ظفر:"میں تمہاری طرح کنڈیشنڈ نہیں ہونا چاہتا."

صدیقی: لیکن تم اس طرح کمرے میں مقید جالے کی طرح کب تک لٹکے رہو گے؟

Sarmad Sehbai's plays are Modern Absurdism. His protagonist is a rebel. Very much against his surroundings, socio political environment, injustices and inequalities. Unconventional. Non-conformist. A bohemian who doesn't go with the flow! Be it in following traditional structural techniques of the stage play, or making shades through mixing red colour with yellow by 'Raboo' ( the artist in Hash) who wants to make ‘dirty green’ with the given palette; something unachievable.

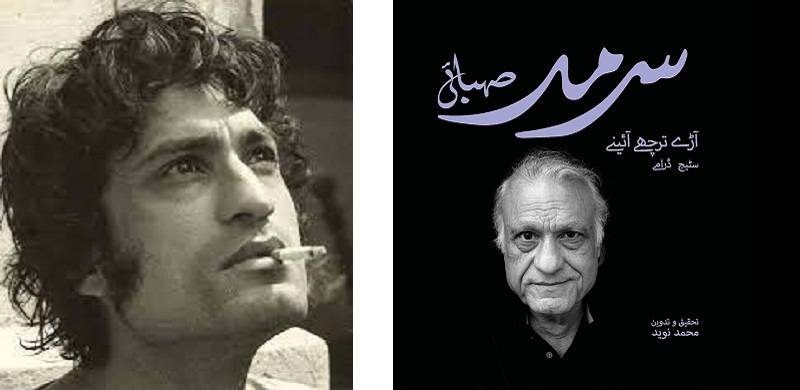

The collection of Sarmad’s plays Aarday Terchay Aeinay published by the Gurmani Center for Languages and Literature at LUMS starts off with the drama Hash, written in late 1968 and performed for the first time in 1973 at the Arts Council Lahore Pakistan (now known as Alhamra Art Council). As the title suggests, it was a mirror showcasing aspects from the more pronounced to the tiniest little itches of the society. Hash was an outcome of a hippie culture where sex and intoxicants were not treated as taboos but highly stylised norms of the then rebellious generation. Hash is pretty much a divine and celestial formula to numb the senses. Here hash does both: provoke and numb. Sarmad Sehbai is a rebel and urges the society to revolt. It is a revolt against the old norms, breaking the chains of a deep-rooted colonial order.

Like Medusa's snake hair, characters struggle against despair and oppression, identifying self. The battle turns out to be self consuming. Birth, death, rebirth are symbolised as Medusa's head, oscillating between suicide and rebellion. Medusa's hair is thus entangled and eating each other in chaos.

Sarmad is an idealist. He invokes ugly conflicts in the social order which have constricted the fresh breath of then and now evolving society as if they were smog. And yet the playwright makes us see and hear the truth. Hash makes the characters bold, thoughtful and bear a zest for a better life, where all are equal without the indulgence of “some are more equal.”

علی: مسئلہ یہ ہے کہ ہارور اسکوپ بھی پولیٹیشنز لکھتے ہیں۔

Sehbai announces rather screams out his idealism in Raboo’s words...

“Let nobody kill my dream!”

Self proclaimed moralists of the bourgeoisie are ridiculed throughout his dramas. Yet, Sarmad doesn't completely attack them. The bourgeois are given space by the playwright by giving them benefit of doubt, like in the character of Saeeda (in Hash).

For Sarmad, following the norms is suicidal.

علی: میں خود کشی نہیں کروں گا ,میں انکار کروں گا, خود کشی کرنے سے انکار ,کتا بننے سے انکار, کموڈیٹی بننے سے انکار ,انکار ,انکار کہ انکار زندگی ہے ،اقرار موت ہے، میں اپنے اندر اور باہر دونوں محاذوں پر جنگ لڑوں گا.

And after a little while, Raboo descends to hopelessness and exclaims he is unable to paint

ربو: علی مجھ سے یہ پینٹنگ کیوں نہیں بنتی ؟کتنے سارے رنگ میری انگلیوں میں تڑپتے ہیں اور پھر ٹھنڈے پڑ جاتے ہیں. میں کئی ہفتوں سے اس پینٹنگ کو وائلنٹ ٹونز دینا چاہتا ہوں لیکن ہر دفعہ میں جب برش پکڑتا ہوں میرا ہاتھ کانپ جاتا ہے اور پھر۔۔۔۔ آخر میں میری تصویر بن جاتی ہے۔ میری اپنی تصویر ،کبڑی بدصورت اور لایعنی بالکل میری طرح ایبسرڈ۔

Sarmad questions the education system. He condemns government services. He is against military oppression, he knows the reality of loans taken from the World Bank and therefore denounces them.

