This article aims to provide an overview of my ongoing research on the Indus script and to share preliminary findings with a wider audience. The intention is to make this new direction in Indus script research accessible to readers who may not have direct involvement in academic studies on the topic. By presenting this research in an accessible format, it is hoped that even non-specialist readers can engage with the progress being made in this field.

The central focus of this research is the decipherment of the Indus script as an alphabet of Sindhu Prakrit, which uncovers significant historical insights. The decipherment of an ancient and previously undeciphered script as an alphabet carries inherent self-evidence, and it provides a clear framework for analysis. Importantly, the suggestion that the Indus writing system may be alphabetical is not novel. For example, Rao Sahib’s earlier attempt at decipherment proposed an alphabetic structure for the Indus script. However, his work did not achieve universal academic acceptance due to the challenges of gaining consensus in this complex area of study.

The acceptance or rejection of any decipherment relies heavily on critical evaluation by experts and scholars, who rigorously assess the logical consistency and evidence supporting such claims. In this regard, the proposition of an alphabetic system offers a more straightforward and testable hypothesis compared to the complexities of logographic or logo-syllabic interpretations. These latter approaches often involve intricate and sometimes conflicting analyses, which can lead to ambiguities and make scholarly consensus difficult to achieve. The inherently personal nature of interpretative methods in these systems further complicates their evaluation, even when strong arguments are presented.

It is anticipated that this proposed decipherment as an alphabet will stimulate thoughtful critique and engagement from the scholarly community. Such dialogue is essential for refining and validating hypotheses in the study of ancient scripts.

This article presents a comprehensive approach to deciphering the Indus script by systematically analysing all its signs rather than focusing solely on specific ones. The study establishes an organised framework that categorises the signs through meticulous examination, ensuring that each is uniquely represented, akin to modern writing systems. This structured representation eliminates any potential for confusion or ambiguity. It is anticipated that this novel approach will captivate readers. This concise article aims to comprehensively summarise all facets and outcomes of the research, thereby mitigating any potential reader confusion or difficulty.

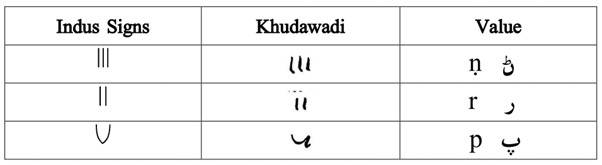

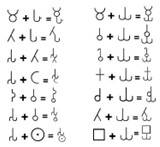

Indus script exhibits a diverse range of sign types. Fundamental to the script are basic signs, constituting its foundational elements. These basic signs can combine to form more complex structures. Compound signs with diacritical mark, composed of two basic signs, serve to modify or alter the meaning of other signs. Additionally, compound signs can encompass two or more basic signs, creating intricate combinations. Furthermore, some signs demonstrate the integration of multiple basic signs into a single, unified form. Finally, dual signs represent a unique category within the script.

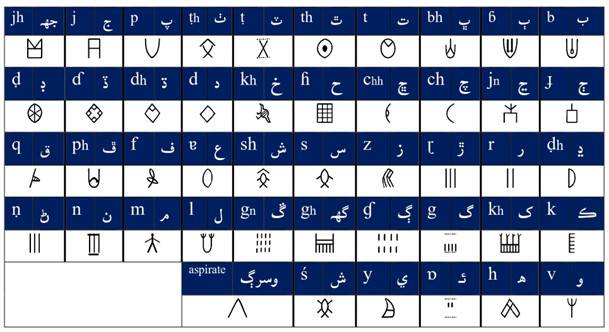

Through intensive observation and careful review, only 40 basic signs of the Indus script have been identified from the comprehensive lists provided by Mahadev, Parpola, and Wells (for details, refer to the book and related articles). These foundational signs, which cannot be further divided, appear predominantly in their original form as depicted on the seals. They are employed in specific sequences and configurations, refuting claims of an expansive set of Indus script signs. This limited number of basic signs strongly supports the hypothesis that the Indus script is alphabetic rather than pictorial, challenging traditional interpretations.

A thorough analysis of over 400 Indus script signs leaves no room for doubt regarding its nature. The writing system of the Indus Valley Civilisation represents a complete and comprehensive alphabet, marking a significant milestone in the history of script evolution. Considering the vast expanse of the Indus Civilisation and its communication networks, its influence extends to the Sumerian civilisation, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Arabian Peninsula. Evidence of this influence is seen not only in the widespread discovery of Indus seals but also in the exchange of writing practices.

