During a session on a book of mine at the 2022 Lahore Literature Festival, a young man in the audience asked as to why so many ‘liberal-looking’ or ‘liberal-sounding’ folk supported Imran Khan. He asked this, despite the fact that by 2022, Khan had mutated into becoming a contemporary right-wing populist who seemed to be more fluent in airing reactionary views on various social issues than he was in the art of governance. The more he found himself cornered by the demands of running a complex country, and the more he blundered in matters of governance, the more rigid and hidebound his rhetoric became.

This former star cricketer, socialite, ‘playboy’ and darling of the tabloid press took a rightward turn after he retired from cricket in 1992 and ‘rediscovered’ his faith. He also began to reassess the manner in which he understood Pakistani society. During this reassessment, he concluded that Pakistani society was organically conservative, but was being adulterated by alien Western ideas and trends and exploited by a ‘corrupt political mafia’ and by ‘US/European neo-imperialism.’

Unlike most Pakistani sportsmen who often come from lower-middle-class and working-class backgrounds, Khan came from an upper-middle-class family. And here lies the answer to the aforementioned question. Khan’s transformation was very much in line with the manner in which the Pakistani middle-income segments have been evolving from the 1980s onwards. I was too young to fully remember the movement against the ZA Bhutto regime in 1977. However, as I entered my teens in 1980, I began to notice that most lifestyle liberals were overtly supporting the reactionary military regime led by General Zia-ul-Haq — the man who had toppled the Bhutto government and then sent the former prime minister to the gallows.

This had confused me. Of course, being very young at the time, I had a rather binary view of the two regimes: Bhutto’s regime was liberal, and the one that overthrew it was conservative. And in Pakistan, conservatism is often paired with Islamism. As I grew a bit older and entered college in 1985, I began to understand that what differentiated Bhutto from Zia was a lot more complex and had a lot to do with economics.

In his book Middle Class, Media and Modi the Indian author and journalist Nagesh Prabhu writes that multiple governments headed by India’s founding party – the Congress – had succeeded in lifting the economic status of many Indians. But most among those who benefited from these policies largely turned right, instead of becoming a constituency of the Congress. This is not an uncommon occurrence. For example, various political scientists and economists who investigated the collapse of Soviet communism in 1991 were of the view that the socialist economy in the former Soviet Union and in its allied countries in Eastern Europe, succeeded in greatly improving the living standards of their citizens. Yet, the ruling communist parties there struggled to gain any measure of genuine support from the beneficiaries.

In a 2002 essay, the Russian cultural critic Maya Turovskaya wrote that many people in the former Soviet Union (and in communist ‘East European’ countries) had risen to become ‘middle-class,’ even though the economy was entirely managed by the state, and everyone was supposed to be ‘equal.’

It was always impossible for the Soviet state, though, to suppress the traction of luxury goods that were celebrated and flaunted in the non-communist US and ‘West Europe’. To the ‘middle-classes’ in communist countries, these luxury items and cultural products began to be viewed as the result and manifestation of ‘Western democracy.’

According to the Russian author and economist Grigorii Khanin, the Soviet economy “genuinely flourished” in the 1950s and 1960s. The British economist Philip Hanson agreed with Khanin in his book The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Economy. He wrote that, till the late 1960s, the Soviet economy “tended to grow faster than that of the United States.” The same was the case in the East European countries that were following the ‘Soviet model.’ Yet, in 1956 and 1968 respectively, there were serious uprisings in Hungry and the erstwhile Czechoslovakia against the ruling communist parties. Much of the opposition in this regard was made up of ‘lapsed communists,’ and those who were at the core of what Turovskaya later described as the middle-class in communist countries. They also received support from ‘Church groups’ that had otherwise been strictly regulated by the state.

In China, after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, and the demise of his iconoclastic variant of Marxism-Leninism, the ruling Chinese Communist Party introduced a number of unprecedented economic reforms which saw the gradual opening up of the Chinese economy, and the subsequent emergence of a Chinese middle-class. However, by 1989, young people who had benefited from the new economic policies, took to the streets in a bid to remove the government. They did not become supporters of the regime and the party that had elevated their economic status. Instead, they turned against these, and demanded democracy, freedom of speech and the freedom of practicing religion. They were ruthlessly crushed.

