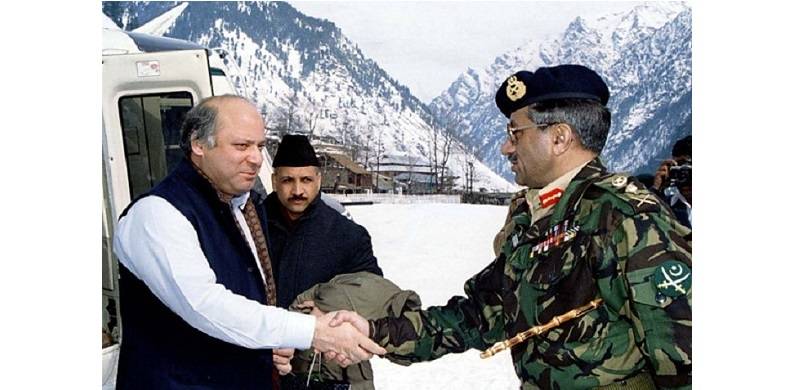

On his watch, the Pakistani army decided to attack Indian positions at Kargil, Kashmir, in the spring of 1999. He acted on his own volition. Why would he need to consult with the civilian government? After all, he was the army chief and Pakistan was a Praetorian State.

That invasion was a disaster militarily. Initially, it was portrayed as an indigenous Kashmiri operation, being waged by freedom fighters. Later, it became obvious that the Pakistan army had carried it out.

It brought opprobrium on Pakistan. Even China, Pakistan’s all-weather friend and much else, did not support it. The withdrawal was disgraceful.

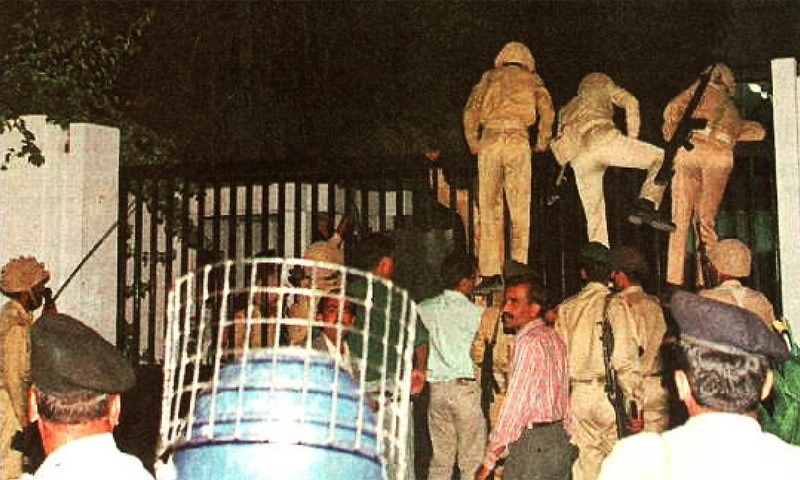

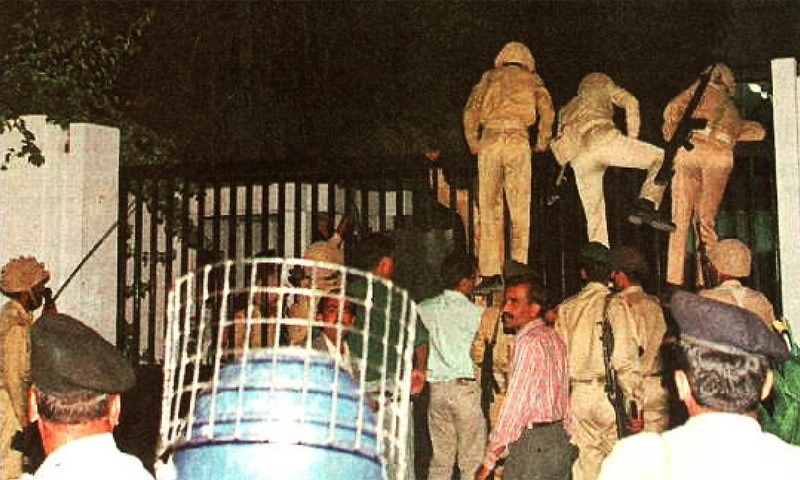

His honour had been questioned. His anger came to fruition when he overthrew the civilian government in October 1999.

