As a nine year child, my father told me the power of prayer. “A child was born to a school teacher who would not speak till the age of nine. He was taken to an elder, pious and religious man – soliciting his opinion, and requesting him to echo and reinforce personal prayers. The elder prayed and foretold that God willing, the boy would one day speak so loudly the world would listen to him.”

That was my first encounter with Dr Salam in absentia.

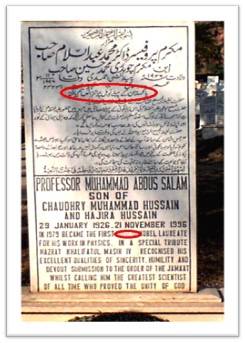

In Rabwah (Chenab Nagar) stands a prestigious six-storey complex, the Tahir Heart Institute. It is a not-for-profit, partly charitable hospital, for the poor and needy in the most impoverished region of Punjab, Pakistan. From the sixth floor, towards east, one can see the Bahishti Maqbara, the graveyard where Dr Salam lies buried alongside his parents – a cemetery reserved for those who had contributed a minimum tenth of their annual income for the service of faith. A two-minute walk takes you to the grave of an international figure, the greatest Pakistani scientist that the world had known. His tombstone was once inscribed “Abdus Salam, the First Muslim Nobel Laureate.”

Soon the grave was visited by government functionaries and the inscription erased partly, so as to absurdly read “Abdus Salam, the First ….. Nobel Laureate.”

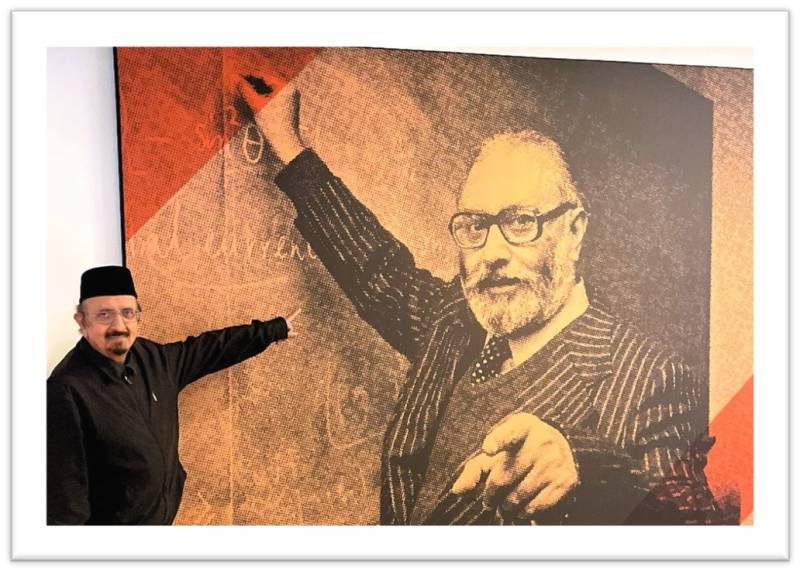

Dr Abdus Salam received the Nobel Prize in 1979. I, along with my father, visited him in December 1979 at his Campion Road, Putney residence. We were prepared to be awed by the man, by the loftiness of his stature as a scientist. As I rang the bell, a bespectacled beard transmuted in silver, and a smiling man in a woollen cap ushered us inside a room. As we first saw him, he looked imposing, but it was his eyes that proclaimed his genius. And they transformed an otherwise stern face and made it gentle, kindly, affectionate. The room had shelves with a large collection of books; on science, literature, religion and the Holy Quran. We were asked to sit on the chairs while Dr Salam sat on the carpet in front of us, partly reclining and supporting himself on a pillow.

After exchanging initial pleasantries, I asked, “Sir, what was the inspiration behind the Nobel Prize?” Without uttering a word, he raised his left hand and pointed towards the shelf containing copies of the Holy Quran. With that, he effervesced. His smile grew large like the sun. His eyes radiated with joy. He lifted his hands as if impatient to tell a story. He spoke on a recondite subject, the unification theory, but he made it understandable to me – even though I was not conversant with advanced physics and mathematics. Summing up, he said, “One search has reached the quark level. Perhaps there is yet another step and yet another until there will remain just one single stuff of which all matter is made.” His quest had been for unity, beauty and simplicity.

