“Great deeds are done when men and mountains meet; this is not done by jostling in the street”

(William Blake)

The 7th of July reminds us of the story of Lalak Jan, the quintessential soldier and a brave denizen of the mountains, whose rendezvous with martyrdom atop a mountain post proved the above dictum true. He belonged to an ancient Burushaski-speaking race inhabiting the ethereally beautiful Yasin valley whose martial élan is regarded with respect by various historians and sociologists.

Lalak Jan’s village Hundur lies nestled amongst the Hindukush mountains in the veritably golden valley of Yasin in the Ghizer district of Gilgit. The valley, which is famous for its hot springs in Darkut, rises up towards the Wakhan corridor through Darkut pass. Darkut is also famous for the murder of an Englishman John Hayward in 1870 at the hands of armed men in the pay of Mir Wali, the ruler of Yasin. The murder still evokes fear amongst the readers of history for the fiercely xenophobic spirit of the denizens of the valley.

The Yasin River, which drains the valley, gracefully meanders its may throughout the length of the valley before merging with Ghizer river. Lalak Jan’s village lies on the right bank of the river at an altitude of around 8,500 feet. The verdure of the village is contrasted beautifully by the jagged serenity of the brown and grey mountains overlooking it on both sides, where nature’s colours lie scattered as if on a master painter’s canvas. It is an ideal locale for a free-spirited and intrepid folk whose courage is only equalled by their industry – evidenced in the shape of a profusion of terraced fields of golden tasselled corn and thickets of fruit trees like walnut, apricot, mulberry, apples and cherries. The village is as much an idyllic abode for the romantically inclined as an eyrie of the ruddy coloured Burushaski-speaking folk.

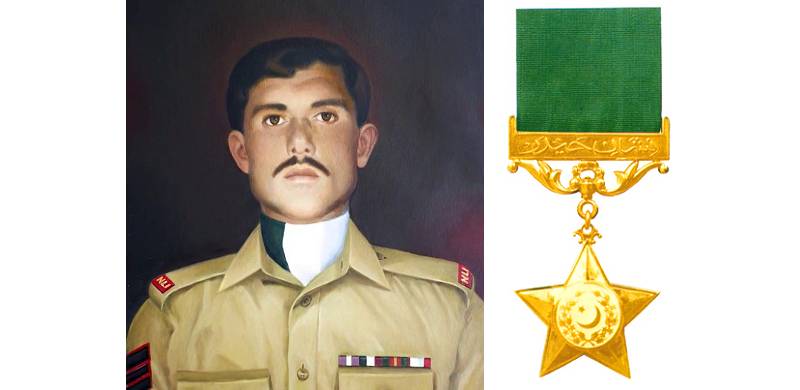

Bathed in such heavenly beauty now lies the grave of the Havildar Major Lalak Jan, Nishan-e-Haider, the recipient of the highest gallantry award of the country. The grave, an unpretentious little masonry structure, is covered with a plethora of multihued flowers of the valley, swaying in the gentle breeze. Atop the grave flies the flag of Pakistan, proudly fluttering most of the time due to the irrepressible breeze of Yasin – much like the intrepid spirit of its inhabitants.

At a distance of around twenty yards from the grave of Lalak Jan is the grave of another martyr, his cousin Ibrahim who embraced martyrdom in the same conflict in an adjacent sector five weeks prior to Lalak Jan’s supreme sacrifice. It is on Ibrahim’s death that Lalak Jan had uttered his wistful remark that “Alas! Ibrahim has overtaken me in life.” The two cousins had a healthy rivalry and respect for each other since childhood. Now both lie buried side by side suffused in the glory of martyrdom, two unforgettable parts of the local martial folklore reminding one of the soul stirring verses of an English poet: “Here lies the noble gladiator; his manly brow consents to death but conquers agony.” Neither a requiem nor a blind deification can do justice to the lofty deed that was done on the comparable heights.

A trip to the multihued paradise called Yasin valley is a visual delight. The village Handur lies at about six hours’ journey from Gilgit. The jagged serenity of the towering mountains is offset by the sylvan beauty of the valley dominated by the russet stalks of ripened wheat and green terraces of fully gown corn. It is a landscape dappled by crimson hues of pomegranate buds, green walnut trees, rubicund apricot laden branches and greenish yellow apples waiting to be plucked. A narrow dirt track which gets further narrow upon entering village Handur leads to the home of Lalak Jan shaheed. A modest stone walled house with few rooms is where Lalak Jan lived. One of his cousins points proudly to a wall in front of a small living room constructed by Lalak Jan during one of his vacations.

The questions in the mind of this scribe were about whether Lalak Jan was an ordinary soul stirred into momentary action or preprogrammed by the nature to meet the hallowed end he met. Was he taciturn or garrulous, quarrelsome or complaisant? Was he possessed of a phlegmatic temperament or a sanguine spirit? A three-hour-long discussion with his father, a gaunt Burushaski speaking man with nondescript features, and a few close relatives, painted a very interesting picture of the man.