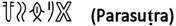

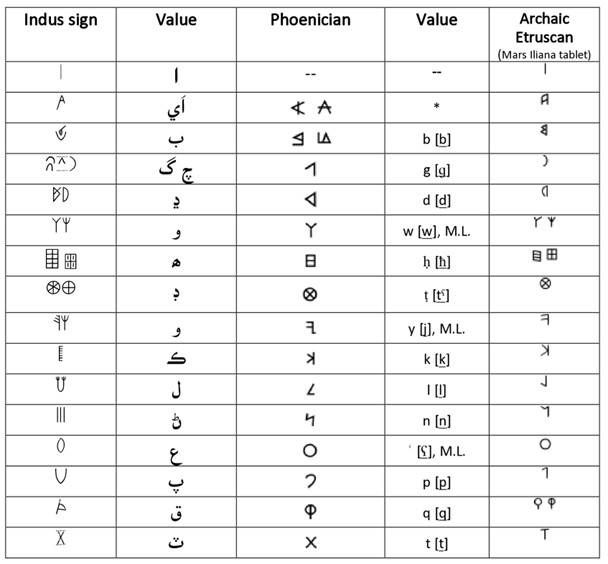

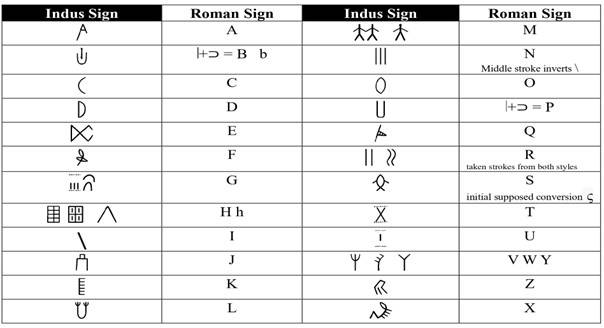

The idea that the Indus script forms the foundation of all subsequent alphabetic systems gains credibility when comparing its signs with those of later scripts. Similarities between these signs have been analysed, and corresponding values have been assigned, with illustrative examples provided below.

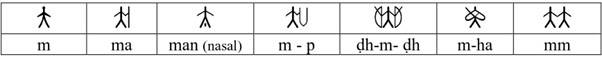

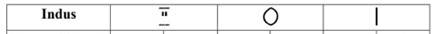

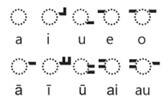

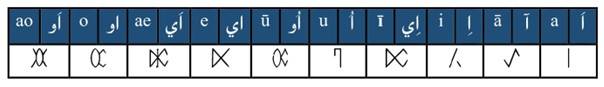

Identifying vowel and consonant sounds within the Indus script and determining their meanings is relatively straightforward. Notably, the three fundamental symbolic characters of the Indus script bear remarkable similarities to those found in many modern and ancient writing systems.

![]()

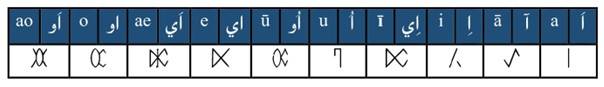

Basically, there are ten vowels or syllables in Sindhi. If the three vowel letters in Sindhi—borrowed from the Arabic script—are combined with diacritical marks in the same order, the resulting variations produce up to thirty distinct vowel sounds in Sindhi. This observation becomes particularly intriguing when compared to the Indus alphabet, where a similar structure reveals surprising parallels. The following table illustrates this fascinating relationship.

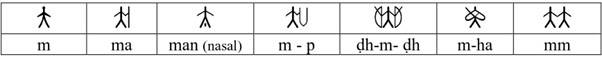

The Indus script incorporates the four semi-vowels and two nasal sounds. Their application within the Indus script is outlined as follows:

An explanation of the different forms of "R" can be found in the book "Alphabet of Sindhu Prakrit the Decipherment of Indus Script".

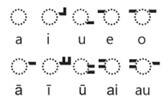

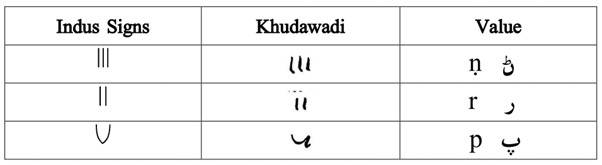

The phonetic values of Indus script symbols are determined by comparing them with other scripts and assigning corresponding values to phonemes or letters. Some examples are provided below.

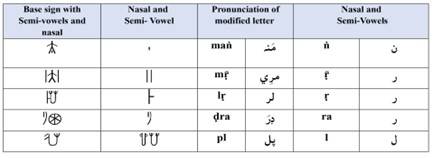

Three key signs sparked significant interest in the study of the Indus script. These correspond to letters from the Hatwaniki or Khudawadi script, which initially yielded promising and attention-grabbing results during preliminary tests. These findings generated considerable curiosity. Notably, these three signs rank among the most frequently used in the Indus script, both in terms of frequency and ease of writing.

Their structural simplicity and versatility may explain their presence, with minor variations, across ancient and modern scripts worldwide. Their consistent use over millennia has ensured their continuity in nearly the same form. These three pivotal letters are:

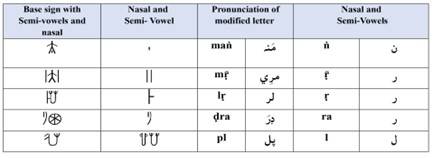

The Etruscan script, which underpins the development of the Roman script, and the Phoenician script, widely recognised as the foundation of all alphabetic systems, exhibit notable similarities to the Indus script. Numerous scholars, including Reves and Doggumati, have recently explored these parallels in their research.

