Generally, political commentators attribute the emergence of authoritarian tendencies in governance to the personal style of political leaders. For instance, pro-PML-N commentators blame Imran Khan for witch hunts, curbs on media and attempts to stifle dissent - tendencies which became rampant during his time in office. Similarly, pro-Imran Khan commentators blame the Sharif brothers for the treatment meted out to PTI workers. Political commentators even get a little superstitious when they speak of the manhandling of political leaders they oppose at the hands of police, as retribution from God for what was done to their opponents during their time in power.

While it goes without saying that the mistreatment of Pakistani citizens and the denial of rights by the state’s machinery should come as a jolt to the moral conscience of all of society, it is ironic that what has been happening before our eyes for the past 15 years does not bother our conscience in the least. We are too busy in our petty political polemics, with the inevitable result that there is absolutely no voice in society that calls for resistance to the unfolding drama of the state machinery’s violation of political norms and values. No one seems to care about the damage being done to the political system in the long run. It is clear that we are living through a time of deep polarization, with political leaders selectively acting as cheerleaders of the state machinery while it goes about prosecuting their opponents. This means that oppression of political activists is becoming acceptable, as long as the activists belong to the opposing political party. The same oppression and curbing of the media becomes unacceptable if it is carried out against your own party’s people.

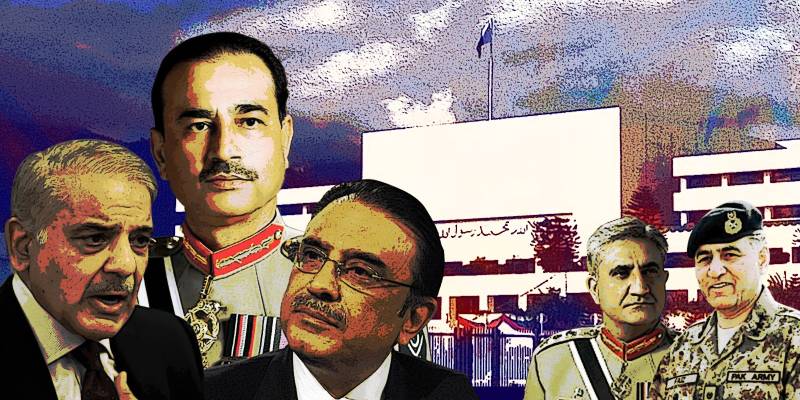

Ironically, no deep thought is given to how authoritarian tendencies started to creep into our system the moment parliamentary democracy was restored in the wake of General Musharraf’s resignation in 2008. We became a full-fledged parliamentary democracy in the wake of the 2008 parliamentary elections, after the PPP led Parliament repealed the contaminations introduced by the outgoing military government. The civil governments of Asif Ali Zardari inherited two insurgencies from the military government of Pervaiz Musharraf, one in the erstwhile tribal areas and another in Balochistan. Therefore, political freedoms in these two regions remained bleak and constrained, even when parliamentary democracy had been restored in the country. Enforced disappearances were rampant and remained so. The islands of freedom in the country - Punjab, Islamabad and Karachi were increasingly coming under the sway of authoritarian ways of handling political freedoms and civil liberties.

During the military rule of General Musharraf, Punjab saw a large number of cases of enforced disappearances. The military government, however, countered allegations by pointing out that they allowed media houses to open electronic channels, which was generally seen as a step towards unprecedented media freedom in the country. The military government then thought it appropriate to promote a Punjab-centric political culture, centered around Punjab, Islamabad and Karachi. If Balochistan and the erstwhile tribal areas ever figured in the news coverage of Pakistani media, it was in relation to the activities of the Pakistan military. What was unpalatable about situations in these regions was seldom shown on Pakistani screens.

By the end of the first decade of the restoration of parliamentary democracy, a rosy picture of Punjab, Islamabad and Karachi started to give way to anti-military establishment sentiments, where anti-military sloganeering became common in the political campaigns of Punjab-centric political parties. After the 2017 removal of a democratically elected Prime Minister from office as a result of a dubious trial, the situation truly entered the realm where no holds were barred, and the military establishment started to face scathing criticism from Punjabi political leaders.

The absence of an honest discussion on the structural reasons for the continued and increasing role of the military in managing political mechanics in our society is the elemental reason behind our blinkered view about the rise of authoritarian tendencies in our society. Political and media circles usually blame political leaders they oppose as the reasons for repressive and authoritarian tendencies. The military as an institution has always held a commanding position as far as decisions related to the use of force in society have been concerned.