Dr NM Butt, Professor Emeritus and Chairman of the Pakistan Science Foundation told me in one of our meetings, “I was in Trieste when Dr Salam received the Nobel Prize. In his honour, the entire city was lit up at night to celebrate their prodigy. It was a spectacular event, most awe-inspiring!”

Over the next hour, I learned about the developed electroweak theory that unifies two of the four fundamental forces that led to his Nobel Prize. When asked if his religious views made him think about this unification, he chuckled and said “One eighth of Holy Quran exhorts the believers to study nature and to find the signs of God in the phenomenon of nature. So Islam has no conflict with science.”

He talked of scientific history, Muslim contribution to science, international relations and his controlled fury – ‘cosmic anger’ – about the injustice of a world where lack of opportunity can handicap even the most gifted student, and his indignation at the decline of science in the heritage of Islam. Salam did not, of course, regard himself as a holy man. As a pilgrim on the road to science, he was, as “humble as dust and ashes.” During this hour, I luxuriated in the cadence of his voice. His influence on me had been transcendent. My fascination for him had evolved into a reflection on archetypal virtue.

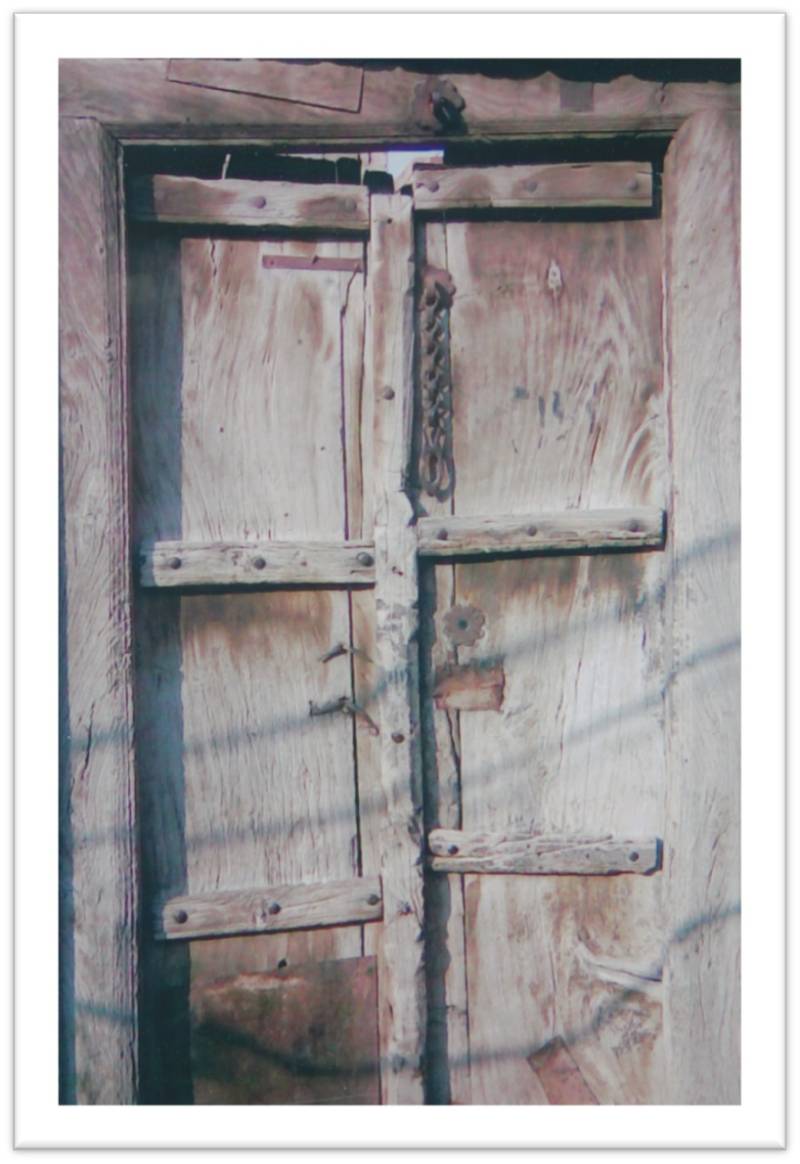

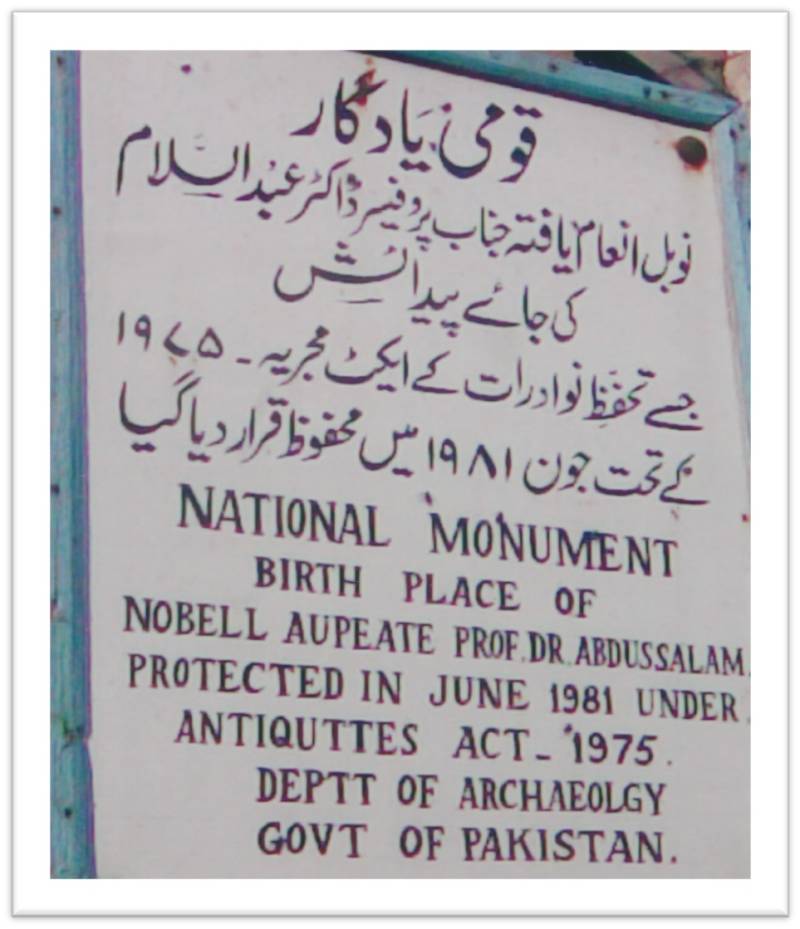

One wintry morning, in 2010, I travelled to Jhang, the birthplace of Dr Abdus Salam. A friend took me to the overcrowded inner city. The extremely narrow streets were hardly four-feet wide, with overflowing drains, innumerable flies, insects, and stench filling the air. When asked about the house of Dr Abdus Salam, a young man replied, “Salam – the butcher?” Another person took us to the owner of a cycle repair shop. The entry to the house was locked. A weatherbeaten wooden door led us into the house. A sign board, hand written both in Urdu and English, affixed on top, described it all!

