Millions of solar panels are set to be mounted upon swathes of soil in Block VI of Tharparkar district’s coalfields in Pakistan – news that is making waves locally. Located 380 kilometres east of Karachi in Sindh province, these coalfields are divided into 14 blocks, but so far work has only begun in blocks I and II.

“It will be the largest [single solar plant in Pakistan] by a single entity,” says Naheed Memon, chief executive officer of the UK-based Oracle Power, the mining company behind this much-touted one gigawatt (GW) project.

If completed, the project could significantly help Pakistan to achieve its goal of deriving 60% of its energy from renewable sources by 2030. However, this particular solar project is being built in the shadow of ongoing coal projects in the Thar desert. In fact, Oracle Power is developing both solar and coal in the province.

Thar’s coalfields cover an area of 9,100 square kilometres and contain over 175 billion tonnes of lignite – a poor-quality and commonly more polluting type of coal. These lignite reserves are among the largest in the world.

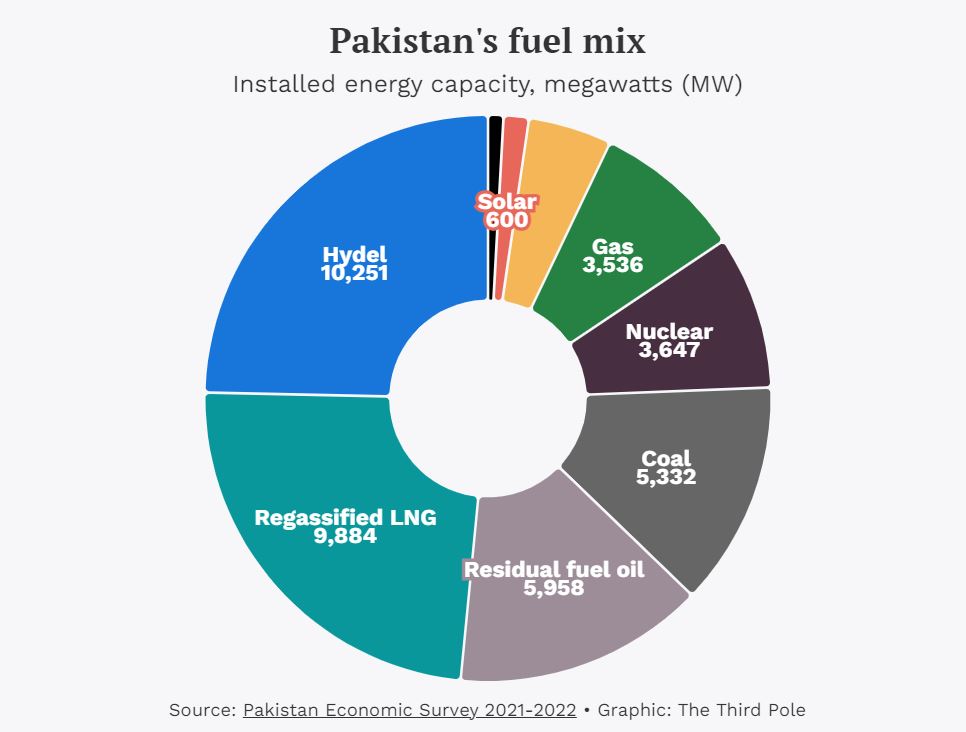

Source: Pakistan Economic Survey 2021-2022 • Graphic: The Third Pole

‘Greening’ the coalfields

The solar project’s pre-feasibility study was completed by PowerChina, a Fortune 500-listed construction group. According to an agreement signed between Oracle and PowerChina in April 2023, the companies will work together in conducting the project’s necessary surveys; it also allows PowerChina to help arrange project finance. Elsewhere, the agreement includes references to a green hydrogen production facility being jointly pursued, 250 km away from Block VI.

The agreement details Oracle’s initial technical plan for the 1GW solar project, which proposes that it be developed on the “peripheral land of the mining area, occupying less than 25 percent of the Thar Block VI, and generating power from the Thar desert from a completely renewable source”. It also says the solar plant will be “deployed outside the potential built up and impact area of any coal-related project in the future”.

“Solar in Thar is an important initiative,” says Cheng Qiang, a spokesperson for PowerChina. The company has completed one solar and 23 wind projects in Pakistan.

“We want to generate renewable power in the desert for other mining operations as well as the railway line that is in the pipeline; our solar project will offset carbon emissions from the coal that is being mined and used to fire the two power plants [in Block 2],” Cheng added.

We asked Azhar Lashari, research and advocacy coordinator at the Policy Research Institute for Equitable Development, to put PowerChina’s carbon offsetting claims into perspective: “The narrative of ‘offsetting carbon emissions’ is controversial. It is nothing but continuing ‘business as usual’ and ‘greenwashing’ on the part of banks, companies and corporations like Oracle and PowerChina. How can a solar project neutralise the carbon emissions?”