The PPP government conferred the power to apply force in dealing with militant groups on the then COAS in 2009. This meant not only the power to exercise executive authority in the use of violence, but dominance of the intellectual tools to decide as to which forces are enemies of the state and which forces would be acceptable as legitimate players in the democratic process. It is no surprise that the year 2014, when the military started to make a decisive push against militants in the tribal areas, was also the time when part of the military establishment started a campaign to get rid of Nawaz Sharif. In the wake of the 2007 rise of TTP and the military's successive campaigns to flush them out from the border regions, the military started to dominate political and decision-making processes in the country. The military government might have gone in 2008, but the military continued to dominate decision-making, especially when it came to the use of the coercive machinery of the state. Initially, it was militant groups who were at the receiving end. Later, this coercive machinery was used against political forces opposed to the military.

The fact that Punjab-centric parties like PML-N and PTI have developed tendencies of their own to oppose the military’s dominance of the political system ultimately led to the deployment of repressive tactics to deal with issues related to political freedoms. These political forces were challenging the military on its home turf since the Pakistan military recruits mostly from Punjab. These political forces were targeting the military's vaunted reputation, a facet of its existence which its leadership values very highly.

In the wake of the 2017 removal of Nawaz Sharif from power, when PML-N workers and leaders were engaging in an anti-military establishment campaign, the Imran Khan government acted as a front for the military establishment and carried out a witch hunt against the former ruling party. Now there has been a role reversal, with the PML-N acting as the establishment’s front, and the PTI’s workers and leadership are at the receiving end. The PTI leadership, however, made the strategic mistake of using violence as a tool against symbols of the military establishment’s, in an apparent attempt to browbeat them. This mistake led to the opening of the floodgates of coercion and violence against PTI workers and the party cadre.

Two factors should be taken note of in the analysis of Pakistan’s path towards repressive and authoritarian tendencies. First, the military establishment has never withdrawn from the decision-making process in the wake of Musharraf’s removal from office. They continued to control the coercive instruments of the state as they did while the military was directly in power. Civil governments which came to power in the wake of Musharraf’s exit facilitated the military's control of the coercive machinery. They were inexperienced and afraid to deal with militant threats directly, and therefore delegated all powers to the military. This arrangement continues to this day. Second, the military, for the first time, faces a situation where Punjab-centric popular parties are raising their voices against the military's continued dominance of the political system. The military, which appears to be in love with its self-created image, cannot afford this kind of political activity on its home turf. The result lays before our eyes.

There is a serious potential for violence in this situation. Punjab’s middle classes have been facing economic hardships since this whole drama started to unfold. A rapidly devaluing currency, unemployment and price hikes are causing a shrinking of the Punjabi middle class, which has been deeply addicted to state subsidies since the time of the US backed military government of General Zia-ul-Haq. More than state oppression, the economic conditions of these middle-class multitudes will determine the fate of Pakistan’s political system. Oppression could prove to be a catalyst in the process of emerging street violence as a political norm.

While it goes without saying that the mistreatment of Pakistani citizens and the denial of rights by the state’s machinery should come as a jolt to the moral conscience of all of society, it is ironic that what has been happening before our eyes for the past 15 years does not bother our conscience in the least. We are too busy in our petty political polemics, with the inevitable result that there is absolutely no voice in society that calls for resistance to the unfolding drama of the state machinery’s violation of political norms and values. No one seems to care about the damage being done to the political system in the long run. It is clear that we are living through a time of deep polarization, with political leaders selectively acting as cheerleaders of the state machinery while it goes about prosecuting their opponents. This means that oppression of political activists is becoming acceptable, as long as the activists belong to the opposing political party. The same oppression and curbing of the media becomes unacceptable if it is carried out against your own party’s people.

Ironically, no deep thought is given to how authoritarian tendencies started to creep into our system the moment parliamentary democracy was restored in the wake of General Musharraf’s resignation in 2008. We became a full-fledged parliamentary democracy in the wake of the 2008 parliamentary elections, after the PPP led Parliament repealed the contaminations introduced by the outgoing military government. The civil governments of Asif Ali Zardari inherited two insurgencies from the military government of Pervaiz Musharraf, one in the erstwhile tribal areas and another in Balochistan. Therefore, political freedoms in these two regions remained bleak and constrained, even when parliamentary democracy had been restored in the country. Enforced disappearances were rampant and remained so. The islands of freedom in the country - Punjab, Islamabad and Karachi were increasingly coming under the sway of authoritarian ways of handling political freedoms and civil liberties.

