The debate surrounding the repatriation of Afghan refugees from Pakistan has attracted a vigorous discussion concerning the moral and humanitarian aspects of this decision. The legal aspect is debatable as well, with the matter already in the Supreme Court of Pakistan. However, it's crucial to assess the pragmatism of this decision – will it align with Pakistan's foreign policy interests, and what impact might it have on domestic conditions?

It is widely believed that Pakistan's decision to expel Afghan refugees was taken to exert pressure on the Tehreek-e-Taliban Afghanistan (TTA) in order to encourage their cooperation in addressing the issues related to the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). The TTA, following its takeover of Kabul, has shown reluctance in taking action against the TTP leadership, which enjoys a safe haven and freedom in Afghanistan. The TTP has noticeably intensified its violent activities in Pakistan, both in terms of frequency and severity.

Although the government initially announced November 1, 2023, as the deadline for undocumented or illegal foreigners to leave, denying that it was Afghan-specific, it is evident that the focus is primarily on searching for Afghan refugees. There have been reports of harassment and arrest of numerous Afghan refugees, including women and children, and the demolition of their properties in various locations. The state appears to make little distinction between the registered and unregistered refugees, as many with valid documents are also being subjected to forced eviction.

This may be attributed to the general behaviour of the police, which often falls short of expectations even when dealing with Pakistani citizens. However, they appear to be more stringent when dealing with Afghan refugees. There have also been reports of documented refugees having their Proof of Registration (POR) cards and passports torn or confiscated.

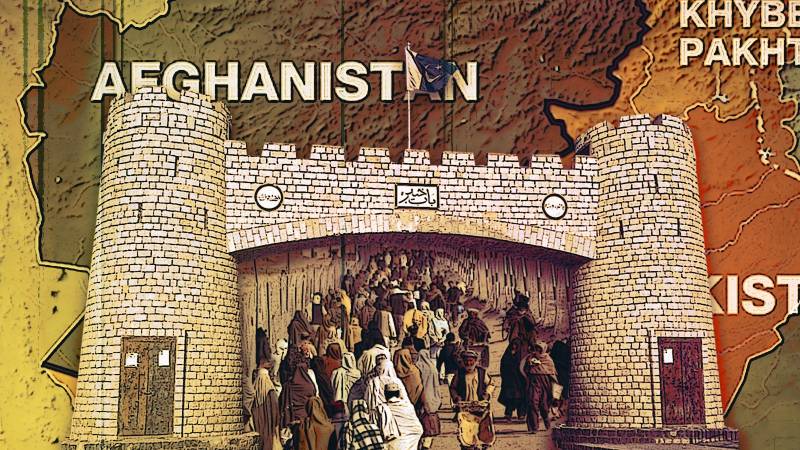

Setting aside the questions of legality, morality, or politics surrounding the expulsion, the ill-planned, rushed, and mismanaged implementation of deporting the estimated 1.7 million Afghans, claimed to be undocumented is giving rise to additional problems and resentment. Thousands find themselves waiting in the open air at the border crossing for days, trying to complete the required formalities before being expelled. Moreover, returning Afghans are not allowed to take their livestock, essential items, or more than Rs50,000 per family with them. There are reports of rampant bribery and looting exacerbating the situation.

It seems unlikely that the TTA will take action against the TTP, if for no other reason than the fear of losing support from most of its mid and low-level ranks, which has developed camaraderie with the TTP fighters.

The state's argument that the expulsion will help curb the rising spectre of terrorism is unfounded. Even if a few Afghans have been involved in certain terrorist activities, none of them arrived here as refugees, registered or unregistered. The overwhelming majority of those involved in such activities are Pakistani nationals. If the aim is to pressure the TTA government into cooperating on TTP matters, the expected results are unlikely to outweigh the costs associated with the policy and method of expulsion.

TTP fighters had fought alongside the TTA against foreign troops and the Afghan army. Pakistan was aware of this but chose to turn a blind eye, instead accusing the Afghan government and even India of protecting the TTP. Further, Pakistan welcomed the TTA takeover of Afghanistan, even releasing a significant number of TTP members from jails.

Therefore, it appears improbable that the TTA will take action against its former allies, if for no other reason than the fear of losing support from most of its mid and low-level ranks, which had developed camaraderie with the TTP fighters.

More importantly, a majority of Afghans who sought refuge in Pakistan, especially in recent years, are mostly undocumented and left Afghanistan due to the fear of the Taliban. Many of them are neither supporters nor opponents of the TTP.

Thus, the TTA is unlikely to be significantly affected by the hardships faced by these people.

It's an improbable scenario that these actions will create economic and administrative problems for the TTA, and make them yield to Pakistani pressures. The TTA appears to be less concerned about the economic well-being of the people, as is demonstrated by their uncompromising response to economic sanctions.

On the contrary, these actions may breed resentment and strengthen anti-Pakistan sentiments among Afghans. This may also push the TTA towards supporting the TTP, rather than ignoring them or allowing them to exist without interference. They may see support for the TTP as a counter-pressure tactic. This could result in further damage to Pakistan-Afghanistan relations.

The ill feelings among returning or potential non-returning Afghans will deepen, making it almost insurmountable to address the longstanding mistrust among Afghans. Whether this mistrust is justified or not is beside the point.

Also, the economic burden argument does not withstand scrutiny. Most Afghans, especially the undocumented ones, are not a strain on Pakistan's economy. In fact, many have injected capital into Pakistan's economy. The policy of not allowing those who return to take more than Rs50,000 will not benefit Pakistan significantly but will further victimise ordinary Afghans. The wealthier individuals, who are mostly documented and have substantial investments in Pakistan, may also be apprehensive and considering relocating their investments to safer places, and some may have already done so and will likely reconsider Pakistan as a secure place for investment.

The policy of repatriation of Afghan refugees and its implementation might not assist Pakistan diplomatically. Pakistan might risk losing whatever little goodwill it had left in some quarters in Afghanistan. However, stopping and correcting it now may provide some space for damage control

Government restrictions on capital export might not prove to be effective, given the high levels of corruption. Even low-income middle-class Afghans, who may have accumulated savings or sold their assets at reduced prices, will often resort to illegal means, including paying bribes at the border crossings, to move their money.

There is a likelihood that the inflow of aid for refugees will decrease and potentially cease altogether. If researchers were to conduct a study, they might find that Pakistan is losing more than it is gaining or saving. Whether it's aid or the private funds of Afghans, both have been significant contributors to Pakistan's economy. It's also important to calculate the impact of the millions who were previously purchasing various Pakistani products but may no longer do so, as this will have a substantial effect on Pakistan's economic health.

Finally, the policy, especially the method of its implementation, is contributing to the escalation of ethnic tensions in Pakistan, potentially reaching a dangerous level that could undermine the country's political stability. Instances of police and private individuals in Sindh and Punjab checking and harassing Pakistani Pashtuns are leading to growing resentment that could evolve into open conflicts. The arrests and deportations of some Pakistani Pashtuns are detrimental to the ethnic harmony of the state of Pakistan.

Moreover, the expression of racial slurs by some on social media is generating resentment, even among those Pashtuns who were otherwise non-committal about ethnic politics.

This policy, and its implementation, are implausible to assist Pakistan diplomatically. Pakistan might risk losing whatever little goodwill it had left in some quarters in Afghanistan. However, stopping and correcting it now may provide some space for damage control.