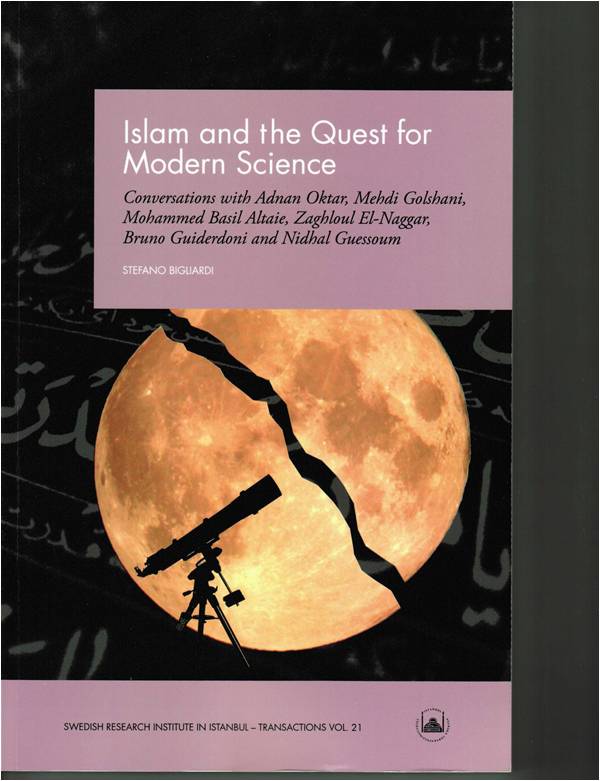

Modern Science

Stefano Bigliardi

Swedish Research Institute, Istanbul, 2014

Since the 1930s, one of the ideas to have taken root in the Islamic world is that Islam is not ‘just’ a religion, but also a system for organizing the individual and collective aspects of human life. This concept reaches further than what led to the elaborate categorization in the 8th to 10th centuries of human actions – mostly individual – into varieties of ‘permitted’ and ‘forbidden’ behaviour. The idea’s practical emphasis is, instead, on collective behaviours and policies. Thus, for example, a large body of literature has evolved on Islamic political and economic systems. In the same spirit, work on developing Islamic principles to guide scientific research started relatively late – in the latter half of the 20th century – and there are still only a few scholars that have engaged in this field. But their work has attracted scholarly attention with serious discussions emerging on the acquisition, interpretation, analysis and application of scientific knowledge.

Stefano Bigliardi’s book Islam and the Quest for Modern Science provides an up-to-date overview of this body of work. He has interviewed six major contemporary investigators of the relation between Islam and science. One of them, Adnan Oktar, aka Harun Yahya, is not a scientist by training, but has written prolifically on the subject. The remaining five are academics: Mehdi Golshani is an Iranian physicist with a Shiite background; Mohammed Basil Altaie, an Iraqi physicist teaching in Jordan, is a practicing Sufi; Bruno Guideroni, a French astrophysicist, is a convert to Islam and another practicing Sufi; Zaghloul El-Naggar is an Egyptian geologist; and Nidhal Guessoum is an Algerian physicist teaching in the UAE. The book contains interviews transcribed verbatim along with the background of the interlocutors. Its concluding chapter compares their responses and discusses the science-faith interaction generally.

Most of the scientists interviewed do not favour the idea of an "Islamic" science as distinct from that practiced by non-Muslims

In his foreword to the book, Leif Stenberg, the author of The Islamization of Science (1996), provides a useful context to Bigliardi’s work: Stenberg’s own book focused on four Muslim thinkers who had tried to harmonize science and Islam. He points out that, while this movement enjoyed wide popular appeal, it did not have much impact on the thinking of most of the scientists interviewed by Bigliardi.

