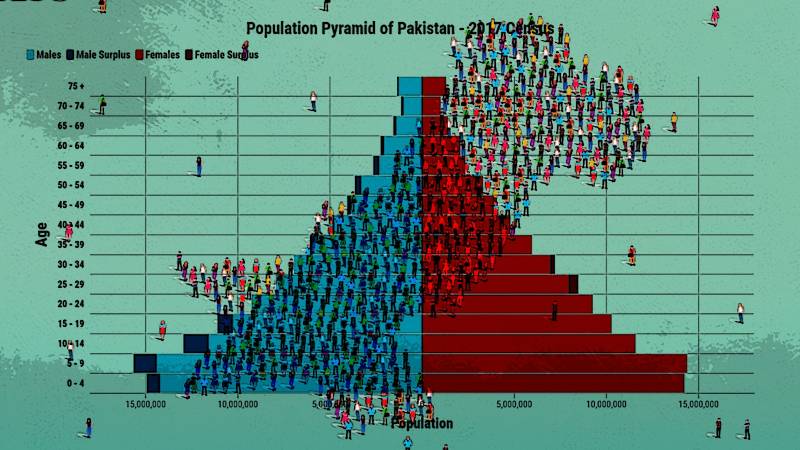

Pakistani society is experiencing an advantage in demographic terms that economists dub the “demographic dividend,” a phenomenon which is often described as a double-edged sword. A State Bank of Pakistan document describes Pakistan’s demographic situation in the following words, “In 2021, (Pakistan’s) growth rate was 1.9 percent, second only to Nigeria. Owing to this, Pakistan has a large young population where about 37 percent and 67 percent are less than or equal to 14 and 30 years, respectively. However, this also provides the country a unique opportunity for economic growth and development in what is called the demographic dividend.”

This advantage is a double-edged sword, because if we as a society succeed in providing these young people with jobs, our economy will get a boost. But if we fail to expand the economy at a rate which can facilitate the accommodation of this number of young people in our economy, it can become a great burden on our economy. This can result in social and political unrest, a rise in the crime rate and increased social and political tensions in society. The demographic dividend is not something which is going to affect us in some distant future. It is happening right now.

"Pakistan is going through a phase of demographic transition, experiencing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity of reaping the demographic dividend as the working-age population bulges and the dependency ratio declines,” said Durre Nayab, a joint director at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, a research institute and public policy think-tank in Islamabad. Pakistani economists have been arguing that in order to reap the benefit of this demographic dividend, the government need to formulate policies “in education, public health, and those that promote labor market flexibility and provide incentives for investment and savings'' said an expert. "If they do not enter the labor force the very logic of demographic dividend is defied, but if they become economically active, it poses a big challenge to the country’s economy to provide them gainful employment." Pakistan’s economy is growing at a rate slightly above 3 percent, which means the economy will not be able to take advantage of this demographic dividend during the next decade.

Globally, the working age population is defined as all persons between 15-64 years of age. “Demographic dividend is a period of accelerated economic growth in a country stemming from a favorable age structure when the share of the working age population is greater than the share of the dependent population.” Three basic features of Pakistan’s political reality present major challenges. It is situated in an extremely tough neighborhood—in the West is militarily unstable Afghanistan, in the East is militarily threatening India. We cannot remain immune from superpower rivalry in the Indian Ocean as Iran-US tensions are a permanent source of instability in the region. Due to many years of mismanagement, our economy is in shambles. Our major political parties are at war with each other. And we have two insurgencies, one in the North West and the other in the South West.

With an annual growth rate of more than 2 percent, Pakistan’s population increase is not expected to stabilize in the next three decades, even if Pakistan were to put in place a successful population control policy.

In such a situation, who forms the government in Islamabad and provincial capitals should be the last question our political class should be debating in the media and the public space where political discourse takes place. But this is not the case: our whole political discourse revolves around the question of who will form the future government. They are fighting among themselves, insulting and demonizing each other in the process. But never for a minute do Pakistan’s politicians discuss such a potent economic advantage that is knocking at our door and how to make this more advantageous for the nation.

Our political class does not even bother acknowledging that this potential advantage is likely to transform into a major threat if we fail to provide jobs for our youth or if the economy doesn’t grow at a rate that could facilitate the accommodation of a large number of young people as productive members of society.

