit from the Western Circle, the excavations also inflicted a heavy personal toll on him. Banerji was a chronic diabetic. In the months that he spent at Mohenjodaro in 1922-3, the piercingly cold winds, which frequently blow across the Larkana plains in winter combined with the rigours of camp life to make his condition much worse. He developed carbuncular sores and by the middle of March he became so sick that he had to leave camp and return to Bombay. During his sojourn in Bombay he met Marshall, who was preparing to sail for England. Marshall was keen to see what the Mohenjodaro seals looked like, and after-seeing casts of them both he and Banerji agreed that the script was a somewhat later development of the script on the seals from Harappa. In all likelihood, Marshall must have impressed upon Banerji the urgency of following up his amazing dig with a written record of his findings. There is a scene in Banerji’s letters-those that he wrote in April and May 1923-that he was impatient to get on with writing his report, tabulating the finds, and comprehending the pattern and implications of what he had unearthed. In the middle of April he wrote to Spooner, asking for Marshall’s address in England so that he could send him his report (still unwritten, of course) on the Mohenjodaro excavations. Spooner, officiating for Marshall, was naturally keen to learn more about Banerji’s finds. So, along with Marshall’s address, he let it be known to Banerji that he would appreciate a carbon copy of what Banerji sent Marshall. Spooner was, in fact, “most anxious to learn the details of such interesting work”. But Banerji had written up nothing till early May 1923 because of the breakdown in his health. He was unable to finish his report before he left for Calcutta on medical leave” (Page 230)

Due to office politics, RD Banerji took voluntary Retirement from ASI on 16 August 1926. In the same year 1926, RD Banerji compiled and submitted his report with photographs to Sir John Marshall. ASI never published this report in his archaeological publications. It was published under the title of Mohenjodaro: A Forgotten Report by Prithivi Prakashan, Vernasi India in 1984 with 166 pages.