“His nature is too noble for the world,

He would not flatter Neptune for his trident,

Or Jove for his power to thunder.”

Shakespeare (Coriolanus III, i, 254)

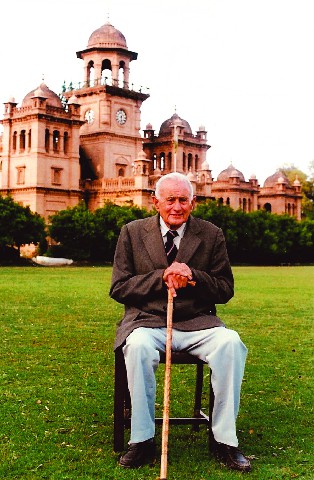

It was in 1953 that my path, that of a first-year college student, crossed with that of Mr. H. M. Close, the English professor at Islamia College. I write this essay to celebrate the gift of his life to the people of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. In his lifetime, the humble and soft-spoken Englishman touched and enriched hundreds and thousands of people. Mr. Close died in Peshawar in 1999.

Fresh out of Cambridge, Hubert Michael Close (because of the initials of his name, students affectionately called him Haji Muhammad Close) came to the Subcontinent in 1937 to teach at Saint Stephen’s College in Delhi. The Second World War took him to the African theatre of war where he commanded a Pathan company. After the war he returned to his teaching job at St. Stephen and made several trips to the Frontier to visit his former soldiers. During one of those visits in 1947, at the urging of Sir Olaf Caroe, the then British governor, he accepted a lecturer’s job at Islamia College. The love for the Pashtuns that he had felt while commanding a Pathan company along the shores of Mediterranean, now brought him to Peshawar to be amongst the people he so much loved and admired.

At Islamia, Mr. Close immersed himself in the college life in a way that was unprecedented. In addition to teaching a full complement of English courses, he oversaw college hostels as chief warden, conducted tutorials, oversaw the college library, organized sports, and of course, conducted the dreaded compulsory military training where he would force half-asleep students out of their warm beds on icy winter mornings for mandatory cross-country runs.

But his true legacy is his service to humanity. Here one sees his imprint not only on tens and thousands of students he taught, but also on the poor and the destitute people of Peshawar and beyond. There were handicapped children who received timely orthopedic care and became productive citizens because Mr. Close took them to the hospital for much-needed reconstructive surgeries. There are men and women alive today because Mr. Close donated his own blood time and time again – and for decades persuaded his students to help stock the blood bank at Lady Reading Hospital. There are many former criminals, now law-abiding and productive citizens, who were touched by his visits to the jail to look after their welfare. There are blind people who are a bit more independent today because Mr. Close helped procure books and other material for them. In ran all those errands riding a bicycle around the campus and the city.

In the mountains of Hazara there are people who were spared the ravages of smallpox and malaria because every summer Mr. Close led his students to those inaccessible areas to inoculate children and conduct anti-malaria spray. And then there are many natives who became educated because Mr. Close, in a most discrete way, paid for their education. He was an example of the noblest of the Christian tradition of serving others.

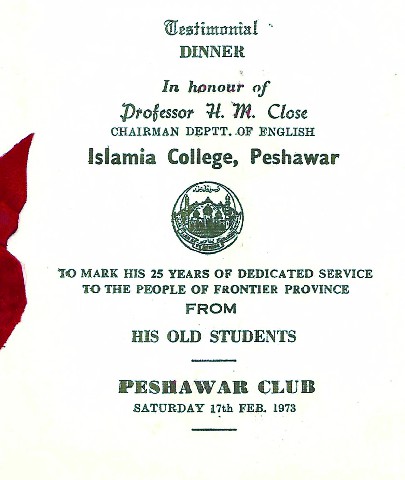

In 1972 a few of his former students; Dr. Shah Rukh Chughtai, Dr. Himayat Naqvi, Dr. Abdul Haseeb and myself organized a testimonial dinner to mark his 25 years at Islamia. Responding to a small advertisement in the newspaper, about 250 of his former students, a galaxy of the who’s who of KP and Pakistan travelled long distances to come to Peshawar Club to pay their tribute. He was visibly moved. It was the first time in 25 years that a group of his students had gathered to say a collective thank-you to him.

