Much has been written about the effects of colonisation on native populations. Generally, such accounts are one sided. Some writers condemn colonial rule and leave no room for appreciation of some of the rare and good things done by the colonists. On the other hand, there are apologists who tend to present colonial rule in favourable light.

Colonists came to foreign lands for one and only one reason: to exploit the natural resources of the occupied lands. In the process of dismantling the old order in occupied hands they also instituted some reforms.

In the case of India, the British brought some reforms. They gave India an extensive network of railways, instituted land revenue system and initiated western education that brought study of science into schools and colleges. But these measures pail when compared to the long-lasting devastating effects on the land and its people.

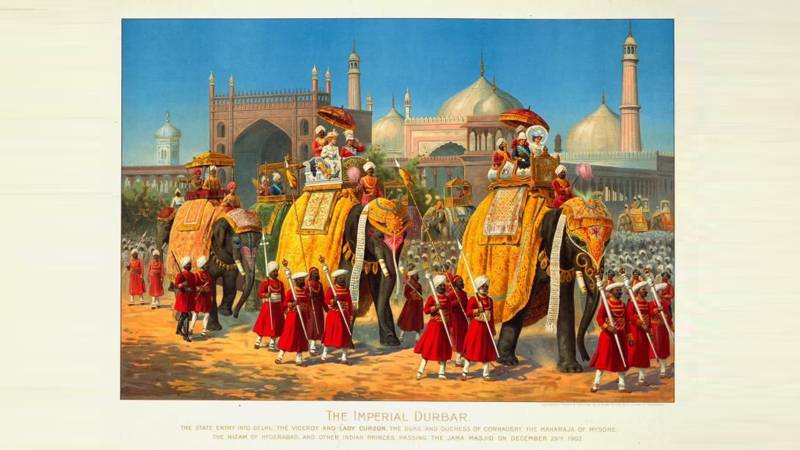

In India, the British came as traders and gradually increased their influence and power to the point that by the mid-1800s the traders’ company – the East India Company – was running large swathes of India with its own army and administrative staff.

New research by Indian economist Utsa Patnaik puts to rest the notion that India was a financial burden on the British Empire. On the contrary, India was the source of riches that were systematically exploited for the benefit of Great Britain. Drawing on 200 years of detailed data on tax and trade, Patnaik concluded that Britain siphoned off nearly $45 trillion from India during a period from 1765 to 1938. It has also been said that Indian wealth built the magnificent Westminster Palace that includes the parliament building and Big Ben on the Thames River.

When the British arrived in India, its GDP varied between 25% and 35% of the world’s total GDP. It was bigger than the total GDP of Europe. When India was granted independence in 1947, its GDP had fallen to a dismal 2%.

Economic exploitation aside, it was the cultural exploitation of the Indian people that had a long-lasting negative effect.

In India, the British positioned themselves as rulers as well as saviours. They brought with them the fruits of Industrial Revolution and emphasised that native stuff was much inferior to the imported British stuff. Along with material superiority came a sense of cultural superiority.

Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800 to 1859 AD) was a British politician who was convinced of the superiority of English culture, language and education and did not mince any words advocating their superiority. He served in many administrative positions in India and was considered the architect of education system of India. He also said that the British should concentrate of a small number of natives who would still look natives but because of British education will not think like Indians. He was so dismissive of Indian accomplishments that he confidently proclaimed that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia. It was the Victorian civilising mission that gave us Kipling’s famous phrase that natives were the white man’s burden.

Willian Dalrymple is a Scottish historian who has written best seller books on different eras of Indian history. His recently published book The Golden Road (Bloomsburry Publishers, 2024) deals with ancient history of India and it is awesome.

He writes, “For a millennium and a half, India was a confident exporter of its diverse civilisation, creating around it a vast empire of ideas. Indian art, religions, technology, astronomy, music, dance, literature, mathematics and mythology blazed a trail across the world, along a Golden Road that stretched from the Red Sea to the Pacific.”

William Dalrymple draws from a lifetime of scholarship to highlight India’s oft-forgotten position as the heart of ancient Eurasia. He mentions the largest Hindu temple in the world at Angkor Wat in modern-day Cambodia, to the Zen Buddhism of Japan, from the trade that helped fund the Roman Empire to the creation of the numerals we use today (including zero). India transformed the culture and technology of the ancient world – and our world today as we know it.

In an interview, Dalrymple said that the British went to India, conquered it and dismissed it as a barbaric civilisation. Macaulay’s dismissive remarks lingered in the minds of the colonial administrators and helped shape the racist policies towards the natives. Those views were prevalent not only through duration of the Raj years, but lingered on long after the colonists had quit India.

In 1938, my birth year, the British had been in India for over 150 years and on the western frontier for nearly 90 years. After independence, in 1947, the Peshawar Garrison Club, a bastion of British culture, did not change. The cultural metamorphosis that we in undivided India were subjected to remained visible and palpable for a long time after the colonists had left.