In the aftermath of the Mohenjo-daro excavations, Piccoli conducted pioneering efforts to decipher the Indus script by analyzing its symbols in comparison with those of the Etruscan script. His work underscored their remarkable resemblance. Examples of Etruscan symbols corresponding to the Indus script are provided below for further analysis.

Here are some similar symbols found in Etruscan and Phoenician scripts:

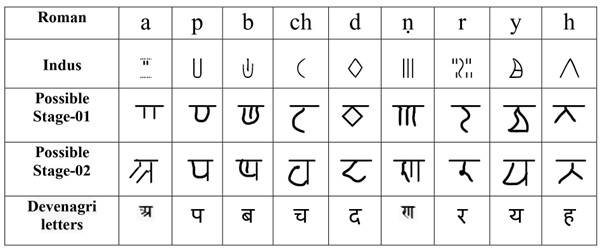

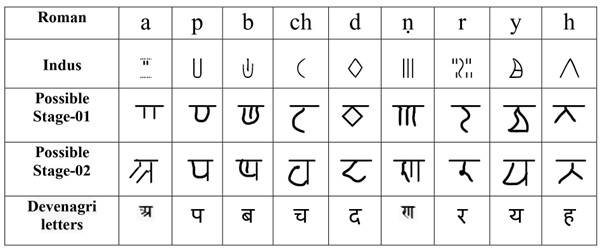

Influence on Devanagari

Some traces of the evolution of Devanagari from the Indus script, along with its possible evolutionary stages, are illustrated below. These findings strongly suggest that the origins of the Devanagari script may lie in Sindh, the Nagari script has retained nearly all the phonetic features of the Indus alphabet.

Note: 1) in Indus signs "y" and "r" are included vowel signs, examples of basic signs should be considered without them. 2) "ṇ" and "a" in Devanagari are of archaic script.

Brahmi is widely regarded as the precursor of all suBContinental alphabetic scripts. However, when examining Brahmi characters, it becomes evident that the Indus script shares a closer relationship with Devanagari than with Brahmi, indicating a direct connection between the Indus script and Devanagari.

While the origin of Brahmi is generally traced back to the Indus script—a view widely accepted by scholars—it is also occasionally linked to Aramaic and Phoenician scripts. In both scenarios, Brahmi remains directly or indirectly connected to the Indus script.

The Indus script directly influenced Brahmi, particularly in its method of connecting vowels with consonants and linking consonants with other consonant signs. If we consider this characteristic in Brahmi, the number of its letter signs would expand into the hundreds, similar to the Indus script.

This raises an important question: does the abundance of signs in Brahmi negate its status as an alphabet? Such observations suggest that the emphasis on the multiplicity of signs in the Indus script may be unwarranted. This feature of Brahmi also sheds light on the possible processes and structural principles underlying the Indus script.

The following is the procedure for connecting vowels in Brahmi script:

As to the conjunction of consonants with consonants in Brahmi and the corresponding new sign:

Influence on the Roman script

Historically, there is little evidence to establish a direct similarity between the Roman and Indus scripts, apart from the "Etruscan" script, whose symbols show a notable correspondence with the Indus script. While certain features of the Abugida script are present in the Indus script, its overall usage characteristics align more closely with those of the Roman script, particularly when Indus symbols are used individually without conjunctions.

When examining Roman signs, they often appear identical or remarkably similar to those of the Indus script. The most striking feature is the basic structural integrity of the signs, which the Roman script seems to have preserved over time.

Indus Alphabet

The most important and distinctive feature of the Indus script lies in its unique sounds, whose origins have remained buried within the land for thousands of years. No other language in the world can credibly claim this script as its own, except Sindhi. This uniqueness stems from its characters and phonetics, which are unparalleled.

These features strongly support the idea that Sindhi could be the progenitor of hundreds of languages, while it remains implausible for any language to claim that Sindhi is its offshoot. Sindhi stands as Prakrit—the natural language—emerging organically from the very land it inhabits.

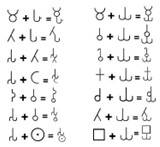

Here are the vowels in the Indus Alphabet:

Here are the consonants in the Indus Alphabet:

42 letters except "ع" and "ئـ", but another variant of "ś" which is common in Sanskrit but has been deleted from Sindhi.

