Sindh’s Thar desert has lost hundreds of lives and thousands of livelihoods in three consecutive drought years, and despite the government’s relief efforts, locals fear the worst is yet to come. Groundwater is sinking, thousands of cattle have either been sold or have died because of lack of fodder, and locals say if there is no rain this monsoon, there will be a famine like situation.

“In 2014, Thar received only 100mm of rain, which is less than normal,” says Tharparkar Deputy Commissioner Muhammad Asif Jameel. “This year so far, the region has only received 5mm, and in this condition, if there is no rain during the coming monsoon season, the situation will worsen.”

But the Sindh government is carrying out a massive relief operation, says Asif, who is also the district relief commissioner. “We will not allow the severity of the weather to take its toll.”

With 1.6 million people and 70 million livestock scattered on 22,000 square kilometers along the Indian border, eastern Sindh is part of the seventh biggest desert in the world, most of which lies in the Indian Rajasthan.

The drought began in 2013, first killing peafowl, then sheep and other animals, and finally people, many of who died because of poor nutrition. In February 2013, the Sindh government began to subsidize wheat in Thar, selling it at half the market price. After massive media coverage, the provincial government initiated a relief operation on March 9.

According to Relief Department data, 60 percent of the desert’s population was hit directly. The Sindh government chose 256,000 families (with an average of 5 people per family) who have been given wheat, ration bags consisting of sugar, flour, cooking oil and milk powder, and packets of dates, blankets in winter, and fodder for livestock, in several phases, says the relief commissioner. Of the 750 Reverse Osmosis plants it it had planned, the Sindh government has installed 375 so far. The rest, he says, will be functional by the next month.

But more than a thousand people have died since December 2013, despite the relief operations.

Senator Taj Haider, a PPP veteran and in charge of relief activities in Tharparkar district, says the dead include 159 adult men, 168 women and 726 children under five. Around 3,814 cattle have also been reported dead. “But in last 15 days, not a single death has been reported anywhere in the district,” he says. “We have initiated a massive relief operation, which consists of wheat distribution, vaccination of animals, installation of solar panels in the villages, RO plants and other projects to help the locals.”

Some locals say the measures are not enough. “We want a more permanent solution, such as the rehabilitation of the communities and development of the area, not just temporary relief work,” says Bharumal Amrani, a social worker in Tharparkar.

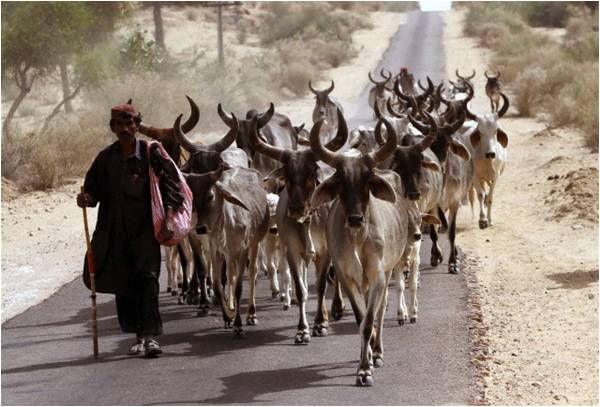

After a prolonged dry spell in Thar, a large number of people began moving north with their livestock, towards other districts of Sindh, in search of food and fodder. According to locals, when there is a serious drought, almost half the population migrates to the nearby districts, along with 40 percent of the livestock.

Officials say seasonal migration has a long history. “Whatever the severity of the drought is, not more than 10 percent of the total population migrates, and these are identified communities, such as Kolhi, Bheel and Menghwar, who have a long history of seasonal migrations,” says the Tharparkar deputy commissioner.

More than 60 percent of the total area of Sind – which consists of seven major climatic regions: Thar desert, Nara desert, Kachho, Achhro Thar or White Desert, Kohistan, Laar or southern Sindh, and Wicholo or middle Sindh – is part of Indus eco-region and are dependent on the water of River Indus. Apart from middle Sindh and parts of southern Sindh, these regions are arid or semi-arid because the Indus water does not reach them through a canal system. There areas are frequently hit by dry spells, but only the drought in Thar desert has been reported in the media.

Although such large areas of the province are arid, the Sindh government does not have an official drought policy with standardized relief and rehabilitation procedures. After the prolonged coverage of the Thar drought in the mainstream media, it constituted a committee to draft one. “We have put together a draft, but it has not become an official document yet,” says Sohail Solangi, a member of the committee and a noted journalist.