As the door creaked open, we were welcomed by two bleating goats. The lawn was ill-kempt. This led us into two small dark rooms. One was empty and the other had a charpoy and some fodder for the animals. Upstairs, on the roof, one could see the densely populated inner city with adjoining houses. Live electric wires crossed each house, dangerously exposing the residents. The side walls had clothes spread out to dry.

Nearby, a small mosque and a shady banyan tree stood majestically. Both were visited by Salam as a child; the mosque for daily prayers and the banyan tree shade to ward off scorching heat while studying.

Upon seeing this dwelling, a ‘national monument’, I fell speechless. The pathetic state made me recoil. On seeing my tortured face, my guide asked fearfully, “What happened?”

I responded as if a ghost had appeared. My lips quivered and hands shook. I muttered a few words. Then, slowly, as my voice cleared, I said, “The Nobel Prize goes to those who have conferred greatest benefit to mankind. Is this how we honour the son of the soil?” Here, in his own homeland, it seems, he received the most grotesque eructation of prejudice and hate.

Paradoxically, the outside world treated him as a celebrity. Having received innumerable awards and honours, travelled over 30 countries and met many heads of states made him a roles model for young scientists the world over.

Dr NM Butt, Professor Emeritus and Chairman of the Pakistan Science Foundation told me in one of our meetings, “I was in Trieste when Dr Salam received the Nobel Prize. In his honour, the entire city was lit up at night to celebrate their prodigy. It was a spectacular event, most awe-inspiring!”