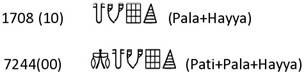

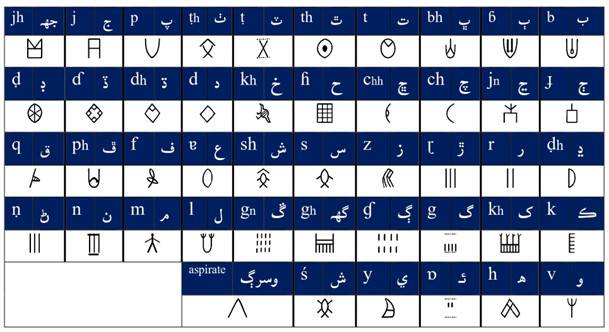

What secrets do the seals reveal in the light of the Indus alphabet:

A brief overview of the Sindhu Prakrit script has been provided above, based on derived characters and established principles of the script. Using this framework, selected seals from the Indus Valley Civilisation are analysed, addressing key questions about its founder, language, and political, social, religious, and cultural characteristics. With this alphabet as a guide, deciphering the seals should not pose significant challenges for scholars.

Several seals have already been analysed in detail in various articles. However, the comprehensive study of all seals, including their linguistic and historical examinations, remains an ongoing endeavour. The involvement of Sanskrit scholars is urgently needed to advance this work. Despite this challenge, preliminary findings will be shared with researchers soon to facilitate further progress.

It is anticipated that this research will inspire scholars to explore new directions, paving the way for in-depth investigations that could redefine our understanding of human history. These efforts may ultimately unlock the secrets of the Indus Valley Civilisation and its enduring legacy.

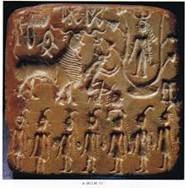

To begin, we address a fundamental question: what language was spoken in the Indus society during that time? In this regard, the reading of the selected seal presented above provides evidence that helps explain and confirm the language in use. A summary of the principles for interpreting the seals has already been outlined.

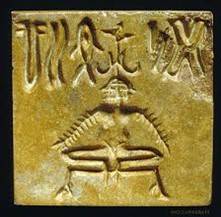

![]()

The inscription on the seal suggests that the prevailing language of the Indus Civilisation was Prakrit, a hypothesis that is not implausible. The Indus Empire covered an extensive geographic area, and it is reasonable to assume that regional dialects may have exhibited slight variations in tone or arrangement.

Among the languages most closely related to Sindhi are Gujarati, Rajasthani (or Marwari), and Saraiki, all of which share a common linguistic origin. However, the written language of the Indus Civilisation appears to have been uniform across its expanse, as evidenced by the seal inscriptions. Remarkably, Sindhi has preserved many of the linguistic qualities and characteristics observed in these inscriptions, as noted by scholars such as Ernest Trumpp.

“If we compare now the Sindh! with its sister-tongues, we must assign to it, in a grammatical point of view, the first place among them. It is much more closely related to the old Prakrit, than the Marathi, Hindi, Panjabi and Bangali of our days, and it has preserved an exuberance of grammatical forms, for which all its sisters may well envy it. For, while all the modern vernaculars of India are already in a state of complete decomposition, the old venerable mother-tongue being hardly recognisable in her degenerate daughters, the Sindhi has, on the contrary, preserved most important fragments of it and erected for itself a grammatical structure, which surpasses in beauty of execution and internal harmony by far the loose and levelling construction of its sisters.”

The notion that Prakrit predates Sanskrit is neither new nor surprising. Many theories propose that Sanskrit is a refined form of Prakrit, with numerous scholars presenting empirical arguments and evidence to support this idea. These conclusions align with fundamental linguistic principles. However, some scholars from both the West and India reject this realistic hypothesis, instead proposing the unfounded claim that all languages are derived from Sanskrit. Such arguments often ignore basic linguistic principles and rely on artificial logic.

The theory suggesting that Prakrit evolved from Sanskrit lacks robust linguistic evidence and fails to meet key criteria for such a transformation. When analysing sounds and phonetics, particularly in the case of Sindhi, the so-called "daughters" of Sanskrit often appear richer and more substantial than their "mother."

In the 19th century, Western scholars popularised the Aryan invasion theory, which gained significant academic traction. As a result, the Dravidian theory emerged as a prominent explanation for the language of the Indus society, drawing on the ancient heritage of the Tamil language. While this idea aligns with certain historical realities, it is important to consider that Prakrit, having undergone its earliest evolutionary processes, may have been the first language to attain the status of a fully developed linguistic system. Prakrit likely served as the clerical, ritualistic, administrative, and political language of a vast empire, achieving a level of perfection unprecedented at the time.

The name "Sindhu" is deeply connected to this linguistic heritage and its historical context. The influence of Sindhu Prakrit is evident not only in Indo-European languages but also in Semitic and Dravidian tongues. Even before the dawn of civilisation, the relationships between early languages spoken by nomadic tribes in Central Asia, Iran, and India were shaped by their interactions with Sindhu Prakrit. According to evolutionary principles, Sindhu Prakrit must be the first language to reach a high level of development, making its position central and dominant in linguistic history.

One of the most compelling aspects of Sindhu Prakrit is its unique phonetics and sounds, which demonstrate that Sindhi cannot be derived from any other language. This distinctiveness positions Sindhu Prakrit as the foundation of Indo-European languages and the progenitor of their linguistic family. A thorough examination of linguistic principles, underpinned by the evidence of seal readings, has the potential to clarify unresolved questions about language evolution. Unfortunately, this area of study remains underexplored and requires further research to achieve definitive conclusions.