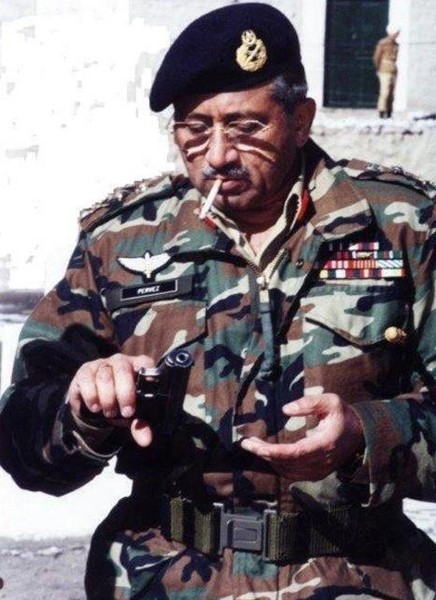

He declared himself the Chief Executive, a new position intended to distinguish himself from prior army chiefs who had seized power illegally and declared themselves as Chief Martial Law Administrators. He was going to bring Enlightened Moderation to the country, he promised.

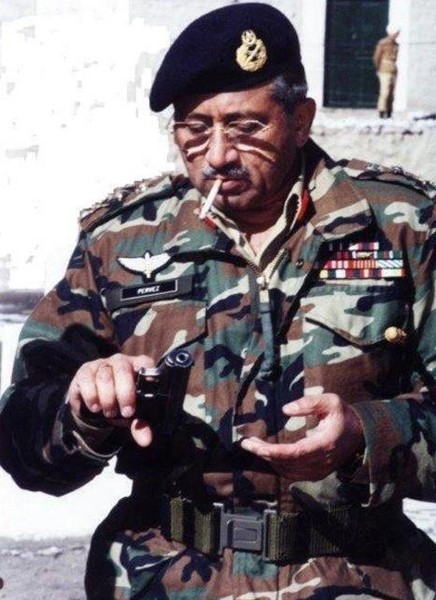

He told a British reporter, “It’s a good feeling to be in charge.”

Whenever his decision to carry out the coup that had put him in power was questioned, he would resort to a medical metaphor: “Sometimes you have to cut off the arm to save the body.” Like Generals Ayub, Yahya and Zia, he viewed himself as the savior of the country, indispensable for its survival and growth.

Whenever his decision to carry out the coup that had put him in power was questioned, he would resort to a medical metaphor: “Sometimes you have to cut off the arm to save the body.” Like Generals Ayub, Yahya and Zia, he viewed himself as the savior of the country, indispensable for its survival and growth.

In a few years, he promoted himself to President, saying the title was necessary since he was heading to India to negotiate a resolution to the Kashmir Problem with the Indian Prime Minister. Just when a settlement was in hand, his ego overwhelmed him and he left India in a huff and a puff. To this day, the issue is unresolved.

On the Afghan border, where the Americans were engaged in a full-scale war with the Taliban and their remnants, he vigorously supported what had now become the infamous “War on Terror.” He bonded well with President George W. Bush and relished the White House photo-ops.

He kept reminding the Americans - and the West, more broadly speaking - that even though he was a military dictator, they should support him because if he was removed from office, Pakistan would be plunged into crisis. He was evoking memories of what Louis XV of France had said, "Après moi, le déluge (after me comes the deluge)."

During his tenure, whenever he would be asked about the debacle of 1971, he would dismiss the question derisively, saying "why should we worry about something that happened decades ago." The fact that half of the country seceded from Pakistan in 1971, bringing untold humiliation to Pakistan and its army, and raising doubts about the Two Nation Theory on which the nation was founded, did not seem to bother him.

As a military man, the memory of that crushing defeat must have haunted him for years. He just did not want to admit it publicly, nor did he want to apologise to the people of Bangladesh for the atrocities committed against them by the army, even if that meant that Pakistan would be unable to resume friendly relations with Bangladesh.

When a woman, Mukhtaran Mai, was gang-raped, he did his best to cover it up. He was incensed when the topic came up during an overseas visit. He criticised her for speaking with international media, saying it was going to damage the image of the country.