Trieste – an Italian city, remembered as ‘the Sleeping Beauty’ and ‘Shanghai of eastern Europe’ had seen times when the likes of Sigmund Freud and James Joyce strolled the streets. Triestini take pride in their sea, it is there and it will always be there. Similarly, the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) is there and it will always be there – a scientific accelerator to rejuvenate the ideas of Salam.

Professor (General) Muhammad Aslam, principal of two prestigious medical institutes of the country and eminent scholar, told me, “I was representing the National University of Sciences and Technology, Pakistan, to John’s Hopkins University, USA. A delegate walked up to me and asked, ‘Are you from Pakistan?’ I answered in the affirmative. To this, he responded spontaneously, ‘I know Pakistan through Dr Abdus Salam.’”

General Muhammad Safdar, Chief of the General Staff of the Pakistan Armed Forces, and later Vice Chancellor of Punjab University and Governor of Punjab, was ambassador-designate to Morocco. He told me: “Dr Abdus Salam was invited by the King of Morocco. He was on a wheelchair. The King walked up to Dr Salam and greeted him warmly. I, as an ambassador was most impressed.”

In the New Scientist weekly, 14 July 2012 issue, on page 5, a bearded, bespectacled Pakistani scientist is shown:

“Abdus Salam, giant among physicists.” It goes on to tell us as to“[…] How Pakistani physicist Abdus Salam, with Americans Steven Weinberg and Sheldon Glashow, developed the electroweak theory that unifies two of the four fundamental forces. Their work helped complete the standard model, of which Higgs is the final part to be observed, and won the trio the 1979 Nobel Prize for physics.”

It further adds, “Despite his success, Salam was forced to leave Pakistan in the 1970s […] ‘Among physicists both men (Dr Salam and Dr S Bose) were regarded as giants,’ says Jim Al-Khalili, a physicist at the University of Surrey, UK. ‘Science transcends such petty distinctions as race, nationality or religion. If only the wider world did too.’”