This brief review focuses on insights gleaned from the seal reading and does not provide a comprehensive discussion of the evolution or origins of the Sindhi language, which would require more extensive analysis. Nevertheless, it aims to draw the attention of linguistic scholars to key issues, such as the etymological roots of Sindhi words that begin with the implosive "B (ɓ)" sound, which remain beyond the reach of European linguists. Words like "burn" and "bi-" exemplify this phenomenon, highlighting the need to grant Sindhi the scholarly recognition it deserves to fully uncover its linguistic significance.

The extent of the Indus society and its founders

One of the most debated questions among researchers and experts for over a century is the identity of the originators of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Historical evidence points to the existence of ancient Aryan empires beyond the suBContinent, spanning regions such as Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East. Based on various testimonies, historians have attributed the foundation of the Vedic civilisation, which succeeded the Indus civilisation, to the Aryans who migrated to the suBContinent.

This narrative, however, has been contentious and politically charged. The rise of German ethnocentrism further complicated the discourse, creating a confusing and divisive academic landscape. The emergence of the Indus civilisation should have prompted a re-evaluation of earlier assumptions, particularly the idea that the Vedic civilisation might represent a continuation rather than a replacement of the Indus civilisation. Unfortunately, political biases prevented such a shift in perspective. However, in recent years, the theory of Aryan migration has gradually lost credibility and popularity, with new evidence challenging its foundations.

If the Aryans who settled in Anatolia were proportionally integrated into the Indus civilisation's vast population, their demographic contribution would have been relatively minor, comparable to a small province or state within the larger Indus domain. Even if they had invaded and ruled for centuries—similar to the Arabs or Persians in later history—their presence would likely have faded over time, much like the influence of those later conquerors. Yet, the Aryans are uniquely credited with an improbable feat: the supposed displacement or erasure of the entire Indus population, leaving no trace of continuity. This "miracle" is both implausible and unsubstantiated.

It is puzzling why some Western scholars appear to overlook or undervalue the significance of "carbon dating" in their historical analyses. For centuries, the Sumerian civilisation has been regarded as the oldest known civilisation. However, the seals of the Indus Valley Civilisation present evidence that challenges this long-standing assumption.

The foundation of Sumerian civilisation rests on the worship of the god "An" and the associated pantheon of deities known as the "Anunnaki." These figures are central to Sumerian philosophy, religion, and belief systems. Intriguingly, these deities correspond to the secondary or middle period of the Indus civilisation, suggesting a more complex and interconnected narrative than previously acknowledged.

This alignment of religious and philosophical elements warrants further investigation, particularly in light of the evidence provided by the Indus seals. Such findings could reshape our understanding of the chronological and cultural relationship between the Indus and Sumerian civilisations.

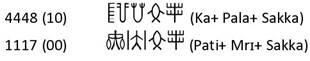

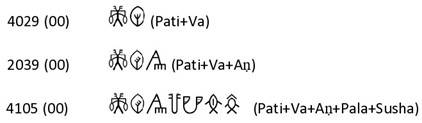

To substantiate this claim, the following selected seals from the Indus Valley Civilisation are presented, which reveal traces of the deity 'An.'

As per the practical Sanskrit-English dictionary:

Va: Name of Varuṇa

Aṇa: To salute (respectfully), bow down to

Pāla: A protector, guardian, keeper, a king (Shabda-Sagara)

Suṣā: A city of Varuṇa (The Purana Index)

According to Sanskrit dictionaries, the first Text, "Va," represents the name of the god "Varuṇa." In the second text, "Aṇ" is attached to "Va," that also signifies "honorable" or "noble." The name "Varuṇa" is thus derived from the combination "Va-Aṇ," where "Aṇ," rendered as "An," holds significance in the Sumerian civilisation, forming the cornerstone of its philosophy and cultural framework.

The third Indus text further elucidates that "Aṇ" or "Varuṇa" was not only a prominent figure in the ancient Elamite civilisation, ruling the city of "Susha" (present-day Susa in southwestern Iran), but he also emerged as a highly revered deity or avatar of his time. The remains, bearing the same name to this day, preserves remnants of the Elamite civilisation dating back to 2800 BC. This civilisation, closely associated with Vedic traditions, provided a foundation for the Avesta and played a pivotal role in shaping ancient Iranian ideology. The connection between Lord Varuṇa and the city of Susha is explicitly mentioned in Vedic scriptures. Parpola also highlighted the association between the deities Varuna and An, arguing that Sumerian culture influenced Vedic culture concerning this deity. However, the evidence indicates that the influence was, in fact, the reverse.

Scholars such as Hunter, along with others, have highlighted the parallels between the symbols of the Elamite script and the Indus script. A recent paper by Phul provides further insights into this association.

