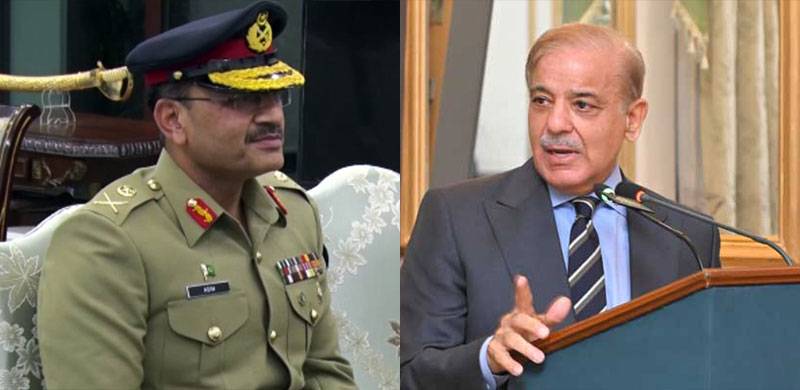

General (retired) Qamar Javed Bajwa handed over the command of the Pakistan army to its new chief, General Asim Munir. The ceremony ended one of the most controversial periods of civil-military strife in the country. The new army chief is expected to propose innovative and unorthodox strategies to reclaim the army’s reputation. The most serious challenge the military establishment must meet is to seek an apolitical role in national affairs.

Apparently, there is no easy way to achieve this daunting task.

The military establishment in any country, including the most developed countries such as the United States, is an integral part of national decision-making process. It is often dragged into political squabbles.

In the wake of the January 6 insurrection on Capitol Hill by the supporters of the then President Trump, Speaker Nancy Pelosi called the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley, and urged him to put in place additional measures to prevent the president from ordering a nuclear strike anywhere in the world or deploying armed forces domestically against his political rivals or constitutional processes. There is no denying the fact that the establishment played a role within the constitutional limits.

The political role of Pakistan Army is far more evident than many other armies around the world. It corresponds to the objective regional and extra-regional geostrategic conditions.

Pakistan is located in a strategically volatile region wherein any political development affects global peace and policies. Pakistan, in turn, has its own strategic interests in the region and beyond.

Throughout the history of Pakistan, strategic interests outweighed economic or diplomatic interests. Since 1979, the state of Pakistan has been involved in an active, though low-scale, warfare. Its national issues are predominantly of strategic nature. This overwhelmingness of the display of national power provides military an inevitable role in decision making processes that fall purely within the realm of politics. Consequently, inter-institutional balance in Pakistan leaning towards civilian supremacy and subordination of other stakeholders could not be created. Most importantly, recently no strategic paradigm shift has taken place in the region and beyond.

Domestically, Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) has ended ceasefire and announced fresh attacks across Pakistan. Regionally, Afghanistan is being governed by a feeble Taliban regime that is trying to subordinate impatient and destitute Afghans through a combination of terror and religious indoctrination. The Islamic State of Khorasan (IS-K), an outfit of ISIS, is challenging Taliban through subverting public peace and security. Kashmir dispute is alive and India-Pakistan relations have transformed from enmity to hatred.

The political turmoil in Iran, civil wars in the Middle East, war in Ukraine, and simmering great power tensions in South China Sea show that nothing has changed organically.

The global need of a strong Pakistan Army, at the cost of any other domestic institution, is as vital as it was about a year ago. This global need will inevitably ensure Pakistan military remains a strong political force in the country.

Additionally, throughout history, Pakistan military has been a political player, acting more like a political arbitrator. For more than three decades, it directly governed the country through the Martial Laws. When out of direct power, it maneuvered and engineered governmental changes in the centre and provinces. It calved political leaders, created electoral alliances, forcibly decomposed some others, provided public coffers to its political darlings, and exiled, hanged or killed stubborn defiants.

The military establishment of Pakistan has served, promoted, and consolidated an exclusive and dominating role for itself in national security, economy, and development.

It has developed stakes in civilian sectors such as banking, power generation, real estate, education, healthcare, and food production and products. Its genetics are so designed that an abrupt withdrawal from the political sphere would destroy military as well as national interests.

A power vacuum created by its announced sudden withdrawal from politics is indigestible to political parties across the spectrum. For Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, it meant a compromise over corruption in politics. A foreign-born conspiracy, it believed, hatched in Sindh House Islamabad where a naked use of money bribed lawmakers to switch their allegiance from the PTI to other parties. It left Imran Khan with nothing else but to enter into an unrelenting marathon of political mobilization, naming apolitical military leadership as ‘animals’ and berating its intentions as betrayal to the people and the state of Pakistan. Unexpectedly, for the first time in the history of Pakistan, a political leader has brought military establishment to a defensive position. Arguably, Imran Khan’s narrative succeeded in penetrating throughout Pakistan, leaving military establishment with fewer options besides the use of state power to arrest and silence its leaders.

For the military establishment, its institutional interests are of paramount significance. The issue is that they cannot be served satisfactorily in the presence of a strong parliament populated by popular political leadership. For example, after its volunteer political defanging, will military leadership submit to civilian oversight of its affairs? Will it sacrifice the byproduct of its political maneuvering power – its competitive advantage in commercial sectors?

The real question politics in Pakistan faces is that how, in the presence of a hugely powerful institution like the military, other institutions can flourish and cut it to its size effectively. It could have been possible had there been a consensus among political leaders. The fact is that national political ambiance is acrimonious and vindictive.

Moreover, leading macroeconomic indicators are showing a downfall, and political conflict is worsening them. Pakistan’s national problems will not solve with a new general election or with a mere announcement of withdrawal of military from politics.