With a 30-year mining lease of Block VI, Oracle Power has wanted to set up a 1,320 MW coal plant since 2016, when this was included in a list of energy projects under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). But this particular project has so far stalled due to financial hurdles.

We are not abandoning hydrocarbons and our coal project is under development

Oracle’s Memon is adamant that the company is not turning its back on coal: “We are not abandoning hydrocarbons and our coal project is under development. We will complete it and are working with private investors.” Memon does concede, however, that financing continues to be a stumbling block.

The CEO also says that “dirty fuel cannot be eliminated completely” and that it “will be a gradual transition over the next few decades”. In the interim, she says, Pakistan is in “critical need of cheap, local, indigenous fuel-based power as base load, be it coal, oil or gas”.

Doing solar right in Pakistan’s Thar

“[Thar solar] will be an excellent opportunity for Oracle to diversify from its fossil-based portfolio,” says Haneea Isaad, an energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. She also says that solar will be valued by local communities and could increase the productive use of energy in the region.

But the 1GW solar project also brings with it the risk of negatively impacting local communities. The project will use a large area of land (around a quarter of Block VI’s leased 66.1 sq km) to put up around 1.52 million solar photo-voltaic panels. Despite Oracle’s agreement with PowerChina, stating that the project will be developed on “unutilized land”, Memon concedes that the solar project may mean relocating some villages. “Resettlement will be done in line with the government’s directions,” she says, with provision of “all the necessities of life, like drinking water, shelter for animals and fodder”. In some cases, Memon says low-cost housing will be considered.

Memon claims she does not know which villages could be relocated; Lashari finds this hard to believe: “Memon must know the number of villages and the population that will be displaced, because displacement and relocation is inevitable since this involves massive land acquisition.”

When [the communities’] land is taken away, some lose their only means of livelihood and some the only occupation they know

Azhar Lashari, Policy Research Institute for Equitable Development

Lashari adds that displacement involves both physical dislocation and livelihood disruptions: “When [the communities’] land is taken away, some lose their only means of livelihood and some the only occupation they know. They also lose the nearby grazing ground for their livestock. Often the pittance some get in the form of compensation is unwisely invested and so they are poorer off than they were before.”

According to Akram Ali Lanjo, a shopkeeper in the Thar village of Kharo Jani, the local community’s most pressing need is drinking water for households and livestock. These desert families rely on groundwater, which has turned ‘very salty’. Lanjo told us: “If anyone can turn our salty water to sweet, our woes will be addressed to a large degree.”

Lanjo also says that, while the villagers have nothing against the development itself, they would never part with their ancestral lands: “We can lease it out, but never sell it. And we do not want to be displaced.”

Lanjo cites the example of the Sehri Dars village, which was “decimated”. Its residents were relocated to a new village with the same name, built by the Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company. Both Lanjo and Lashari claim that the displaced villagers are unhappy in their new location.

As for concerns around water scarcity, Memon had this to say of the project: “There will be zero consumption of water for the cleaning of solar panels, as we will bring in state-of-the-art automatic cleaning robotic technology, which will keep the solar panels clean and in optimum form for maximum power generation.”

Sindh government ambitions

Oracle is currently looking to bring in international financiers to invest in its Thar solar project, as the Sindh government does not have a direct incentive for such projects. Nonetheless, it is keen to get the project off the ground.

Imtiaz Ali Shah, director of renewable energy at the Sindh government’s energy department told The Third Pole, “We will facilitate and support this attractive green energy project in every way, but the company needs to come up with a solid purchase agreement, their guarantors, a final study and a firm strategy.”

However, Shah acknowledges that more needs to be done for those areas that are not on the national grid, or those facing power outages: “Tharparkar district is one of the remotest and least-developed. If all the power produced by Oracle’s solar project is used there, I would consider it a big success as it will better the lives of the locals.”

People from different companies come, do surveys, make tall promises, and never return

Akram Ali Lanjo, shopkeeper in the Thar village of Kharo Jani

Shah also hopes that the project will provide livelihood for the locals. Parasram Archand, a 22-year-old teacher in a private primary school in Kharo Jan, doubts this claim, because most of the local villagers are uneducated. “But they can do labour [at the site],” counters Lanjo, who himself remained in formal education until he was 13.

“We would ensure most labour is local,” adds Memon, “especially during the construction when the company would need up to 2,500 people. [This] will be reduced along the way to 700 to 1,000 during operation and maintenance.”

Lanjo admits to feeling hopeful when a team from the city first visited the village some months ago and talked of the potential for a solar plant. On the other hand, he remains sceptical: “People from different companies come, do surveys, make tall promises, and never return.”

Disclaimer: This piece was originally published here.