During the military rule of General Musharraf, Punjab saw a large number of cases of enforced disappearances. The military government, however, countered allegations by pointing out that they allowed media houses to open electronic channels, which was generally seen as a step towards unprecedented media freedom in the country. The military government then thought it appropriate to promote a Punjab-centric political culture, centered around Punjab, Islamabad and Karachi. If Balochistan and the erstwhile tribal areas ever figured in the news coverage of Pakistani media, it was in relation to the activities of the Pakistan military. What was unpalatable about situations in these regions was seldom shown on Pakistani screens.

By the end of the first decade of the restoration of parliamentary democracy, a rosy picture of Punjab, Islamabad and Karachi started to give way to anti-military establishment sentiments, where anti-military sloganeering became common in the political campaigns of Punjab-centric political parties. After the 2017 removal of a democratically elected Prime Minister from office as a result of a dubious trial, the situation truly entered the realm where no holds were barred, and the military establishment started to face scathing criticism from Punjabi political leaders.

The absence of an honest discussion on the structural reasons for the continued and increasing role of the military in managing political mechanics in our society is the elemental reason behind our blinkered view about the rise of authoritarian tendencies in our society. Political and media circles usually blame political leaders they oppose as the reasons for repressive and authoritarian tendencies. The military as an institution has always held a commanding position as far as decisions related to the use of force in society have been concerned.

The PPP government conferred the power to apply force in dealing with militant groups on the then COAS in 2009. This meant not only the power to exercise executive authority in the use of violence, but dominance of the intellectual tools to decide as to which forces are enemies of the state and which forces would be acceptable as legitimate players in the democratic process. It is no surprise that the year 2014, when the military started to make a decisive push against militants in the tribal areas, was also the time when part of the military establishment started a campaign to get rid of Nawaz Sharif. In the wake of the 2007 rise of TTP and the military's successive campaigns to flush them out from the border regions, the military started to dominate political and decision-making processes in the country. The military government might have gone in 2008, but the military continued to dominate decision-making, especially when it came to the use of the coercive machinery of the state. Initially, it was militant groups who were at the receiving end. Later, this coercive machinery was used against political forces opposed to the military.

The fact that Punjab-centric parties like PML-N and PTI have developed tendencies of their own to oppose the military’s dominance of the political system ultimately led to the deployment of repressive tactics to deal with issues related to political freedoms. These political forces were challenging the military on its home turf since the Pakistan military recruits mostly from Punjab. These political forces were targeting the military's vaunted reputation, a facet of its existence which its leadership values very highly.

In the wake of the 2017 removal of Nawaz Sharif from power, when PML-N workers and leaders were engaging in an anti-military establishment campaign, the Imran Khan government acted as a front for the military establishment and carried out a witch hunt against the former ruling party. Now there has been a role reversal, with the PML-N acting as the establishment’s front, and the PTI’s workers and leadership are at the receiving end. The PTI leadership, however, made the strategic mistake of using violence as a tool against symbols of the military establishment’s, in an apparent attempt to browbeat them. This mistake led to the opening of the floodgates of coercion and violence against PTI workers and the party cadre.

Two factors should be taken note of in the analysis of Pakistan’s path towards repressive and authoritarian tendencies. First, the military establishment has never withdrawn from the decision-making process in the wake of Musharraf’s removal from office. They continued to control the coercive instruments of the state as they did while the military was directly in power. Civil governments which came to power in the wake of Musharraf’s exit facilitated the military's control of the coercive machinery. They were inexperienced and afraid to deal with militant threats directly, and therefore delegated all powers to the military. This arrangement continues to this day. Second, the military, for the first time, faces a situation where Punjab-centric popular parties are raising their voices against the military's continued dominance of the political system. The military, which appears to be in love with its self-created image, cannot afford this kind of political activity on its home turf. The result lays before our eyes.

There is a serious potential for violence in this situation. Punjab’s middle classes have been facing economic hardships since this whole drama started to unfold. A rapidly devaluing currency, unemployment and price hikes are causing a shrinking of the Punjabi middle class, which has been deeply addicted to state subsidies since the time of the US backed military government of General Zia-ul-Haq. More than state oppression, the economic conditions of these middle-class multitudes will determine the fate of Pakistan’s political system. Oppression could prove to be a catalyst in the process of emerging street violence as a political norm.