At the start, Musharraf was welcomed at home by a nation weary of ineffective and corrupt democratic leaders, but condemned internationally for deposing an elected government. This duality reversed itself after 11 September 2001. Musharraf’s bold response to this tragedy solidified his position in the West just as surely as it began to create domestic disenchantment with his rule.

For years, he would remain the darling of the West, which continued to shower him with accolades and contributed billions of dollars of financial and economic assistance to his government. At home, he continued to fight a crisis of legitimacy, brought on nominally by his volte face on the uniform issue.

Musharraf’s domestic crisis was exacerbated by his unwillingness to share power with any independent civilian group. He displayed no signs of exiting the stage. By overstaying his welcome, he alienated himself from the liberal segments of Pakistani society, his battle call for enlightened moderation notwithstanding. His close affiliation with the foreign policy of the Bush administration, which caused him to pursue the counter-insurgency campaign in Waziristan, alienated the conservative segments.

All along, and specifically in a manner reminiscent of Ayub, he claimed to have done more for democracy than any prior leader. He was trapped in the Dictator’s Paradox: the more authority he claimed, the less power he wielded. What had worked for him on the battlefield failed him on the political field.

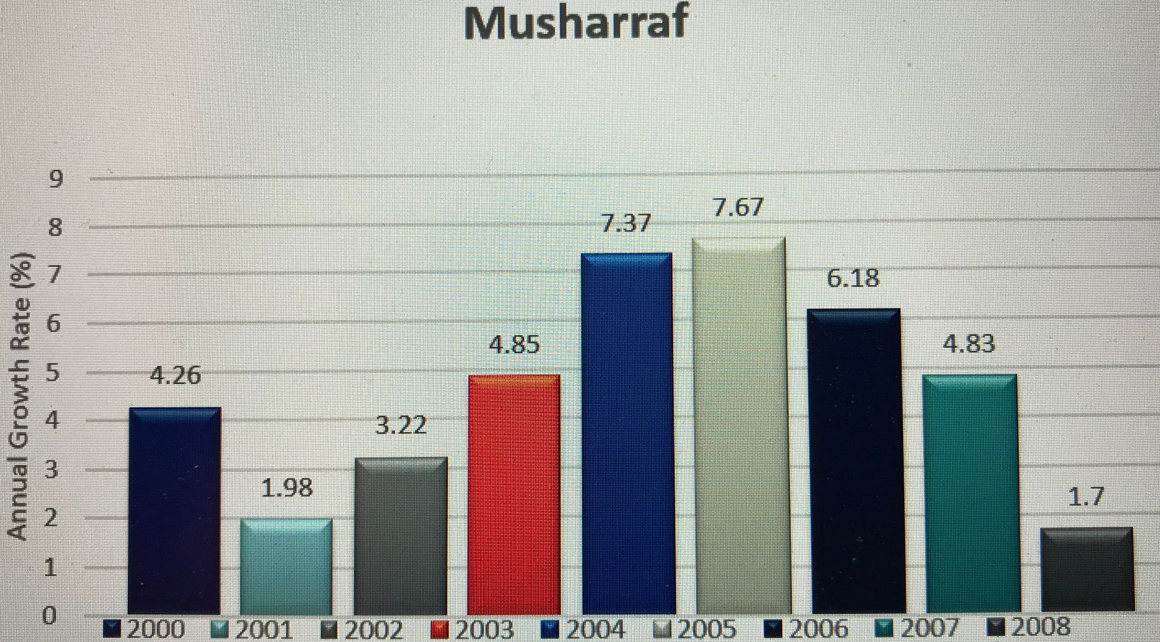

Of course, there was a silver lining for him in the dark clouds. The positive developments on the macroeconomic front in the first few years, brought on largely by US-sponsored economic aid and private investments from the Persian Gulf region, won over certain segments of society to him. Confident about his place in history, the general even published a memoir whose title In the Line of Fire was stolen from a movie by Clint Eastwood.