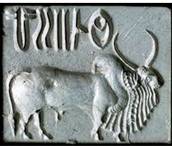

These findings suggest that the Sumerian civilisation, often regarded as one of the earliest advanced civilisations, was fundamentally influenced by the Indus civilisation. During the peak of the Sumerian era, the Indus civilisation was already well-established, with its roots tracing back to an even earlier period. Similarly, the traditions of the Rigveda predate the era of Mohenjo-daro, serving as a cultural and intellectual catalyst for the rise of the Indus civilisation. The Rigveda's early and foundational texts, referred to as "Parasuṭra" or "Para Sutra," are reflected in the evidence provided by the following Indus seal.

![]()

Sūtra: 1. A thread in general. 2. A rule, a precept, in morals or science; a short, obscure, and technical sentence, enjoying some observance in law or religion, or intimating some rule in grammar, logic, &c.; in each case it is the fundamental and primitive part of Hindu learning, and is the form in which the works of the early and supposed inspired writers appear; the ingenuity and labour of subsequent authors having expanded and explained the original Sutras in various commentaries and glosses. 3. An opinion or decree, (in law.) 4. A string, a collection of threads, as that worn by the three first classes, &c. 5. The string or wire of a puppet. 6. A fibre. E. ṣiv to sew, ṣṭran Unadi aff., and iva changed to ū; or sūtra to string, ac aff. (CDSD-Shabda-Sagra)

Sūtra: has the sense of ‘thread’ in the Atharvaveda and later. In the sense of a ‘ book of rules ’ for the guidance of sacrifices and so forth, the word occurs in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad (Arthur et.al 1912)

It is worth noting that some authors have attempted to associate the "Anunnaki gods" with extraterrestrial beings or "aliens."

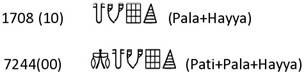

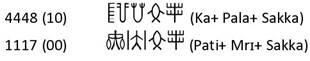

Who were the rulers of the Indus Empire during its zenith? This question is of significant importance and must be addressed through the evidence found in the ancient Indus texts. To explore this, specific seals inscribed with relevant texts have been selected. Notably, all these seals, which exclusively belong to the remains of the ancient Indus site of Mohenjo-daro, are made of copper. This unique characteristic underscores the importance of the inscriptions and reinforces the significance of their meaning. Moreover, the presence of such seals strongly supports the conclusion that Mohenjo-daro was the capital of this vast and influential empire. Textual references for this analysis are drawn from Mahadev's book.

Haihaya: Name of a race (said to have been descendants of Yadu; they are described in the Purāṇas as separated into 5 divisions, viz. the Tālajaṅghas, Vīti-hotras, Āvantyas, Tuṇḍikeras, and Jātas; they are, said to have overrun parts of India along with the Śakas or Scythian tribes (Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary)

Name of the great-grandson of Yadu. Name of Arjuna Kārtavīrya (The practical Sanskrit-English dictionary)

The readings of the seals indicate that the ruling family of Mohenjo Daro belonged to the Haya Dynasty, descendants of Yadu, with Arjuna Kartavira recognised as a prominent ruler of this lineage. In Vedic literature and history, this era is described as remarkable and grand, often praised to such an extent that some scholars dismiss it as mythological. This scepticism stems from the prevailing academic consensus that the Vedic period in India began around 1700 BC, with no records of such rulers in Syria, Iran, or Central Asia. Furthermore, while some scholars resist acknowledging the existence of the Vedas predating or contemporaneous with the Indus Valley Civilisation, significant historical narratives, such as "Aryavarta" and the "Bharta Dynasty," remain historically ambiguous. As a result, many historical accounts from this era are regarded as speculative rather than definitive.

Although a comprehensive history of the second millennium BC remains elusive, fragmentary evidence has been uncovered. The concept of "Aryavarta" does not find corroboration in the historical record, as the "Hitti Arian" and "Mitanni Arian" are documented to have ruled outside the suBContinent during and after 1800 BC. However, the readings of the Indus seals unequivocally reveal the rulers of the Indus Civilisation. Based on these findings, it can be confidently asserted that the Indus Civilisation represented "Aryavarta," an empire whose influence extended across the ancient world, with Mohenjo Daro serving as its central hub. Supreme authority rested directly or indirectly with this centre.

The "Great Flood," likely occurring between 2300 and 2200 BC, is believed to have brought this vast empire to an end through natural disaster. The Aryans subsequently played a foundational role in shaping early Iranian history through the Elamite Civilisation and likely contributed to the development of Sumerian and possibly Egyptian civilisations. Following the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilisation, Aryan tribes, already governing limited territories across Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Arabian Peninsula, went on to establish independent states.