With an annual growth rate of more than 2 percent, Pakistan’s population increase is not expected to stabilize in the next three decades, even if Pakistan were to put in place a successful population control policy. For instance, MQM insists that Karachi has a higher population than the rest of Sindh. The PPP insists that Sindh’s population is larger than it is estimated to be in the latest census results. This insistence is not without logic, and is based on the historical experiences of the smaller provinces and minority ethnic communities within the federation. “While the current population census was conducted after a long delay, the country’s ruling elite has never used the census results beyond how it can or cannot help them in politicking, power grabs, undermining smaller provinces’ rights, and the redrawing of constituencies to ensure that the established political power sharing structure remains intact,” a political commentator in a foreign publication quipped. “Since Pakistan’s independence, the country’s smaller provinces have always protested against not receiving their due share in resources. They claim this has been due to the country’s politics being dominated by Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province. The ruling elite in Pakistan have not made any determined policy efforts to expand the country’s domestic economy by effectively increasing agricultural and industrial output. It’s one of the primary reasons that Pakistan remains unprepared for rising challenges that uncontrolled growth.”

Harvard economist David Bloom recently wrote a piece on Pakistan’s population trends in which he described “rapid population growth and the need to provide for the young as a “crushing burden” on the economy.” “

If, in 10 or 20 years, Pakistan still has a large number of unemployed or underemployed people, including tens of millions of young people, the country may face crises that dwarf those it has experienced to date,” he writes for a Pakistani publication.

Political opponents have turned into bloodthirsty enemies. In such a situation, policy making is far from a priority. Political leaders spend most of their time conspiring to defeat their opponents in the public space.

Sakib Sherani, a Pakistani banker and economist, recently wrote that “politicians are not thinking long-term. They are not thinking beyond an election cycle.” He notes the workforce has nearly doubled in the past two decades to 60 million, and the labor market needs to provide 3 million jobs a year for new entrants. “That’s just not happening.”

There are two major reasons why population trends or any other public policy issue for that matter, has not been included in political discourse or parliamentary debate as a worthy issue in its own right. Firstly, Pakistani political parties and political leaders are too busy fighting for their survival in a society which is deeply divided and political groups are at each other’s throats. Political opponents have turned into bloodthirsty enemies. In such a situation, policy making is far from a priority. Political leaders spend most of their time conspiring to defeat their opponents in the public space. This situation has not allowed the development of expertise among politicians that is required to guide and lead a policy making process in Islamabad’s officialdom that is dominated by stiff necked bureaucrats. The result of all this is that there is no discussion on population trends in society in the Parliament.

Obviously, bureaucrats can formulate policies but could not lead from the front, which is the forte of political leaders. Remember that international experts cite shyness and reluctance on the part of Pakistani political leaders as a major cause behind the failures of successive population planning programs in Pakistani society. This has allowed conservative forces in our society to take the lead and distort the message of population planning programs through their own counter narrative, which has proved very damaging for population planning.

Pakistan is going through a phase of demographic transition, experiencing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity of reaping the demographic dividend as the working-age population bulges and the dependency ratio declines.

Another major reason our political class doesn’t take population planning issues very seriously is the fact that these issues don’t get them votes in their constituencies. In the post-Zia period, social and political trends in our society have turned decidedly towards a conservative direction. One obvious reflection of this trend is the gradual phasing out of the party with left of center leanings. For example, the PPP has been restricted to Sindh province. It has been completely wiped out from Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Politics in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab are totally in the grip of conservative parties like PML-N and PTI. In local constituency politics, candidates and their leaders tend to concentrate on issues which can get them votes. Any issue that can challenge deep seated social and cultural attitudes and traits are largely ignored at the local level. Although the central political leaders of these parties still continue to pay lip services to these issues to portrait an image of moderation, this does not reflect in their policy or legislative preferences. Some analysts predict that in the coming elections, mainstream parties might ignore paying lip service to population planning issues on the pretext that after the passage of the 18th Amendment, this issue has been shifted to the provinces in the constitutional scheme of things. Population planning is now a provincial subject, which means national political leaders have an incentive to believe that it no longer requires any profound attention in the mainstream.