In the 1970s, when I went back to Peshawar to teach at Khyber Medical College, we took out family membership at Peshawar Club. One Sunday, I took my American wife and two children for tea. The waiter took our order, came back and presented me an envelope in a small silver tray. It was a typed note from secretary of the Club, drawing my “kind attention to the dress code of the Club.” I had gone to the Club wearing Pakistani clothes. 25 years after independence, the winds of change had not entered the rarefied and racist atmosphere of the Club. It is funny that my wife was dressed in Pakistani clothes but was not refused service. I guess the skin colour still mattered at Peshawar Club, for within the confines of the Club, she was still considered a memsahib. One other time I was refused service at the Club, while my wife and children were served. Instead of making a scene, I opted to have refreshments in the parking lot of the Club.

On the road to Agra, a moustached elderly man wearing a faded red uniform came to me, and in a low voice, asked if I would let the "Sahib loog" get their lunch first. For him, it was improper that one of his kind was ahead of the white people in lunch line

When I was on the faculty of Khyber Medical College, a majority of teaching faculty would come to the college and hospital in Western clothes. In 1971, Maulana Mufti Mahmud, Ameer of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (father of the present day Maulana Fazal-ur-Rahman), became chief minister of KP province. He ordered that henceforth all government employees would come to work in native clothes. This created a hilarious situation. Some professors showed up in shalwar and bush shirt. The tailors had a field day in churning out desi clothes for officers and professors.

Earlier, I had been politely asked by the Superintendent of Lady Reading Hospital to refrain from wearing native clothes while making evening rounds at the hospital. But when the chief minister ordered all of us to wear native clothes, I rebelled and resorted to Western clothes. The poor superintendent did not know what to do with me!

The chief minister was admitted with uncontrolled diabetes. His physician Dr Ali Raza saw the opportunity to influence the chief minister’s decision. Dr Raza pleaded that because of ‘hygienic’ reasons, doctors should be exempted from wearing native dress at work. Dr Raza told him that shalwar-kameez are not very conducive to containing infections and physicians are liable to spread disease from patient to patient. It was frivolous reasoning, but chief minister, perhaps still in diabetic crises, ordered an exemption for doctors. I think you will guess right if I tell you that the next day the faculty showed up for work in their Western suits, but to the chagrin of the medical superintendent, I chose to come in shalwar-kameez. In civilian life, how we dress is a personal choice.

In India and Pakistan, many generations of educated people grew up maintaining a distance from their own language and culture. And they always glorified British culture and English language. Psychologically, we were made to believe we were inferior to our colonial masters.

About 35 years ago, I was on a tourist bus going to Agra from Delhi. I was the only desi among the busload of white foreigners. On the way, we stopped at a rest house for lunch. We all made a line to the buffet table. As the line was slowly moving, a waiter kept looking at me. He was a moustached elderly man wearing a faded red uniform and a military style cap. Finally, he came to me, and in a low voice asked me in Hindi if I would let the "Sahib loog" get their lunch first. For him, it was improper that one of his kind was ahead of the white people in lunch line. I felt sorry for him – that he was still frozen in an era that had long passed.

The apologists for colonial rule would point to the extensive infrastructure and other laudable reforms, but skip over the psychologic damage that protracted colonial rule caused in many generations of the people of the Indian Subcontinent.

Before closing, I must mention that a large number of British voluntarily came to India and Pakistan, and lived out the rest of their lives serving the common people.

Ms Margret Harbottle taught English at Peshawar University, Geoffrey Langlands served in the Pakistan Army, later taught at Aitchison College in Lahore and then ran a high school in the Wakhan Corridor in Chitral. The school bears his name.

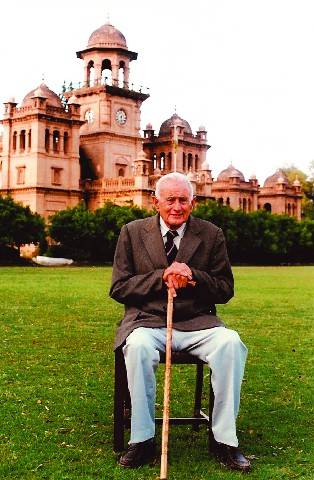

Legendary teacher and social worker Professor HM Close, photographed at his beloved Islamia College, Peshawar

Dr Norval Christie, an eye surgeon, served ordinary people at Taxila Christian Hospital and left a rich legacy of service.

And of course, my English teacher at Islamia College Peshawar (and later a friend), HM Close, who served the people of KP not only as a teacher but also as a generous financial supporter of children education, arranging surgeries for handicapped children, taking college students to the northern mountains for malaria eradication and much more. I wrote about his life and work in August 2021.

Such were the people, and there were many others like them, who helped redeem the name of Britain after the hurried retreat of the colonists from India in 1947.