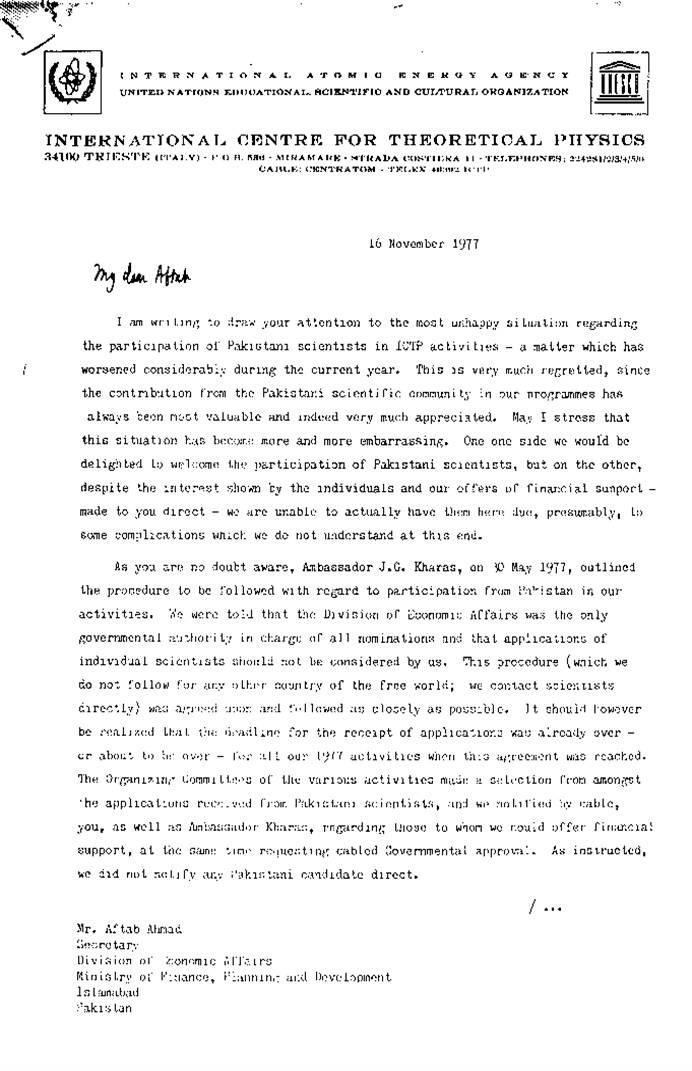

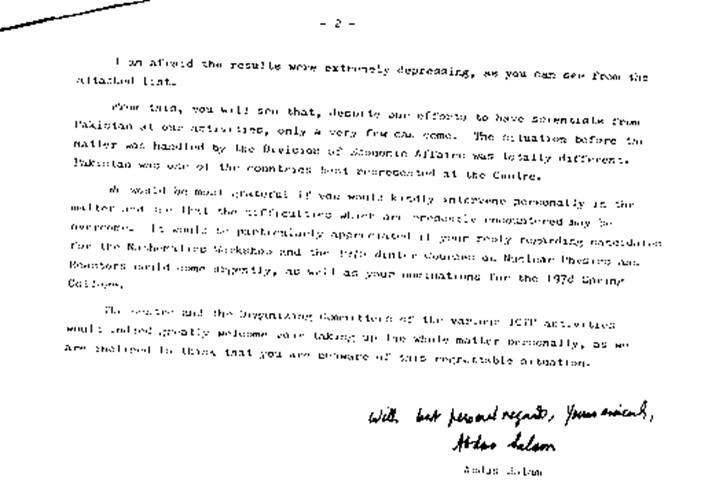

As a man of two worlds, he worked tirelessly to help ‘educate’ his fellow countrymen. In one of his letters he expressed his nagging anguish at the apathy of the bureaucracy. Writing from his “International Centre of Theoretical Physics, Trieste (Italy)” dated 16 November 1977 to Mr Aftab Ahmad, Secretary, Division of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Planning and Development, Islamabad Pakistan, he laments;

“My dear Aftab,

I am writing to draw your attention to the unhappy situation regarding the participation of the Pakistani scientists in ICTP activities – a matter which has worsened considerably during the current year. This is very much regretted, since the contribution from the Pakistan scientific community in our program has always been most valuable and indeed very much appreciated. May I stress that this situation has become more and more embarrassing. On one side we would be delighted to welcome the participation of Pakistani scientists, but on the other, despite the interest shown by the individuals and our efforts of financial support – made to you direct – we are unable actually to have them here due, presumably, to some complications which we do not understand at this end.”

A young brilliant clerk, who worked as my secretary, showed in excitement a personal letter written by Dr Abdus Salam: “I herewith provide you with scholarship to pursue your postgraduate studies.”

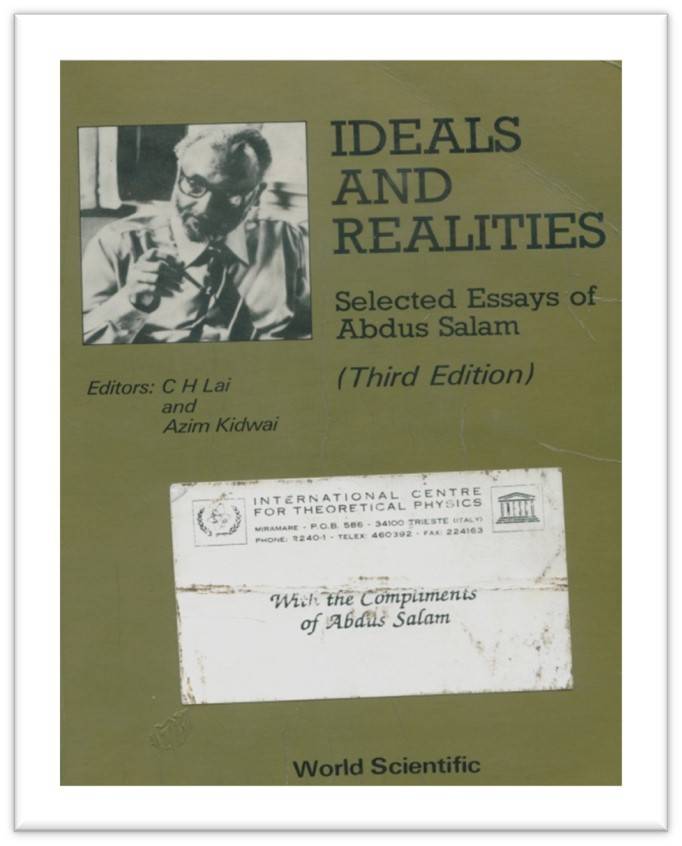

In 1987, I received a copy of Ideals and Realities, containing his compelling talks, with many anecdotes. I have treasured it since.