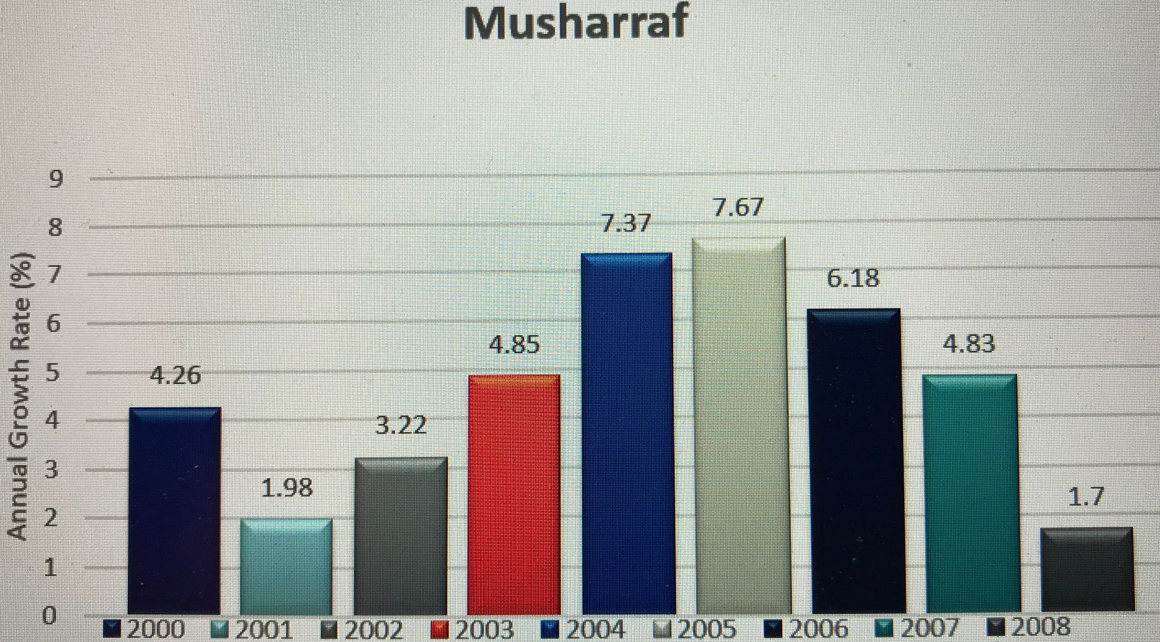

The economic picture was not as rosy as he made it out to be. Even during the best years, the growth rate did not exceed eight percent. It began a steady decline after 2005 and had fallen to less than two percent by the time he quit.

Undeterred, Musharraf created a presidential website to showcase his achievements. The site also acted as a portal for the government of Pakistan, confirming that he was not only the head of state but also the head of government in addition to being the army chief.

General Musharraf’s eight years in office were in many ways evocative of Coriolanus, a military and political leader of ancient Rome. Born Caius Marcius into a rich and famous family, he earned the title "Coriolanus" after a major victory at Corioli in 493 B.C. against the Volscians, a neighboring tribe of Rome.

Around the year 1600, William Shakespeare dramatised the life of Coriolanus in a play that T. S. Eliot said was Shakespeare’s finest tragedy. Coriolanus as a prideful general is the least sympathetic protagonist among Shakespeare’s tragic figures.

The play Shakespeare depicts a society undergoing tumultuous change, struggling to adjust to a new form of government. Until recently, Rome was ruled by a king and the people had no independent voice. Now, in the early years of the republic, they participate in the election of consuls. Tribunes, representing their interests, defend them against abuses of power.

One of the play’s main characters, an aristocrat named Menenius, compares the state to a human body in which different classes of society are its parts. The aristocrats are the 'belly' and the lower-class commoners are the 'toe.' Coriolanus, as a fierce, noble and proud military leader, represents the 'arms' of the Roman state.

General Coriolanus dominates the play, just as General Musharraf once dominated Pakistan’s political stage. Both are men of action whose physical strength and courage are legendary. Coriolanus is perhaps the greatest warrior of his age. It was said that Musharraf’s personal heroism inspired other soldiers and men willingly follow him into battle. But like Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, he was not a natural leader.

In the denouement of Shakespeare’s play, after failing to persuade Romans to align them with his rule, Coriolanus turns against Rome and is banished. In the ultimate irony, he joins the Volscians and makes war on Rome. However, his mother persuades him to call off the attack, which enrages the Volscians under Aufidius so much that they kill him. To paraphrase Aufidius, the virtues of war had become the vices of peace for the man on horseback. Dismounted, he was a sorry creature.

