'Death and taxes’ is a famous quote that describes these two inescapable realities of life. People are familiar with the latter one. But the former tends to reverberate closer to home when one experiences it firsthand. Within a span of two weeks, I had the opportunity of not only observing death at close quarters, but also some astonishing phenomenon. My father remained hospitalized for a few days until he breathed his last. As an economist with interests in more than just bookish concepts, though, it was difficult for me to escape the reality that two parallel worlds were operating side-by-side, challenging conventional wisdom held dear by many in the economic realm.

This article is a humble attempt to bring to fore some interesting observations that would illuminate how ill-health propels economic activity. The observations do not follow any set pattern but are rather stated randomly.

The first thing that struck me was the role of higher prices. Prices, at least in the neoclassical synthesis, are central determinants of where resources should flow. In other words, they act as signals to investors. But prices have another very important function that tends to slip under the radar: higher prices tend to regulate congestion. Put another way, higher prices deter overcrowding. Besides private hospitals of repute, the working of this principle can be seen in full force at expensive dining places. While it is fashionable to lament city’s bourgeoisie thronging such places as their desire to reflect their status, the reality is that it is not just about buying power, but also about peace of mind and a bit of calm (compare it to a place where prices are low).

My father was admitted to a private hospital which has a considerable charge per day. But if you compare to the conditions to a subsidized government hospital, the inhuman treatment received, overflowing with people, and the quality of care, then it is worth it for those who can afford it. Despite the fact that a doctors’ strike was going on across the Punjab and there was a dengue outbreak, the hospital was still relatively uncongested. This owed primarily to higher prices.

Before I submit my second observation, it would benefit to recall what Adam Smith, widely regarded as the father of modern economics, prophesied about self-interest leading to socially desirable outcomes. Although yours truly has stated his observation a few times, it is worthwhile to state that Smith gave the example of a butcher selling meat not out of benevolence, but out of self-interest. But his self-interest indirectly served society’s needs. I experienced something very similar. My father remained in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) till his death. Outside the ICU were guards who made sure that only one or a few people are allowed to visit the patient. Every one of them carried a card that had the number of a particular ambulance service on it, requesting them to mention his name in case the call was made.

It is quite clear that they were guided by self-interest since every customer for the ambulance meant a certain percentage of profit earned going to their pockets. But their self-interest, as Smith astutely observed, facilitated a much needed service.

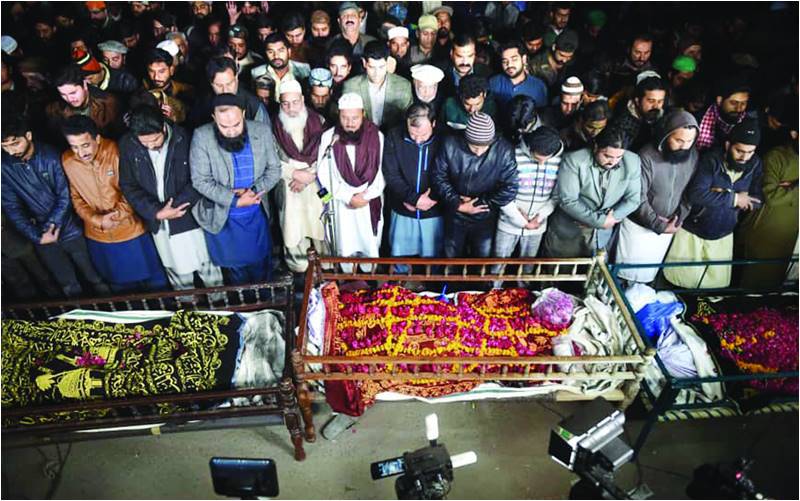

Yet, parallel to this self-interest driven activity, there existed another world driven by an opposite ambition. It was terribly hard to realize that our father had little chance of survival. Outside the ICU, as the family bonded together in grief, other aggrieved people took notice. We were continuously consoled by strangers whom we had never met, all of them offering their moral and financial support. Many women sat with my sisters and mother, offering Quranic verses and prayers for the well-being of my father. On one of my night stays, a stranger brought me dinner and tea. Many others met me and offered their unconditional help whenever required.

This was a world of ‘selfless interest,’ if one may call it like that. Never was there an occasion where anybody could doubt the benevolence of the strangers and their good, selfless intentions. It is hard to explain this behavior through any model. Perhaps death, illness and injury have the power to subdue our selfish nature and bring out the best within us. While self-interest has the power to pit us against each other, selflessness acts as a gravitational force by binding human souls together.

Finally, another interesting observation came at the time of burial. It was my father’s wish to be buried in Islamabad. But as its denizens would testify, it is a prohibitively expensive place where owning a piece of land can be quite a challenge. The same challenge confronts those who wish to bury their loved ones here. As we were grappling with the challenge, a particular law enacted by the Capital Development Authority (CDA) came to our rescue. As per this rule, an owner of a plot in Islamabad is entitled to two graves. Readers may not appreciate the fact how helpful this was in easing the formidable challenge of finding a grave in the capital.

But also notice the clever ploy by the CDA. Knowing well that supply of burial land, at least in the cities, is way shorter than the demand, it incentivized investment in Islamabad through offering graves as complementary good with the investment in land. And investment in land is the lifeline of CDA since it is the biggest source of revenue for the cash-strapped organization. So here again we observe Smith’s classic maxim of self-interest leading to provision of a much needed good. It is not out of benevolence or God’s fear that CDA attached graves as a complement to investing in Islamabad, but rather out of self-interest (the bigger the quantum of such investment, larger the probability to extract a rent under the table). Yet this self-interest, indirectly, provides a needed service.

