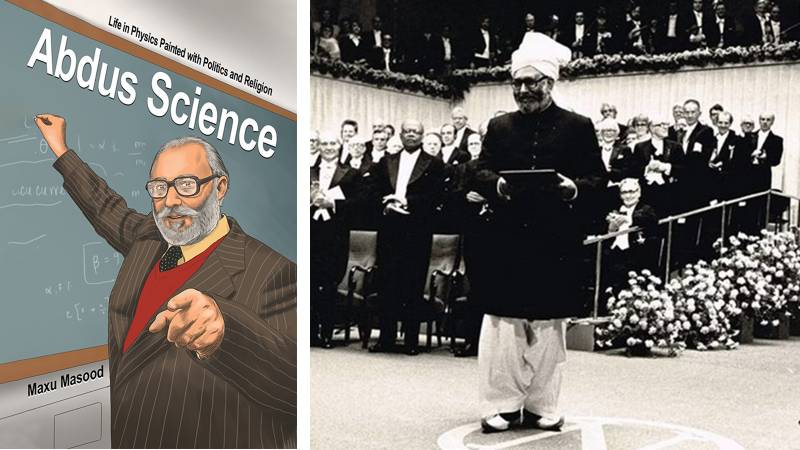

Abdus Science is a discrete biography of Abdus Salam (1926-1996), the British-Pakistani scientist who shared the 1979 Physics Nobel Prize with Sheldon Glashow (b 1932) and Steven Weinberg (1933-2021). Rather accurately, the prize was awarded in Theoretical Physics, the Rolls Royce of sciences, in recognition of scholarly struggle focused upon evolving a unified grasp of natural phenomena. Indeed the contribution made by three scientists secured them an intellectual lineage next to Isaac Newton (1643-1727), James Maxwell (1831-1879) and Albert Einstein (1879-1955).

Unlike the mainstream of great scientists – educated in Europe and the United States, and sharing among themselves the Jewish-Christian intellectual tradition – Abdus Salam hailed from the humble household of a junior public servant in the vastly illiterate sun burnt outback of Punjab. Born in the vanishing hours of British colonial rule over India, he made it to the forefront of Theoretical Physics by his 25th birthday, winning the Chair of Mathematics in London’s Imperial College at 30. Much has been written about him, especially after the Nobel Prize, mostly in praise and admiration. Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) had once cautioned that flattery of great scientists equalled insult but her opinion seems to have been overlooked in view of the exotic hallow surrounding Abdus Salam.

On good judgment, Abdus Science embarks upon a picturesque departure from the classic agenda of idolisation. The book offers a fascinating tale of times, places and people enriching the life of Abdus Salam; a voyage across his personal life, and his religious and political inclinations over and above his main occupation with physics. Outside his working life, apportioned between London's Imperial College and the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, Italy, he served various military regimes and was closely associated with the birth of nuclear expertise in Pakistan. His devout membership of the Ahmadiyya schism marginalized him among Muslims. His fans perceive him as a victim of religious bigotry but, on his part, he did not seem to exercise scientific detachment in the world of religious belief.

Abdus Salam had two wives. His second wife, Louise Johnson (1940-2012), was a leading Molecular Biologist who served as Professor Emeritus in Oxford University; and it remains an awkward question as to how the two managed bigamy in Europe. Aside from his devout commitment to his religious community, Abdus Salam validated the Judaic-Muslim prohibition of pig meat and went as far as judging people who consumed pork as 'shameless' like the beast itself. Interestingly, he suspected that drinking buffalo milk led to mental obstinacy!

Abdus Salam had been a Science Advisor to the Government of Pakistan for over 15 years, lamenting that bureaucrats disabled his advice. He did not care to quit when Pakistan fought and lost expensive wars with India, when the poverty-stricken country planned to go nuclear, or when merciless military operations killing thousands of unarmed civilians were carried out in Balochistan and East Pakistan. In September 1974, however, he snapped the connection – protesting against the excommunication of his sect. He made Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, the Prime Minister of Pakistan from 1973-1977, a rather outlandish offer to return home and serve as a full-time member of the team of scientists making the nuclear bomb, in return for ditching the state-led excommunication of the Ahmadiyya. On a state visit to Pakistan in 1979, Abdus Salam pleaded for the same with Zia-ul-Haq!

Very often, Abdus Salam is credited with the establishment of the International Centre for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, Italy. Nevertheless, the centre was not a mere personal achievement, it was a collective diplomatic victory of members advocating the cause at the International Atomic Energy Agency. He did not credit Ishrat Usmani, the former Chairman of Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC), who had resolutely warned him to steer clear of housing the centre in a culturally insulated Pakistan.

Zafarullah Khan, a prominent member of the Ahmadiyya sect who served high-profile public offices in colonial India, Pakistan, the United Nations and the International Court of Justice (ICJ), remained a lifelong mentor of Abdus Salam. This relationship overlooked the fact that Zafarullah Khan championed religious bigotry publicly.

By itself, Abdus Science weighs up the scientist on a secular scale, exploring an assortment of nooks and crannies of his life hidden beneath the fog of fiction and folklore. A substantial amount of information provided in the book is supported by direct one-to-one interviews that the author of the book conducted with Abdus Salam at his London residence. Likewise, a considerable amount of rare records have been drawn upon for the first time. During interview sessions, Abdus Salam was sociable and polite – so long as discussion revolved round his own preferences for publicity.

At the end of the day, it is the candid approach of Abdus Science that calls for reading the book. It must be remembered that Abdus Salam was a scientist, not a priest; and the detachment of scientific methodology from personal life remains central to any down-to-earth portrayal of his life.