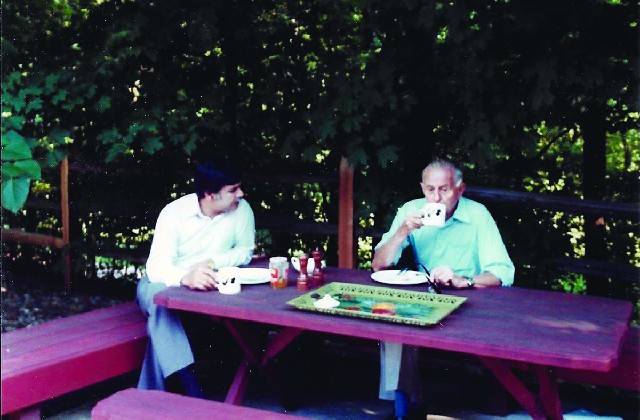

All the years that he lived in Peshawar, he would visit England every few years. During one of those visits in 1985, he instead came to America at our invitation. It was during that visit that I spent considerable time with him. We went to the Shakespearean Festival in Stratford, Canada - where he enjoyed attending a few of his favourite plays including the Gilbert and Sullivan’s opera The Pirates of Penzance.

Fresh out of Cambridge, Hubert Michael Close (because of the initials of his name, students affectionately called him Haji Muhammad Close) came to the Subcontinent in 1937 to teach at Saint Stephen’s College in Delhi

As we were driving back from Canada, I asked if he would consider writing his biography. He was not interested in my suggestion but was keen on having the manuscript of his book A Pathan Company published. (He had given me a copy of the manuscript in 1975). His biography, I reasoned, would be a composite history of Islamia College and the University of Peshawar because he was a close witness to the happenings on those campuses. In my view, only Mr. Close could write about the events with fairness and objectivity. Though he promised to think about it, he would not consider it seriously. On another occasion when I brought up the subject, he was more forthcoming in his reasons. He was reluctant because he could not write with candor and freedom about certain events and personalities. His faith and his good manners would not allow him to be unkind either in person or in print.

However, he went on to publish A Pathan Company in 1994 and in short time it went through four printings. Subsequently he published a long essay “Attlee, Wavell, Mountbatten and the Transfer of Power” in a book form in 1997. He was convinced that appointment of Lord Mountbatten as the last Viceroy of India was disastrous and that the independence of India and Pakistan would have been more fare and bloodless under Wavell. I wish I had been more persuasive regarding his biography.

During the same visit to America, we talked about other things as well. I asked him the reasons he had remained a bachelor. That was the only time I saw him lose his temper. He wondered as to why people do not pose the same question to Mian Majeed (another confirmed bachelor on the campus of Islamia). I apologized for asking a personal question and he in turn apologized for losing his cool. He confided that early on he had decided to put his personal needs on the side and that included having a family. Later he did change and adopted Sahar Gul, an Afghan boy, and lived out his old age surrounded by his adoptive son and his son’s growing family.

He was a deeply religious man but showed unrestrained respect for other faiths. He was the only teacher on the campus who would stop his lecture when the muezzin called for prayers from the college mosque and would remain silent for the duration of the call. He was a good example of what George Santayana, the American philosopher said, “Religion in its humility restores man to his only dignity: the courage to live by grace.” He was what Prophet Muhammad (may the peace and blessings of Allah be upon him) had characterized a righteous man:

The best richness is the richness of the soul

The best provision is piety and

The most profound philosophy is the fear of God.