In the denouement of Shakespeare’s play, after failing to persuade Romans to align them with his rule, Coriolanus turns against Rome and is banished. In the ultimate irony, he joins the Volscians and makes war on Rome. However, his mother persuades him to call off the attack, which enrages the Volscians under Aufidius so much that they kill him. To paraphrase Aufidius, the virtues of war had become the vices of peace for the man on horseback. Dismounted, he was a sorry creature.

Coriolanus approximates the tragic heroes of an ancient Greek drama, a great man who is brought low by his hubris. Overriding egoism can only terminate in desolation, as Plato said. Such an ego prevented Musharraf from developing an exit strategy since he was convinced of his indispensability.

Shakespeare endowed his central character with a deeper flaw in the form of a pathological dependency upon his mother. As she reminds him in two pivotal scenes, he is her creation. In the end, Coriolanus cannot simply sever himself from the body politic of his motherland, for his identity depends upon his mother’s esteem.

General Musharraf was a creature of the army, which was his “mother.” The nine Corps Commanders, symbolising this mother, lurked in the background and appeared on stage whenever major decisions were being made.

Towards the end of his tenure, Musharraf mishandled the crisis at the Red Mosque, mounted failed military operations in Baluchistan and KP, and created a wide assortment of enemies after prominent figures such as Nawab Bugti were killed in Baluchistan. He failed to end terror.

Indeed, his policies backfired, and created the Pakistani Taliban which remain active to this day. On his watch, they killed former Prime Minister Bhutto in Rawalpindi after she was returning from a large rally.

In November 2007, he gave himself another five-year term as president and stepped down as the army chief, six years past his retirement date from the army.

When the country’s Supreme Court objected, he removed the Chief Justice and several other judges, declared a state of emergency on November 3 and suspended the constitution. Police arrested thousands of protesters, including a quarter of the nation’s lawyers.

After the declaration of a state of emergency, even the US backed off from him. The Commonwealth suspended Pakistan’s membership. He was no longer seen as the Enlightened Moderate, the mantle he had given himself.

Why did he impose the emergency? There was no cross-border threat. Arresting the judges of the Supreme Court and the attorneys who marched to support them was not going to bring peace to the cities. And if they were the problem to begin with, why were they released in just a couple of weeks?

The emergency was supposedly imposed to rid the nation of the scourge of terrorism. But there was no evidence that imposing it would solve the problem. It was not a national emergency but a personal one designed to secure the presidency for one man.

After he declared the emergency, the International Republican Institute released a survey of Pakistani public opinion that showed that two-thirds of Pakistanis wanted Musharraf to resign, and a majority wanted the army out of politics. In late November, in an unprecedented act, about two dozen retired senior military officers called upon him to restore the justices of the Supreme Court and to release all political prisoners.

In the end, even the Corps Commanders distanced themselves from him. They had prevailed upon Musharraf to change his mind about the uniform. For years he had refused to take it off, saying openly that it was his “second skin.”

It was no longer there to protect him. The world collapsed around him and he was forced to step down from office.

After he was deposed, unceremoniously and ignominiously, he lived at various times in the UK and the UAE and was a frequent visitor to the US, grandstanding at packed auditoriums, giving the same speech over and over again, and making off with a hundred thousand dollars every time. It did not matter to him that he was speaking sometimes at small colleges in the Midwest to audiences that did not even know where Pakistan was located. All that mattered to him was fame, glory and money.

Pakistan’s national interest is best conceptualized and served by popularly elected civilians, not by any Coriolanus. Unless strong civilian institutions can be allowed to develop, Pakistan will return to be ruled by strong men whose lives will echo those of history’s tragic characters.

In 2003, at the peak of his power, he was touring the US. I got to hear him twice in one day in Los Angeles. Over breakfast at a famous hotel on the Avenue of the Stars, he sought to convince an audience consisting mostly of US business executives that Pakistan was the best place in which to invest their funds. When a Pakistani asked why he had failed to secure Kashmir, he refused to answer the question. When another Pakistani got up to present him with a book, he refused to take it. It was tossed into the recycling bin in front of everyone.