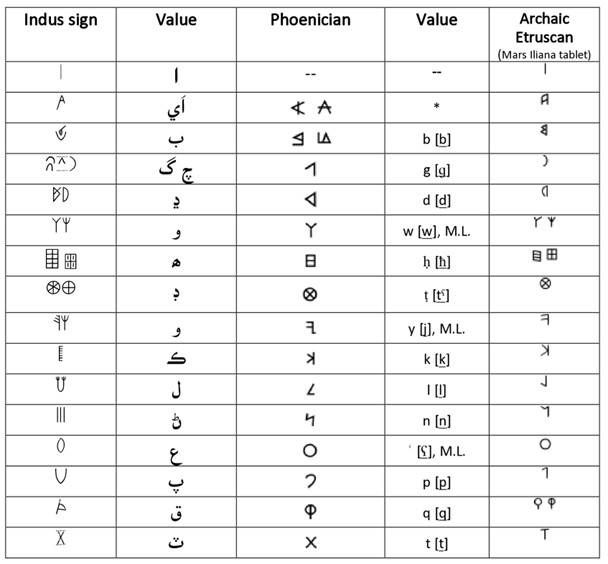

Evidence from the Indus texts provides compelling examples of the presence of Aryan tribes within the Indus Valley. These texts serve as clear proof of the civilisation’s extensive reach and influence, underscoring its historical significance.

'The religion of the early Iranians of the Saka branch coming to Central Asia around 1500 BC /It is clear that Proto-Saka *dasa, “man,” is the etymology of the ethnic name which in Old Persian appears as Daha-, for many ethnic self-appellations go back to words with this meaning; for instance the native ethnic name of the Mari, who speak a Uralic (Finno-Ugric) language, goes back to Proto-Indo-Aryan *marya-, “man” (literally “one who has to die, mortal”)' (Asko Parpola)

Seals bearing Indus inscriptions have been discovered in all the mentioned regions except Egypt, revealing insights that extend far beyond simple trade relations. Despite repeated repopulations in areas such as Mesopotamia and Iran, a significant number of seals provide compelling evidence of sustained interactions. If the seals unearthed in Lothal are interpreted as evidence of it being a settlement within the Indus Valley Civilisation, why are the seals found in Elamite territories, Sumer, and the Amu Darya region (modern Uzbekistan) often dismissed as mere indicators of trade relationships?

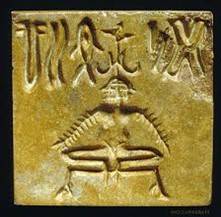

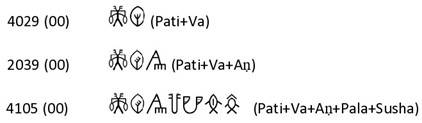

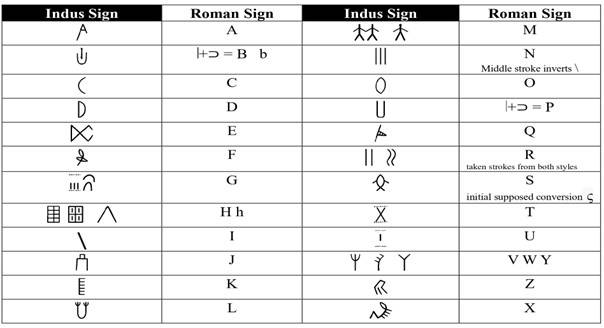

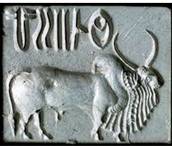

![]()

The term mukuTa (also spelled makuṭa) refers to a crown, diadem, or tiara, often described as crescent-shaped in contrast to other headgear like the kirīṭa, which is pointed, and the mauli, which has three points. It can also denote a crest, peak, or point, and in some contexts, it serves as a proper noun, particularly in reference to places or individuals (derived from Rāja-mukuṭa).

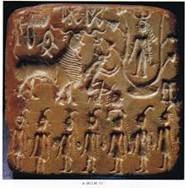

The reign of the Haya Dynasty unveils the original name of Mohenjo Daro as 'Maheshmati' with the elephant serving as the symbol of governance. This emblem is evident in the seal referenced above. The inscription on the seal indicates its royal purpose, while the three-pronged crown on the elephant's head symbolises the crown holder of that era. Further clarity is provided by another seal, which depicts a similar crown atop the head of a man seated with legs folded and arms outstretched in prayer before a deity, accompanied by the seven supreme rishis. The inscription on this seal reads 'pa su ayati,' translating to 'stretching out hands in prayer to Mahadev’.

![]()

Basic Beliefs of the Indus Civilisation

The religious practices of the Indus Civilisation have long been a subject of scholarly inquiry and debate. One prominent topic of discussion is the interpretation of a yogic postured figure depicted on an Indus seal, often identified as a proto-Shiva figure. Beyond this seal, numerous artifacts and historical contexts attest to the ancient origins of Mahadev Shiva's veneration and his profound connection to the foundational beliefs of Indus society, a relationship extensively explored in academic literature.

This discussion highlights a specific region in Sindh, notable for its historical and cultural significance, where names and traditions are deeply associated with Shiva. The Gorakh region and Manchhar Lake in the Khirthar Valley, extending to the Hinglaj region, serve as a remarkable backdrop to ancient legends involving the divine couple, Shiva and Parvati. These areas, recognised as the ancient abodes of Shiva, are traditionally regarded as the cradle of early knowledge and enlightenment.

