“The pain runs deep in my veins, deeper than the cuts from the bricks I haul day in and day out. Despite my toil, the brick kiln owner sees fit to degrade me with the term ‘choora’ (sweeper), a reminder of my lowly status,” Daim lamented. “Once my family was briefly freed from the shackles of agricultural bondage, I harboured aspirations of attending school. Three years have passed since then, and my dreams of education have withered away like the dust on these sun-scorched bricks.”

The tale of Daim’s family's bondage bears witness to the sweat and tears shed under the weight of three distinct forms of bonded labour, each tightening its grip around their collective dreams and aspirations. Daim’s father, a weary agricultural labourer, took a loan of PKR 20,000 from a brick kiln owner to pay a debt to his landlord, a desperate bid to liberate the family from the clutches of poverty. Little did he know that he was merely exchanging one form of bondage for another. The family's hardships stretched far beyond the kiln. Over the course of a year, Daim’s father realised that his income was insufficient and he resorted to taking out more and more loans just to put two meals on the table for his family.

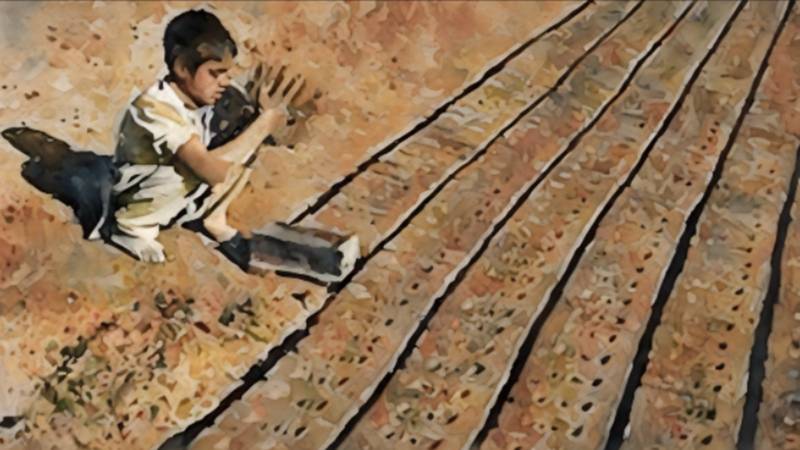

Eventually, the owner of the brick kiln coerced the entire family into servitude to repay the debt. Now, Daim’s mother and his 12-year-old sister are compelled into domestic bonded labour within the owner’s residence, enduring gruelling 12-hour workdays. Daim’s two younger sisters, ages 8 and 6, spend the entire day alone in a muddy room provided by the brick kiln owner, awaiting their mother's return to receive their meals and comfort. Amid the stifling heat of the kiln, Daim takes on the responsibility of preparing meals for himself and his father, all while labouring to make bricks, exposed to hazardous conditions. Meanwhile, his older brother remains entrenched as a bonded labourer in agriculture.

The family, once united, is now scattered across three forms of bondage, each exacting its toll on their bodies and souls. Despite their relentless efforts, debts continued to accumulate, reaching a staggering PKR 400,000 within four years. Their dream of education and freedom faded into obscurity. To the world, they are mere commodities, traded by those wielding power. But in Daim’s heart, the anguish of a child trapped in bonded labour echoes louder than any insult he endures, a poignant reminder of the injustices staining this world.

This narrative exposes numerous violations of children's rights, including child labour, lack of education, forced labour, family separation, and poverty, particularly prevalent in marginalised communities. It challenges the outdated view of children as passive recipients, advocating for a child-centered approach that empowers them to take on leadership roles in advocating for their rights. Children like Daim, despite being trapped in bonded labour, can emerge as leaders. Daim’s resilience, shown by enduring harsh conditions while caring for his family, demonstrates the inner strength essential for leadership. His aspiration for education, despite significant obstacles, reflects his forward-thinking mindset and vision for a better future. Additionally, his empathy and responsibility, evident in his care for his family and work alongside his father, highlight his commitment to addressing community needs. To nurture Daim’s tremendous leadership potential, a child-centered approach is necessary. Although children may not hold formal positions, they inherently possess essential leadership qualities such as creativity, curiosity, and resilience. Ronald Heifetz, a Harvard professor and iconic author on leadership, refers to this concept as "leadership without authority."

Bonded labour is prevalent in Pakistan, ranking 19th globally and 4th in Asia-Pacific, with an estimated 3.1 million labourers mainly in agriculture, brick kilns, carpet weaving, and mining. Brick kiln bonded labour is one of the most pervasive forms in Pakistan, the third-largest brick producer in Asia with an estimated 45 billion bricks annually. According to a study by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), around 4.2 million children in Pakistan are engaged in child labour, many of them in brick kilns. These children work 16-hour workdays for meagre wages and are exposed to hazardous conditions, including extreme temperatures, airborne dust, and toxic fumes.