The repartee is Sarmad’s weapon. He sweeps away the whole system of slavery through financing with unmatched wit and brave dialogues.

We come across vaudeville, a technique to vocalise the truth through farcical comical song.

Cynicism is portrayed in his plays. The political allusion of Bhutto's Roti, Kapra and Makaan is vilified. Sarmad questions the irony of such a slogan, as if society needs these three elements to survive, though they are very basic wants without which science and philosophy are far-fetched dreams.

He moves from one religious allusion – Surah Rehman, Surah Yasin and more.

Sarmad’s plays provoke. He is a romantic realist who wants to make things fall in their respective place.

In Ashraf-ul-Makhluqat, the use of colloquial dialogues shows his study of everyday life. Farce satire at its best when “aag laga deini chahiey kitaboon ko!” and “Grilled democracy for rats to eat” are but a few examples of his unrestrained pen.

What amazes the reader more – and must have given goosebumps to the audience during the stage performance – is the pathos flowing through the river of questions.

Sarmad, when he composed these dramas was a young man, probably in his mid-twenties, full of candour, fervour, imagination and enthusiasm. However, his youthfulness doesn't lose track of his intelligence at any point in his writing.

He uses literary allusions from T.S. Eliot and Allama Iqbal. Staying abreast with current affairs, Sarmad knows the art of quilting a drama: weaving the patterns with melodramatic and at times funny and naughty dialogues. He is skilled at bringing out old subjects through treatment of new techniques. It is an approach that results in plays that are full of wisdom.

He paints his characters in true colours of human idiosyncrasies. A pedantic, poor, honest school teacher. A bourgeois burqa-clad wannabe. A deprived wife, sleeping with a gift tightly wrapped in her arms.

Sarmad’s characters were enacted then and now by icons of acting like Sameena Ahmed, Usman Peerzada, Qavi, Talat Hussain and Shakeel (who meticulously and tirelessly performs a soliloquy of 45 minutes, becoming the old man himself in Us Gali na Jawein, the only play with 3 acts written in Punjabi). His work captivates the audience with mesmerising scripts, strong memory skills and acting. Conflict and contrast within the drama is created through the characters and dialogues with the ease of a pro.

Sarmad’s diasporic writings are incoherent with the traditional forms of Aristotelian, Horatian or even that of Shakespearean dramas, with 3- to 5-act plays, rising action, climax, falling action and resolution. He establishes his own culture. Sehbai Sahab lays the foundation of his own technique with two acts. Us Gali na Jawein is the only play with three acts. His prelude could be the climax, with an interlude of lyrics and at times concluding with the speech of protagonist .

Aik Muaziz Shehri ki Rasm-e-Janaza is transgressive and surreal. The stage is divided into three sections and, quiet unlike plays performed in those times, the procession with the coffin walks through the audience towards the stage where the rest of the play is accomplished. It is indeed quite Gothic in perception and execution.

Sarmad Sehbai's plays are vivid visual paintings, which take the reader from one phase to another till the closure comes, where the reader is left:

“[…] To die: To sleep: No More”

صدیقی: لیکن تم اس طرح کمرے میں مقید جالے کی طرح کب تک لٹکے رہو گے؟

Sarmad Sehbai's plays are Modern Absurdism. His protagonist is a rebel. Very much against his surroundings, socio political environment, injustices and inequalities. Unconventional. Non-conformist. A bohemian who doesn't go with the flow! Be it in following traditional structural techniques of the stage play, or making shades through mixing red colour with yellow by 'Raboo' ( the artist in Hash) who wants to make ‘dirty green’ with the given palette; something unachievable.

The collection of Sarmad’s plays Aarday Terchay Aeinay published by the Gurmani Center for Languages and Literature at LUMS starts off with the drama Hash, written in late 1968 and performed for the first time in 1973 at the Arts Council Lahore Pakistan (now known as Alhamra Art Council). As the title suggests, it was a mirror showcasing aspects from the more pronounced to the tiniest little itches of the society. Hash was an outcome of a hippie culture where sex and intoxicants were not treated as taboos but highly stylised norms of the then rebellious generation. Hash is pretty much a divine and celestial formula to numb the senses. Here hash does both: provoke and numb. Sarmad Sehbai is a rebel and urges the society to revolt. It is a revolt against the old norms, breaking the chains of a deep-rooted colonial order.

Like Medusa's snake hair, characters struggle against despair and oppression, identifying self. The battle turns out to be self consuming. Birth, death, rebirth are symbolised as Medusa's head, oscillating between suicide and rebellion. Medusa's hair is thus entangled and eating each other in chaos.

Sarmad is an idealist. He invokes ugly conflicts in the social order which have constricted the fresh breath of then and now evolving society as if they were smog. And yet the playwright makes us see and hear the truth. Hash makes the characters bold, thoughtful and bear a zest for a better life, where all are equal without the indulgence of “some are more equal.”