In the evening, he spoke to some one thousand Pakistanis over dinner at the swank Beverly Hotel. For reasons best known to him, the entire speech was delivered in English but a couple of sentences were delivered in Urdu.

He said that people kept asking him as to why the US is only giving a billion dollars to Pakistan. He said, tellingly in Urdu, “Take whatever money they are giving you. It’s free.” Did he hope to bond with the entirely Pakistani audience by speaking in the national language? Or did he think that the Americans did not understand Urdu?

A female doctor who was sitting on our table had been his neighbour a long time ago. During the break, she went to the dais to talk to him. As expected, she was allowed to speak to him by the security personnel. Musharraf did not even bother to look at her. She came back and said that the general will answer questions at the end.

But, as he was finishing his speech, he said the hotel had informed him that the room had to be returned to them. How was that possible, to tell a visiting head of state that he had to leave the room? It was not just the female doctor who was frustrated with his decision to not have an open dialogue with the audience.

That invasion was a disaster militarily. Initially, it was portrayed as an indigenous Kashmiri operation, being waged by freedom fighters. Later, it became obvious that the Pakistan army had carried it out.

It brought opprobrium on Pakistan. Even China, Pakistan’s all-weather friend and much else, did not support it. The withdrawal was disgraceful.

His honour had been questioned. His anger came to fruition when he overthrew the civilian government in October 1999.

He declared himself the Chief Executive, a new position intended to distinguish himself from prior army chiefs who had seized power illegally and declared themselves as Chief Martial Law Administrators. He was going to bring Enlightened Moderation to the country, he promised.

He told a British reporter, “It’s a good feeling to be in charge.”

Whenever his decision to carry out the coup that had put him in power was questioned, he would resort to a medical metaphor: “Sometimes you have to cut off the arm to save the body.” Like Generals Ayub, Yahya and Zia, he viewed himself as the savior of the country, indispensable for its survival and growth.

Whenever his decision to carry out the coup that had put him in power was questioned, he would resort to a medical metaphor: “Sometimes you have to cut off the arm to save the body.” Like Generals Ayub, Yahya and Zia, he viewed himself as the savior of the country, indispensable for its survival and growth.In a few years, he promoted himself to President, saying the title was necessary since he was heading to India to negotiate a resolution to the Kashmir Problem with the Indian Prime Minister. Just when a settlement was in hand, his ego overwhelmed him and he left India in a huff and a puff. To this day, the issue is unresolved.

On the Afghan border, where the Americans were engaged in a full-scale war with the Taliban and their remnants, he vigorously supported what had now become the infamous “War on Terror.” He bonded well with President George W. Bush and relished the White House photo-ops.

He kept reminding the Americans - and the West, more broadly speaking - that even though he was a military dictator, they should support him because if he was removed from office, Pakistan would be plunged into crisis. He was evoking memories of what Louis XV of France had said, "Après moi, le déluge (after me comes the deluge)."

During his tenure, whenever he would be asked about the debacle of 1971, he would dismiss the question derisively, saying "why should we worry about something that happened decades ago." The fact that half of the country seceded from Pakistan in 1971, bringing untold humiliation to Pakistan and its army, and raising doubts about the Two Nation Theory on which the nation was founded, did not seem to bother him.

As a military man, the memory of that crushing defeat must have haunted him for years. He just did not want to admit it publicly, nor did he want to apologise to the people of Bangladesh for the atrocities committed against them by the army, even if that meant that Pakistan would be unable to resume friendly relations with Bangladesh.

When a woman, Mukhtaran Mai, was gang-raped, he did his best to cover it up. He was incensed when the topic came up during an overseas visit. He criticised her for speaking with international media, saying it was going to damage the image of the country.

At the start, Musharraf was welcomed at home by a nation weary of ineffective and corrupt democratic leaders, but condemned internationally for deposing an elected government. This duality reversed itself after 11 September 2001. Musharraf’s bold response to this tragedy solidified his position in the West just as surely as it began to create domestic disenchantment with his rule.