The 1973 Constitution of Pakistan includes provisions safeguarding the rights and welfare of children. Article 11(3) specifically addresses the prevention of hazardous child labour. Article 25A ensures access to free and mandatory education for children aged 5 to 16. Additionally, Article 25(3) advocates for the enactment of specialised legislation for the protection of children. Furthermore, Article 37(e) mandates the state to shield children from engaging in occupations that are inappropriate for their age and ethical development. Despite legislative efforts like the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act 1992, enforcement is weak as highlighted by the National Commission of Human Rights Pakistan. This makes bonded labourers more vulnerable because they have little to no voice in speaking for the enforcement of the laws.

The involvement of children from marginalised backgrounds in advocacy organisations and their engagement with policymakers can expedite policy changes

The multi-faceted issue of child bonded labour can be examined through Heifetz's adaptive leadership framework, which focuses on tackling complex challenges that necessitate shifts in people's values, attitudes, and behaviours. The six principles of Heifetz's adaptive leadership framework—such as 'getting on the balcony,' identifying adaptive challenges, and regulating distress—can be directly applied to the issue of bonded labour. Technical challenges, like legal reforms and financial assistance, require authority-driven solutions. In contrast, adaptive challenges involve deeper systemic issues such as poverty, social hierarchy, and cultural discrimination. To effectively address both technical and adaptive challenges for transforming a child from bonded labour to a leader, it is essential to embrace a child-centered approach and implement a comprehensive framework composed of four essential pillars to foster the development of leadership skills in children.

Personal development (self-centred)

Implement programs that empower children by focusing on self-improvement. Through these initiatives, children who have been subjected to bonded labour can address their trauma, conquer their fears, and develop essential leadership skills. Children ensnared in bonded labour also need crucial assistance: necessities like food and shelter, medical attention, and legal support after setting them free. This holistic approach not only nurtures leadership qualities in children but also offers immediate relief to families in distress.

Economic Development (child- and mother-focused)

Create microfinance projects and vocational training schemes tailored for illiterate mothers, offering new income opportunities to families in bonded labour. By supporting the mothers' earnings, not only can children trapped in labour attend school, but they can also develop valuable life skills and business acumen by assisting their mothers in managing finances for small business endeavours. Investing in the education of bonded child labourers equips them with the tools to advocate for change and the knowledge and skills necessary to drive societal transformation, fostering a future where exploitation is no longer tolerated. Deputy Speaker Anthony Naveed of the Sindh Assembly passionately underscores that, “Empowering labourer children through education breaks the cycle of exploitation and bondage. By investing in microfinance projects and vocational training for illiterate mothers, we create avenues for economic independence, enabling children to attend school and acquire essential life skills. This investment not only transforms individual lives but also lays the foundation for a society where exploitation is replaced with empowerment and opportunity."

Social Development (children- and senior–citizens focused)

Establish initiatives aimed at educating both bonded child labourers and adults about their rights by fostering intergenerational connections. By bringing together children and senior citizens, we bridge gaps in knowledge and experience, creating opportunities for mutual learning and growth. These initiatives will foster community support networks aimed at assisting families in vulnerable situations. Within these networks, both children and senior citizens will play equally important roles in supporting each other. Children will take on dual responsibilities as both beneficiaries and leaders, actively engaging by offering peer support and advocating for their communities. Simultaneously, senior citizens will serve as mentors, providing guidance, emotional support, practical assistance, and opportunities for personal development. This collaborative approach ensures a nurturing environment where every generation contributes to the collective well-being with mutual support and encouragement.

Political development (children- and policymakers-focused)

Create avenues for bonded labour children to share their stories and insights with policymakers, an essential step in addressing technical challenges like legal reforms. By amplifying their voices, society can acknowledge children’s leadership potential and strengthen their efforts to combat bonded labour and other injustices. The involvement of children from marginalised backgrounds in advocacy organisations and their engagement with policymakers can expedite policy changes. A notable example can be seen in Pakistan, where parliamentarians such as Mehnaz Akbar Aziz, former Chairperson of the Parliamentary Caucus on Child Rights, former Senator Kamran Michael and Naveed Aamir Jeeva, former Parliamentary Secretary Ministry of Poverty Alleviation and Social Safety facilitated meetings between minority children and top government officials. These children demonstrated their leadership by presenting a charter of demands to key governmental figures, including the Chairman of the Senate of Pakistan, the Speaker of the National Assembly of Pakistan, and the Governor of Punjab. Among their demands was the urgency of increasing the marriage age for Christian boys from 16 to 18 years and for Christian girls from 13 to 18 years. As a result, former Senator Kamran Michael's efforts bore fruit as the bill passed through the Senate successfully. It indicates that children, with their unwavering honesty and unyielding spirit, are the most powerful advocates of their rights.

Conclusion

Through initiatives focused on personal, economic, social, and political development, we can empower children like Daim to reclaim their agency, their voices, and their futures. By investing in their education, nurturing their talents, and amplifying their voices in the corridors of power, we can create a world where every child is free to dream, to learn, and to thrive.

Daim's story is not merely a tale of suffering; it is a call to action—a call to stand in solidarity with the most vulnerable among us and to strive for a future where no child is shackled by the chains of bondage. It is a reminder that the true measure of our humanity lies not in our ability to turn a blind eye to injustice but in our willingness to confront it, to challenge it, and to build a world where every child can soar unfettered by the weight of oppression.