He was no ordinary man indeed – and his personality had so many angles and contrasts that it made him an enigma. This scribe was instantly reminded of a description of Douglas Mac Arthur by William Manchester, in a well written biography American Caesar: “He was a thundering Paradox of a man with protean tastes.” The description fitted the personality of Lalak Jan very well indeed.

Lalak Jan was born at Morang, a sleepy little mountain hamlet located short of Darkut. His birth was heralded by a massive avalanche accompanied by a thunderstorm still remembered with awe by the village folk. Perhaps it was the harbinger of the stormy soul of Lalak Jan, who, in memory of that storm, added “Dohat” in front of his name (Dohat in Burushaski means storm). Lalak Jan was a free-spirited, bold and irrepressible lad in his childhood.

Due to the straitened economic circumstances of his family, he could not be sent to school like other children. He loved climbing mountains and was a most expert cragsman who climbed precipitous slopes with ease. He used to squelch his way up the snow-covered slopes and come glissading down the glaciers without any fear in his heart.

The exploration of moraines and glaciated heights was his hobby as he relished cattle herding on slopes and heights hitherto thought unclimbable by people. Village folks remember nostalgically the rubicund face of a twelve-year-old lad returning amidst the penumbra of creeping mountain shadows after a successful mission of cattle searching; his face festooned with icicles and knuckles bruised because of frenetic climbing. Many a times he retrieved cattle from ravines and crevasses considered impenetrable by people.

Unique man that he was, he retained his joi de vivre till the end. He used to shout in jest at the Indians while lobbing occasional stones at enemy troops

He possessed a rare thirst for education right from his childhood. Along with a cousin of his who bore testimony to the event, one day he went to the local primary school out of pure curiosity. They were invited for a seat by the teacher who instantly took a liking to the lad. Thus began the first brush with formal education of a free-spirited highlander. His churlish demeanour and rustic independence were mellowed through the academic regimen. In school his teacher remembers him to be a chief prankster who loved to be in the eye of every storm. He was not a very hardworking or plodding type but very quick on the uptake.

An event remembered by his relatives throws light on his physical tenacity. As a thirteen-year-old, while he was collecting firewood one stormy winter afternoon, a big bough from a willow tree fell on his head. He sustained a serious head injury and remained unconscious for 18 days in hospital. His subsequent recovery was described as a miracle by the doctors. His cousins recount with fondness that the injury had further heightened his aggressive nature. As a child he loved playing cricket and was a good batsman by village standards. He however disliked getting out while batting, which in his opinion was akin to capitulation, a concept he abhorred since childhood.

He was growing into a true iconoclast who used to chide superstitious beliefs of locals, such as the avoidance of traveling on Sundays. He nursed anger at social inequities and longed to get himself and his people out of a state of penury and ignorance. The story of his joining the army is also indicative of an independent streak in his personality. His father sent him on an errand to Taoos, a nearby town. He, instead of returning home, made his way to Gilgit, where he presented himself before a recruitment committee and got enlisted in the Northern Light Infantry (NLI). This was typical of a 16-year-old headstrong lad who loved taking independent decisions.

Lalak Jan, according to his close friend and cousin Zorawar Khan, was an extremely sensitive soul who masked his sensitivity behind a stern exterior. He nursed a pathological antipathy for inequality of any kind and openly spoke disparagingly of those public representatives of his area whose hypocrisy lay masked in their Good Samaritan pretensions. He was a keen participant in village social life and community development. Always a generous contributor to philanthropist causes, he once openly berated a local councillor for his profligacy with public donations when he was trying to garner financial support for a project. His cousins still recall with glee the discomfiture of the corrupt councillor whom he accosted in his typically blunt style and stentorian voice, “I swear upon my honour that I will contribute ten times more than all of you combined provided you prove that you spent each and every penny of the last donations on some worthwhile project.”

This scribe was amazed to discover that Lalak Jan had founded an NGO named Al Madad Welfare Organisation with a set of objectives to uplift the general state of education and civic sense in the region. He used to contribute a sum of rupees five hundred every month for the NGO out of his modest pay. This was indeed a remarkable display of altruism and sagacity while serving in the army, whose worldview is supposed to be proscribed by the perfunctory humdrum of a tough routine.

The more one delved into the details about his life the more one found out that there was nothing prosaic about the man.

His uncle played a cassette which contained a recording of Quranic verses in the contralto voice of Lalak Jan; it was a most soulful rendition of verses His virtuoso rendition of Quranic verses was as good as his facility with the Rubab, the traditional music instrument of the Yasin Valley. The catholicity of his interests reveals a sensitive soul in an iron heart longing to express itself in myriad ways.

Lalak Jan was inducted as a recruit in the NLI troops on 18 December 1984. After joining 12 NLI Regiment, he worked very hard to get himself trained as an accomplished soldier and was promoted to the rank of Havildar in 1993.