Bigliardi uses an opportune set of questions to sample the spectrum of current Muslim views on science. The divergence of their answers is surprising, even among scientists working in similar fields, and the interplay of scientific thinking and faith – or faith with a tinge of mysticism – is revealing. Take, for example, the subject of miracles. Miracles clearly contravene the laws of nature. Can they be reconciled with science? Are natural laws suspended temporarily when a ‘miracle’ takes place? Are miracles allegories rather than facts? The interviewed scientists answer such questions very differently.

One says that the Quranic verses describing miracles may be among those that are categorized as being “of unclear meaning,” that is, they cannot be described, understood or explained with certainty. Others argue that miracles are cited metaphorically and are not intended to be events in the literal sense. Alternatively, a miracle constitutes a “spiritual experience” and thus not a physical event. Miracles might also be controlled by another set of laws of which we have no knowledge. Finally, miracles may be low-probability events that occur perhaps only once in the universe’s lifetime – scientific laws, specifically those of quantum mechanics, allow such events to happen.

One interlocutor feels that it may not be possible at all to explain miracles scientifically. He resorts to Gödel’s Theorem of mathematical logic, stating that physicists will not be able to explain all natural phenomena “[unless] the theorem is disproved, and in the last 80 years nobody has disproved it.”

This is one of the more sophisticated technical arguments presented and calls for some examination: Gödel’s Theorem, first proved in 1931, says that logical theories are limited in what they can prove. In particular, in any theory powerful enough to prove certain statements, there are other statements that can be neither proved nor disproved. Thus, in every theory, there will be true statements that cannot be proved. However, it does not follow that there are true statements that cannot be proved in any theory. Gödel’s Theorem is often confused with the latter incorrect claim and then used to derive further fallacies. Statements such as “nothing can be known for sure” are really philosophical speculations that are presented incorrectly as consequences of Gödel’s Theorem. The connection between miracles and the theorem, which the interlocutor is trying to make in Bigliardi’s book, borders on such misinterpretations. Moreover, trying to disprove Gödel’s Theorem is futile because it has been verified mechanically.

Most of the scientists interviewed do not favour the idea of an “Islamic science” as something distinct from the science practiced by non-Muslims, and maintain that the methodology and results of science have to be accepted alike by everyone. However, some interlocutors feel that Muslims may have a different understanding of scientific results, amounting to a “theistic interpretation.” For Muslim scientists influenced by Sufi doctrines, the interpretation might also have “mystical” and “allegorical” aspects. Most of them share the view that Islamic edicts imply that science should be applied responsibly. Obvious misapplications would, therefore, include weapons research and work on forbidden products.

Where some interlocutors’ opinions differ overwhelmingly from mainstream scientific views are, for instance, in certain areas of quantum mechanics – aspects, which they argue, are “inconsistent with religious beliefs” and “need to be reworked”! Others contend that scientific causality is useful only for ordering events chronologically. It is not “true causality” (i.e., does not furnish the “reason” that events occur as they do). Finally, some of the scientists interviewed accept the theory of evolution, but reject the random mutation mechanism – “since it would be too slow to explain the present life” – in favour of God-guided mutation.

The opinions compiled by Stenberg and Bigliardi are about three decades apart. During this short period, Muslim scientists’ attitude towards science seems to have changed substantially. In particular, it appears that the “Islamization of science” movement, so spirited when Stenberg gathered his data, has mellowed. In retrospect, the movement’s goals, such as “reconciling religion and science” and “developing religiously guided scientific methodologies” – principally formulated by general thinkers and not by practicing scientists – were unclear and un-pursuable. As a consequence, for instance, we see the tremendous shift from the idea that all knowledge is to be sought in the Quran to the idea that, to discover scientific laws, one has to study nature!

Among Muslim scientists, many are deeply concerned with the role Islam should play in science, but others hold the secularist outlook that scientific work and the scientist’s faith are independent and entirely separate. (After all, some of them argue, the scientists of the 8th–13th century “Islamic Golden Age” carried out scientific research free of any supra-scientific constraints.)

S. Kamal Abdali holds a PhD in computer science and has worked in the theoretical and foundational areas of the discipline