The phenomenon of many people from the Pakistani middle-classes turning against the military establishment (ME) after Khan’s fall in April 2022 is also a case in point. The middle-classes are an important segment which make vital contributions to the economy. They are also a skilled and educated white-collar workforce. But as they succeed in gaining economic influence, they then want to bolster this influence with political influence. Political influence and power are largely in the hands of ruling elites that are a class apart. In former communist countries, these elites were often found sitting at the top in the ruling communist parties. In established democracies, the ruling elites are embedded in the ‘pro-status quo’ institutions.

In most countries, the middle-classes expanded during the rule of established political parties. Many of these parties were on the left or leaning left. They were caught between serving their core constituencies (ie. classes below-the-middle or BTM) and an expanding middle-class. As the middle-classes gradually swelled, they increasingly became suspicious of the rhetoric, policies and programmes of the parties that still largely aimed to draw electoral traction from the BTM classes.

There is great drama in the process of leaders being lifted and put on a pedestal by admiring crowds and then pulled down and shredded by the same people. Such leaders believe they will be loved and adored forever. They were loved for what they had promised. But the promises are always too tall

The middle-classes felt that they were being ignored and that the fruits of their ‘honest hard work’ and taxes were being spent on BTM classes. As a result, from the 1990s onwards, left-leaning parities in Europe and the US refigured their orientation by pulling back various welfare programmes. This eventually saw their working-class constituencies become increasingly attracted by the rhetoric of right-wing populists. The populists claimed that the established parties were entirely elitist and therefore unwilling to address the issues faced by the working-classes. And so, the ‘common folk’ (mostly white) segments of the polity rallied behind the populists. Donald Trump is an excellent example.

In developing countries such as India, the economic liberalisation introduced by the left-leaning Congress in the 1980s initiated the rapid expansion of the middle-classes. But the Congress failed to find any traction from among these classes because the party was still claiming to be working towards ‘removing poverty.’ According to the French political scientist Christophe Jaffrelot, the Indian middle-classes became suspicious of the ‘Nehruvian socialism’ of Congress. They saw themselves as the main engines of the post-1980s economic growth in India. The issues faced by the BTM classes are of no concern to them. The Indian middle-classes insist that they deserve a larger share of power to determine the country’s economy, politics and culture.

From the late 1970s, religion has played a major role in the articulation of middle-class rebellions, especially in Asia. One of the main centres of the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran was the bazaar dominated by the lower-middle and the old middle-classes. They were aided by the new middle-classes, even though these had been one of the direct beneficiaries of the Shah’s ‘modernisation’ policies. The 1977 movement against the Bhutto regime was largely led by the country’s middle-and-lower-middle-class segments. Their grudge with the regime was economic in nature because they felt threatened by Bhutto’s policies of nationalisation. These segments were supported by the industrial class which, till the 1960s, was supporting the ‘modernist’ dictatorship of Ayub Khan. It pragmatically embraced Zia’s ‘Islamisation’ project which he linked to his policies of economic liberalisation.

By the late 1980s, this nature of pragmatism had become an established behaviour when, increasingly, the ‘sacred’ became public and the secular was pushed into the private sphere. The middle-classes were okay with this. The link between religion and modern material benefits was further strengthened by various Islamic evangelical outfits that began to emerge. These were funded by traders, industrialists, shopkeepers, etc. In her book The God Market, the Indian historian Meera Nanda writes that in South Asia, exhibitions of excessive religiosity are more common in upper-and-middle-class segments. This challenges the long-held modernist theory which posits that education and economic prosperity mitigates religiosity and relegates it to the private sphere. There is now increasing evidence (at least in South Asia) suggesting that lower-middle, middle, and upper-middle-class groups are more active in exhibiting religiosity than the classes below.