The committee has advised the government to build new “model” villages or towns in the Thar desert with basic facilities, so that people may migrate from remote villages to these new settlements. “Most plans in the past have been restricted to the agriculture sector,” he says. “We have also suggested that new policies should be made to develop the livestock sector, which is the main source of livelihood in the desert.” A portion of income from the local natural resources of Thar desert, such as coal, china clay, and granite, must be spent on the development of Thar, the committee has advised.

Amar Guriro is freelance journalist based in Karachi

Twitter: @AmarGuriro

“In 2014, Thar received only 100mm of rain, which is less than normal,” says Tharparkar Deputy Commissioner Muhammad Asif Jameel. “This year so far, the region has only received 5mm, and in this condition, if there is no rain during the coming monsoon season, the situation will worsen.”

But the Sindh government is carrying out a massive relief operation, says Asif, who is also the district relief commissioner. “We will not allow the severity of the weather to take its toll.”

With 1.6 million people and 70 million livestock scattered on 22,000 square kilometers along the Indian border, eastern Sindh is part of the seventh biggest desert in the world, most of which lies in the Indian Rajasthan.

The drought began in 2013, first killing peafowl, then sheep and other animals, and finally people, many of who died because of poor nutrition. In February 2013, the Sindh government began to subsidize wheat in Thar, selling it at half the market price. After massive media coverage, the provincial government initiated a relief operation on March 9.

According to Relief Department data, 60 percent of the desert’s population was hit directly. The Sindh government chose 256,000 families (with an average of 5 people per family) who have been given wheat, ration bags consisting of sugar, flour, cooking oil and milk powder, and packets of dates, blankets in winter, and fodder for livestock, in several phases, says the relief commissioner. Of the 750 Reverse Osmosis plants it it had planned, the Sindh government has installed 375 so far. The rest, he says, will be functional by the next month.

When there is a dry spell, half the population migrates northwards in search of food and fodder

But more than a thousand people have died since December 2013, despite the relief operations.

Senator Taj Haider, a PPP veteran and in charge of relief activities in Tharparkar district, says the dead include 159 adult men, 168 women and 726 children under five. Around 3,814 cattle have also been reported dead. “But in last 15 days, not a single death has been reported anywhere in the district,” he says. “We have initiated a massive relief operation, which consists of wheat distribution, vaccination of animals, installation of solar panels in the villages, RO plants and other projects to help the locals.”

Some locals say the measures are not enough. “We want a more permanent solution, such as the rehabilitation of the communities and development of the area, not just temporary relief work,” says Bharumal Amrani, a social worker in Tharparkar.

After a prolonged dry spell in Thar, a large number of people began moving north with their livestock, towards other districts of Sindh, in search of food and fodder. According to locals, when there is a serious drought, almost half the population migrates to the nearby districts, along with 40 percent of the livestock.

Officials say seasonal migration has a long history. “Whatever the severity of the drought is, not more than 10 percent of the total population migrates, and these are identified communities, such as Kolhi, Bheel and Menghwar, who have a long history of seasonal migrations,” says the Tharparkar deputy commissioner.

More than 60 percent of the total area of Sind – which consists of seven major climatic regions: Thar desert, Nara desert, Kachho, Achhro Thar or White Desert, Kohistan, Laar or southern Sindh, and Wicholo or middle Sindh – is part of Indus eco-region and are dependent on the water of River Indus. Apart from middle Sindh and parts of southern Sindh, these regions are arid or semi-arid because the Indus water does not reach them through a canal system. There areas are frequently hit by dry spells, but only the drought in Thar desert has been reported in the media.

Although such large areas of the province are arid, the Sindh government does not have an official drought policy with standardized relief and rehabilitation procedures. After the prolonged coverage of the Thar drought in the mainstream media, it constituted a committee to draft one. “We have put together a draft, but it has not become an official document yet,” says Sohail Solangi, a member of the committee and a noted journalist.

The committee has advised the government to build new “model” villages or towns in the Thar desert with basic facilities, so that people may migrate from remote villages to these new settlements. “Most plans in the past have been restricted to the agriculture sector,” he says. “We have also suggested that new policies should be made to develop the livestock sector, which is the main source of livelihood in the desert.” A portion of income from the local natural resources of Thar desert, such as coal, china clay, and granite, must be spent on the development of Thar, the committee has advised.

Amar Guriro is freelance journalist based in Karachi

Twitter: @AmarGuriro