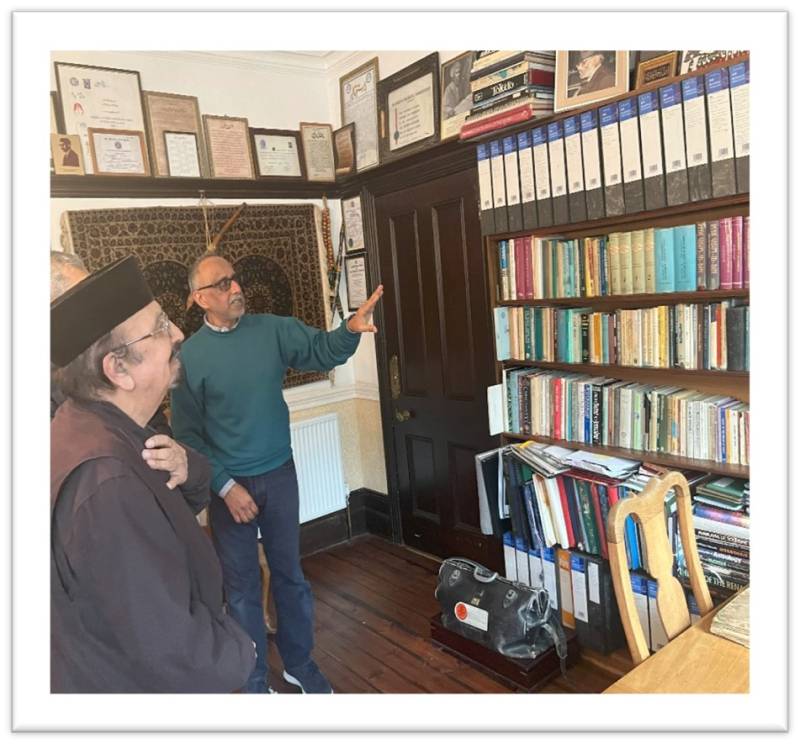

Recently, I visited Dr Abdus Salam’s house where British Heritage erected a blue plaque in 2020 at 8 Campion Road, Putney, SW15 6WW, London Borough of Wandsworth. Here he lived for almost 40 years, from 1957 till the end of his life in 1996.

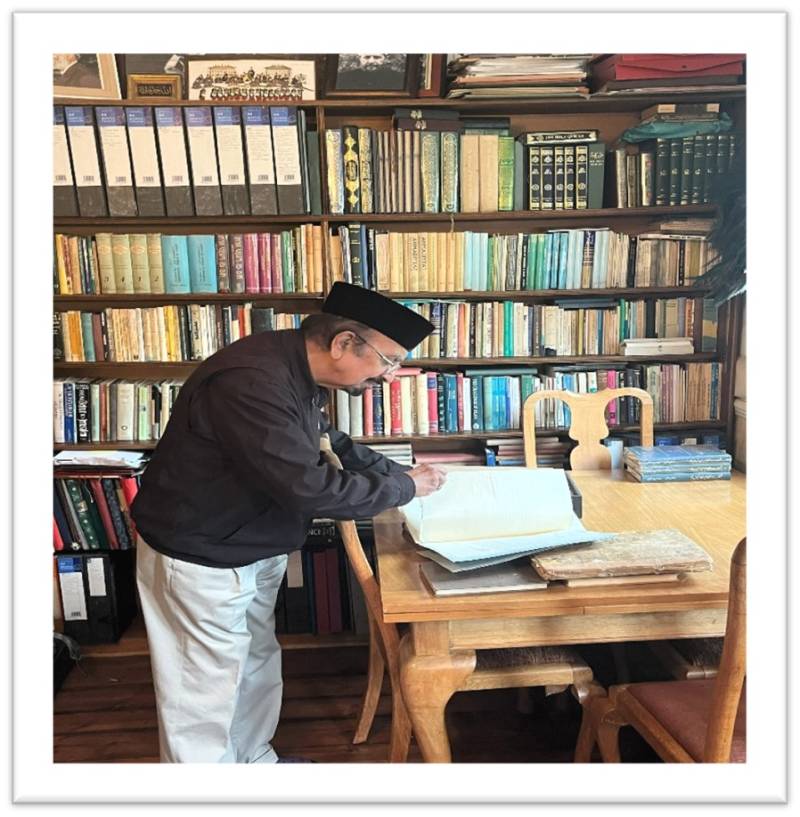

His son Ahmad Salam showed me his room where Abdus Salam worked, preserved much as he left it with his books: the Holy Quran, Hadith books, Persian literature, his favourite PG Wodehouse novels and even books on medicine.