According to Nanda, the 1980s’ economic liberalisation in countries whose economies had previously been heavily regulated and centralised, produced a curious phenomenon: as economic regulations by the state and governments loosened, deregulated economic activity merged with religious activities. This may be because economic regulation, and even so-called ‘mixed economies,’ were perceived as being ‘socialist.’ This perception was the strongest in high-and-middle-income groups in India and Pakistan.

Consequently, many beneficiaries of a deregulated economy became overtly exhibitionistic about their faith. Even lifestyle liberals among them did not hide their sympathy for political conservatism. In India, the right-wing BJP got an overwhelming mandate in the elections from the country’s middle-income groups. The party also has burgeoning relations with some of India’s wealthiest entrepreneurs. The same was the case with Imran Khan’s PTI in Pakistan. PTI signalled neoliberal economic policies but peddled them as corruption-free-economics that would erase the ‘elites.’ The party also usurped the rhetoric of the religious parties. The PTI became the embodiment of the economic marriage between the higher/middle-income groups and religiosity.

The upper-and-middle-classes were expected to adopt and proliferate progressive currents in politics and the polity. But these classes, in South Asia, have become uncanny patrons of Political Islam and of Hindu nationalism. A desperate and failing Imran Khan began manifesting this with a lot more urgency. And his middle-class constituents responded to this with a muddled point of view: from throwing around the worn-out anti-corruption rhetoric, to the party’s social media accounts sharing fake quotes of philosophers to wrap Khan’s reactionary tirades with the ‘New Age’ prattle associated with the pop-Sufism that lifestyle liberals were/are so fond of.

The Awestruck Effect

There is great drama in the process of leaders being lifted and put on a pedestal by admiring crowds and then pulled down and shredded by the same people. Such leaders believe they will be loved and adored forever. They were loved for what they had promised. But the promises are always too tall. Once it becomes apparent that the promises were mere rhetoric, former admirers react in three ways:

(1) they feel their intelligence was insulted and their emotions exploited. They want to tear into the leader in any way possible. Picture the fate of the Italian fascist Mussolini.

(2) They feel ashamed that they so unabashedly fell head-over-heels over a charlatan. Not only do they feel disappointed by the leader, but in themselves as well. They are not very vocal about this realisation, though. They just become quiet.

And (3), they furiously repress realisations 1 and 2, as if these were not emerging from within but being fed from outside. They want to retain the feelings of excitement and fondness that the rhetoric had originally generated in them. This may cut them off from reality, in ways the elation and exhilaration of being put on a pedestal had separated their beloved leader from reality.

One saw all three reactions sweeping across Imran Khan’s supporters, as it became more than evident that he will not complete his full term. Khan, too, began to seethe with anger, disappointment, confusion and a sense of betrayal. His regime had been a disaster on numerous fronts. And the charisma that had worked so well for him, seemed to be eroding.

In India, the economic liberalisation introduced by the left-leaning Congress initiated the rapid expansion of the middle-classes. But the Congress failed to find any traction from among these classes

Charisma is a curious thing. In the book Denying to the Grave, Sara and Jack Gorman write that one of the ways ‘charismatic’ leaders justify the nature of power they wield is by constantly claiming that there is no other alternative. Khan kept repeating this. Such leaders aim to create a perception of a crisis when there is none. They then repeatedly claim that they alone are the best choice to resolve the crisis. Khan is still quite capable of seeding such a perception and then positioning himself as the only man willing and skilled enough to resolve ‘the crisis.’

What is a charismatic leader? The idea of a charismatic leader stems from the works of the German sociologist Max Weber (d 1920). He coined the phrase ‘charismatic authority,’ or authority that flows from the charisma of a leader. According to Weber, charisma in a person is because of a quality or personality trait by virtue of which he is set apart from ordinary men. Weber explained charismatic authority in contrast to ‘traditional authority’ and ‘rational authority.’ Traditional authority flows from established customs, and rational authority through institutions of the state.