I had often talked to him about his legacy. He was disappointed in the decline of educational standards, the breakdown of societal norms and rise of religious intolerance. He thought the teachers, including himself, had failed this society. His spirits would buoy, but only for a short time, by my argument that his legacy lives on in the success of thousands of his students. He would not discount individual successes but was disappointed that his former students did not exercise collective influence to bring about positive changes in the society. And in all our discussions spanning four decades I never heard him complain about his personal needs or wants. He was content whether he lived in the warden’s flat at Hardinge Hostel at islamia, in his bed-sitter above the canteen at Edwardes College or in a tiny two-room quarter on the premises of the same institution where he lived with his adopted son Sahar Gul and his family.

Ever since his retirement from Islamia, the college and the university authorities had adopted a neglectful attitude towards him. A one-time offer to provide him with free accommodation on the university campus, as the university had done for a few other retirees in the past, was unceremoniously withdrawn. It was disgraceful that successive vice chancellors, most of them his former students, did not pay any attention to his welfare.

I had often talked to him about his legacy. He was disappointed in the decline of educational standards, the breakdown of societal norms and rise of religious intolerance. He thought the teachers, including himself, had failed this society

On the contrary, some of his students in high government positions did help. The names of former chief secretaries of KP Sahibzada Imtiaz, Azam Khan and Ejaz Rahim and former inspector general police Dil Jan Khan come to mind. I am sure there were many others as well. (The University of Peshawar could redeem itself by naming either the International Hostel or the Tribal hostel after him.)

In 1984 the Queen conferred the title of Officer of the British Empire (OBE) on Mr. Close. There is an interesting story behind the award. A few years earlier the Queen’s birthday list had included a maid at Buckingham Palace. One of Mr. Close’s former students got so incensed he wrote a nasty letter of protest to then prime minister, Margaret Thatcher. In the letter he stated that while the British made a hurried and ignominious retreat from the Subcontinent in 1947 there were a handful of Englishmen and womenwho stayed behind to redeem the good name of England. It was a disgrace, the letter went on to say, that Great Britain took more pride in her singers and in her domestic servants than in the lives of people like Mr. Close. The writer received a polite reply through the ambassador of Great Britain stating that his letter would receive due consideration from Her Majesty’s Government. And it did.

In the same year, 1985, Pakistan followed suite and conferred Sitara-e-Imtiaz on Mr. Close. When he was presented to President Zia-ul-Haq for investiture, the president remarked that he knew Mr. Close rather well from his student days at St. Stephen College in Delhi. Despite a photographic memory and his penchant for remembering names, Mr. Close did not remember the future president as his student at St. Stephen.

In later years, he was getting more nostalgic about England. He would talk longingly of England and wanted to spend last years of his life there. He had at one time planned to live in the Old Boys’ hostel at Cambridge. Earlier in his life, when he would visit England to see his relatives, he would long to return to Peshawar. As he grew older, it was the pull of England that tugged on him. In the end he decided to stay in Peshawar amongst his adopted family. Those of us who have lived a better part of our lives in another country can relate to that inner feeling. Daud Kamal, one of his students from Islamia and later chairman of the Department of English at the university, wrote in one of his poems:

Anchor your dreams neither in the stars, nor the sea

But in the earth

Where ancestral dust sharpens the taste of ultimate sleep

So, it was no surprise that he wished to be returned to England upon his death.

Whenever I listened to The Last Farewell, a song by English singer Roger Whittaker, I always thought of Mr. Close. The song expresses, in words and music, the struggle of an Englishman as he bids farewell to his adopted land. When I heard the news of Mr. Close’s passing, I listened to the song again with moist eyes and heavy heart:

There is a ship lying ready in the harbour,

Tomorrow for old England she sails,

Far away from your land of endless sunshine,

To my land full of rainy skies again.

I shall be abroad that ship tomorrow,

For my heart is full of tears, it bids farewell.

For you are beautiful,

And I have loved you dearly,

More dearly than the spoken words can tell.

Dr. Sayed Amjad Hussain is an emeritus professor of surgery and an emeritus professor of humanities at the University of Toledo, USA. His is also an op-ed columnist for the daily Toledo Blade and daily Aaj of Peshawar. He may be reached at aghaji3@icloud.com