علی: مسئلہ یہ ہے کہ ہارور اسکوپ بھی پولیٹیشنز لکھتے ہیں۔

Sehbai announces rather screams out his idealism in Raboo’s words...

“Let nobody kill my dream!”

Self proclaimed moralists of the bourgeoisie are ridiculed throughout his dramas. Yet, Sarmad doesn't completely attack them. The bourgeois are given space by the playwright by giving them benefit of doubt, like in the character of Saeeda (in Hash).

For Sarmad, following the norms is suicidal.

علی: میں خود کشی نہیں کروں گا ,میں انکار کروں گا, خود کشی کرنے سے انکار ,کتا بننے سے انکار, کموڈیٹی بننے سے انکار ,انکار ,انکار کہ انکار زندگی ہے ،اقرار موت ہے، میں اپنے اندر اور باہر دونوں محاذوں پر جنگ لڑوں گا.

And after a little while, Raboo descends to hopelessness and exclaims he is unable to paint

ربو: علی مجھ سے یہ پینٹنگ کیوں نہیں بنتی ؟کتنے سارے رنگ میری انگلیوں میں تڑپتے ہیں اور پھر ٹھنڈے پڑ جاتے ہیں. میں کئی ہفتوں سے اس پینٹنگ کو وائلنٹ ٹونز دینا چاہتا ہوں لیکن ہر دفعہ میں جب برش پکڑتا ہوں میرا ہاتھ کانپ جاتا ہے اور پھر۔۔۔۔ آخر میں میری تصویر بن جاتی ہے۔ میری اپنی تصویر ،کبڑی بدصورت اور لایعنی بالکل میری طرح ایبسرڈ۔

Sarmad questions the education system. He condemns government services. He is against military oppression, he knows the reality of loans taken from the World Bank and therefore denounces them.

The repartee is Sarmad’s weapon. He sweeps away the whole system of slavery through financing with unmatched wit and brave dialogues.

We come across vaudeville, a technique to vocalise the truth through farcical comical song.

Cynicism is portrayed in his plays. The political allusion of Bhutto's Roti, Kapra and Makaan is vilified. Sarmad questions the irony of such a slogan, as if society needs these three elements to survive, though they are very basic wants without which science and philosophy are far-fetched dreams.

He moves from one religious allusion – Surah Rehman, Surah Yasin and more.

Sarmad’s plays provoke. He is a romantic realist who wants to make things fall in their respective place.

In Ashraf-ul-Makhluqat, the use of colloquial dialogues shows his study of everyday life. Farce satire at its best when “aag laga deini chahiey kitaboon ko!” and “Grilled democracy for rats to eat” are but a few examples of his unrestrained pen.

What amazes the reader more – and must have given goosebumps to the audience during the stage performance – is the pathos flowing through the river of questions.

Sarmad, when he composed these dramas was a young man, probably in his mid-twenties, full of candour, fervour, imagination and enthusiasm. However, his youthfulness doesn't lose track of his intelligence at any point in his writing.

He uses literary allusions from T.S. Eliot and Allama Iqbal. Staying abreast with current affairs, Sarmad knows the art of quilting a drama: weaving the patterns with melodramatic and at times funny and naughty dialogues. He is skilled at bringing out old subjects through treatment of new techniques. It is an approach that results in plays that are full of wisdom.

He paints his characters in true colours of human idiosyncrasies. A pedantic, poor, honest school teacher. A bourgeois burqa-clad wannabe. A deprived wife, sleeping with a gift tightly wrapped in her arms.

Sarmad’s characters were enacted then and now by icons of acting like Sameena Ahmed, Usman Peerzada, Qavi, Talat Hussain and Shakeel (who meticulously and tirelessly performs a soliloquy of 45 minutes, becoming the old man himself in Us Gali na Jawein, the only play with 3 acts written in Punjabi). His work captivates the audience with mesmerising scripts, strong memory skills and acting. Conflict and contrast within the drama is created through the characters and dialogues with the ease of a pro.

Sarmad’s diasporic writings are incoherent with the traditional forms of Aristotelian, Horatian or even that of Shakespearean dramas, with 3- to 5-act plays, rising action, climax, falling action and resolution. He establishes his own culture. Sehbai Sahab lays the foundation of his own technique with two acts. Us Gali na Jawein is the only play with three acts. His prelude could be the climax, with an interlude of lyrics and at times concluding with the speech of protagonist .

Aik Muaziz Shehri ki Rasm-e-Janaza is transgressive and surreal. The stage is divided into three sections and, quiet unlike plays performed in those times, the procession with the coffin walks through the audience towards the stage where the rest of the play is accomplished. It is indeed quite Gothic in perception and execution.

Sarmad Sehbai's plays are vivid visual paintings, which take the reader from one phase to another till the closure comes, where the reader is left:

“[…] To die: To sleep: No More”