Charismatic authority comes from a leader created by the ‘cult of personality.’ Having charisma and/or the ability to instantly charm and persuade a large group of people is not a negative trait. But when charisma is used politically, the outcome is often dark. Those who are not smitten by charismatic leaders often dismiss them for being eccentric and even comical. But charismatic leaders are well aware of their ability to effectively manipulate their audience. People hang on to their every word, no matter how exaggerated, inaccurate, or, for that matter, silly. Think Trump.

Charismatic leaders are especially attractive during times of crises. But it is also a fact that the crises are not always as grave as portrayed by the leader. Such leaders paint a crisis that they claim only they can resolve. Also, they can create a perception of a crisis when there is none or change the nature of a crisis according to their political needs.

During the campaigning for the 2013 elections in Pakistan, when terrorism had hit a terrifying peak in the country, Khan chose to put ‘corruption’ at the top of Pakistan’s list of crises. He hardly ever mentioned terrorism in his speeches. He continued to roll with his anti-corruption mantra even when he lost the 2013 elections to the PML-N. He then explained the PML-N government — and not the violent extremists that had slaughtered thousands of people — as ‘a grave danger’ to the country (because of its ‘corruption’).

This, despite the fact that the economy had begun to actually show signs of some recovery. But if this really was the case, then why were so many from the middle-classes rallying around Khan? A German researcher Jochen Menges led a study to explore the impact of charismatic leaders on their followers. His findings led to what he called the ‘awestruck effect.’ According to Menges, a lot of people suspend their emotions while listening to charismatic leaders. This hampers their ability of critical thinking. Menges adds that "charisma as a dominant behaviour is successful only when it is matched by submissive behaviour on the part of a leader’s followers." The German psychologist Sigmund Freud (d.1939) wrote about ‘transference,’ in which a person or group forms an idealised image of a father or mother figure and then projects this image onto a leader. The leader tries to enhance this idealised image of himself. In politics, this is often done by the creation of the cult of personality.

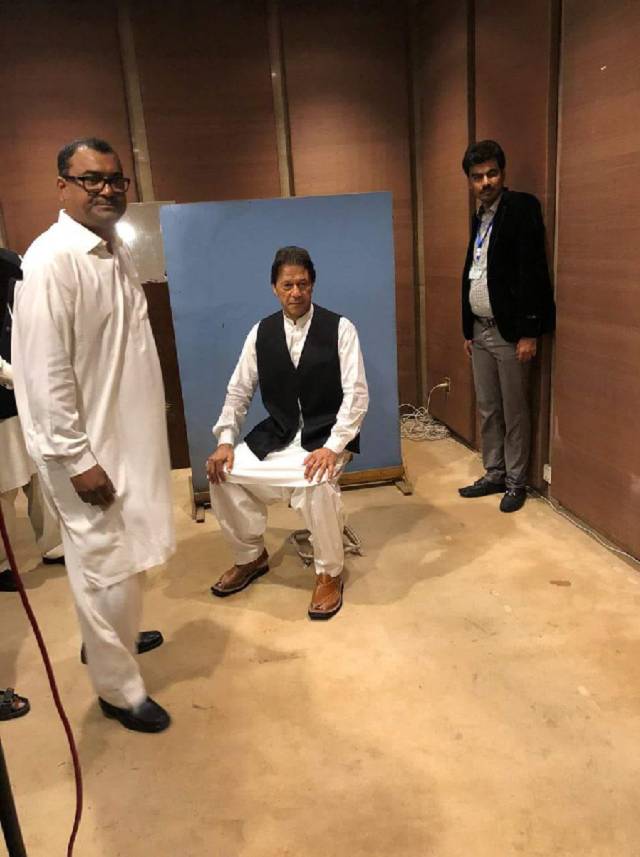

For example, photographs of Khan performing prayers, or working out, or speaking to a group of youth, etc., were floated across social media sites to substantiate the idealised image of him being a morally correct and physically fit father figure, who could do no wrong. But the fact is: all that he did do was mostly faulty. The stories behind the faults begin to ‘leak’ in the public when a charismatic leader’s downward trajectory commences. The harder he tries to arrest the slide, the harder he falls. And the fall can have a rather traumatic impact on many of his supporters. They might feel lost. They had identified Khan as a father figure. Or maybe even a messianic figure that they could actually see in ‘real’ life. To many, he was still the dashing man who won the 1992 Cricket World Cup.