It is to be noted here that burials are still not free. One still has to pay for the services of preparing a grave and other complementarities, which reflects additional taxes This is a slap on the face of our brain-dead ‘leaders’, who one after the other have made it a habit to call out Pakistanis as tax thieves. Many writers, including yours truly, have been trying to dispel this notion by insisting that we are taxed from birth to death. Is the payment made for graves not a tax?

One gets to witness other interesting phenomenon. For example, the hotels near the hospitals that provide 24-hour service, and tea stalls within the hospital building that sell goods at higher rates than in the market (there are no competitors, at least within the hospital space, and consumers willingly pay to avoid the physical and mental effort of going out). But the above stated should suffice to drive home my assertion about economic activity spinning around death and health misfortune.

I will conclude by suggesting that experiences like illness, disability and death have the ability to bring forth interesting observations regarding human behavior. Our family went through a traumatic experience. But as that experience unfolded, the reality that the world is not so simple was laid amply bare.

The writer is an economist

This article is a humble attempt to bring to fore some interesting observations that would illuminate how ill-health propels economic activity. The observations do not follow any set pattern but are rather stated randomly.

The first thing that struck me was the role of higher prices. Prices, at least in the neoclassical synthesis, are central determinants of where resources should flow. In other words, they act as signals to investors. But prices have another very important function that tends to slip under the radar: higher prices tend to regulate congestion. Put another way, higher prices deter overcrowding. Besides private hospitals of repute, the working of this principle can be seen in full force at expensive dining places. While it is fashionable to lament city’s bourgeoisie thronging such places as their desire to reflect their status, the reality is that it is not just about buying power, but also about peace of mind and a bit of calm (compare it to a place where prices are low).

According to CDA regulations, an owner of a plot in Islamabad is entitled to two graves

My father was admitted to a private hospital which has a considerable charge per day. But if you compare to the conditions to a subsidized government hospital, the inhuman treatment received, overflowing with people, and the quality of care, then it is worth it for those who can afford it. Despite the fact that a doctors’ strike was going on across the Punjab and there was a dengue outbreak, the hospital was still relatively uncongested. This owed primarily to higher prices.

Before I submit my second observation, it would benefit to recall what Adam Smith, widely regarded as the father of modern economics, prophesied about self-interest leading to socially desirable outcomes. Although yours truly has stated his observation a few times, it is worthwhile to state that Smith gave the example of a butcher selling meat not out of benevolence, but out of self-interest. But his self-interest indirectly served society’s needs. I experienced something very similar. My father remained in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) till his death. Outside the ICU were guards who made sure that only one or a few people are allowed to visit the patient. Every one of them carried a card that had the number of a particular ambulance service on it, requesting them to mention his name in case the call was made.

It is quite clear that they were guided by self-interest since every customer for the ambulance meant a certain percentage of profit earned going to their pockets. But their self-interest, as Smith astutely observed, facilitated a much needed service.

Yet, parallel to this self-interest driven activity, there existed another world driven by an opposite ambition. It was terribly hard to realize that our father had little chance of survival. Outside the ICU, as the family bonded together in grief, other aggrieved people took notice. We were continuously consoled by strangers whom we had never met, all of them offering their moral and financial support. Many women sat with my sisters and mother, offering Quranic verses and prayers for the well-being of my father. On one of my night stays, a stranger brought me dinner and tea. Many others met me and offered their unconditional help whenever required.

This was a world of ‘selfless interest,’ if one may call it like that. Never was there an occasion where anybody could doubt the benevolence of the strangers and their good, selfless intentions. It is hard to explain this behavior through any model. Perhaps death, illness and injury have the power to subdue our selfish nature and bring out the best within us. While self-interest has the power to pit us against each other, selflessness acts as a gravitational force by binding human souls together.

Finally, another interesting observation came at the time of burial. It was my father’s wish to be buried in Islamabad. But as its denizens would testify, it is a prohibitively expensive place where owning a piece of land can be quite a challenge. The same challenge confronts those who wish to bury their loved ones here. As we were grappling with the challenge, a particular law enacted by the Capital Development Authority (CDA) came to our rescue. As per this rule, an owner of a plot in Islamabad is entitled to two graves. Readers may not appreciate the fact how helpful this was in easing the formidable challenge of finding a grave in the capital.

But also notice the clever ploy by the CDA. Knowing well that supply of burial land, at least in the cities, is way shorter than the demand, it incentivized investment in Islamabad through offering graves as complementary good with the investment in land. And investment in land is the lifeline of CDA since it is the biggest source of revenue for the cash-strapped organization. So here again we observe Smith’s classic maxim of self-interest leading to provision of a much needed good. It is not out of benevolence or God’s fear that CDA attached graves as a complement to investing in Islamabad, but rather out of self-interest (the bigger the quantum of such investment, larger the probability to extract a rent under the table). Yet this self-interest, indirectly, provides a needed service.

It is to be noted here that burials are still not free. One still has to pay for the services of preparing a grave and other complementarities, which reflects additional taxes This is a slap on the face of our brain-dead ‘leaders’, who one after the other have made it a habit to call out Pakistanis as tax thieves. Many writers, including yours truly, have been trying to dispel this notion by insisting that we are taxed from birth to death. Is the payment made for graves not a tax?

One gets to witness other interesting phenomenon. For example, the hotels near the hospitals that provide 24-hour service, and tea stalls within the hospital building that sell goods at higher rates than in the market (there are no competitors, at least within the hospital space, and consumers willingly pay to avoid the physical and mental effort of going out). But the above stated should suffice to drive home my assertion about economic activity spinning around death and health misfortune.

I will conclude by suggesting that experiences like illness, disability and death have the ability to bring forth interesting observations regarding human behavior. Our family went through a traumatic experience. But as that experience unfolded, the reality that the world is not so simple was laid amply bare.

The writer is an economist