When a Pakistani asked why he had failed to secure Kashmir, he refused to answer the question. When another Pakistani got up to present him with a book, he refused to take it. It was tossed into the recycling bin in front of everyone

For years, he would remain the darling of the West, which continued to shower him with accolades and contributed billions of dollars of financial and economic assistance to his government. At home, he continued to fight a crisis of legitimacy, brought on nominally by his volte face on the uniform issue.

Musharraf’s domestic crisis was exacerbated by his unwillingness to share power with any independent civilian group. He displayed no signs of exiting the stage. By overstaying his welcome, he alienated himself from the liberal segments of Pakistani society, his battle call for enlightened moderation notwithstanding. His close affiliation with the foreign policy of the Bush administration, which caused him to pursue the counter-insurgency campaign in Waziristan, alienated the conservative segments.

All along, and specifically in a manner reminiscent of Ayub, he claimed to have done more for democracy than any prior leader. He was trapped in the Dictator’s Paradox: the more authority he claimed, the less power he wielded. What had worked for him on the battlefield failed him on the political field.

Of course, there was a silver lining for him in the dark clouds. The positive developments on the macroeconomic front in the first few years, brought on largely by US-sponsored economic aid and private investments from the Persian Gulf region, won over certain segments of society to him. Confident about his place in history, the general even published a memoir whose title In the Line of Fire was stolen from a movie by Clint Eastwood.

The economic picture was not as rosy as he made it out to be. Even during the best years, the growth rate did not exceed eight percent. It began a steady decline after 2005 and had fallen to less than two percent by the time he quit.

Undeterred, Musharraf created a presidential website to showcase his achievements. The site also acted as a portal for the government of Pakistan, confirming that he was not only the head of state but also the head of government in addition to being the army chief.

General Musharraf’s eight years in office were in many ways evocative of Coriolanus, a military and political leader of ancient Rome. Born Caius Marcius into a rich and famous family, he earned the title "Coriolanus" after a major victory at Corioli in 493 B.C. against the Volscians, a neighboring tribe of Rome.

Around the year 1600, William Shakespeare dramatised the life of Coriolanus in a play that T. S. Eliot said was Shakespeare’s finest tragedy. Coriolanus as a prideful general is the least sympathetic protagonist among Shakespeare’s tragic figures.

The play Shakespeare depicts a society undergoing tumultuous change, struggling to adjust to a new form of government. Until recently, Rome was ruled by a king and the people had no independent voice. Now, in the early years of the republic, they participate in the election of consuls. Tribunes, representing their interests, defend them against abuses of power.

One of the play’s main characters, an aristocrat named Menenius, compares the state to a human body in which different classes of society are its parts. The aristocrats are the 'belly' and the lower-class commoners are the 'toe.' Coriolanus, as a fierce, noble and proud military leader, represents the 'arms' of the Roman state.

General Coriolanus dominates the play, just as General Musharraf once dominated Pakistan’s political stage. Both are men of action whose physical strength and courage are legendary. Coriolanus is perhaps the greatest warrior of his age. It was said that Musharraf’s personal heroism inspired other soldiers and men willingly follow him into battle. But like Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, he was not a natural leader.

In the denouement of Shakespeare’s play, after failing to persuade Romans to align them with his rule, Coriolanus turns against Rome and is banished. In the ultimate irony, he joins the Volscians and makes war on Rome. However, his mother persuades him to call off the attack, which enrages the Volscians under Aufidius so much that they kill him. To paraphrase Aufidius, the virtues of war had become the vices of peace for the man on horseback. Dismounted, he was a sorry creature.

In the denouement of Shakespeare’s play, after failing to persuade Romans to align them with his rule, Coriolanus turns against Rome and is banished. In the ultimate irony, he joins the Volscians and makes war on Rome. However, his mother persuades him to call off the attack, which enrages the Volscians under Aufidius so much that they kill him. To paraphrase Aufidius, the virtues of war had become the vices of peace for the man on horseback. Dismounted, he was a sorry creature.Coriolanus approximates the tragic heroes of an ancient Greek drama, a great man who is brought low by his hubris. Overriding egoism can only terminate in desolation, as Plato said. Such an ego prevented Musharraf from developing an exit strategy since he was convinced of his indispensability.

Shakespeare endowed his central character with a deeper flaw in the form of a pathological dependency upon his mother. As she reminds him in two pivotal scenes, he is her creation. In the end, Coriolanus cannot simply sever himself from the body politic of his motherland, for his identity depends upon his mother’s esteem.