He distinguished himself in his early military career by doing his courses in top grade. He mostly held appointments of eminence at the regimental level and was serving as Company Havildar Major of his company in the Northern Light Infantry regiment when skirmishes broke out on the Line of Control. Lalak Jan was amongst the first six soldiers who were sent on reconnaissance in December 1998. He was on an extended leave in his hometown when the news of his battalion’s involvement in armed clashes along the Line of Control reached him. He rushed back at once without receiving any call notice, forsaking six days of his hard-earned leave.

The difficult nature of the area where his unit was deployed in defence of the motherland can hardly be imagined unless seen. Characterised by towering peaks, deep ravines and narrow gullies, it was a place where nature tested the limits of human endurance. Travelling in the northern areas, a British scholar John Keay had written about the area, “There is something not just ridiculous but profane about organised warmongering in such wild and mighty surroundings.”

Company Havildar Major Lalak Jan soon after arrival in the war zone volunteered for the hottest sector in the battalion’s area of responsibility and was transferred to a difficult location at Qadir Post on 5 July 1999. The adventurer in him found his vocation at last, when he was at the most threatened post of the battalion, where the enemy had started launching attack after attack with a battalion strength.

His finest hour came on 7 July when he was manning a screen post ahead of his main post. It was virtually a David versus Goliath match with Lalak Jan’s post of 22 men pitted against a complete battalion of the enemy. He encouraged his men with his raw courage and conducted an aggressive defence with textbook dexterity. His daring attack ahead of the main defensive positions against an enemy patrolling party resulted in heavy loses to the enemy in terms of men and weapons. His post being the most dangerously exposed amongst the entire defences, it bore the maximum brunt of the enemy’s frenzied attacks. After several days of continuous fighting, he was given an option for relief – which he declined to accept. The enemy artillery had temporarily blocked all logistical sustenance and the men under their intrepid leader held waves upon wave of company-level attacks at bay.

The enemy artillery, air and direct firing weapons were targeting this post and pulverising the jagged rocks. There was the smell of cordite everywhere, turning even the water deposits in rocky crannies into poison.

Eventually, the fusillade of enemy direct firing weapons started taking its toll as the 22 men started becoming targets of its fury. They had managed to repulse seven main enemy attacks in the last 48 hours. The indomitable Lalak Jan kept moving from trench to trench, egging his wounded colleagues to fight on. Indian fury knew no bounds as they found this small post resisting their implacable pressure with dedication.

After ten continuous days of relentless combat, most of the troops had fallen in the line of duty, while others lay seriously wounded. Now Lalak Jan was the sole able-bodied member of the post along with two semi-mobile but injured colleagues i.e Sepoy Bakhmal and Lance Naik Bashir.

The post was temporarily cut off from the rear and a relief operation was underway. Undeterred, Lalak Jan kept the enemy at bay by flitting from one fire position to another and firing in all directions. The confused enemy troops, now almost within hearing distance, were misled into believing that the defenders were resorting to some sort of a ruse. There was an eerie silence on the Pakistani post, broken only when Lalak Jan picked up the weapon of his martyred colleagues to fire. He now had an option to fall back, but chose not to – instead reassuring the relief force that he will hold on till their arrival.

Unique man that he was, he retained his joi de vivre till the end. He used to shout in jest at the Indians while lobbing occasional stones at enemy troops, remarking that “I am sending you the gift of a Chinese grenade, please acknowledge.” He appeared to be a live apparition amongst the dead and wounded, personifying the hero extolled by Dryden in his memorable verse, “And Wars have that respect for his repose, as winds for halcyon when they breed at sea.”

Lalak Jan held on tenaciously to the third trench on his post while the first two were being run over by the leading elements of attacking enemy troops. In this final struggle, he received bullets in his chest while trying to lob a grenade towards the enemy intruders. He was joined by two soldiers from his unit’s base camp i.e Sepoy Iftikhar Hussain and Shaheen. They found that Lalak Jan was hit by three bullets, two in the chest and one in the leg. He sent the two soldiers back to a safe position saying, “I will keep enemy at bay, you go back and join the main counter-attack force.”

Salutes to this brave son of Hundur, who still held on for another four hours of epic struggle. These four hours found his life ebbing away, yet he kept on firing at the enemy. His last stand allowed the relief force to trudge up the serrated crest line to effect a link-up with the post. The enemy was beaten back and the post that Lalak Jan defended is still a part of Pakistan.

Thus died the phenomenon called Lalak Jan, the way he lived: joyously, proudly and fighting against injustice.

The country conferred the highest gallantry award, the Nishan-e-Haider on him. He was indeed a quintessential soldier, hearty, sporty and sanguine; his ebullience balanced beautifully by a sensitivity of soul and solicitude for the dispossessed. His abiding legacy is not only the flame of courage lit in the hearts of young men of Yasin, but also a yearning for knowledge embodied in the form of a school under the aegis of Al Madad Welfare Trust founded by him.

The legend of Lalak Jan lives on the icy peaks of Kargil as well as the ethereally beautiful village of Hundur in Yasin Valley, reminding people of a warrior who lived and died as a hero.