Between 2008 and 2015, Pakistan was facing an unprecedented onslaught from militant Islamist groups. Suicide bombers were exploding themselves in markets and even in mosques, almost on a daily basis. Khan recast the fear of extremist violence as something to do with corruption. So instead of extremism, corruption became the fear, at least to his supporters. Khan then offered his growing number of followers punching bags in the shape of Nawaz Sharif and Asif Ali Zardari.

Losing it

There is a decreasing likelihood of Khan ever being able to bounce back and return to power. At least not in the next two years or even more. He isn’t getting any younger. The way he responded to his ouster, only strengthened the perception that he is unfit to lead a complex country such as Pakistan. He doesn’t have many friends left in the military, even though one can’t say the same about his ‘friends’ in the judiciary and in the media. Some are still there and he has made some new friends. But their influence is weakening. The judiciary that was heavily tilted towards him has entered into a battle of its own. Various judges are pushing back the military and the current coalition government from further denting Khan’s chances. But there is nothing new he has to offer. Therefore, for months after his dismissal, all he tried to do was whip up the emotions of his supporters, portraying himself as a victim of diabolical conspiracies.

The military establishment, which is still a powerful player and has a say in civilian political equations, has already confessed that the ‘hybrid regime’ project headed by Khan — formulated by the military in partnership with some senior judges and TV journalists — was a disaster. It brought the country’s economics, foreign policy and politics at a dangerous impasse. There is no foreseeable possibility that the military will be willing to tolerate Khan’s return to power. Especially after the 9th and 10th May 2023 fiasco in which PTI members and supporters set out to attack military properties, thinking their actions would split the military and bring ‘pro-Khan’ generals to power.

At the moment, the military establishment is not willing to even secretly talk to him as he languishes in jail on various charges of corruption and even ‘treason.’ He’s gone back and forth in exhibiting a willingness to talk and then announce he doesn’t want to talk. PTI insiders, however, confirm that he is desperate to start a dialogue with the ME (but not with the government).

In 2018, an election was allegedly rigged because PTI’s middle-class vote-bank wasn’t large enough to produce a convincing win. Khan became PM and headed a coalition government clubbed together with the help of the military. ME’s experiment of shaping and installing a hybrid regime was a success. But soon, the experiment started to unravel, putting the military on the spot. Once Khan began to lose the support of his erstwhile makers, his regime crumbled. Could the military not see that the experiment was bound to fail? Especially with a volatile character such as Imran Khan being at the centre of the experiment?

After repeating over and over again that his regime was ousted by the US, Khan then suddenly tried to sound pro-US by ‘clarifying’ that it wasn’t the US, but his former mentor and facilitator General Bajwa who ousted him. Of course, he said this three months after Bajwa retired as Army Chief. But it was too late. Khan had lost all support in the establishment. 2023’s 9th and 10th May riots were an outcome of this daunting realisation in the party.

What about his core constituency, the urban middle-classes? Some of them hope that Khan will take the lead after being behind (like his cricket team did in 1992) and win the top slot again. Some have already begun to dream of the emergence of yet another ‘strongman.’ Some have returned to being apolitical again. The fact is that, the attempt by the middle-classes to grab political power was sabotaged by their own messiah. Now the question is, how long before this class once again falls for a glorious fantasy fed to them by cynical kingmakers? Or will it learn anything from a disaster that they were a part of? Will they ever overcome the angst of facing a reality that they detest: the reality of Pakistan as it is — complex, chaotic, and diverse? Or will this class continue to reside in a conceptual reality in which it alone calls the shots? This class has demonstrated social and economic dynamism. But its political thinking and desires have remained muddled. Even delusional.