General Musharraf was a creature of the army, which was his “mother.” The nine Corps Commanders, symbolising this mother, lurked in the background and appeared on stage whenever major decisions were being made.

Towards the end of his tenure, Musharraf mishandled the crisis at the Red Mosque, mounted failed military operations in Baluchistan and KP, and created a wide assortment of enemies after prominent figures such as Nawab Bugti were killed in Baluchistan. He failed to end terror.

Indeed, his policies backfired, and created the Pakistani Taliban which remain active to this day. On his watch, they killed former Prime Minister Bhutto in Rawalpindi after she was returning from a large rally.

In November 2007, he gave himself another five-year term as president and stepped down as the army chief, six years past his retirement date from the army.

When the country’s Supreme Court objected, he removed the Chief Justice and several other judges, declared a state of emergency on November 3 and suspended the constitution. Police arrested thousands of protesters, including a quarter of the nation’s lawyers.

After the declaration of a state of emergency, even the US backed off from him. The Commonwealth suspended Pakistan’s membership. He was no longer seen as the Enlightened Moderate, the mantle he had given himself.

Why did he impose the emergency? There was no cross-border threat. Arresting the judges of the Supreme Court and the attorneys who marched to support them was not going to bring peace to the cities. And if they were the problem to begin with, why were they released in just a couple of weeks?

The emergency was supposedly imposed to rid the nation of the scourge of terrorism. But there was no evidence that imposing it would solve the problem. It was not a national emergency but a personal one designed to secure the presidency for one man.

After he declared the emergency, the International Republican Institute released a survey of Pakistani public opinion that showed that two-thirds of Pakistanis wanted Musharraf to resign, and a majority wanted the army out of politics. In late November, in an unprecedented act, about two dozen retired senior military officers called upon him to restore the justices of the Supreme Court and to release all political prisoners.

In the end, even the Corps Commanders distanced themselves from him. They had prevailed upon Musharraf to change his mind about the uniform. For years he had refused to take it off, saying openly that it was his “second skin.”

It was no longer there to protect him. The world collapsed around him and he was forced to step down from office.

After he was deposed, unceremoniously and ignominiously, he lived at various times in the UK and the UAE and was a frequent visitor to the US, grandstanding at packed auditoriums, giving the same speech over and over again, and making off with a hundred thousand dollars every time. It did not matter to him that he was speaking sometimes at small colleges in the Midwest to audiences that did not even know where Pakistan was located. All that mattered to him was fame, glory and money.

Pakistan’s national interest is best conceptualized and served by popularly elected civilians, not by any Coriolanus. Unless strong civilian institutions can be allowed to develop, Pakistan will return to be ruled by strong men whose lives will echo those of history’s tragic characters.

In 2003, at the peak of his power, he was touring the US. I got to hear him twice in one day in Los Angeles. Over breakfast at a famous hotel on the Avenue of the Stars, he sought to convince an audience consisting mostly of US business executives that Pakistan was the best place in which to invest their funds. When a Pakistani asked why he had failed to secure Kashmir, he refused to answer the question. When another Pakistani got up to present him with a book, he refused to take it. It was tossed into the recycling bin in front of everyone.

In the evening, he spoke to some one thousand Pakistanis over dinner at the swank Beverly Hotel. For reasons best known to him, the entire speech was delivered in English but a couple of sentences were delivered in Urdu.

He said that people kept asking him as to why the US is only giving a billion dollars to Pakistan. He said, tellingly in Urdu, “Take whatever money they are giving you. It’s free.” Did he hope to bond with the entirely Pakistani audience by speaking in the national language? Or did he think that the Americans did not understand Urdu?

A female doctor who was sitting on our table had been his neighbour a long time ago. During the break, she went to the dais to talk to him. As expected, she was allowed to speak to him by the security personnel. Musharraf did not even bother to look at her. She came back and said that the general will answer questions at the end.

But, as he was finishing his speech, he said the hotel had informed him that the room had to be returned to them. How was that possible, to tell a visiting head of state that he had to leave the room? It was not just the female doctor who was frustrated with his decision to not have an open dialogue with the audience.