The Indus Civilisation is believed to have originated along the banks of Manchhar Lake and the Khirthar Valley, where the first organised settlements emerged under the aegis of Mahadev Shiva. The etymological roots of place names such as "Shiv+asthan" or "Shiv+vahan," evolving into "Sivestan" or "Sevhan," further underscore Shiva's centrality. Certain interpretations of Indus seals suggest that the major cities of the Indus Valley were named after epithets of Shiva, a subject for further exploration in subsequent studies.

Names such as Adinath, Adi Jogi, and Goraknath highlight Shiva's integral role across religions originating in the suBContinent, including Jainism, while also linking the beliefs of the West and the Middle East to this region. For instance, the name "Yehva," with origins traceable to Vedic scriptures, reflects these connections. The antiquity of this civilisation predates Mohenjo-Daro's zenith by several millennia, possibly exceeding 3,000 years. It is said that this was the land where the first seven Param Rishis attained enlightenment under their initial guru, aligning with the socio-geographical contexts described in the Rigveda, where yoga and Sanyas (renunciation) were first established.

The marriage of Mahadev Shiva, the groom of Lahut, and Mata Parvati, the bride of Hinglaj, symbolises the genesis of a lineage that significantly shaped global spiritual traditions. Yoga and meditation, pioneered here, not only enhanced physical and cognitive abilities but also laid the foundation for early medical practices, marking the inception of (Vejj) medical sciences. Parvati, revered for her expertise in herbal remedies, played a pivotal role in these early advancements. Indus seals prominently display imagery reflecting the couple's healing attributes, as detailed in the article “Sindhu Prakrit Unveils the Enigma: Revealing the Origins of Ayurveda.”

The development of sciences and the establishment of Sanatana Dharma also trace their roots to this region. Oral traditions (shruti) eventually necessitated the creation of the world's first script—the Indus script—which catalysed the emergence and evolution of one of the world’s earliest civilisations.

Contrary to the later association of Mount Kailash with Mahadev Shiva—popularised during the British era, as noted by Alex Mackay—the historical and spiritual significance of Manchhar Lake (Mansara) and Gorakh predates this period. Taj Muhammad Sahrai, in his works, recounts the tradition of Prophet Mani, accompanied by his father Patak and Amu, traveling through Sindh, including Manchhar Lake, where rituals of general ablution were performed by devotees. Furthermore, the association of Gorakh with Shiva is evidenced in the practice of applying ashes of cow dung, a tradition deeply rooted in historical and spiritual narratives.

The Disappearance of the Indus Civilisation

A crucial and enduring question in the study of the Indus Valley Civilisation is how it vanished without leaving any definitive trace. While the interpretations of seals provide some insights, the circumstances surrounding its decline merit detailed examination.

The Indus Valley Civilisation reached its peak around 2600 BC, but its decline is believed to have been caused by a catastrophic natural disaster known as the "Great Flood." According to David Wright, this flood occurred around 2348 BC. Before this time, the world outside the Indus civilisation lacked examples of organised, extensive governance or empires, including limited evidence of a structured political system in the Egyptian civilisation before 2600 BC.

The flood dealt a devastating blow to the Indus civilisation, destroying its foundational structures, including administrative, political, social, and economic systems. This disaster eroded the civilisation's central authority and marked the tragic demise of one of humanity's most remarkable legacies, referred to as "Aryavarta the Great."

In the aftermath of the flood, the region witnessed a series of conflicts and power struggles among Aryan tribes across the Indo-European region. This fragmentation led to the emergence of numerous independent kingdoms, both within India—such as those of the Kurus and Pandavas—and outside, including the Mitanni and Hittites. In the heartland of the Indus Valley, a smaller state known as Sindhu Desh emerged, its boundaries resembling those of Sindh during the reign of Raja Dahar. This state preserved aspects of the Indus society until approximately 1900 BC.

Subhash Kak and other scholars have employed astrological methods to estimate three potential dates for the Mahabharata war. One of these dates, falling between 1900 and 1850 BC, aligns most closely with existing chronological frameworks. This era marked significant transformations in the region. The defeat of Sindhu Desh altered the economic, religious, social, and political landscape, shifting the balance of power to new centres, such as the Rakhi Garhi region, considered the seat of the Pandavas. The population distribution also changed, reflecting broader societal shifts.

One of the most profound changes during this period was linguistic. Sindhu Prakrit evolved into Sanskrit, and Sanatana Dharma underwent significant transformation, ultimately giving rise to modern Hinduism. This new religious framework diverged from the earlier Vedic Dharma, as scholars like Asko Parpola have noted. Additionally, Grierson observed that the Bharata dynasty excluded the northwestern regions from Aryan civilisation, branding them as barbaric. This marginalisation obscured the historical roots of the Indus Valley's legacy, a common practice of dominant empires seeking to assert their authority over predecessors.

Despite this historical erasure, the seals and artifacts buried within the Indus homeland hold immense significance. They remain a potent testament to the grandeur of this early civilisation, capable of reshaping our understanding of world history.