The current phase of civil-military conflict in Pakistan will continue unless national leadership – both civil and military – enter into a new constitutional arrangement, declare parliament as the supreme institution, bring the military effectively under civilian control, limit powers of judiciary to interfere in executive affairs, introduce and enforce stringent anti-corruption laws, and agree to a long-term national plan of action on economy.

Unfortunately, if the military sticks to its current intention of a mere announcement of its withdrawal from politics, no honest broker can be found in the country to bring the stakeholders to an agreeable resolution of their disagreements. Therefore, one can say that this instability will continue for a foreseeable future.

Apparently, there is no easy way to achieve this daunting task.

The military establishment in any country, including the most developed countries such as the United States, is an integral part of national decision-making process. It is often dragged into political squabbles.

In the wake of the January 6 insurrection on Capitol Hill by the supporters of the then President Trump, Speaker Nancy Pelosi called the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley, and urged him to put in place additional measures to prevent the president from ordering a nuclear strike anywhere in the world or deploying armed forces domestically against his political rivals or constitutional processes. There is no denying the fact that the establishment played a role within the constitutional limits.

The political role of Pakistan Army is far more evident than many other armies around the world. It corresponds to the objective regional and extra-regional geostrategic conditions.

Pakistan is located in a strategically volatile region wherein any political development affects global peace and policies. Pakistan, in turn, has its own strategic interests in the region and beyond.

Throughout the history of Pakistan, strategic interests outweighed economic or diplomatic interests. Since 1979, the state of Pakistan has been involved in an active, though low-scale, warfare. Its national issues are predominantly of strategic nature. This overwhelmingness of the display of national power provides military an inevitable role in decision making processes that fall purely within the realm of politics. Consequently, inter-institutional balance in Pakistan leaning towards civilian supremacy and subordination of other stakeholders could not be created. Most importantly, recently no strategic paradigm shift has taken place in the region and beyond.

Domestically, Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) has ended ceasefire and announced fresh attacks across Pakistan. Regionally, Afghanistan is being governed by a feeble Taliban regime that is trying to subordinate impatient and destitute Afghans through a combination of terror and religious indoctrination. The Islamic State of Khorasan (IS-K), an outfit of ISIS, is challenging Taliban through subverting public peace and security. Kashmir dispute is alive and India-Pakistan relations have transformed from enmity to hatred.

The political turmoil in Iran, civil wars in the Middle East, war in Ukraine, and simmering great power tensions in South China Sea show that nothing has changed organically.

The global need of a strong Pakistan Army, at the cost of any other domestic institution, is as vital as it was about a year ago. This global need will inevitably ensure Pakistan military remains a strong political force in the country.

The civil-military conflict will continue until leaders reach a new constitutional arrangement in Pakistan

Additionally, throughout history, Pakistan military has been a political player, acting more like a political arbitrator. For more than three decades, it directly governed the country through the Martial Laws. When out of direct power, it maneuvered and engineered governmental changes in the centre and provinces. It calved political leaders, created electoral alliances, forcibly decomposed some others, provided public coffers to its political darlings, and exiled, hanged or killed stubborn defiants.

The military establishment of Pakistan has served, promoted, and consolidated an exclusive and dominating role for itself in national security, economy, and development.

It has developed stakes in civilian sectors such as banking, power generation, real estate, education, healthcare, and food production and products. Its genetics are so designed that an abrupt withdrawal from the political sphere would destroy military as well as national interests.

A power vacuum created by its announced sudden withdrawal from politics is indigestible to political parties across the spectrum. For Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, it meant a compromise over corruption in politics. A foreign-born conspiracy, it believed, hatched in Sindh House Islamabad where a naked use of money bribed lawmakers to switch their allegiance from the PTI to other parties. It left Imran Khan with nothing else but to enter into an unrelenting marathon of political mobilization, naming apolitical military leadership as ‘animals’ and berating its intentions as betrayal to the people and the state of Pakistan. Unexpectedly, for the first time in the history of Pakistan, a political leader has brought military establishment to a defensive position. Arguably, Imran Khan’s narrative succeeded in penetrating throughout Pakistan, leaving military establishment with fewer options besides the use of state power to arrest and silence its leaders.

For the military establishment, its institutional interests are of paramount significance. The issue is that they cannot be served satisfactorily in the presence of a strong parliament populated by popular political leadership. For example, after its volunteer political defanging, will military leadership submit to civilian oversight of its affairs? Will it sacrifice the byproduct of its political maneuvering power – its competitive advantage in commercial sectors?

The real question politics in Pakistan faces is that how, in the presence of a hugely powerful institution like the military, other institutions can flourish and cut it to its size effectively. It could have been possible had there been a consensus among political leaders. The fact is that national political ambiance is acrimonious and vindictive.

Moreover, leading macroeconomic indicators are showing a downfall, and political conflict is worsening them. Pakistan’s national problems will not solve with a new general election or with a mere announcement of withdrawal of military from politics.

The current phase of civil-military conflict in Pakistan will continue unless national leadership – both civil and military – enter into a new constitutional arrangement, declare parliament as the supreme institution, bring the military effectively under civilian control, limit powers of judiciary to interfere in executive affairs, introduce and enforce stringent anti-corruption laws, and agree to a long-term national plan of action on economy.

Unfortunately, if the military sticks to its current intention of a mere announcement of its withdrawal from politics, no honest broker can be found in the country to bring the stakeholders to an agreeable resolution of their disagreements. Therefore, one can say that this instability will continue for a foreseeable future.