I was also shown his record player, and the easy chair where he sat cross-legged in a woolly hat to think and write, while listening to long-playing records of Holy Quranic verses and an eclectic variety of music by composers as Strauss or Gilbert.

Dr Abdus Salam’s personal items including, diaries, notes and diplomas were arranged in his room.

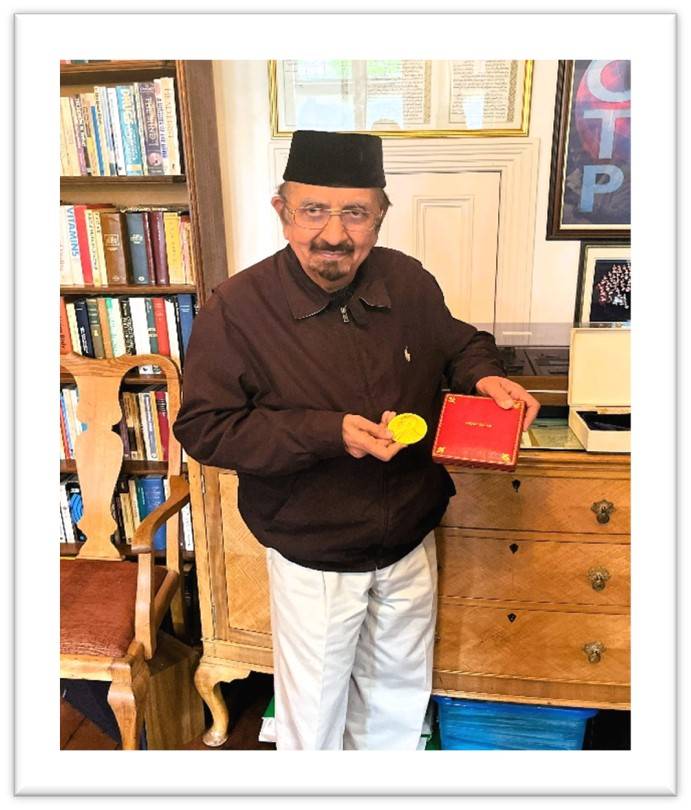

Ahmad Salam (his son) brought the Nobel Prize Medal from safe custody to show us. The medal has a portrait of Alfred Nobel in left profile on the obverse, and the years of his birth and death.

The medal is struck in 18-carat grain gold, plated with 24-carat gold, and weighs about 175 grams. The name of the recipient was engraved on the edges of the medal.

I had the unique privilege to visit Imperial College London and saw the Abdus Salam Library, which is in recognition of Dr Abdus Salam’s tremendous contribution to that college, as well as to the world of physics and science more generally.

“I hope the new Abdus Salam Library inspires many more people in years to come,” said Professor Hugh Brady, President of Imperial College.

Dr Abdus Salam, as I knew him, was a very passionate man. He was warm, friendly and open, with none of the aloofness usually associated with the great. He championed the cause of advancement of science among the marginalised. Despite repeated humiliation at the hands of his own country, he remained obdurately obedient to Allah. I echo the words of Gordon Fraser, physicist turned science writer, in his book Cosmic Anger:

“Once released from the cocoon of his modest beginning, his relentless drive, his ‘cosmic anger’, continued for the rest of his life, but frequently had to combat blindness, prejudice and disinterest. Here and there some seeds of this anger fell on fertile ground, and flourished. Salam left other seeds that have yet to germinate. As in the dry desert that blooms after a sudden rain following years of drought, perhaps these desiccated husks can still flower. As years pass, those who visit the institute in Trieste or learn of the science that bears Salam’s name will know less of him as a man, but his pioneer aspirations live on as his spirit is fervently passed from one generation to the next.”